In Slot's New Book, Poetry Becomes Both An Homage To Tradition And An Intervention

Andrea Witzke Slot’s finely crafted first book echoes with the voices of writers past and present. H.D., David Baker, and John Keats are only a few of the poets whose work informs this refreshingly well-read debut. With that in mind, Slot’s poems raise compelling questions about the role of the individual in an established literary tradition: If poetry is a conversation, how does one define originality? Does it exist only as variation, refinement of what’s been written before? To what extent does homage blur into destruction?

Andrea Witzke Slot’s finely crafted first book echoes with the voices of writers past and present. H.D., David Baker, and John Keats are only a few of the poets whose work informs this refreshingly well-read debut. With that in mind, Slot’s poems raise compelling questions about the role of the individual in an established literary tradition: If poetry is a conversation, how does one define originality? Does it exist only as variation, refinement of what’s been written before? To what extent does homage blur into destruction? As Slot teases out possible answers, her haunted and haunting poems allow myriad literary influences to coexist gracefully in the same narrative space.

Slot’s treatment of her Modernist predecessors proves to be especially fascinating as the book unfolds. Frequently drawing attention to female figures whose work has escaped the widespread recognition seen by such male writers as Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, and James Joyce, Slot suggests that poetry may redirect the focus of our discussions of literary tradition. In many ways, poetry affords the opportunity to revise the cannon, redefining its terms to suit a changing cultural landscape. In Slot’s new book, poetry becomes both an homage to tradition and an intervention. It is this blend of reverence and destruction that makes her work so intriguing. Consider “Hawks Nest, St. John, USVI,”

The hills tongue their way to sea

as if the sea begs the land to slide

into its waiting, open mouth.

The slick blue mirror

is deceiving… (13)

Here Slot appropriates numerous tropes of Imagist poetry. The poetic image becomes a point of entry to complex philosophical and emotional questions, which it is the reader’s job to unravel. In many ways, the structure of the book is especially significant. By prefacing this poem with a line from H.D.’s “Sea Gods,” and placing this piece at the front of the collection, Slot jostles the hierarchies that have been imposed upon the literary cannon. Likewise, the placement of the stylistic tropes associated with Imagism at the forefront of the collection suggests their largely overlooked influence on contemporary poetry.

With that said, Slot’s use of epigraphs to comment on prevailing interpretations of the cannon is equally impressive. Frequently excavating overlooked gems—a phrase, an image, a metaphor—Slot cautions us against becoming entangled in the sweeping manifestoes and ambitious claims that populate literary history. Rather, she highlights the value of the smallest, but often most dazzling, accomplishments of her predecessors. It is these modest masterpieces that provide some of the most valuable material for contemporary poets. She writes in “Ode to a Bear: Part I,”

That night we slept curled in one sleeping bag.

I dreamt of Ben, saw Boon’s knife slash his throat.

Lion was ripped to shreds. But in this dream

the bear did not die; he moved to the forest’s edge

and turned to stare with yellowed eyes. In fear,

I clung to you—and realized why you brought me here. (17)

Prefaced by a quotation from Faulkner, this poem is fascinating in that it presents the landscapes of his novels through the eyes of a female protagonist. The epigraph is effective in situating the poem within an existing literary tradition, which the text proceeds to revise, adapting Faulkner’s aesthetic to a rapidly shifting social terrain. Slot’s epigraphs frequently exist at the intersection of homage and revision. But this is what makes her work so fascinating. She envisions literary tradition as being constantly in flux, a work in progress that is always subject to revision.

For Slot, the past does not limit us, but rather, serves as the starting point for one’s own contribution to an artistic conversation. Appropriation, reinvention, and dialogue afford exciting possibilities, which are not available to those working outside of an established literary tradition. It is her liberal approach to this received source material that renders her work so rich from an interpretational standpoint. With that in mind, the poems in this collection lend themselves to careful attention, and reward re-reading. To find a new beauty is a book that’s as well-read as it is engaging. This is a wonderful debut from a talented poet.

A Tap On My Shoulder

As soon as I got to the performance space, though, I saw that Women of Letters was going to be positively elegant. It was at Joe’s Public in Manhattan: opulent terraced seating, soft banquettes illuminated by candlelight, and servers as languid and chilly as mermaids.

