An Interview with Sheldon Lee Compton

So, you establish this grave sense of danger, and this insular need to protect self, family, and to defend against that ‘evil’ at large. Willing to address this? Is this a recurring theme in your work?

Robert Vaughan: Hey buddy! I was up in Boston over the weekend for Tim Gager’s DIRE literary Series and I fell into a time warp. Good news is I was able to start reading your book, The Same Terrible Storm. Man, can you write! I’ve always been an admirer of your craft. We’ve crossed paths in many different places online, and off. But I was drawn into your stories immediately, and can’t wait to dive into the interview. Such an honor to get to chat with you about this heavily awaited book. So, let’s start at the beginning. How long have you been working on this? How many drafts? Tell me about the progression of this “final” birth of your book.

Sheldon Lee Compton: The Same Terrible Storm is a collection of stories completed over the period of about three years, many of them published in some generous literary journals and others just now seeing the light of day. Of the stories in the book, I’d say I put each through three or four drafts for the longer stories and a couple for the short-shorts. This was a decision that came fairly late after talks with Stephen Marlowe at Foxhead Books, the press that published the collection, the idea to include both long stories and shorter stories in this collection.

I can’t say how happy I was to have a collection on hand for Stephen when he and I first talked about my sending something to the gang at Foxhead. I sent two collections – one that became The Same Terrible Storm and a second titled Where Alligators Sleep, which is exclusively short-shorts. I had a lot of input on the book itself, from the final content to the cover, which was handled by the talented Logan Rogers and his crew. My plan for the next collection is to add several short-shorts before publication, maybe even double the number of stories currently in the submitted draft.

RV: Sounds like such a dream come true. Also, this organic process you describe (varying lengths of stories turned into a collection or anthology) seems to be more common currently. It’s great that you had such a supportive team at Foxhead, makes me thrilled to hear this score for indie presses. I wanted to discuss your opening story of TSTS, I was so immediately captivated. You build such a fierce, tender relationship between the narrator and Mary, and son, Dennie. From page 5:

‘I don’t even like insects to bite her. That’s how personal I take it.’

Also: ‘But Dennie was to be raised Christian and that made learn- ing hand-to-hand combat maneuvers tricky. Self-defense didn’t fit into Mary’s plans all that well. But she knew the world was mean, cruel and hard, so she left it alone. Only thing, she didn’t want to see Dennie coming at me with sweep kicks and throat strikes, so we stayed at the east end of the field, away from the house. I felt like I was in a familiar place out there in the field, just like in the war. It was those times out there with Dennie when I would go hours without a drop of anything, and not even miss the smell. If we could’ve stayed in that field forever, hand-to-hand, learning how to keep the world from swallowing us up, I might have had a better chance at being a good Christian.’

RV: So, you establish this grave sense of danger, and this insular need to protect self, family, and to defend against that ‘evil’ at large. Willing to address this? Is this a recurring theme in your work?

SLC: I for sure inject that sense of danger you’re talking about with most of my work, but I suppose it’s not always an evil-at-large type of situation. Often the danger is very focused. But, as anyone who reads the book will see, the stories are set in Eastern Kentucky and this region often functions as a character in its own right, and usually in opposition to the hopes and dreams of the people who populate my fiction. I’m not trying to make the place I come from worse than it is, but at the same time I’m not interested in sugar-coating anything, either. When I write about the people I’ve grown up with and live with now, most folks are of one of two mindsets — there are those who will argue that the mountains that surround are protection from the rest of the world, or those who feel the mountains are hardly more than prison bars, stopping any notion of improving our lot in life. This is a black and white sort of thing, and something I like to do is find the gray in those instances. It’s what I hope I’ve achieved in this book, nothing is completely honorable and nothing is without a certain amount of darkness. But if there is a consistent danger or opposition throughout my work it would be the character’s region. Whether you love the mountains or hate them, this region plays a huge role in the lives of most Appalachians.

RV: I love that you addressed the region, which functions as a character (in its own right) because I feel you have such eloquence in how you write nature and environment, how it shades a story. For example, from page 12: ‘Then the drizzle lifted off, back into the clouds, which moved away in a slow bulk across the ridge and dissipated like a swarm of colorless wasps.’ It is breathtaking, the imagery so poetic. I also admire your use of character names: Burl, Spider, Torch, Mackey, Murphy…how do you decide names? Do they decide you? Also, the “double” tag names with real and call names like Michael/ Spider and Caudrill/ Torch. Are names important? If so, how?

