Some Can Channel these Demons Better than Others

Grand Mal can be frantic, it’s often funny, often strung out, yet the craft here never wavers. The poems hang together the way a talented musician knows to assemble dissonant chords, making them something powerful and profound that will move people, provided it’s done without strain or artifice.

What makes Dennis Mahagin run? Run, as in jet engine propelling tons of steel down a runway and up into the sky. From his opening poem, “Grand Mal w/ Grown Up,” it’s clear things are out on the table:

“Back then there was Grandma, / stuffing your thoughtless pie hole / with a freshly-bought / Ivory soap cake, / after you popped off / to your impressionable siblings / at breakfast, a wisecrack / about the sweet / peach ridge panty cleft / on February’s / Sports Illustrated / swimsuit cover model— / . . . ”

Grand Mal can be frantic, it’s often funny, often strung out, yet the craft here never wavers. The poems hang together the way a talented musician knows to assemble dissonant chords, making them something powerful and profound that will move people, provided it’s done without strain or artifice. For many years Mahagin was a bass player and songwriter — no surprise! Music punches up each of his fractured poetic lines, so when they coalesce into lyrical scenes they move and shout and lament from that deep well in the land of the down and out: the almost dead; or dead for all practical purposes.

So why Grand Mal? Medically speaking, a grand mal seizure is characterized by 4 phases (there’s an epigraph — quoted from the Epilepsy Foundation of America– explaining each Phase, as it delineates the book’s 4 sections).

Mahagin writes in “Banishing the Snakes”:

“It’s a go-fast world, and green / is the color of my disease— / . . . / I’ve done that / Riverdance sidestep, / caught the flak of dripping fang / that makes you so dreadful sick; / and I can tell you: no driftwood / wishbone stabbing stick at arms length / will work on this bitch it’s strictly up / close and personal, under your thumb / in a fire nozzle grip, until she opens wide, / blasting poison like syphilis piss / on a slush bank . . .” (from Phase 1).

Sub-dividing the book in this way allows the poems a forward momentum that tightens narrative tension, while at the same time maintaining the seizure as its driving metaphor. He writes in “Fare”:

“The Laotian impresario / at the outcall agency / recommended her / as a star in his stable: / “She go slow— she so / con-sooo-mate . . . pro.” / Now, as she slips on / the glistening condom / with her mouth / in a frisson of python, he bats back / the eyelid splash of rushing purple dusk / . . . ” (from Phase 2).

So what makes Mahagin run? Perhaps the demons of his past, present, and the always uncertain future, which is part and parcel of what makes poetry such a compelling art form. Some can channel these demons better than others. Mahagin puts it transparently out there, saying to anyone who happens to amble by, for a read:

“Stuff they give / to empty you / out, / makes sleep / tough, / getting up / to go, crapper / to sack , and back / . . . ” from “Endoscopy” (Phase 4).

Grand Mal is the second book by this prolific poet. I eagerly anticipate more. What makes Dennis Mahagin run? Run, as in jet engine propelling tons of steel down a runway and up into the sky. From his opening poem, “Grand Mal w/ Grown Up,” it’s clear things are out on the table:

“Back then there was Grandma, / stuffing your thoughtless pie hole / with a freshly-bought / Ivory soap cake, / after you popped off / to your impressionable siblings / at breakfast, a wisecrack / about the sweet / peach ridge panty cleft / on February’s / Sports Illustrated / swimsuit cover model— / . . . ”

Grand Mal can be frantic, it’s often funny, often strung out, yet the craft here never wavers. The poems hang together the way a talented musician knows to assemble dissonant chords, making them something powerful and profound that will move people, provided it’s done without strain or artifice. For many years Mahagin was a bass player and songwriter — no surprise! Music punches up each of his fractured poetic lines, so when they coalesce into lyrical scenes they move and shout and lament from that deep well in the land of the down and out: the almost dead; or dead for all practical purposes.

