To Shoehorn a Cat: A Conversation with Reese Conner

The dying or death of a cat allowed for a general exploration of grief, yes, but it also led to questions about what we are allowed to grieve, how much we are allowed to grieve, and who is allowed to grieve.

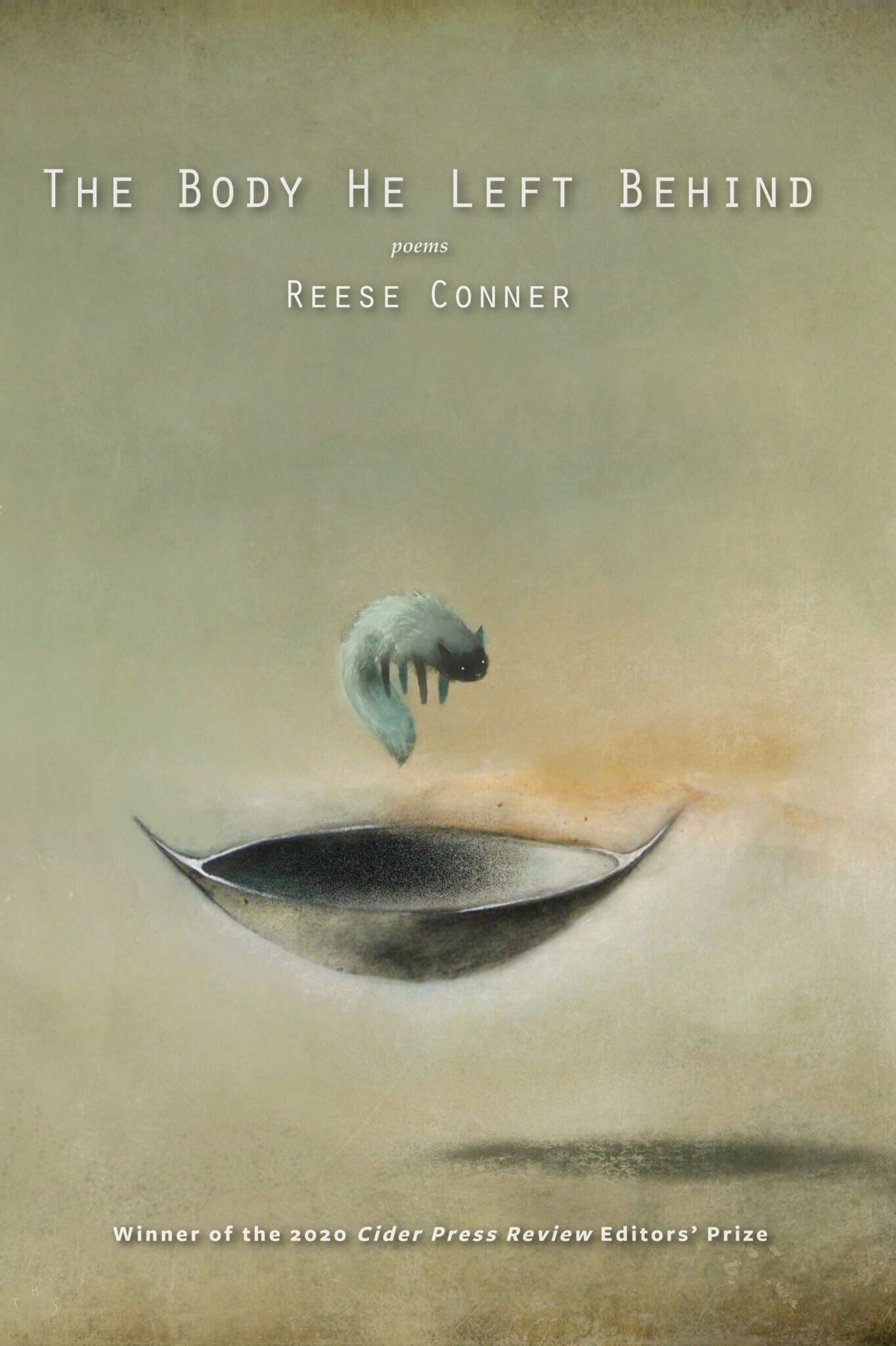

Reese Conner is a poet, teacher, and winner of the 2020 Cider Press Editors’ Prize Book Award for his debut poetry book, The Body He Left Behind. His work has appeared in Tin House, The Missouri Review, Ninth Letter, Barrelhouse, New Ohio Review, and elsewhere. His writing has received the Turner Prize from the Academy of American Poets and the Mabelle A. Lyon Poetry Award, and he has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Reese teaches composition and poetry workshops at Arizona State University.

