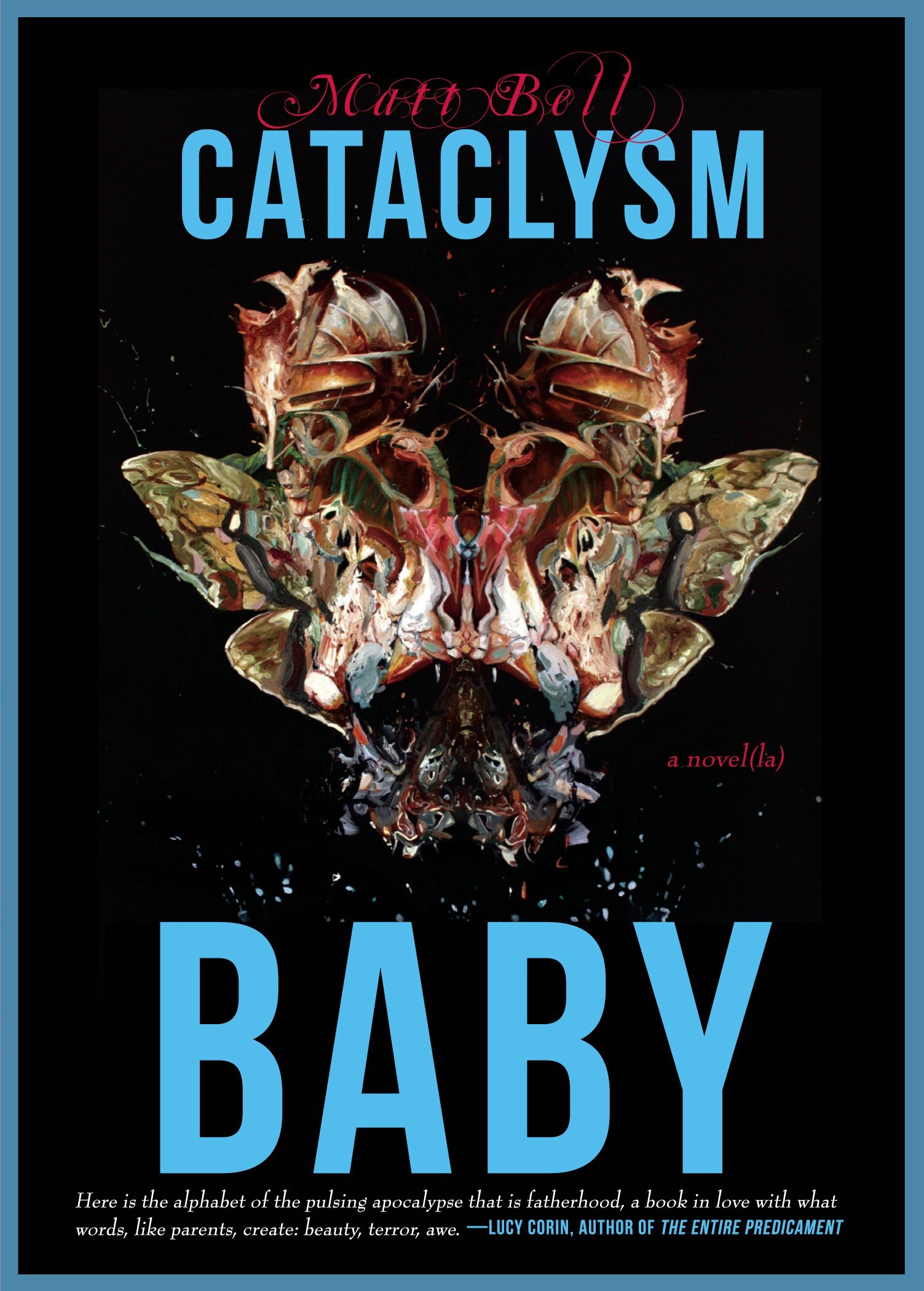

How to Save Your Friendships: A Review of Matt Bell's Cataclysm Baby

What keeps Cataclysm Baby from being just another menagerie of impossible disasters are the variations in the fathers themselves, who each struggle to deal with the guilt, anger, pride, and obligation fatherhood brings with it, apart from the apocalypse-fractured world outside the window. Some fathers regard their strange children with single-minded affection, others with scorn. Some sacrifice their mutated children, and some others sacrifice themselves. As the lights go out on the human race, some cling to hope that their children represent some sort of future, while others hold onto only what they can.