So why Grand Mal? Medically speaking, a grand mal seizure is characterized by 4 phases (there’s an epigraph — quoted from the Epilepsy Foundation of America– explaining each Phase, as it delineates the book’s 4 sections).

Mahagin writes in “Banishing the Snakes”:

“It’s a go-fast world, and green / is the color of my disease— / . . . / I’ve done that / Riverdance sidestep, / caught the flak of dripping fang / that makes you so dreadful sick; / and I can tell you: no driftwood / wishbone stabbing stick at arms length / will work on this bitch it’s strictly up / close and personal, under your thumb / in a fire nozzle grip, until she opens wide, / blasting poison like syphilis piss / on a slush bank . . .” (from Phase 1).

Sub-dividing the book in this way allows the poems a forward momentum that tightens narrative tension, while at the same time maintaining the seizure as its driving metaphor. He writes in “Fare”:

“The Laotian impresario / at the outcall agency / recommended her / as a star in his stable: / “She go slow— she so / con-sooo-mate . . . pro.” / Now, as she slips on / the glistening condom / with her mouth / in a frisson of python, he bats back / the eyelid splash of rushing purple dusk / . . . ” (from Phase 2).

So what makes Mahagin run? Perhaps the demons of his past, present, and the always uncertain future, which is part and parcel of what makes poetry such a compelling art form. Some can channel these demons better than others. Mahagin puts it transparently out there, saying to anyone who happens to amble by, for a read:

“Stuff they give / to empty you / out, / makes sleep / tough, / getting up / to go, crapper / to sack , and back / . . . ” from “Endoscopy” (Phase 4).

Grand Mal is the second book by this prolific poet. I eagerly anticipate more.

Jean-Luc Nancy's The Fall of Sleep: A Paraphrase

1. The nature of the fall particular to the fall of sleep (“I am falling asleep”) is a gathering loosening, the feeling of the loosening of feeling, the falling away of the fall. Sleep is the force that leads us into sleep. It does not transform us (“metamorphosis”), but rather it opens a space within us (“endomorphosis”), an interiority which we recognize by way of our falling into it.

1. The nature of the fall particular to the fall of sleep (“I am falling asleep”) is a gathering loosening, the feeling of the loosening of feeling, the falling away of the fall. Sleep is the force that leads us into sleep. It does not transform us (“metamorphosis”), but rather it opens a space within us (“endomorphosis”), an interiority which we recognize by way of our falling into it.

2. In sleep, the boundary between self and world has faded: it is not I that sleeps, but rather something other that slips into and perfectly fits the mold of I. Night has fallen outside, perhaps; unmistakably it has fallen within the sleeper, for he has become indistinct to himself. The second fall of sleep: a fall of distinctions. The sleeper’s eyes roll back, his outward gaze peers inward.

3. The thing apart from its appearance, Kant’s thing-in-itself, is the condition of the sleeping self. When awake, I am myself; when asleep, I am oneself.

4. Sleep suspends the passion of exhausted lovers, their ardor momentarily — rapturously — forgotten. To sleep together is to sleep with all sleepers, is to sleep with the sleeping world. The difference (light) of day and the indifference (darkness) of night. Night obliterates the shadow of the sundial. The indifference (equality) of sleep.

5. Day as surface, night as substance. The sleep of God differentiated the second day from the first. The ex nihilo of the fiat lux — the dark nothing eclipsed by light — is inherited by sleep. An impossibly complex cinematographic machinery of dream and its own imminent fall. The dreamer who wonders whether he is dreaming, his is an awareness with no object.

6. The rhythm of falling asleep mimics the rhythm of sleep (biological) in accordance with the rhythm of night (cosmic). One must trust in sleep (“one puts mistrust to sleep”), in its guidance toward nowhere, in order to be lulled to sleep. Being rocked to sleep is a rocking between something and nothing, the same rocking of all the world’s symmetries.