I first met Reese in 2012 in Tempe, Arizona, where we were both incoming MFA Creative Writing students at Arizona State University. In the years since, I’ve been fortunate enough to have Reese, not only as a peer, but as a trivia teammate, Dungeons and Dragons comrade, and breakfast buddy. It has been a pleasure to see Reese grow as a poet in the time I’ve known him, to see his work become more biting, more introspective. I admire Reese’s ability to mix humor and earnestness, for his ability to look at what others want to turn away from. You can preorder The Body He Left Behind, a heartbreaking book of poems about cats, grief, and the ways we love, from Cider Press or your local bookstore.

*

Dana Diehl: We’ll start at the obvious place. What, for you, makes a cat such an enticing subject for a poem?

Reese Conner: Firstly, and I cannot stress this enough, I actually like cats. Let me tell you, actually liking cats did some hefty lifting when it came to writing a book chiefly about cats. The truth is I struggle mightily to simply start writing a poem, which I understand is a common issue for writers, so I don’t imagine myself unique. One way I found to combat that looming failure-to-launch was to shoehorn a cat into every piece I could because it created an immediate investment for me — I cared about the cat, so it made it easier for me to imagine the reader caring for the cat, too. That, in turn, made it easier for me to imagine the poem being successful and, therefore, worth writing.

Secondly, cats acted as vehicle to tackle some pretty big abstractions. For example, I was particularly interested in the ways we prepare for, encounter, and react to grief. The dying or death of a cat allowed for a general exploration of grief, yes, but it also led to questions about what we are allowed to grieve, how much we are allowed to grieve, and who is allowed to grieve. In one poem, “The Necessary,” I make this quite explicit by ranking griefs in order of importance. The point is not that an objective measurement of griefs coming from an external source is actually valuable, rather the point is that the ranking of griefs is a powerful, tacit thing that we already do. And that becomes wildly hurtful when one’s internal, subjective measurement of a grief does not align with where others think it ought to be. In particular, this comes into play with the father in the poems, who deeply loves his cat but does not feel comfortable mourning a cat on account of traditional masculinity. Come to think of it, exploring the effects of masculinity by way of a beloved cat is essentially the SparkNotes of my book. Even though I gave you the SparkNotes, I still hope you read it, though!

DD: I think there’s this fear that in writing about pets we risk being “cheesy” or overly sentimental. Is this something you actively tried to avoid while writing these poems? Or were there other challenges you felt you faced?

RC: Hmm…this is a really good question. I was certainly aware of the risk of sentimentality because I had been warned, but I guess I never really worried about it. In fact, I like to think that I purposefully approached the sentimental because, while it is often regarded as “cheesy” and lowbrow and not appropriate in a poem, there is a reason it is so ubiquitous, right? It speaks to shared experience. It must. We have Hallmark cards and abstractions because they resonate with just about everyone. And so, since the collective “we” has a penchant for getting overly sentimental about our pets, it seems pretty valuable to explore why. Pushing that further, it seems pretty valuable to explore why it is considered overly sentimental do so, especially if it is so common. Why is it that there is a perception that dead or dying pets should not be worth the grief we give them? I’ve certainly felt it — there is a guilt associated with mourning a pet so powerfully, and, in my experience, that guilt is a reaction to the idea that it is just a cat or just a dog, again referencing that unspoken hierarchy of griefs. In my book, I guess I wanted to legitimize mourning a pet so powerfully by exploring why the sentimentality makes sense and why we shouldn’t look down on it.

DD: Please tell us about the process of writing this collection. At what point did you know you had a book on your hands?

RC: I want to preface by making clear that I do not necessarily suggest the route I took because much of it was flailing about and generally having no idea about a great many things regarding publishing.