I confess that I expected ‘Women of Letters’ to be a scrappy affair held together with enthusiasm and string, because, since both women and the written word are so undervalued, the combination can tend to the homemade. But words and women are also my two favorite things, so off I went. As soon as I got to the performance space, though, I saw that Women of Letters was going to be positively elegant. It was at Joe’s Public in Manhattan: opulent terraced seating, soft banquettes illuminated by candlelight, and servers as languid and chilly as mermaids.

Originated five years ago by co-creators Marieke Hardy and Michaela McGuire, and hosted by the gracious Sofija Stefanovic, Women of Letters’s raison d’etre is to encourage the fading (please let’s not call it lost just yet) art of writing letters. The format is simple, six guests invited to write on a theme, who read their result onstage. This evening’s theme was “A Tap on My Shoulder.”

Beth Hoyt, who acts in and writes for Inside Amy Schumer and co-hosts the comedy show Big Effing Deal, kicked off the letters with the phrase, “Dear Dude.” The dude in question was a stadium-goer at the first Michigan State football game to take place after 9/11 — a man who pierced the highly protracted and reflective silence after the National Anthem by shouting,“boobies!” Piloting narrative hairpin turns with brio and irreverence, Hoyt pulled together tales of economic disparity, Gwyneth Paltrow, and the impossibility of ever saying the right thing into one salty whole, funny as hell.

The sparky tone turned glowy as Anna Holmes, journalist and the founder of Jezebel, read an intimate essay that inquired whether ignoring one’s instincts might be a gendered act. With precision and generosity, Holmes described her aha moment: the realization that constant self-critique is not the same as personal awareness. “The essential mistrust of self exacted a steep personal price.” She spoke of her father’s stories of himself as a young black man — how crucial to his survival had been his ability to sense what he could, and couldn’t, do. “His instincts had served him well,” Holmes concluded, “and they’d serve me well, too, if I’d only fucking listen.”

“Dear Tap,” began Amy Sohn, screenwriter and author of The Actress and Prospect Park West, “I know you want me to pull my head out of my ass, but I’m not ready to get it out of there yet.” Thus began a tragicomic tour de force worthy of Dorothy Parker at the top of her game, getting progressively darker and funnier at each turn until the audience was screaming with horrified laughter.

Sigrid Nunez had exactly the august bearing one might associate with a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences as she began a letter to her mother, a coming-of-age story that detailed the moment of individuation between mother and daughter. With deft knowingness, Nunez’s prose, profound yet effervescent, captured essential, monumental issues as though scooping up butterflies in a net. When Chekov’s gun went off – by which point we’d all forgotten it was ever on the mantelpiece to begin with – it brought the house down.

The presence of Megan Abbott, doyenne of noir and author of I Dare You and The Fever, is somehow simultaneously winsome and mysterious, and her letter was too: a sinuous, twisty search for escape from the pain of separation, making fleeting, meaningful contact with pleasure while propelled along by an increasingly frantic desire for escape. It was sharp and heartachey, shot through with weird sweetness.

Molly Crabapple is an artist and journalist who’s done projects in Guantanamo Bay, Abu Dhabi’s migrant labor camps, and with rebels in Syria; her work is in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art. Those of us who were comparing our own CV to hers found it encouraging that she addressed her letter to her burnout. It told of her path as an artist, starting as a punk so obsessed with drawing she’d do it until her tendons seized, “punching them until they could curl around a pen again.” She spoke of work functioning as an addiction, until her ability to work deserted her, while burnout stuck around. Of being a journalist, she said, “I had to learn to tell the truth in a world populated entirely by liars – but that wasn’t burnout, that was burned in.”

A panel discussion followed, which is typically when everybody starts shifting in their seats. Not so under Stefanovic’s supple touch. To the first question – about memorable fan mail – Megan Abbott quickly supplied, “Yeah, a woman wrote to me saying ‘I wrote that book you published, and it was weird to see your photo on the book jacket.’” Amy Sohn’s response was so raunchy I can’t, or anyhow won’t, relate it here. Stefanovich asked if anyone had letters they can’t look at — everyone did. (Holmes spoke of “performative” missives written in college). For a recent project, Crabapple had been dispatched to read her own diaries and fact-check her past. “My self-mythologizing bubble burst,” she said. Sohn posed the question: why don’t people throw away letters that reveal secrets? Crabapple, who spent years in correspondence with Guantanamo Bay detainees, pointed out that prisoners are who’s keeping the form alive.