SLC: I’m thankful for your attention to my attempt at a certain lyrical style, Robert, I truly am. Two of my influences as a writer are Breece Pancake and Michael Ondaatje, whose styles could not be more different. Pancake’s is muscular and tight, while Ondaatje writes in that highly poetic way that always reveals the poet inside him. So my influence from Pancake was in how to write honestly about my region, while I tend to lean to Ondaatje as inspiration for the individual sentence, its texture, sound, feel and possibilities. I work hard at blending these two literary devices in my work, and so I do so appreciate when anyone notices. Nature is a given with regional writing, and so it’s more often the place where I can allow myself to use a more poetic voice, even if the story is about slaughtering a hog or working at a junkyard.

I do give a fair amount of thought to character names. There are so many colorful names where I’m from that I often find myself meeting people and then writing their names down as a reminder to later use them in whatever I may be working on at the time. Each one you’ve pointed to here were either names of people I met or worked with or heard of through some local source. Spider and Torch are actual call names of two truck drivers from Eastern Kentucky. Somehow I knew I’d use them in my fiction at some point. I simply couldn’t resist. One of my favorite character names was German — a character from an early draft of the story “Snapshot ’87.” I hated to edit that character out when revising only because I liked the name so much. It was taken from a guy I worked with in the coal mines when I was a teenager. It was his birth name. I still find that terribly cool.

RV: Names in general are cool! For instance, I love that you call me “hoss.” Even though you might call everyone this, I’ve often wondered if I ought to respond by calling you “little Joe.” With all brotherly respect, of course. Tell me a little about your writing life- do you write in the morning? Only certain days? Computer or long hand? How do you tap into a muse, or is that just horseshit?

SLC: Nothing but brotherly for you there, hoss, and feel free to lay some “little Joe” on me! The writing life for me is a full-time job and I’m thrilled about that. In October and I took the leap and left the workforce until very recently. While writing full-time I worked about eight to ten hours a day, waking at five-thirty in the morning and working through the day, allowing myself a couple breaks here and there and an hour for lunch. I found the old saying that it takes a great deal of discipline to pull that off is so very true. The upshot is that even though I’m back in the workforce, I can still manage about six hours a day of writing, doing most of the work in the early morning before I ever leave for my grunt work. Other than needing that instant gratification of the computer for the actual process, I don’t have many tangible needs to write. I once wrote in longhand, but since college my penmanship is simply too poor. I can write a note and if I don’t refresh myself before bed by going over it I’ll not be able to read it the next morning.

Like all folks in this craft, I gain my inspiration, if you can call it that, by reading. I can read a passage from Barry Hannah and get really pumped about trying to write that clean and naturally, or pick up books like How They Were Found by Matt Bell or Mel Bosworth’s Grease Stains, Kismet, and Maternal Wisdom and Mostly Redneck by Rusty Barnes, just to name a few, and be reminded that I actually know writers who are doing it right so it can’t be too far out of reach for me. Sometimes just turning other people’s books over in my hands and reading the blurbs is enough to remind me that this work can be done and done well. The trick for me as a writer of fairly heavy themes is to not take myself too seriously while doing it, though. I usually write about Eastern Kentucky, as I’ve said, and the people here. Most of what has been published until the last five to ten years about Appalachia has been a little too soapbox for my tastes. It’s difficult to write about a culture and keep social commentary out of the picture, but I hope I’m coming close by concentrating on the characters and simply telling their story in an entertaining and compelling fashion.

RV: In your last response, you touched on the subject of themes in your work, referring to yourself as “a writer of fairly heavy themes.” In this collection alone, you broach religion, divorce, drinking, single parenting, blue collar jobs (and unemployment), lies. Can you tell me what draws you to what you write? Does it come organically, or are you turning life into fiction (to draw from Robin Hemley’s great book about craft)? Do themes come to you as you craft a story, or are you aware in advance of what you will be delving into for a certain story? Also, where do you find the motivation for your stories? You mentioned the Appalachians and breath-taking region in which you live, is there more? Maybe give us a tale not yet written . . . what’s something you’ve not yet explored and why?