All right, so the one talent I know I have when it comes to writing is my ability to get lost in the weeds. I am consistently proud of my moment-to-moment choices within poems. You know, diction, line breaks, the particular idea I am trying to get at, etcetera? I’m proud of those. I really pay mind to have a rationale for each of those smaller choices in case the never-going-to-happen scenario of someone publicly holding me accountable for one such choice actually happens. This means that I am pretty confident in each poem I have written because I have the bandwidth to consider a full poem at a time. Unfortunately, that talent for the microscopic seems to have adversely affected my ability to see the big picture, which made organizing all my poems into a cohesive book quite the task.

And so, my process was mostly to lean into my talent and simply focus on each poem as a standalone. There was additional logic behind this approach because the idea of ever winning a book prize and publishing a book felt impossible, so it made sense to devote my attention to publishing individual poems. I didn’t really realize I had a book until I had enough poems to make a book. At that point, I took stock of what I was actually doing in my work as a whole.

All right, to be fair to myself, I may be being a bit misleading about how little I considered a book-length work. It’s not that I had never considered what my book might look like. For example, I knew, even as I was writing standalone poems, that fathers and cats and domesticity were through-lines for my work. I also knew exactly what the first and last poems in my book would be, and I knew the important poems that needed to go in-between in order to make the narrative work, but I had the vaguest idea of where those poems belonged. Essentially, I felt overwhelmed. When I had enough poems to meet book-prize criteria, I slapped together an iteration of my book that was significantly longer and less cohesive than what it is now. It also had a different title that I consider embarrassingly pretentious in hindsight: An Expectation of Broken Things.

Anyways, at this point, a wonderful friend and fellow writer, Melissa Goodrich, offered to slog through my mess and to help me out. I owe an incredible debt to her suggestions on ordering, cutting, and even the title of the book. Truly, I cannot overstate how integral Melissa’s involvement was in making my book what it is. You should absolutely check out her fiction and poetry because she’s not just an organizing maestro, she’s a damn good writer, too. When I read through my book as assembled by Melissa, I knew I had something to be proud of (and I knew I had someone to thank).

DD: In the first section of the book, there’s a focus on the physicality of the cat: old cat made of bird bone and balsa, broken rubber bands / heavy as ball bearings. However, as the book goes along, there’s a shift to the human body, as well. How are the body of the cat and the body of the boy connected for you?

RC: I guess those specific bodies are not terribly connected for me. Bodies, in general, were an important topic in the book, though. I wanted to really wrestle with the distinction (or lack thereof) between the body and the mind, which I know sounds like pseudo-philosophical bullshit, so we can roll our eyes together. Still, I recall a time when I was young where I honestly did not consider the two things as separate. That has changed. Now, when I define “me,” I am thinking of my mind primarily. And so, I am very interested in locating that last time when I hadn’t separated the two, when my body was “me” as much as anything else. Exploring that transition as well as exploring how we often define others as their bodies rather than their minds were important considerations when writing my book.

DD: This book takes a stark look at violence, as it is inflicted both by and on the subjects of these poems. The speaker loves his cats, while simultaneously observing their potential for brutality, their propensity to kill. The speaker begins to see violence in himself, as well.

I love this line from “I Was Innocent After All”: She told me / I had been good incorrectly […]

And this one, from “The Necessary”: To be clear, he is not a monster. / He simply decided that progress / meant putting things / where they do not belong […]

What do cats, or other animals, teach us about being a monster versus being innocent? Is it possible to be both at once?

RC: I think animals can teach us quite a bit about both monstrousness and innocence, particularly regarding the nuance of intentions mattering while concurrently not mattering at all. For example, in my poem “Like a Gift,” I address this head-on when the speaker is holding his cat to protect it from the neighbor’s dog. The cat recognizes the danger that the dog poses and would likely prefer to run away, so being arrested in the speaker’s arms probably doesn’t sit too well with the cat. And so, the poem posits that at some point the cat’s instinct to run from the dog becomes an instinct to run from the speaker, as well. This, in turn, poses the question of whether the speaker is correct to “save” the cat from its own instincts simply because the speaker has good intentions and the power to impose them. If the answer to that question seems simple and that the speaker was wholly in the right, then I would offer another set of questions regarding at what point the cat loses enough agency for the loss of agency to matter; at what point micromanaging the cat’s instinct becomes a trespass; and at what point the intention to save the cat from itself becomes monstrous. Obviously, I do not think there is an easy, blanket answer to these questions, which is why I do not offer one in the poem and why I won’t offer one here. What I do know is that many people seem to think good intentions earn a clear conscience, end stop. I believe that mindset can be incredibly dangerous and is often incredibly condescending, which is why it is something I address pretty heavily in my book.