7. No sleep for the soul. The soul is itself the rhythm of sleep.

8. Death, a sleep without waking, without waiting. If a dead man could talk, he would say that he is sleeping; he would say, as would all sleepers, that he has joined eternity. Death: the rhythm of the infinite enters the finite. Death: when thought finally falls asleep.

9. The sleeper who fears sleeping, who fears abandoning his fear to sleep. The vision immediately preceding sleep is that of the absence of vision — the horror of this vision may pursue the sleeper as he descends into sleep. To sleep is to see seeing itself, is to see the other side of seeing and sojourn there.

Are You Brave Enough to Call the Body An Activism?

Are you curious, do you have longing, are you ready to open yourself, to be the confidante we in my Trans by j/j hastain asks you to be?

Are you strong enough to let go of your internalized ideation of gender, form, identity, and sexuality? Are you willing to become a provocation or become provoked by the pages of this book? Are you curious, do you have longing, are you ready to open yourself, to be the confidante we in my Trans by j/j hastain asks you to be?

Put aside for a moment any preconceived enculterated notions of the word ‘Trans’ because the use of that word here is different than historicized uses of it. Instead, let go and travel with this writer into the world of a ‘’third city” where fulfillment is based in / from / toward a fulfillment through fucking.

I am talking about fucking as “merge,” as entry into the space of the beloved. This place where the primordial particles of the corporeal coalesce into a relentless ritual, a making holy of bodies, deeply in tune with their own pleasures, needs, desires and fullness, regardless of the manifesting shape or form.

In we in my Trans it’s not just the bodies, or form or fucking, that give this book its energy. It’s the enactment of a spaciousness that allows for all possibilities as in, “this is the act of craving” and “that the force of you in me / is the only thing that will bring my body to an openness / that is capable of knowing / human joy.”

This book of poems / ceremonies / erotics and love embodies the mythos of j/j hastain’s ritual city. It is a book about suture; the way reader, writer, and other intertwine. we in my Trans contains a relentlessness in de-defining a vessel (the body) of applied pressures. Pressures that require disassembling, (“wherein you affirm that you are in me / for always”) gestation, form / formlessness and “as an image / we are / continually reborning” exist simultaneously in the erotic urge of hastain’s language.

I find power here, we in my Trans, is at once, “sensory portraiture / with its infinitely multiplying mysticisms” and also, an homage to the self discovering itself through / in another. I ache as a reader, wanting to find myself in the text, undone by words.

This is the essence of the “merge,” the coming together, in order to create an entirely new thing, “how two or more / in effort at harmony / will always make a harmonic.”

hastain is unabashed and honest about the ways sexuality / identity / gender and love become a chimera of myth and undulating text. The photos in the book are at once a punctuation and a window. There is no doubt that you are on a journey through a new type of landscape, with strange almost familiar shapes. You don’t expect to find rest in them and they serve as an extension of the text in its invocation to desire.

It’s a vulnerable subtlety to be involved in so intimate a text. At times, you may ask yourself if you are turned on, or if you’ve become a voyeur. You may ask yourself where you end and the page begins. as I did. Whatever the answer, you will sleep with this book next to your bed and wake up dreaming it.

Michael Leong's Philosophy of Decomposition/Re-composition as Explanation

Leong’s poetry works well with the book art, and let’s face it, the book art really has the potential to overshadow the words it’s holding together. But instead, the design really compliments the book’s subject, “a mash-up/re-mix/collage of Poe’s The Philosophy of Composition and Stein’s Composition as Explanation.

Last summer, right before Crane Giamo and Kelley Irmen left Fort Collins, CO for Tuscaloosa, Alabama, Daniel Bailey and I went to their house to say goodbye and take their pictures. They had sold everything, so we didn’t have much to do but sit out on the landing right outside their doorway and watch Crane light things on fire.