You know when someone develops a deep love for a movie, TV show, book, or video game and, before too long, it’s all they’ll talk about? Or how repugnant your sister is in the first few weeks of her new romance? We, as humans, are compelled to express our deep love for things, a habit which will murder your relationships unless you find people who love the same things you do (the reason people who like weird stuff like dubstep and electrocution tend to gather together).

This isn’t really a recommendation that you buy this book. Matt Bell’s name on the cover should be all the incentive you need to do that. But when you buy Matt Bell’s Cataclysm Baby, which you absolutely should, I’d recommend you buy at least a dozen copies, or one for each friend and family member you’d miss when they get tired of you obsessively talking about this book and stop returning your calls. Supplying all your loved ones with copies is an invitation into your new-found pleasure and will hopefully keep them from having sudden emergencies just as you arrive and staging interventions.

And talk about this book you will. You’ll talk about Bell’s prose, some of his finest yet, which has something of the biblical in it, something of the prophecy. About how you can imagine these stories told in dusty, burned-out rooms by grizzled fathers with thousand-yard stares sliding down the other side of survival. You’ll talk about this passage, and dozens more like it:

The day [my son] turns thirteen, he tells me I will wait three more months before I sneak into his room and read his diary, and that by then it will be too late.

He says, I know you could save us if you read it today, but I know you won’t.

You’ll talk about the references, the intelligent re-workings of Greek mythologies, Arthurian legends, and biblical stories. The Sirens make an appearance as three daughter mimics, luring villagers out into the floods destroying their world. A man, driven by the ghosts of his daughters, builds tower after tower, not to get closer to God, but to find the voice of his wife. A tanker carrying the world’s last women floats off the West coast, waiting for the world to be clean enough to deserve their return. A man chooses his own calf-child for sacrifice in a lottery. Bell’s handling of the sources is elegant, keeping to the core of what the stories are about, and might provide enough conversation material to ensure that your favorite barista will never ask how your day is going again.

You will probably, more than anything else, talk most about the endless variety Bell achieves, despite adhering to a restrictive formula. In almost every story, children are born deformed, mutated, something other, into a drying out or burning or drowning world. Of course, Bell shows off his impressive imaginative range with the “wrong-born” infants: some only balls of fur, some born as only invisible puffs of air.

What keeps Cataclysm Baby from being just another menagerie of impossible disasters are the variations in the fathers themselves, who each struggle to deal with the guilt, anger, pride, and obligation fatherhood brings with it, apart from the apocalypse-fractured world outside the window. Some fathers regard their strange children with single-minded affection, others with scorn. Some sacrifice their mutated children, and some others sacrifice themselves. As the lights go out on the human race, some cling to hope that their children represent some sort of future, while others hold onto only what they can. The family dramas, the reality of the fathers in these stories trying to hold onto a world that inexorably spins away, keep these stories from being just another meditation on the ways the world could end.

And the end. You will talk about the ending, the last chapter.

Obviously, this is the kind of book that can leave a reader sitting by himself on the bus, other passengers clutching purses and children while he mutters under his breath about how no one reads great books anymore. You don’t want to be that guy, so get a dozen copies. More if you actually like your family.

Peter Markus's We Make Mud

It is a prayer. It is a collection of fairy-tales in the most serious of ways. There is violence, but it is never for the sake of violence: it becomes ritual. And the repetition is part of this. It is a prayer about childhood and what it means to have a single place, a river, be the entire world.