Fortunately there are others in the world who value the form too, and Women of Letters certainly walks the walk: to conclude the evening, Stefanovic directed our attention to the stamped postcard on each table. “Write to someone you love,” she told us. “Everybody’s always happy to get a letter. Go write on your postcard, and mail it. Give them that gift!”

I wrote mine to my sister. Thinking of you, love you. A few days later, I got an email in return. The postcard had arrived on a difficult day; she’d come home and wept, and then read it. Getting that postcard was exactly what I needed, she wrote.

Women of Letters returned to Joe’s Public on June 10th.

Intractable Ghosts or Kristina Marie Darling’s Personal and Imaginative World in The Sun & the Moon

Sometimes an extraordinary book lands on your doorstep and you’re grateful to be astonished again. Kristina Maria Darling’s The Sun & the Moon is a beauty to behold. A surprising, masterfully written long prose poem that reads like a novel, it weaves a story of a marriage deconstructed in a fantastical, surreal setting, whose strangeness is reminiscent of Edgar Allan Poe: “I tore into the envelope & there was only winter inside, not even a card or a handwritten note.”

Sometimes an extraordinary book lands on your doorstep and you’re grateful to be astonished again. Kristina Maria Darling’s The Sun & the Moon is a beauty to behold. A surprising, masterfully written long prose poem that reads like a novel, it weaves a story of a marriage deconstructed in a fantastical, surreal setting, whose strangeness is reminiscent of Edgar Allan Poe: “I tore into the envelope & there was only winter inside, not even a card or a handwritten note.”

We’re invited into a mysterious, hypnotic, universe unfolding like a party: “You began as a small mark on the horizon. Then night & its endless train of ghosts. You led them in, one after the other. They took off their shoes, hung their coats & started looking through the drawers.” The reader can only fall in love with the ingenious writing as she/he falls under the spell of this haunted love story that reads like a long dream sequence.

Both modern and timeless, it echoes into past centuries, with eerie references to bouquets, lockets, and love notes: “I became aware of your voice calling me from the stairs, warning me about the silver lock on the door.” It reminded me of The Turn of the Screw, by Henry James, with its tight writing, suspense, and destruction. Inhabited by ghosts, disquieting, The Sun & the Moon compels the reader to sort out the living from the dead:

“One by one the ghosts left for the ocean, dragging the cold dark stairs behind them.”

“You just stand there & stare, your suit covered in ash, the altar catching fire behind you.”

“Still you just stand there, light shimmering in your hair, the room catching fire all around you.”

We inhabit a dreamlike universe filled with fire and ice, where past and present mingle:

“Before I know it, we’ve started another fire.”

“I could already feel the sky burning through the ice on my dress.”

“Somehow you keep dreaming, heaving that frozen sky behind you.”

I love Darling’s alchemy of turning destruction and despair into something so exquisitely beautiful, painful, and seductive all at once. We’re reminded of the searing poetry of Djuna Barnes in Nightwood: “That’s what I loved about you. Somehow you just stand there, a handkerchief folded in your pocket, the room burning all around you.”

Through repetitions like mantras, incantations, iteration and reiteration, Darling weaves circles within circles, holding the reader captive and mesmerized:

“There was nothing I could do, so I kept trying to tell you good night.

“I could only stare.”

“By then I could hardly speak.”

“It’s the strangest things that keep me from leaving.”

“We stand there and watch…”

In their crumbling inner world, the two main characters are petrified and set afire at the same time, the narrator constantly on edge:

“It’s always the smallest things that put me on edge.”

“It’s always the strangest things that make me feel restless.”

She finds comforts in darkness and is unsettled by light: “and I was unsure if the light was a promise or a threat.” A very Jamesian sense of fatality is pervasive throughout the book. The narrator comes to terms with the implacable and finds a form of acceptance:

“By then I was sure there was nothing that could be done.”

“By then there wasn’t much that could be done.”

“I realized how little I knew about our house…”

“My desire to romanticize, I realized, had been a form of grief.”

A story of perseverance, testament to human stealth and endurance, mystery and ritual, The Sun & the Moon celebrates the redeeming power of beauty: “Still I wondered how you could ever leave, to live as a king without his court, without his crown.”

Making Ghosts Take Flesh: A Review of Eric Pankey's CROW-WORK

The title leads palindromatically: CROW-WORK.

The title leads palindromatically: CROW-WORK.

Caw and walk. It is as symmetric and opaque as the wings of the bird.