Crane made his own gunpowder. Out of his own urine. And he showed us these wild designs he could make on paper if he sprinkled a little powder and lit it with a spark. He gave me an envelope full of charred willow sticks (amazing for drawing and also made in someone’s backyard) and he and Dan burned holes in paper. Man, I miss you guys.

A few months later, Dan and I got a copy of The Philosophy of Decomposition / Recomposition as Explanation: A Poe and STein Mash Up by Michael Leong. Each copy was handmade by Crane, laid out by Jared Schickling. And each copy features an original piece of gunpowder artwork. It’s an experience just to hold these in your hands.

Leong’s poetry works well with the book art, and let’s face it, the book art really has the potential to overshadow the words it’s holding together. But instead, the design really compliments the book’s subject, “a mash-up/re-mix/collage of Poe’s The Philosophy of Composition and Stein’s Composition as Explanation.

I hadn’t read either of these two works so I don’t know that I would have picked this up without a recommendation. And this long poem is heady, there’s no getting around that. I mean it’s not a beach read, it’s not something I would bring to an airport. It’s more for keeping around when you need to have a think about something. Like after you’ve been watching The Wonder Years for like, 3 hours straight and want to feel your brain work again. It’s smart and beautiful and yes, at times difficult to wrap your head around but we all need that sometimes, don’t we?

I want to also talk about Delete Press’s work in general, because we were lucky to receive with The Philosophy of . . . a box Crane had made as a literal vessel for poetry. It was so cool to have a tactile piece of work — something that connects reading to seeing to experiencing. Have ya’ll read Anne Carson’s Nox? Dan brought it home from a class last year. That is a beautiful box of words and collage. It’s cumbersome and it’s not easily digestible and you have to work at it. It’s extraordinary.

Delete Press’s limited edition chapbooks do that, too. The founders of Delete Press (Crane, Jared, and Brad Vogler) are concerned with making beautiful books. Otherwise, they’d print out more than 90 or 70 or 17 copies of a work. There’s just something so fascinating to me about a press that is willing to put that kind of effort into every single book (and not charge an arm and a leg for that kind of exclusivity, either).

As someone who works online, professionally (basically a professional internet user), I find myself increasingly interested in the limited, the tacticle, the things that take time and patience. Letter writing. Photocopying ‘Zines. Collaging with scissors instead of photoshop. It lets my eyeballs do less work when my other senses are busy working, too. So while I’m the first to admit that I wouldn’t necessarily pick up a pee powder burn book (literally, you guys), I’m glad that I know the founders and am thus forced to pick up their books. These guys are talented, and they work with incredibly smart writers. They inspire me to keep creating, and they prove that poetry can be experienced beyond words.