But us brothers, we knew what it meant to be better than dead. We knew that when things die they sometimes just then begin to live.

It is moments like this within Peter Markus’s We Make Mud that make you read and reread sentences over and over. So simple and so understated, but, in many ways, those two sentences are at the very heart of this novel in stories.

Told in plural first person with the occasional transition to singular, a story about two brothers who call each other Brother, not Jimmy or John, which, as we’re told by them, are their names. There are a few other characters, but mostly it is the brothers. The most noticeable thing about this book, these stories, is the prose. It is not the kind of prose that shimmers ecstatically. It is deliberate and in such a way that it changes what you thought fiction writing could be. Not because it’s maybe somehow the way everyone should’ve always been writing, but because, for the first time, you realize that writing can look like this, can feel like this. There’s a distinct rhythm to the words and the syntax and grammar of the sentences should be awkward, but somehow manage to never be. Repetition is usually seen as a bad thing in prose, but these stories delight in repetition, and it works to a dizzying degree. And the book is built on this repetition of phrases, of scenes, of revisiting variations of already told stories. And that’s part of it, too, not only to repeat, but to vary, in the way that jazz uses variations on a theme to expand upon the initial melody.

And it turns this novel into rituals and prayer. It is a prayer. It is a collection of fairy-tales in the most serious of ways. There is violence, but it is never for the sake of violence: it becomes ritual. And the repetition is part of this. It is a prayer about childhood and what it means to have a single place, a river, be the entire world. Told by brothers who are children, reality bends and blurs and the impossible becomes common, either as daydream and fancy or actuality, the reader never knows for certain. It is a book that surprises and delights even as it becomes ugly and course but more so as it shimmers and grows, glowing.

We are brothers. We are each other’s voice inside our own heads. This might sting, us brothers will say to each other brother. Us brothers, we will raise back the hammer in our hand. We will drive that rusty, bent-back nail right through Brother’s hand. Neither of us brothers will wince, or flinch, or make with our mouth the sound of a brother crying out. Good, Brother, Brother will say. Brother will be hammering in a second nail into us brothers’ other hand when the father of us brothers will step out into the back of our backyard. Sons, our father will call this word out. Both of us brothers will turn back our boy heads toward the sound of our father to hear whatever it is that this father is going to say to us brothers next. It will be a long few seconds. The sky above the river where the steel mill sits shipwrecked in the river’s mud, it will be dark and quiet. Somewhere, though, the sun will be shining. You boys be sure to clean up back here before you come back in, the father of us will say. This father will turn back with his voice and go back away into the inside of this house. Us brothers, we will turn back to face back with each other. Us brothers will raise back with our hammer, will line up that rusted nail.

There are so many more moments I wish I could put in this review as I found myself highlighting almost whole pages. Because it is not the sentences themselves that hit hard, but the images that Markus builds over the course of five or ten or forty sentences: surreal, surprising, dark, beautiful, grotesque, magical.

We Make Mud is a great and short book.

Nothing Is Revealed that Won't Be Important Later: On Francine Prose's Blue Angel

I bought my copy of Blue Angel by Francine Prose for a few thin reasons. First, I was tickled that someone who wrote fiction would have such a fortunate last name. Second, the cover intrigued me: a black-and-white photo of a student and teacher, focused on their studies except for the fact that the student holds up the back of her skirt. I

I bought my copy of Blue Angel by Francine Prose for a few thin reasons. First, I was tickled that someone who wrote fiction would have such a fortunate last name. Second, the cover intrigued me: a black-and-white photo of a student and teacher, focused on their studies except for the fact that the student holds up the back of her skirt. I probably read the first few paragraphs, too, and noticed the accolades on the cover, but mostly I remember the image. I was nineteen years old and had decided that I most certainly would judge books by their covers. I spent about six months browsing the shelves at Barnes and Noble, purchasing books based on cover design.