DD: What are some other obsessions in your life right now? Do you find that they influence or inform your writing in any way?

RC: This is not a “right now” thing, but I have been obsessed with movies, television, and music for as long as I can remember. Each influences and informs my writing in powerful ways. In fact, I would say that my primary mode of experiencing stories is not through traditional reading but through those other modalities. I used to be pretty self-conscious about that because I felt like I couldn’t be a strong writer if reading traditional texts wasn’t my main source of reading. I do not think this is as widespread as it once was, but there is often an elitism when it comes to types of writing and, therefore, types of reading. I wholeheartedly disagree with it, but I’m sure you’ve heard this mantra: “Those who can’t write poetry, write short stories. Those who can’t write short stories, write novels. Those who can’t write novels, write screenplays.” I have heard that exact quote in multiple workshops throughout my career as a writer, and it always stung. I get it, though. Follow that proposed escalation in quality of writing and you essentially find the converse of who makes the most money from writing. Considering that, I can understand why some would want to believe in that hierarchy. After all, you’re not going to make much money from poetry, so it would be nice to believe that it is the purist expression of the lot. So, while I understand where the cliché comes from, I adamantly disagree with it and, more than that, think its utter bullshit. Good writing is good writing.

On a lighter note, I will offer one movie, television show, and song that helped inform some part of my book.

Movie: In Bruges.

Television show: Dollhouse.

Song: “Night Moves” by Bob Seger.

DD: If The Body He Left Behind had a soundtrack, what are a few songs that would be on that list?

RC: “Independence Day” by Bruce Springsteen. “As the World Caves In” by Matt Maltese. “Father and Son” by Yusuf / Cat Stevens. “Prison Trilogy (Billy Rose)” by Joan Baez. “Cat’s in the Cradle” by Harry Chapin. “Divorce Song” by Liz Phair.

DD: Finally, what advice do you have for emerging poets trying to finish or publish their first books?

RC: Well, I’m not sure if I have any advice on how to finish a first book other than to write it in a way that works for you and to take every bit of advice on how to write a book with just the biggest grain of salt. There are so many “truths” about what you need to do in order to be a writer and, while I think most of them are well-intentioned, they often serve to gatekeep who gets to be a “real” writer. As a wise interviewee once said: good writing is good writing.

As for publishing a first book, I do have some advice, and you may take it with whatever sized grain of salt you see fit: submit. Honestly, that’s it. I know so many ridiculously-talented writers who are too intimidated to submit, too afraid of rejection to submit, or who just don’t quite believe the mountain of failure that happens behind the scenes for just about every successful writer. If you are an emerging writer and you have conviction in your work, submit more than you think is necessary because that is what’s necessary. Get as comfortable as you can with rejection because, unfortunately, what you’ve heard is true: publishing is a numbers game.

Lastly, and this has nothing to do with finishing your own book or publishing your own book, but I’m going rouge with some unrelated advice: urge your own ridiculously-talented writer friends to submit, too. Be the good kind of envious when they succeed and support them as fully as they deserve.

Sense of the Strange: An Interview with Chloe N. Clark

In Chloe Clark’s new short story collection, Collective Gravities, published with Word West, she takes us to the stars. She takes us to the zombie apocalypse and to mysterious research facilities. She frequently bends genre, putting horror side to side with sci-fi.