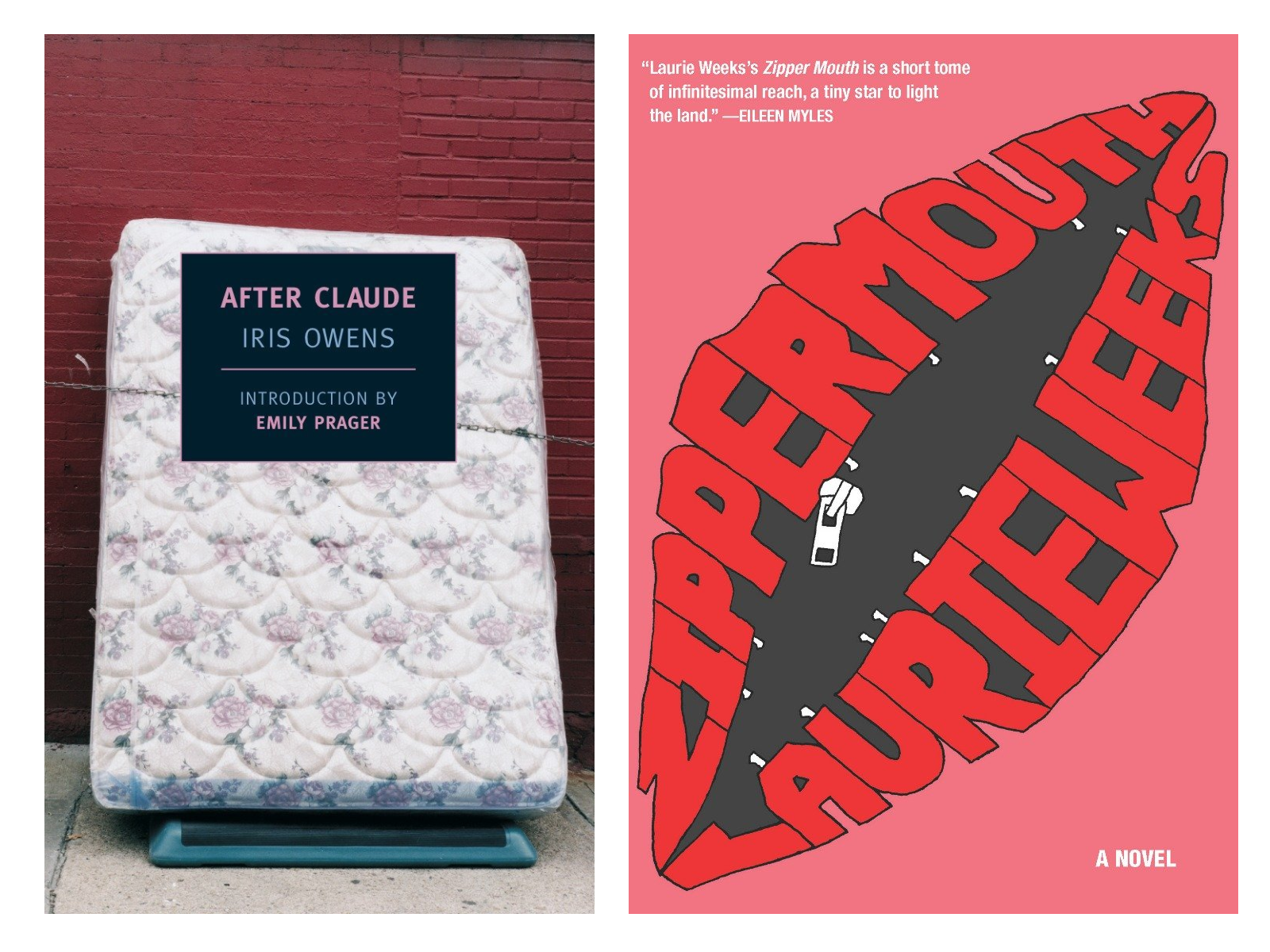

After Claude by Iris Owens and Zipper Mouth by Laurie Weeks

I’m going to cheat and recommend two books, even though I was asked to recommend only one. I’m cheating in part because I can’t decide, and in part because I think these two books are interesting when read together, or remembered together, or placed side by side.

I’m going to cheat and recommend two books, even though I was asked to recommend only one. I’m cheating in part because I can’t decide, and in part because I think these two books are interesting when read together, or remembered together, or placed side by side. Or so they have sat on my mental bookshelf for the past several months. The first is After Claude by Iris Owens, which was first published in 1973, and which was republished by the New York Review of Books in 2010; the second is Zipper Mouth by Laurie Weeks, published in 2011 by the Feminist Press, under the excellent editorial direction of Amy Scholder.

I’m embarrassed to say that I didn’t know anything about Iris Owens until I read a 2011 review of After Claude in Bookforum, in which Gerald Howard describes the book as a masterpiece of female abasement, “a foulmouthed comic tour de force, still capable of offending the offendable and casting a blue-streaked spell of hilarity over everyone else.” I bought it right away to see if I agreed; I did. Weeks, on the other hand, I’ve known for years — I was in fact one of the many anxiously awaiting the publication of any tidbit that could be excised from the obviously brilliant fog of writing that has hovered around her, albeit without any book-length publication, for decades.