But as with all good repetitions, it involves a progression. We trade a “C” for a “K”. Crispin returns from the sea as Krispin, an imperceptible and apocryphal transition. The sea in Eric Pankey’s newest collection is the palimpsest canvas of the world, where bees invade a lion’s carcass, Buddha statutes are formed from ash of Junta sticks, “mountains wear down to silt. / The silt sifts into dunes. / Things move around—A snowdrift’s grammar.”

With these objects in tow, Pankey writes a meditation on the fringes of the material world where the divine effaces the poet at his work. The collection is richly allusory, with the opening poem describing a collapsing Buddha statue made by the artist Zhang Huan. These mystical considerations are accompanied by a poem on Venetian scenery, one on a still-life by Giorgio Morandi, and many others on foxes, crows, flowers, and the worlds they inhabit.

As the speaker interrogates these objects, we are invited to consider themes constant in Pankey’s work: encounters with the divine in the ragged wilds, how art can approach the phenomenal substance of the world in its semi-ordered but inscrutable forms, how the poet claims identity in this perpetual flux.

Each theme involves frustration and disenchantment. The reader is told to strike a rock in the desert, and nothing happens. Tension builds serially. “Rain. Clouds like ravens’ coats. A brawl of water over rock.” Images build upon image, often in fragments. Even when it rains, there is no climax or denouement, just constant flux: “Empty hills. Clouds bank against evening. / Voices in the distance, but no one in sight.”

This is the world the speaker is born into – frayed at the edges and needing stitches. Change abounds – again, mountains wear down to silt – but the transformation one longs for is always deferred to a later hour, a more distant hollow.

This evasiveness – evoking the Desert Fathers and Buddhist traditions – is the major substance of the book, challenging the will of the reader as much as it challenges the will of the speaker. Some poems bear fruit, “Record[ing] the last cache of August daylight / As the dark hollow of the plucked raspberry.”

Others offer chaff and stubble. However, the voice here is consistent, startling, and carries enough authority to keep us turning pages. Pankey is nimble, even virtuoso, with the meditative mode, and his voice is well-established. The tone of Reliquaries, Cenotaph, The Late Romances, and the whole line of Pankey’s prior publications is well-preserved in this volume. It is furthered in fragments and pieced-together poems in this volume, where variety creates a multi-tonal chord of harmony and disharmony.

This facility is seen, in “Fragment,” for example, where we’re shown an

Evening river.

A ladder of fire extinguished one rung at a time:The yellow of buckthorn berry, burry hatchings on gold leaf.

The tense of pain is the present.

From rivers to ladders of fire, buckthorn, and pain, these lines slide so fluidly from one object to another. In doing so they employ a Hopkins-like alliteration and a renga-like fluidity. I am particularly smug with the ladder of fire image, which equally applies to the river-reflected sun receding – and thereby being extinguished, as it retreats up the river – as to the early-autumnal blaze of the buckthorn berry.

In this way, the topical fluidity builds amalgams to mirror those that Pankey honors in the natural world. In doing so, they create a renga-like continuity of form spread across a patchwork of changing subjects, that is pleasing and productive in this botanical world.

Not all of the poems are so abundant with fruit, but there is a clear reason for that. This book requires a journey through the desert. Deliverance cannot come immediately if it is to be felt completely. As a result, thematic turns arrive later than the hedonistic reader would like them to. Regardless, this is a consummate work.

Consider the speaker’s dilemma in “Ash,” where we are taken to “the threshold of the divine.” The holy white noise of silence transmutes to a songbird’s habitation in a thicket, and the Buddha made of joss sticks stands before us.

With each footfall, ash shifts. The Buddha crumbles

To face it, we efface it with our presence.

And more so, we are effaced by it:

… turn[ing] away as if

Not to see is the same as not being seen.

There was fire, but God was not the fire.

This mutual effacement spans the seventy pages of this book, wherein the divine constantly retreats as the speaker advances, and the speaker grows silent, losing words and identity in the presence of the divine. In that progression, one is stupefied, for the

“blaze [is] so bright it would silhouette one who stood before it.

A blaze so bright

It would hide one who stood behind it.”

The erasure is so total that the speaker must be forgiven for thinking his body is gone. In a grocery store, he knocks “[s]omeone’s … bag from her hands” and is heard in his apology, somehow. Somehow she “[h]ears [his words] and makes sense of them. / (that is, it seems, the miracle: that I am a body, not a ghost;…).” To a writer, that is miracle enough.