Chloe N. Clark holds an MFA in Creative Writing & Environment. Her chapbook, The Science of Unvanishing Objects, was published by Finishing Line Press and her debut full length poetry collection, Your Strange Fortune, was published by Vegetarian Alcoholic Press. Her poetry chapbook, Under My Tongue, was published with Louisiana Literature Press in early 2020. She is founding co-editor-in-chief of Cotton Xenomorph. She teaches multimodal composition, communication, and creative writing. Her poetry and fiction have appeared such places as Apex, Bombay Gin, Drunken Boat, Gamut, Hobart, Uncanny, and more.

In Chloe Clark’s new short story collection, Collective Gravities, published with Word West, she takes us to the stars. She takes us to the zombie apocalypse and to mysterious research facilities. She frequently bends genre, putting horror side to side with sci-fi. It was a true joy to read Chloe Clark’s new collection, and I was privileged enough to have the opportunity to chat with her about the process of writing the book.

*

Dana Diehl: Please tell us a little bit about how this book came to be.

Chloe Clark: On one level, there’s the simple answer: I had a lot of stories and wanted to collect them up. On the truer level though, I kept finding that I’d circle back to similar themes and ideas, often seeing them in different ways, throughout the course of my writing and so I began to see a collection taking shape based on those qualities.

This collection spans ten years of writing: the oldest story in the collection was originally drafted while I was still an undergrad. Which is weird to think about because I now teaching writing to undergrads. So the stories in this piece have gone through a big, important chunk of my life.

DD: I see images repeat themselves in several your stories. The image of the bruised woman. Space travel. Mysterious illnesses. The images have different significance in each story. It was fun for me as a reader, because I felt like I was seeing alternate realities play out. It was also fun looking for the ideas that strung your stories together. How intentional were the similarities between your stories? How do you think reoccurring images might strengthen a collection?

CC: Often the similarities were very intentional, in my mind a lot of my stories exist within the same universe (or slightly altered versions of it). I’ve always loved writers whose work invites conversation between pieces (it’s a bonus for people “in the know” who have read the other stories and see the connections, and it also feels like a reader can see the world of the stories more fully). Sometimes, they were less intentional when I was writing the stories, but then when editing I’d see that I’d done it and it was because I had felt that the stories shared some connection.

I’m a huge proponent of novel-in-stories, so I think that continuity strengthens and redefines the way we read the pieces when we notice the connections or when we go back for a reread. They feel somehow “truer” when there are those connections that help us see the story beyond just the one frame.

DD: Another prevalent theme I see in your stories is isolation. One of your stories, “Bound,” explores a plague that sweeps the planet and forces the speaker into isolation. As we do this interview, we’re approaching the third month of quarantine in the US. When I read “Bound,” I found it to have chilling similarities to what we are experiencing today. Have recent events changed the way you view these stories? Has quarantine changed the creative work you’re doing now?

CC: This is a multilayered question to me. I’ve always been fascinated by isolation and how it affects people. Many of my favorite writing and movies, growing up, dealt with this. In some ways, I think isolation is one of the ultimate human fears.

I think recent events have, if anything, made me feel more strongly about the need to deal with isolation in writing. I think voicing the fears and anxieties of isolation, for people, is important. Writing and reading help us feel less alone.

DD: So many of these stories take us into the stars. What draws you to outer space as a setting for your stories?

I’m not sure I have a great answer for this. For as long as I can remember, I’ve loved space. The unknown and the thought of all that exploration that has yet to be done is so compelling. Plus, what has been discovered through the reach for space has been so important and profound.

In my heart, I’m a wanderer and what better to go towards than the stars?

DD: Is there a movie or novel that has especially fueled or inspired your interest in space?

CC: Oof, that’s hard to narrow down. But I think the main media of my childhood were three distinct space pieces of art: Ray Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles, the BBC radio production of Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, and the film Aliens. I think that mix actually kind of perfectly sums up my writing about space: A lot of hope and exploration, a distinct sense of delight, and a dose of fearing the unknown.

DD: In Collective Gravities, you explore a huge range of genres, from realistic fiction to science fiction, horror, and even zombie apocalypse. What do you like about playing with speculative fiction? What genres are your favorite to consume in your everyday life?

CC: I think I think in multiple genres. It’s very hard for me to stick in one, even within the scope of a single piece. I’ve said before that I think speculative is how we live our lives—everyone has a sense of the strange about how they view the world and it makes sense to imbue our stories with that, too.