Both of these books are drug-addled, downtown New York City abjection narratives with utterly fierce and hilarious first-person narrators, one hailing from the 70s (Owens), the other from the Now (Weeks). Both books are as memorable and caustic as they are slender and rare. By “slender” I mean they both clock in around or under 200 pages, and are compulsively readable in a single sitting; by “rare” I mean that both Owens (who died in 2008) and Weeks (who is alive) have published very little in light of the largesse of their reputations and talents. (This isn’t entirely true in Owens’s case, as she wrote quite a bit of porn as “Harriet Daimler,” but as Howard puts it in Bookforum, “As Harriet Daimler, [Owens] was alarmingly prolific; as Iris Owens she was a dry well. [Stephen] Koch cited to me her ‘capacity for procrastination, indolence, and inaction beyond anything I’ve ever seen in someone so gifted.’” I don’t know enough to say the same of Weeks exactly, and I can’t presume, but it seems that something of the sort is also at hand, which makes the publication of Zipper Mouth a cause for celebration.

So those are the similarities. Beyond that, the books are very different. Owens’s narrator (who is named Harriet, of all things) is utterly awful — self-loathing and loathing of all others — and does horrible things, like surprising a friend by planting a strange, naked man she’s found in a single’s ad in her friend’s bed to “liberate” her, or changing the locks on the apartment of the titular Claude, whose apartment she has refused to leave. Owens gives us keen, often riotous metaphors for how shitty all the drugs, alcohol, rejection, and abjection make Harriet feel, but beyond that invention, After Claude is decidedly sublunary, rooted in the endless, despicable present. Zipper Mouth, on the other hand, is hallucinatory and roving, allowing for dreams, specters, epistolary interludes, lyric and temporal vaulting. Perhaps the biggest difference is that Weeks’s narrator is a romantic rather than a cynic, and remains completely enthralled to desire — most notably, for beautiful, taunting, straight girl Jane, and when Jane can’t be had, for dope. Weeks’s narrator is essentially defined — like the subject of Roland Barthes’s A Lover’s Discourse— as the one who loves. As a result, there’s a kaleidoscopic longing and poetic range in Zipper Mouth — not to mention a welcome queerness — that After Claude decidedly does not have.

That said, I find both books quite moving, albeit in distinct ways. As some have disapprovingly noted, After Claude reads like two different books—first, the story of Harriet and Claude; then of Harriet’s post-Claude trip to the Chelsea Hotel, where she has a nightmarish run-in with a 70s guru / hippie / creep / cult-y guy who wheedles her into masturbating on (audio) tape, which he then plans to bring back some gross archive he keeps at his harem-cum-Waco outpost. The conclusion of the book finds Harriet totally distraught, as she really did relax and come in the guy’s presence with an unusual vulnerability. The novel’s last line, “I opened a fresh pack of Marlboros and stared at the brown and white circles. I had no thoughts, only a dim awareness of myself listening and waiting,” is haunting. Weeks’s book also has a defiantly non-happy (though beautiful, rushing) ending: “The sun she is gorgeous but the golden tresses of her rays are tumbling into the abyss and are lost.” As witty, likeable, and compelling as Weeks’s narrator is, she isn’t ever going to get the girl, and dope will keep winning its mean game. The past (which involves wincing flashbacks of an alcoholic father) will keep pulsing with trauma; the present will stay alive with a crackling but cyclical pathos (as in the scene in which the narrator ends up bringing home a paranoid homeless junkie she once gave $5 to at the ATM; an interminable night of drugs, vomiting, showering, and insane conversation follows, making for one of the best scenes in the book).