This is not to say that I knew anything about graphic design. It means I was (and probably still am) susceptible to certain cues. I tended toward images of young girls: a pair of scraped-up knees and the hem of a skirt, a freckled face with red lips and a cigarette, skinny shins sprouting from sneakers. Analyze this how you will, but it led me to stories about girls around my age, almost all of which helped me wrap my head around my own life.

I didn’t go straight to a four-year university despite the fact that my grades and test scores could have gotten me in most anywhere. I had spent half my high school career involved in the theater department at a local community college, and when I graduated, I didn’t want to leave. I enrolled full-time, paying my own way with the token scholarships I’d received from Kiwanis, etc, and lived at home. For the first year, I was almost sublimely happy with the situation. I’d helped a friend move into her dorm at UCSD and the experience terrified me; I was much more comfortable in classes full of adults and running-start high-schoolers than I would have been in a pool of my so-called peers.

But as happy as I was at the beginning, when my first two years of school ended, I was more than ready to move on. I was not only done with my general education courses; I was done with the theater as well. I wanted something more permanent, without the constant cycle of auditions, something that wouldn’t change from night to night and then disappear altogether. I began to write stories: dark, terrible things in which girls like me performed melodramatic acts (I was socially stunted and nineteen, after all). I had been writing — mostly fiction — off and on since I learned my letters, but now I saw my work differently. This was art. Maybe it was bad art, but I could learn how to make it good art. I had to read more good books and find out what good art was, but aside from the classics, I didn’t know where to look. So I went to the bookstore and judged books by their covers. Thus I found Blue Angel.

It starts in a creative writing classroom, in the mind of Professor Swenson as the students get settled before class begins. Perhaps Swenson’s judgments of his students and their work should have scared me off a course of study in creative writing, rather than piquing my interest. Of course, the presence of Angela Argo, the deeply troubled and talented antagonist, provided proof that not all fiction students are judged harshly. Angela’s talents provide Swenson with all the attraction he needs to become entangled in this unlikely student/teacher affair. Her novel within the novel provides Swenson a happy diversion: from his teaching duties, his writing, his own family. He pours his enthusiasm into Angela’s writing, and though he surprises himself by doing so, into Angela herself, until he is trapped. While he’s thinking about love and art, she’s thinking about publication. She exploits Swenson’s connections, his personal life, and the political climate of the school — ruffled by a sexual harassment case at a nearby college — to get what she wants and come out looking like a victim.

We spend the whole novel inside Swenson’s head, so it seems possible that all this plotting is in his imagination. Except Blue Angel is one of the most carefully plotted and foreshadowed books I’ve ever read. It’s as tense as a thriller, but with stakes that feel supremely real. From the opening paragraph, nothing is revealed that won’t be important later, a fact that made this a perfect transition from plays to novels. Prose adheres to Checkov’s rule, “If in the first act you have hung a pistol on the wall, then in the following one it should be fired.”

My connection with Blue Angel will always be more than the combination of words and characters and a story. It kicked me in the pants and sent me stumbling toward creative writing, a path down which I would eventually find myself, quite unwittingly, the student of a man who had been taught by Francine Prose. I’ve since had a lot of guidance in my reading, but hundreds of books later — a few of which also deal with academia and the student/teacher affair — I’m still impressed by Blue Angel’s style, its characters, and its tight construction. It’s the first book I ever read that combined engaging plot with sharp writing: a combination that still feels rare

Creating Negative Space, Showing Us the Ways We Fail, the Ways We Lose Our Humanity

I’ve known Caleb Ross for a few years and his writing’s always visceral — both grotesque and erudite — and As a Machine & Parts is no different.

I’ve known Caleb Ross for a few years and his writing’s always visceral — both grotesque and erudite — and As a Machine & Parts is no different.