I read pretty widely. I’ve always had a love of sci-fi and horror, but I also read tons of domestic fiction and literary fiction. My favorite writers tend to be the ones who have feet in every genre like Colson Whitehead, Helen Oyeyemi, and China Mieville.

DD: In your bio, you mention that you have an MFA in Creative Writing & Environment, which is a degree I didn’t even know existed! What is your relationship with the environment and space as you’re working through a story?

CC: It’s a very cool and unique degree, from Iowa State University, that I wish more people knew about!

I think environment is extremely important to every piece I write—because environment encompasses so much: it might be a small town, but it also applies to the reaches of outer space or a haunted apartment building. Place influences character and story as much as any other element.

We all have places that center us—be it our homes or a spot that makes us feel something. And I think that’s true of most good works of fiction too—there’s some distinct sense of place that makes the reader understand or feel the piece in a way.

Because I’m a very visual writer, I usually know exactly what a story’s environment looks like. But I also hate describing that stuff in too much depth—because I want the reader to have input in the place they conjure up as they read. So one thing I always try to be cognizant of is finding the key detail that brings me into an environment and that’s what I’ll include. Sometimes I know that key detail right away, but it’s often one I eventually find in revision and pull into the forefront as I strip the other details away.

DD: One of my favorite lines in this collection can be found in “The Collective Gravity of Stars”:

“’Well, everything will be better now,’ her mother said. Callie wondered if anyone had ever said that and watched it come true.”

For me, this line captures the way your stories seem to pendulum-swing between pessimism and optimism. However, they tend to more often than not end in a moment of hopefulness, of light. Can you speak to this

CC: I often describe myself as an optimistic pessimist. I think there’s a lot of importance to knowing and understanding how much is flawed and terrible about this world. But hope is equally as important, because that’s what helps us strive to actually make change.

And from a storytelling perspective, I think pessimism has its place, but it’s a lazy device. Hope is an active choice to be made and that’s far more exciting to me.

DD: If you could take off into outer space with your characters, where would you most like to go?

CC: Honestly, I’d be overjoyed just to go to space at all. But if I had the means to go anywhere, I think Mars would be a good start. There’s such a build up of Mars in my head from all of the sci-fi of my youth that imagining feeling the ground of Mars beneath my feet would be as close to living inside my dreams as I could get.

The Real United States: A Conversation with Matthew Baker

In this interview, Matthew Baker discusses writing high-concept narratives, how speculative fiction can allow us to grapple with controversial topics more genuinely, and the films that inspire his writing.

Named one of Variety’s “10 Storytellers To Watch,” Matthew Baker is the author of the story collections Why Visit America and Hybrid Creatures and the children’s novel Key Of X, originally published as If You Find This. His stories have appeared in publications such as The Paris Review, American Short Fiction, One Story, Electric Literature, and Conjunctions, and in anthologies including Best Of The Net and Best Small Fictions. A recipient of grants and fellowships from the Fulbright Commission, the MacDowell Colony, the Ucross Foundation, the Ragdale Foundation, Vermont Studio Center, Virginia Center For The Creative Arts, Blue Mountain Center, Prairie Center Of The Arts, Djerassi Resident Artists Program, the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, and the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, he has an MFA from Vanderbilt University, where he was the founding editor of Nashville Review. His other projects include Early Work. Born in the Great Lakes region of the United States, he currently lives in New York City.

I’ve been a fan of Matthew Baker’s work since 2013, when, as an editor for Hayden’s Ferry Review, I was introduced to his story, “Goods.” A year later, the journal published another of his stories, “Html,” a story partially written in code.

When I read “Goods” for the first time, I was a first-year MFA student, writing a series of unsuccessful stories and struggling to figure out what kind of writer I wanted to be or could be. Baker’s stories were playful and idea-driven, but simultaneously had heart, had the ability to move me. He provided me with an example of the sort of writing I might want to do.

I jumped at the opportunity to read Baker’s new collection, Why Visit America, forthcoming in August, and I was not disappointed. The stories he tells are funny and heartbreaking and familiar and surprising all at once. In this interview, Baker discusses writing high-concept narratives, how speculative fiction can allow us to grapple with controversial topics more genuinely, and the films that inspire his writing.