The triumph of both books lies in their language, their sentences, their figures of speech, their unrivaled humor, and their anarchic and wild sound of women taking no prisoners—a still underheard and underrated sound in fiction, as in life. As far as drug memoirs go, either of these two books holds more interest for me than all the On the Roads and Cain’s Books out there. For instead of producing a weary fatigue, that here-we-go-againfeeling I get when faced with an existentially burdened, drug addicted, misogynist male character or writer being made heroic by literary sleight of hand, or by the still rabidly (if unconsciously) sexist forces that create and perpetuate literary history, these two heroines and their creators make me feel endless interest, radical discomfort, a profound sense of accompaniment and recognition, and a totally necessary sense of artistic permission and possibility. Maybe you will feel the same, I don’t know. Read them tonight.

An Interview with Lydia Millet

I met Lydia Millet in 2009, in a writing workshop at the University of Alabama. I remember grabbing a beer and talking about graphic novels and Friday Night Lights at our local pub, about having children and a job and still finding time to write, and about how nice it was to get away for a weekend. I didn’t even know she liked animals — until I picked up the first book of a trilogy she’s currently working on.

I met Lydia Millet in 2009, in a writing workshop at the University of Alabama. I remember grabbing a beer and talking about graphic novels and Friday Night Lights at our local pub, about having children and a job and still finding time to write, and about how nice it was to get away for a weekend. I didn’t even know she liked animals — until I picked up the first book of a trilogy she’s currently working on.

Lydia Millet is the author of many novels as well as a story collection called Love in Infant Monkeys (2009), which was one of three fiction finalists for the Pulitzer Prize. 2011 saw the publication by W.W. Norton of a novel called Ghost Lights, named a New York Times Notable Book, as well as Millet’s first book for middle readers, called The Fires Beneath the Sea. Millet works as an editor and writer at a nonprofit in Tucson, Arizona, where she lives with her two small children.

* * *

Megan Paonessa: First off, how do you like being compared to Kurt Vonnegut on the cover of How the Dead Dream? I like Vonnegut, don’t get me wrong (he’s a Hoosier!), but that sort of blurb obviously colors expectations — and one can’t help but judge a book by its cover.

Lydia Millet: I’m always a bit perplexed by that comparison, owing to the fact that I haven’t read Vonnegut since my teens. Clearly I need some reeducation. In general though, comparisons to other writers are simultaneously flattering and insulting. I don’t know why it’s so necessary to go the Hollywood pitch route to describe literary books. “It’s Writer Brand X crossed with Writer Brand Y.” If I’m doing my job it’s not X crossed with Y at all.

MP: How do you feel about stereotypes? The IRS man. The real estate man. The office affair. The gay Air Force man. The breast-obsessed business types. These are all stereotypical character traits found in your novels, but as I found myself identifying them, I still thought these characters were uniquely interesting.

LM: I love stereotypes — types in general. I’m guessing that’s pretty clear. They are fascinating. Hey, stereotypes don’t kill people. Bad writing kills people.

MP: True! I guess what I’m trying to ask is, do you use stereotypes in order to say something . . . broader (?) . . . about life, the world, people? You mentioned in an interview with Willow Springs that one of the things you react against is the preoccupation with the personal in contemporary literary fiction.

LM: Well stereotypes are mostly just obvious objectifications of people, right? Partly I want to objectify fictional people because it’s funny; partly I want to objectify them because I like to play with distance — the distance between the reader and the characters, the narrator and the characters, the author and the characters.

MP: Many of your reviewers describe your writing as deeply satirical. How important to you is the insertion of a political / ecological / moral / social stance?

LM: All this talk of insertion! It sounds rude. I don’t think of inserting things.

Not all my writing has a satirical tone. The trilogy of novels doesn’t, for example. But I can never leave the comic aside for too long.

MP: What do you mean by the comic?

LM: The comedic. I always end up returning to what’s funny to me, whether it’s marginal in a book or central. So while I don’t know that my most recently published books are particularly satirical, I do have a book I’m working on that’s more so, if only because I need to get away from the heavy sometimes.