A man, inexplicably, begins to transform, and his transformation is almost Kafka-esque. But, more than his transformation into a machine — certainly the most obvious part of the novel — is Caleb’s focus, which is not about becoming a machine, but what it means to be human.

This novella is about relationships, how they’re formed, and the ways they can fall apart, and the ways we change. This, I think, is what all great literature does, and I know it’s the question at the center of my own writing: what does it mean to be human?

It’s a quick read and it kept me up while I raced through its pages, even sending him a Facebook message when I finished, sometime in the middle of the night, which, I suppose, is just when I tend to be wandering the Internet the most. But his novel really hit me, not just that night, but for the rest of the week, and even now, three months later. It still sticks in me as I battle with the questions that haunt me, trying to sort out what it means to be human, and how, perhaps, one day I’ll be one too.

To be human, all my life grappling with that desire. And it’s stories like this that make it somehow clearer, by creating negative space, showing us the ways we fail, the ways we lose our humanity, the ways we long to even just cling to that which makes us human, that we learn how to be.

Human.

And even while our narrator loses his humanity, so too does the text lose its humanness. The page itself transforms, the structure moving from a standard storytelling model to schematics and diagrams, an instruction manual designed to show us what we’re reading. Something I’ve always loved about Caleb’s writing is how visual and gripping his images are, and, here, he’s married his language to concrete visuals, pushing his storytelling past what I thought it could be.

This novella about heartache and love and identity and humanity is also just completely fun. It never gets bogged down in its own peculiarity or tragedy, simply accepting the transformation as a matter of course, allowing for laughs even while the story reaches deep into your bowels.

Glimpses of Personal Secrets, Situations of Real Human Beings: Roxane Gay's Ayiti

Gay’s first book, Ayiti, is infused with every one of her blog’s virtues: it’s funny, sad, bristling, kind, and contemplative. The collection comprises stories, poetry, and nonfiction, and the divides between the three are artfully blurred.

Ayiti is the first book I have ever read by an author whose work I discovered on a blog. Roxane Gay is a regular contributor to HTMLGIANT, “the internet literature magazine blog of the future,” which I unearthed (and obsessed over) in my senior year of high school, desperate to become a part of the “indie lit. scene.”

I enjoyed Gay’s posts so much that I began following her personal blog where Gay writes with wit and heart about writing, rejection, teaching, her life — oh, and films, brilliantly, uproariously. (I read her reviews of both Transformers 3 and Breaking Dawn at work and nearly choked trying to suppress my laughter.) To this day the only things online I check more frequently are my email, Facebook, and xkcd.

Gay’s first book, Ayiti, is infused with every one of her blog’s virtues: it’s funny, sad, bristling, kind, and contemplative. The collection comprises stories, poetry, and nonfiction, and the divides between the three are artfully blurred. Its subject is Haiti, its central topic the Haitian diaspora experience, but its themes — among them the strength/fragility of familial bonds and the real cost of human dignity — run far deeper.

It is refreshing, after reading and hearing ad nauseam the same maudlin but feel-good narrative about Haiti, to see its stories told tenderly, straightforwardly. Like most great literature (and unlike much shameful journalism), this collection profoundly respects the complexity and diversity of the situations of real human beings.

Gay’s prose is patient and, better, patiently-revelatory. Ayiti is smart but never erudite. Frequently, the pieces feel like glimpses of personal secrets. The reader plays the role of close confidante, a receiver of souls spilled forth.

The first piece, “Motherfuckers,” begins: “Gérard spends his days thinking about the many reasons he hates America that include but are not limited to the people, the weather, having to drive everywhere, and having to go to school every day. He is fourteen. He hates lots of things.” Gay knows how to express complex truths, evoke specific senses, without asking the reader to meet her halfway.