SLC: I do draw on my life experiences in my work. Not as much as some might think, but a fair amount. I’m sure we all must to an extent. But, admittedly, I’ve happened to have had an interesting life so far, though most of it has been a darker, more difficult, span of time than some others. I was never really very aware my themes tended to be “heavier” than others until readers began making mention of it here and there. I was aware there were good writers and great writers out there who were not writing about the unemployed, single-parenting, divorce, drinking, the confines of religion, and so on. Just as much as I was aware there were writers, like myself, mucking around in those waters and mudholes. I don’t feel so much drawn to write about the subjects I take time to consider long enough for such a thing. I just believe strongly that each person, no matter if they’ve lived next door to one another for fifty years, have their own vital and unique way of seeing each and every thing and person around them.

I’m fascinated by that fact, and even more fascinated and eager to discover what my experiences look, feel, taste, sound like in only the way I can experience them. In order to truly do this, you have to share it with others in whatever you can. It’s funny you should mention if there are any tales I’ve not touched on yet, because there most certainly is, a glaring one, in fact. My maternal grandfather, Bob. He died when I was about four, so never really knew him. I knew he grew up as an orphan and lived by plowing fields for supper and other chores for a bed to sleep in. My family has always said the community raised him. It created in him a strange sense of looking out for himself, much to the hardship of others, especially his wife and children. He exists only in story form to me, and the stories are countless, an absolute well of stories. In all the years I’ve been writing, I only recently started a story based on him. It’s called “The Favor” and should appear in Where Alligators Sleep, if all goes well.

RV: I look forward to reading that story about your grandfather, Sheldon! Let me ask if you ever judge your work, while crafting, or even after a piece has been published? I recently sent off 24 poems to Gloria Mindock at Cervena Barva Press for my upcoming poetry chapbook, Microtones. And right after I clicked the “send” button, I experienced these deep pangs, like she is going to hate them! (good news, apparently she didn’t!) Do you go through this? If so, how?

SLC: I love that you’ve got a chap coming out, hoss. Hats off on that note, and that’s a fine title, too. As for judging my own work, well, you better believe it. Oh, yeah, man. I judge harshly. Old West hard. I can, in all honesty, say I’ve only written five or six stories I knew were good stories at the time I finished them. And like any of us who’ve been working it that long, you’re talking hundreds upon hundreds of stories. Twenty-four years and that’s it. Five or six stories, maybe. Of the two novels I’ve worked out of me like rotted teeth, I threw the first in a creek behind my house, the only copy written on my first typewriter when I was nineteen, and the second, which is good but needs a few major surgeries, remains trunked. It’ll see the light of day, though. As long as I know it’s good, I’ll keep working to see if it can be better. The others, the stories, became tolerable after several drafts, enough drafts that I eventually never wanted to read them again. That’s how it goes, sometimes. Work it until you drop. Somebody will notice. They’ll see how you’ve sweated and heaved and pulled and pushed and never let up. That work will show in your words. And it’ll show if all you did was sit back on your thumb, too.

RV: I thought you were going to say, sit back on your keyster! Hahaha. Okay, I’m going to mix things up now. Time to get off YOUR DUFF, little Joe. Here is a line from a recent Tin House New Voice novel, Glaciers, by Alexis M. Smith: ‘She decided against washing her hands.’ Write a 50 word (or less) piece using any or all of that line. Go!

SLC : Ha! Off my duff I come! Here goes nothing:

“The carpenter held her fingers, the last load of old shingles already hauled off. He stayed on awhile after, picked the yard for torn pieces of the old roof and nails. She sat on the porch while her carpenter softly parted blades of grass. She decided against washing her hands.”

RV: Nice use of white space, very provocative, too. Okay, you’re on an island in the Pacific looking for Amelia Earhart’s remains. Name five different parts of her body and a favorite song you are listening to at the time you discover said part.

SLC: Okay, let’s see here – Crossing a small creek while listening to “Take It On the Chin” by William Elliott Whitmore, I find her jawbone, strong and determined, even in that tiny vein of water. Later, along a ridge north of where we came ashore, I trip across her leg, the boot laces still pulled tightly into an impressive knot. I’m listening to Townes Van Zandt’s “Flying Shoes” while admiring the sturdy boot and the leg that had flown so high for so long. I grow tired after several hours and find a shanty of some sort made of slim branches and great leaves spreading out for a roof.