MP: Writing drama carries the hazard of falling into melodrama — as Hal points out at the end of Ghost Lights. From what I’ve read about your work, Hal’s sort of soul pouring wasn’t always common in your characters. Was this trait specific to Hal, or has your writing been influenced in a new direction?

LM: Well, I don’t know that it’s not common — I’ve always been a sucker for internal monologue and so I think there’s a fair amount of soul pouring throughout my books. Ghost Lights is less a new direction than How the Dead Dream was.

MP: Do you think there’s a move in contemporary literary fiction to steer clear of emotional narratives?

LM: I think the pretense that writing without emotion can exist is funny. You don’t want to go the direction of maudlin, you don’t want to overwrite, but underwriting emotion is a bore too, finally — safe and easy.

MP: So there has to be a balance.

LM: I wouldn’t say balance. Balance implies equilibrium, and I’m not sure how helpful that is in fiction. But I’d say emotion and cerebration are both important and compelling, and either without the other is a bit dull to me.

MP: Lastly, can you give us a glimpse into the last book of the trilogy? Perhaps (!!) which character’s point of view the narration will come through?

LM: My pleasure! The last book will come out next fall from Norton, it’s called Magnificence, and it’s written from the perspective of Susan, Hal’s wife. She inherits a house full of taxidermy in Pasadena.

MP: Taxidermy? Fantastic. I wonder how T. will react to that. I can’t wait to read it! Thanks, Lydia.

I'd Love A Tour Inside Nick Antosca's Head, But I'd Hate to Spend the Night: A Review of Fires

That was my first thought after reading Fires, Antosca’s debut novel — an impression very much reinforced by his second book, Midnight Picnic. But then again, if you’ve read one book by an author let alone two, you’ve pretty much camped out in his head. And this is especially true of Antosca, whose writing feels incredibly personal. It’s this intimacy — more than the darkness of the subject matter — that makes the dread permeating his books so immediate and palpable.

That was my first thought after reading Fires, Antosca’s debut novel — an impression very much reinforced by his second book, Midnight Picnic. But then again, if you’ve read one book by an author let alone two, you’ve pretty much camped out in his head. And this is especially true of Antosca, whose writing feels incredibly personal. It’s this intimacy — more than the darkness of the subject matter — that makes the dread permeating his books so immediate and palpable.

Fires was originally published by Impetus Press which, like the rest of the publishing industry, pretty much imploded. It has since been re-released by Civil Coping Mechanisms. This new package includes a snazzy new cover (NOW IN COLOR!) and three bonus stories: “Rat Beast” is hilarious; “Winter was Hard” and “The Girlfriend Game” really are not.

I love the trajectory of Fires. It opens depicting the relationship between two college students, setting up the framework for a coming-of-age narrative, and then it takes a surprising and very dark detour through a concealed room and ends with a solitary figure reclining on a bed in a burning neighborhood. Whenever I read a novel and I think I know where it’s going, I imagine an ending where the main characters kiss against a backdrop of fire. Antosca . . . actually goes there. But he establishes such a solid foundation that the ending — which could easily devolve into pure vaudeville — is both tragic and inevitable.

Regarding that foundation, look at the way Antosca, in the first few pages, takes us through the romance between two undergraduates. To be reductive: boy meets girl, girl has a cold, and during a romantic but ultimately chaste tryst, girl gives the cold to boy. I’ve never encountered a fictional romance where the couple literally infects each other during their meet cute. And it’s a moment that both captures the idealism of young romance — the boy is so enamored with the girl he’ll cuddle with her despite her flaming disease — and is also utterly disgusting.

Antosca’s characters might be unhinged, but they’re all so engaging that when they get involved with each other, we want to be involved with them as well. And when their relationships take them to some very dark places, well, they lure us down with them.