In November, 2009, in a blog post titled, “Wish I May, Wish I Might,” Gay worried about the fate of Ayiti, then unpublished. Was it too “ethnic” for publication? She wondered, “Are there any independent publishers who don’t mind such intensely thematic writing? When I see what’s being published, I really worry that there just isn’t a place for a collection like this to find a home.” This story ended happily — Gay’s beautiful little book found its home — but the questions behind her worry remain relevant, even essential.

Ayiti is unapologetic in its focus. It is brave enough to concern itself with a million facets of human life, to employ unique lens after lens, without wavering in its decision to be about Haiti and Haitians. This quality is rare in modern American literature. Ayiti, I hope, will be encouragement that collections of its kind are valuable, even necessary. But it is, of course, an outstanding debut before it is a political statement. And more than anything I hope it is a step toward earning Roxane Gay the readership her work has long deserved.

Finding The Right Strange Details: On Stefanie Freele's Surrounded by Water

I had such a good time reading Stefanie Freele’s Surrounded By Water. I knew I would. I’d been looking forward to it with giggly anticipation you might say. Freele is a writer who does the thing I like most in literature, and that is she writes stuff that only she could write.

I had such a good time reading Stefanie Freele’s Surrounded By Water. I knew I would. I’d been looking forward to it with giggly anticipation you might say. Freele is a writer who does the thing I like most in literature, and that is she writes stuff that only she could write. Reading her is a chance to look into a mind very different from your own. And those differences matter. It’s not like looking into a different mind and only seeing blank white walls or flashing lights or oh look aren’t these people awful and weird and aren’t you glad you don’t really know them? No, Freele is a writer who finds the right strange details and makes them matter in an entirely sympathetic and very human way.

I knew there would be lots to open in this new book. I was a kid creeping down the stairs on the it’s-mine-all-mine holiday morning before anyone else is up, squeak slap squeak slap on the stairs with my flip-flopping slippers. It turns out there are 41 stories and each of them is a remarkable package.

Many of the stories are very short, and that got me thinking about very short fiction, and that led me back to Sudden Fiction International (recommended below). I had forgotten that Charles Baxter wrote the Introduction. This book is where I first read Dino Buzzati (also recommended below) who Baxter also discusses recently in Ecotone 13. Sometimes the coincidences of life seem totally scripted like all the world’s a stage or something. Baxter starts that Ecotone essay talking about new writers, and at one point he says, “The result is Unrealism, our new mainstream mode.”

I think that is probably right. We are back to the fantastic as our major mode but in a way that reflects our times. Some of the best stuff is a kind of interior/exterior bleeding and blending, you turn your head inside out, and Stefanie Freele is very good at this. I’m looking to be surprised when I read stories like these. I want to see details, thoughts, and situations I would never have thought of myself. Then it’s just me and this strange new story cheek-to-cheek in the candlelight.

For example, I’m reading her story “A Bunch of Cash Landed My Way” and in the background I’m hearing Barenaked Ladies singing, “If I Had a Million Dollars.” It’s what I bring to the story. The song might be longer than the story. They probably have nothing to do with one another except in my head. If I had a million dollars I’d buy a big statue of a butt and put it in front of a bank, oh wait. . . .

Or consider the story called “Quack” where the narrator is to have dinner with Lydia but has neglected to invite her. It only gets better. Dinner happens. Lydia is both there and not there. Wonderful.

There is a strange and sinister boy in the complex story “While Surrounded by Water.” There is a town and a storm and a flood, and the people who do not flee are isolated both from the outside world and from one another. I thought of Ballard’s The Drowned World. Freele’s atmosphere and intentions are entirely different from that novel, but she succeeds in setting up a fully realized world with people like islands surrounded by water.

You will have your favorite stories in this book. Mine is probably “Us Hungarians.” Freele gives us deeply imagined and richly described details that are both very strange and very human at the same time. There is a woman with a hair disorder and a sloppy but remarkably tight family bond between another woman and her two brothers. There are dump sick wobbly seagulls. And cows. And Romance. And most of the people are Hungarians.