As I enter, listening to Tom Waits’ “The House Where Nobody Lives,” I find a large stone. Along the side of the stone is a single fingernail seemingly embedded into the rock, seemingly still clutching for purchase. I’m about to heave when I leave the leafy shanty and lose my footing, sliding several yards into a clearing. At my feet I see what at first appears to be a dead animal, its fur matted and clumped. The closer I come to the thing I see its hair, a half inch of her scalp stretching across its underside. The Pixies “Hey” finally rolls through my ears. I can still hear that distinct cry of the guitar as I make it back to the shore line. I’m the first there, so there’s no news to share. I walk the line, listening for the others when a foamy wave moves in over my ankles and then out again. And now she’s looking at me. Those eyes, blinding if stared at for too long, pushed back from the sea and onto the shore of her private and expansive cemetery. And as I look at her eyes, and only her eyes, Hank Williams is there singing “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry.” And I do.

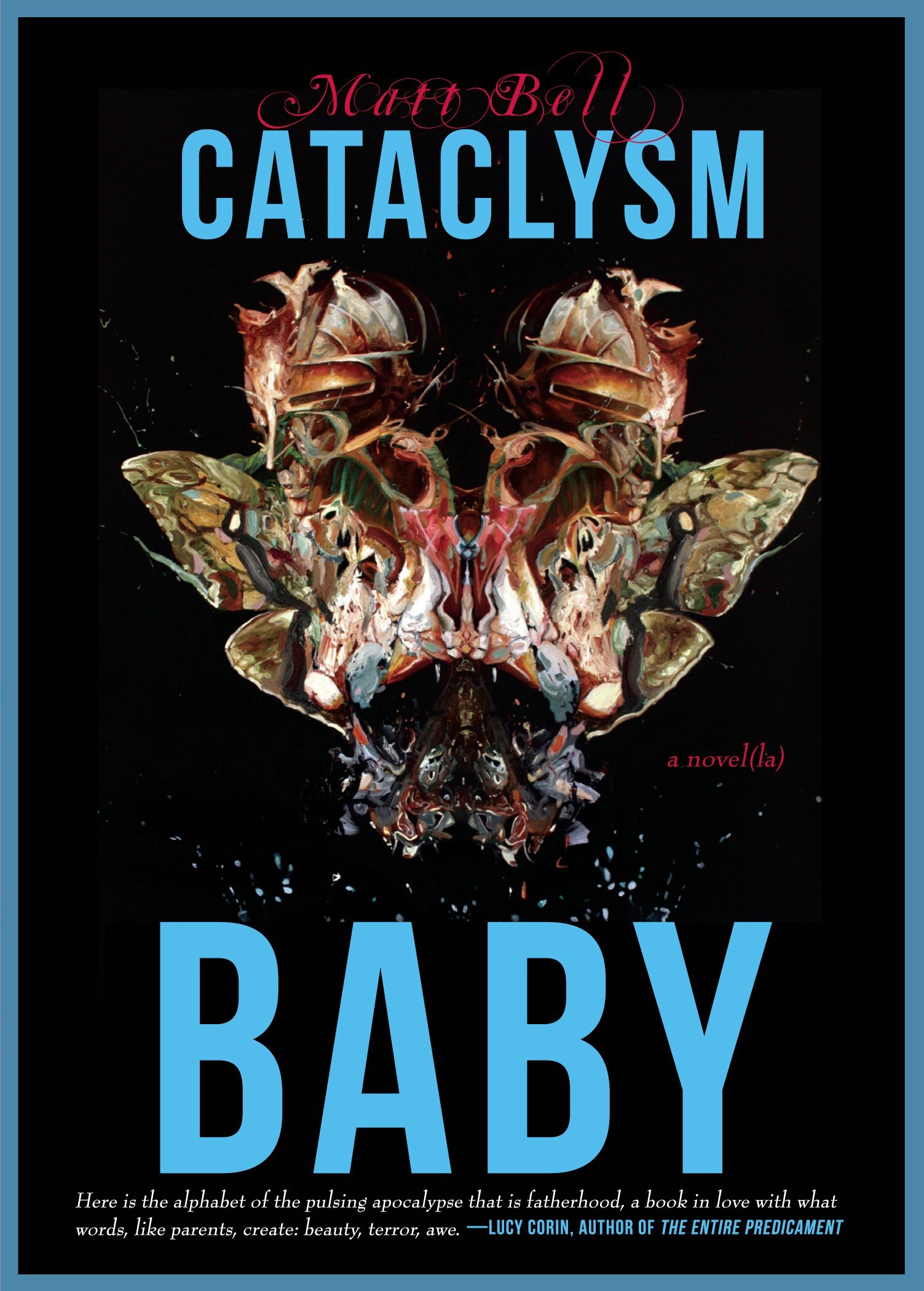

RV: Dang, Little Joe, you’re good. I say, expand and submit that one! Now, I will give you a “word bank,” five from Matt Bell’s new novel, Cataclysm Baby: empty, scars, soot, taste, & swallowing. You can use any or all of them in a 50 words or less piece.

SLC: I’ll tell you something, hoss, those are some fun words to throw together. Here you go: The room is empty as scars without stories when Ben wakes. It is a knocked about box made of soot, and, as he feared, most of the food burned along with all the hope left. Though he cannot taste what is not there, he continues swallowing as if in prayer.

RV: Great imagery there. You’re a natural born poet, my friend. I want to ask you about your online journals. I know you’ve started a few. You took my triptych, “A,B,C” at A-Minor when you were at the helm there. We also cross paths at Fictionaut, a member-only online writer’s community. Tell me how your writing has shifted since the advent and rise of online writing. Any positive or negative influences?

SLC: It was a pleasure to publish “A,B,C”, no doubt. Wonderful work. And, yeah, just realized I tossed in a rhyme without realizing it with the “there” and “prayer”. Well, well. Thanks for suggesting I have a little poetic notion. I think poets are on the front line in the literary world. To write and consider each word, each comma, each line space with such deliberation is something to be admired. To speak directly to your question, man, I cannot overstate how important the online communities of writers and what many consider the indie writing scene have been for me. With each small journal, print or online I either founded or co-founded, I received such satisfaction going through submissions and finding just the right story, the one I just couldn’t wait to read aloud to someone.