We should all be so attuned to that reality, and Pankey calls us to that acknowledgment. The world is real, our bodies too, no matter how ghost-like our thoughts and aspirations may be. In that reality, Pankey also calls us to the crow-work at hand: surveying the wreckage from above, gleaning through the chaff, and piecing together our stories from mere vestiges of the original text.

The Logic of Jarring in Julia Cohen’s I Was Not Born

Julia Cohen’s collection I Was Not Born (Noemi, 2014) lives in the cleft between lyric essay and long-form poem. This at-once fractured and mythic narrative takes as its central drive the something that unfolds between two bodies when one of those bodies is dealing with the impulse of suicide. It is the story of N. and J., who fail, both independently and together. It is also the story of how that story unfolds, for J., our narrator, both confesses and withholds as she copes with the impossible task of telling.

Julia Cohen’s collection I Was Not Born (Noemi, 2014) lives in the cleft between lyric essay and long-form poem. This at-once fractured and mythic narrative takes as its central drive the something that unfolds between two bodies when one of those bodies is dealing with the impulse of suicide. It is the story of N. and J., who fail, both independently and together. It is also the story of how that story unfolds, for J., our narrator, both confesses and withholds as she copes with the impossible task of telling.

To say more than that about the story in I Was Not Born would be to populate voids that are very intentionally left empty, as we are not offered a comfortable arc with which to see a pair of people uniting or coming apart. Rather, the narrative follows the laws of collage, where juxtaposition is used to illustrate contradiction and echo. For example:

Jar the crab legs. Jar the white stones. Jar the chrysalis but punch holes through the lid. Jar the sparklers into smoke. Jar my cough. Give me back a pulse. Give me back my pile of paper. My clothing, clean hair. I am sitting on the stairwell is sickness, in pale face, in fragile gown, listening to dinner clink below. I drink juice, swallow ten pills at a time. I was taught to fight this body & no one told me how to stop.

The collection—which provides essays that live independently but also collect to craft a body of prose that explores themes as varied as illness, love, selfhood, and art—is bookended with two longer essays in which we are offered therapy transcripts of a discussion between J. and “Dr.” These interviews work to ground the more lyric and exploratory essays in the very concrete reality of dealing with a traumatized partner, ultimately producing a rich tension between aestheticizing the story and recording the ugly facts. The transcripts, which are highly performative in their employment of colloquial speech, live in stark contrast to the intense privacy practiced in the more poetic places, and calls to mind both the plays of Nelly Sachs—a figure who haunts the book as another woman dealing with a suicidal partner, Paul Celan—and the Socratic dialogue that has become so closely associated with asking questions not necessarily in service of finding answers.

This toggling between moments of grounding realism (“N. introduces me to H.D. & Deleuze, to riding a bike as an adult, to multiple orgasms, to broccoli rabe sandwiches & homemade sauerkraut”) and ontological questions about self and art (“What is a minor person?” “Do I live the way I read?”), suggest that the book adopts the narrative logic of the verb jar. Here jar has two, perhaps contradictory, meanings: to withhold and contain inside a closed space, and also to rupture the familiar through surprise. In this way, we read “if you have patience, jar it” both ways: keep your patience confined and also disrupt it. This is how the book itself jars; it is an attempt to collect and enclose the violent circumstances of living with a suicidal partner through recording and it is also a celebration of the refreshing possibilities of art that embraces instability and dis-ease.

As our narrator says, “Sickness takes a certain kind of patience.” Later she provides an example of the wait:

Who can pay attention the longest? So many songs come from the shower. Laminate leaves or clean out the drain, the grapes, the fury of its avenging families. Flies cling to memory like a cenotaph. Say aaaaah. Say ache.

What is revealed in this short excerpt is the rich possibility that resonates in that twilight space between sentences. A prose artist might desire to close this cavity, to permit bridges to surface where the gaps loom distant. But a poet working in prose here offers few bridges, requesting instead we jump and in jumping, risk. Or, to provide a metaphor more appropriate to Cohen’s uptake, the space between the sentences act like split skin, where the reader’s work is to suture the flesh of the story together. And this is how the book embraces a beautiful array of paradoxes; it is a narrative that offers somehow both a rough scaffolding and an empty casing, the bone frame and loose skin. Here the reader becomes not an audience for but an agent in the making of meaning, for those authorities on disorder in the body—doctors—repeatedly fold. “Say aaaaah,” our speaker demands, in effect requesting we open our mouth in service of the story. “Say ache,” our speaker demands. The book is both literally speaking the word “ache” (ten of its twenty-one parts are titled “The Ache The Ache”) but also—perhaps more so—the book itself is, like heartache or headache, literally suffering from sayache, or the pain that escorts the work of telling.