The twist, the thing you do not expect, is the genuine family bond between Allee and her brothers, the “us” part, or part of the “us” part because there is a very tall girl with a hair disorder (her bright red hair grows forty times faster than normal) and her weird father who are also Hungarians if less admirable ones.

Allee has run off to Massachusetts from Wisconsin (apparently the homeland of the Hungarians, who knew?) to go to school, but now she is visiting her brothers in California where they have rented a cottage on the grounds of a dump. The place is always wet and it smells. There are toxin dazed or crazed seagulls everywhere. Eagles are supposed to swoop down and eat them which can’t be good for the seagulls or the eagles.

When Allee arrives she notices her brother Steyr is bigger than ever as expected, since her other brother Kurz told her on the phone, “He’s turning into Elvis.” Don’t you love that? Isn’t it perfect?

The house is in a state you would expect a house inhabited by your older brothers to be in. Messy. The details are all great. Is Allee resentful? No. Is she disgusted? No. Does she try to clean the place up? Well, a little. Everything that happens in this story is surprising but just right.

And there is something about the landlord, Werner Waffin, the father of Haenel, the girl with the ever-growing red hair. “Rule #1,” Steyr tells Allee. “Never ever open the door to Werner Waffin unless we’re here.” It wouldn’t really be a spoiler to tell you why, but it will be more fun for you to find out for yourself. In the end, you will love these people. You will wish you were on such terms with your own relatives. You will all want to be Hungarians, too.

Consider This My Warm-up Lap

In I Was The Jukebox, the orchid speaks, the eggplant waddles, and the piano shimmies through seaweed like salamander. These are the sorts of characters you’ll meet. They’ll crowd and shove and step on feet trying to get your attention, some more patient thanpeople in line at the DMV and others all aclammer to be heard.

My first encounter with Sandra Beasley was last summer. I was teaching finance to high school kids, in class six or more hours a day and prepping for countless more, yet it was poetry not numbers that was most on my mind. On exam days, I would ever so discreetly read from my computer while the students penciled away and the TA thought me busy with the next week’s lesson plans. This was how I came across Beasley’s “Unit of Measure,” the unit there being the capybara. Do you know of the capybara?

Everyone barks more than or less than the capybara,

who also whistles, clicks, grunts, and emits what is known

as his alarm squeal.

At these lines I let out a laugh, a chortle more like. The others looked up with faces unsettled between amused and annoyed. I kept my secret.

Fast forward to the colder months. A package arrived from the opposite coast, from a poet friend who was the first (and one of few) to know of my secret love for verse, and inside was a copy of I Was The Jukebox with a note that read: “Sandra Beasley is hilarious, and I think you’ll have fun with this collection.” Scanning the contents page, I spotted the title “Unit of Measure” and gasped. How did she know?

In I Was The Jukebox, the orchid speaks, the eggplant waddles, and the piano shimmies through seaweed like salamander. These are the sorts of characters you’ll meet. They’ll crowd and shove and step on feet trying to get your attention, some more patient thanpeople in line at the DMV and others all aclammer to be heard. When the sand speaks, it’s with command:

. . .Draw

a line, make it my mouth: I’ll name

your country. I’m a Yes-man at heart.

But inanimate objects aren’t the only ones present. Osiris and Beauty make an appearance. There are poems on music and the Greeks and love poems for college, Wednesday, and Los Angeles (my favorite). In “Cast of Thousands” the speaker takes us to war, explaining how “They buried my village a house at a time, / unable to sort a body holding from a body held,” and when we turn the page, it is the World War’s turn to speak.

The gifting of books is a dangerous practice and an art I aspire to master. I’ve given novels and children’s literature and even coloring books, each one with a few thought-out lines on why it was chosen for that particular person. But recommending poetry? And to readers at large? That is a habit I have yet to adopt. Consider this my warm-up lap.