With Cellar Door, the first journal I co-founded, we didn’t go online. We paid for a run of two-hundred and fifty copies and sold them from the back seat of our car. We actually stacked the envelopes full of stories in the middle of the living room floor and parted them out into two basically even piles and started reading. That’s where I was first introduced to writers like the late Carol Novack, Matt Bell, and an already well-established Joey Goebel, and many others I never heard from again, but remember their stories as clear today as the second I read the first sentence of their submission. With online journals, I co-founded Wrong Tree Review and then, within the first issue, became interested in starting an online journal that offered readers something new each week. So, A-Minor Magazine came about, which I edited for about a year and stepped aside. I loved the experience, but am not currently involved with any journals. Of late, I’ve been a little selfish. I want to focus on my own work and simply enjoy the work of others. In the past week I’ve added seventy-four books to my wish list at Amazon, not to mention my drop-ins at Fictionaut, the writer’s community you mentioned. There’s always something great to read there. All in all, I would say the positives in the rise of online publishing greatly outweigh any negatives. I think print and online can exist, if not complement the other. People are always eager and pleased to find new options to communicate with each other, share stories.

RV: I like how you’ve worn so many hats leading to this new one: published author (of your new book: The Same Terrible Storm!!!) Explain how this latest transition has changed you, if it has at all. And who are the authors you’ve read lately? Any that stand out?

SLC: Shortly after I learned Foxhead accepted the collection, I made the decision to leave the traditional workforce and write full-time. That has been a major change, and a positive one so far. I’ve been working full-time at this craft since October with the support of my loved ones, and I couldn’t be more fortunate. The true blessing for any writer is to have people on your side who understand that it can be work, not just a hobby. It takes a certain type of person to realize this is a craft, a true pursuit of labor, without actually being a writer themselves. I don’t know if I’d be able to make that leap or not, but I’m thankful to be surrounded by those who can.

The daily grind of writing full-time is a fair amount more challenging than I’d expected, but it’s good work. It helps me to have a few projects going at the same time. Currently, I’m writing the novel and also working on a book of photographs with accompanying flash fiction pieces, each of thousand words, for a future book to be called A Thousand Words. My wonderful lady Heather McCoy is the photographer for the project so we’re getting the chance to work together. The hardest part at this point has been picking my favorites from her portfolio. At one point I had I roughly three hundred pictures sorted out and then realized that would be a pretty huge book at one thousand words each. We’re aiming now for one hundred photographs and stories.