This ache-in-saying is made most clear in what I might argue is the book’s central conundrum; this is, How do we narrate the story of a human’s desire to end his own life? Or, perhaps more accurately: how do we narrate the story of beholding a human’s desire to end his own life, a human whom we happen to love? How do we narrate the attempt? Not incidentally, of course, the word “essay” comes from the Latin for “to try.” It might be that the only form willing to take on such a grave task is the essay.

If I Was Not Born is an object study in the art of jarring, it succeeds; not only does the book serve as a vessel for the haunted reality of locating the place where the self ends, but it is also an encounter with the suddenness of the unexpected. There is a poignant tension at work here between loitering in the present, arrested by the poem, and moving ever-forward through time, propelled by the story. The paradox performed by at-once feeling suspended and feeling compelled to advance is one at the center of perhaps our most complex human emotion: grief. Here Cohen performs grief to its exhaustion, and we, in reading, participate in “the ache the ache,” both riveted and troubled in the healthiest way.

“How to prolong the lyric moment?” Carole Maso asks in her essay, “Notes of a Lyric Artist Working in Prose.” The answer is Julia Cohen’s I Was Not Born.

Seven Days: A Review of Nick Courtright's Let There Be Light

Mourning lost divinity is hard to tire of. Repetition only demonstrates its relevance. Thus the chiaroscuro longing of “Assomption de la Vierge,” sets a fitting mood for a book that starts in the modern moment and traces back through cosmo-biblical time

Mourning lost divinity is hard to tire of. Repetition only demonstrates its relevance. Thus the chiaroscuro longing of “Assomption de la Vierge,” sets a fitting mood for a book that starts in the modern moment and traces back through cosmo-biblical time.

The Virgin Mary has left the frame of Earth. Rapacious hands remain. Granted, the Virgin is not the Godhead. She is the goose that laid the golden egg. There are other egg-layings in this book. Beings emerge into the now, as if laying their own eggs, chrysalis-like, but with a mathematical stop-animation immediacy, as the time-step goes to zero. An egret begets itself from one moment to the next. We are asked to ponder its ontology through the infinite parcels of time.

In his latest book, Let There Be Light, Nick Courtright takes the time step beyond zero, going into negative intervals. This narrative traces back through 14 billion years and 7 biblical days in a varied collection of verse, discussing the death of stray cats, lyrical bridge crossings, cosmic background radiation, animal hunger, and the like.

Some stylistic choices provide obstacles in that path: endings are often unsatisfactory and ellipses are serially inserted. But these frustrations withstanding, the body of work provides a compelling meditation on the inflorescence of time and the senescent circumstances of modernity, in a cosmo-eco-biblical fullness found few places in verse.

Particularly satisfying are the lyrical modes pushing out against the time-conscious themes of this book. For example, the flagship poem “The Big Bang”, features “a finch making its sound from inside of joy,” an occurrence which only arises after the quanta of days, hours, seconds, weeks have been abandoned. “I thought, this, a day, is not a fraction I have to recognize / … nor the other products of separation.” The tweeting is brief, and its sound is enveloped by the surrounding rush of time, as if a wind. But still, it fights against that wind.

This is what good poems do, like finches: they expand the realm of the now, pushing out against the flow of time. Courtright does that in a poem about departure:

I walk through the front door, and you say

One day you will wake to find yourself finished.I walk through the front door. Look at the time,

you say. Look at the time.Your bags and my thousand flaming trees are full.

Hills fall over each other, rumpling their outfits.

“Look at the time” works ironically: the season and this relationship are late in their course, yes, but the moment commands more than its allotted span of minutes. In that sense, “Look at the time” says: I’d rather not talk to you anymore. Departures such as this become a part of the eternal present-moment for the grieving remnant. In this way, endings in this book can serve as fundamental lyric: when a sequence is cut short, it enters into a timelessness where all the preceding events are enshrined.

But the lyric that holds most prominence in this book occurs at the beginning of time. It is the ineffable presence of super-compressed proto-matter that exists before the big bang. This reservoir, immune to time’s arrow, mirrors a pre-expulsion Eden, mirrors the first day of a child’s life where everything is new, mirrors and presages every other lyric which pauses in the present while future potencies bide their time.

This Edenic lyric persists in fragments: angelic egrets stand guard as symbol and flag; a traveler pauses mid-bridge and sings reassurance to herself; riparian thought abides in black-faced gulls and barges that “pour their enormous stomachs across the river.” Time still flows in these echo-lyrics, but at a pace that suggests infinitude and continuity with all previous moments. It is worth dwelling in such moments, and Courtright’s incessant reminder of time’s cruelty empowers us to do just that.

The scientific perspective is key to knowing such cruelty, and Courtright uses it efficiently for that purpose. In a poem titled “Intelligent Design,” Courtright maps the age of the Universe against the metric of human existence. In “Lost on Planet Earth,” Earthworms move the terrain beneath our feet, making it suddenly new and alien when we look down again. This is what Courtright calls us to do repeatedly: to look down at the Earth that has changed and ask, “Is this okay?” instead of “and God saw that it was good.”

Consider, in turn, the romantic longing that the cosmic in this collection provokes. In “The Deep,” the faint electromagnetic hum from the big bang – i.e. cosmic background radiation – is presented as “a phone ring[ing] unanswered into the vast universe.”

“Please, please eternity, leave your message –” the speaker pleads.

In this despair, Courtright’s own plea for the lyric rings out in the space of this collection. It is a thrilling meditation on the form, one which presents many sounds of the immutable and the corrupted.

Skynet Becomes Self-Aware At 2:14 A.M. Eastern Time, August 29th

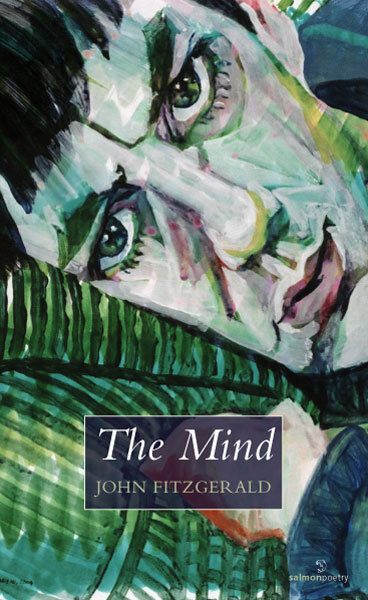

If I were teaching from John’s book, I would encourage poetry students to examine his masterful skill with personification. I would encourage philosophy students to wrestle with his experiences of phenomena. I would ask psychology and neurobiology candidates to experience the brain from inside-out.

If I were still working with John Fitzgerald (in the interest of full disclosure, we worked together at Red Hen Press), I would nudge him and say of his book THE MIND, “Skynet becomes self-aware at 2:14 a.m. Eastern time, August 29th.”

My sense of John is that he has been aware of himself for a long time, but not in a solipsistic or narcissistic way at all. He is a keen observer, a consumer of origins, fine distinctions, continua, grand schemes, and minute details. He likely began observing and contemplating information from the moment he experienced the glare of light in the delivery room, and he has never stopped.

Interestingly, while THE MIND is about the remarkable way John thinks, it speaks to the larger questions of how we all think, how we came to be sapient in the first place, and how we develop as thinking souls in space and time. Keeping the language of his prose-like tercets basic, unadorned, and free-flowing, he accomplishes poetry of significance and elemental beauty. Left brain contemplation of structure and systems aligns itself with right brain wonder and whimsy, but neither hemisphere dominates in the work, so the reader can only expect the unexpected. And the rewards are great: poems of curiosity, orientation with the universe, sorrow, finding center, and surprising hilarity. (Only John can make the idea of rocks funny.)

If I were teaching from John’s book, I would encourage poetry students to examine his masterful skill with personification. I would encourage philosophy students to wrestle with his experiences of phenomena. I would ask psychology and neurobiology candidates to experience the brain from inside-out. I would ask physics students to explore how we process space and time in an era when such concepts are continually challenged and updated. I would ask divinity students to consider creation from the point of view of the created. THE MIND weighs so many approaches to thinking and being that you won’t devour it in one or two sittings. Read it as you would the Book of Genesis, or Hawking, or an introduction to meditation. You will not think the same way ever again after reading it.