I’ve also been buffering my work day with reading, so I’m glad you asked about what’s off my shelf and beside my laptop these days, Robert. Since I’m in novel mode, I’m reading more along those lines. On tap for now is Ron Rash’s Saints at the River, Tom Franklin’s Crooked Letter, Crooked Letter and a couple story collections with Kyle Minor’s In the Devil’s Territory and Chris Offutt’s Out of the Woods nearby, as well.

How to Save Your Friendships: A Review of Matt Bell's Cataclysm Baby

What keeps Cataclysm Baby from being just another menagerie of impossible disasters are the variations in the fathers themselves, who each struggle to deal with the guilt, anger, pride, and obligation fatherhood brings with it, apart from the apocalypse-fractured world outside the window. Some fathers regard their strange children with single-minded affection, others with scorn. Some sacrifice their mutated children, and some others sacrifice themselves. As the lights go out on the human race, some cling to hope that their children represent some sort of future, while others hold onto only what they can.

You know when someone develops a deep love for a movie, TV show, book, or video game and, before too long, it’s all they’ll talk about? Or how repugnant your sister is in the first few weeks of her new romance? We, as humans, are compelled to express our deep love for things, a habit which will murder your relationships unless you find people who love the same things you do (the reason people who like weird stuff like dubstep and electrocution tend to gather together).

This isn’t really a recommendation that you buy this book. Matt Bell’s name on the cover should be all the incentive you need to do that. But when you buy Matt Bell’s Cataclysm Baby, which you absolutely should, I’d recommend you buy at least a dozen copies, or one for each friend and family member you’d miss when they get tired of you obsessively talking about this book and stop returning your calls. Supplying all your loved ones with copies is an invitation into your new-found pleasure and will hopefully keep them from having sudden emergencies just as you arrive and staging interventions.

And talk about this book you will. You’ll talk about Bell’s prose, some of his finest yet, which has something of the biblical in it, something of the prophecy. About how you can imagine these stories told in dusty, burned-out rooms by grizzled fathers with thousand-yard stares sliding down the other side of survival. You’ll talk about this passage, and dozens more like it:

The day [my son] turns thirteen, he tells me I will wait three more months before I sneak into his room and read his diary, and that by then it will be too late.

He says, I know you could save us if you read it today, but I know you won’t.

You’ll talk about the references, the intelligent re-workings of Greek mythologies, Arthurian legends, and biblical stories. The Sirens make an appearance as three daughter mimics, luring villagers out into the floods destroying their world. A man, driven by the ghosts of his daughters, builds tower after tower, not to get closer to God, but to find the voice of his wife. A tanker carrying the world’s last women floats off the West coast, waiting for the world to be clean enough to deserve their return. A man chooses his own calf-child for sacrifice in a lottery. Bell’s handling of the sources is elegant, keeping to the core of what the stories are about, and might provide enough conversation material to ensure that your favorite barista will never ask how your day is going again.

You will probably, more than anything else, talk most about the endless variety Bell achieves, despite adhering to a restrictive formula. In almost every story, children are born deformed, mutated, something other, into a drying out or burning or drowning world. Of course, Bell shows off his impressive imaginative range with the “wrong-born” infants: some only balls of fur, some born as only invisible puffs of air.

What keeps Cataclysm Baby from being just another menagerie of impossible disasters are the variations in the fathers themselves, who each struggle to deal with the guilt, anger, pride, and obligation fatherhood brings with it, apart from the apocalypse-fractured world outside the window. Some fathers regard their strange children with single-minded affection, others with scorn. Some sacrifice their mutated children, and some others sacrifice themselves. As the lights go out on the human race, some cling to hope that their children represent some sort of future, while others hold onto only what they can. The family dramas, the reality of the fathers in these stories trying to hold onto a world that inexorably spins away, keep these stories from being just another meditation on the ways the world could end.

And the end. You will talk about the ending, the last chapter.

Obviously, this is the kind of book that can leave a reader sitting by himself on the bus, other passengers clutching purses and children while he mutters under his breath about how no one reads great books anymore. You don’t want to be that guy, so get a dozen copies. More if you actually like your family.