*

Dana Diehl: Many of your stories seem to be driven by “What if…?” questions. What if men became obsolete? What if children were raised by the government instead of parents? What if people could become data? I love how deliciously high-concept this collection is. Did all of your stories begin with a concept? Did any of them begin instead with a character or image, for example?

Matthew Baker: I’m embarrassed to say that every story began with a concept. The book itself began with a concept: thirteen parallel-universe stories (one for every stripe in the flag) that would span all fifty states of the country, and that together would create a composite portrait of the real United States: a Through The Looking-Glass reflection of who we are as a country.

I once submitted a story to a prestigious literary magazine, and the editor rejected the story with a note that said: “too high-concept for us.” For a writer like me, what that note actually said was: “don’t submit to us again.” I can only do high-concept.

DD: What was it like to write a short story collection with an overarching concept already in mind? Did it make it easier? Did it ever feel restrictive?

MB: It was a tremendous challenge. I loved that about it though. That was what made the writing fun.

DD: Despite these stories being very high-concept, they are also movingly character-driven, grounded in an individual human experience. Do you think character is key to writing narratives that move beyond a concept and become stories? What advice do you have for writers working in a similar genre, who struggle to move beyond their initial concept and develop character or find their inciting incident?

MB: I think about storytelling less in terms of “plot” and “character” and more in terms of “idea” and “emotion.” Strategically, I don’t approach a story thinking “how can I develop a plot?” or “how should I develop this character?” I approach a story thinking, “Given this premise, what combination of events and desires will maximize its emotional impact?” In my experience the nature of the work becomes very clear very quickly when plot and character are viewed as ingredients in an emotional reaction in the reader, rather than simply as necessary elements of a story.

DD: Was there a story in this collection that especially challenged you? What do you do when the right ingredients are difficult to find?

MB: “To Be Read Backward” was the greatest challenge conceptually—trying to imagine the physics of that universe accurately, and to be consistent in how the narrator uses language, especially verbs, to describe the events of the story. But the story that was the greatest challenge narratively was “Testimony Of Your Majesty.” I wrote about half of the story and then got stuck. I knew the emotional reactions that I wanted to synthesize, and I had assembled some reliable ingredients, but I still couldn’t quite figure out how to achieve what I wanted. I set the story aside for a couple of years, came back to the story, struggled with the story, set the story aside again, came back to the story, struggled with the story, set the story aside again. That was the process. Years of failed experiments. That story was a work in progress from 2013 through 2018.

DD: Were there any concepts or ideas or stories or experiments written for this collection that ultimately didn’t make it in?

MB: There were a number of concepts that didn’t work on the page. And there’s one story that I actually completed and even published—a story called “The Eulogist” that appeared in New England Review in 2012—that I was still planning on including in the collection as late as 2018. Ultimately, though, I decided the story was just too rudimentary and clumsy. Also, I wanted the collection to have a neutral emotional pH—there could be stories that were depressing and there could be stories that were uplifting, but I didn’t want the collection overall to register as depressing or uplifting—and “The Eulogist” would have given the collection an overall unneutral pH. So that story got replaced by “The Sponsor.”

DD: The issues tackled in these stories are painfully familiar. You explore violence against women, parents struggling to accept their transitioning child, and flaws within the justice system, just to name a few. But by placing these issues within parallel universes or dystopian (or utopian) futures, you allow readers to see them with new eyes. Why do you prefer speculative fiction for these stories instead of straight realism?

MB: In any human society, having a constructive conversation about social or political issues can be difficult, and we live in a country so radically polarized that at times it seems to be on the verge of a civil war. If you try to have a conversation with somebody about a topic like climate change or gun control, immediately these walls come up, these psychological barriers as thick as brick. It’s become impossible to talk about anything important. There’s no way to do it—unless you disguise what you want to talk about, cloak the topic in a seemingly harmless form. I turned to speculative fiction in hopes of giving readers a space to genuinely grapple with the ideas behind these issues and to genuinely access the emotions involved.

DD: If you had to live inside one of these futures you’ve imagined, which one would it be? Why?

MB: “A Bad Day In Utopia.” I wouldn’t mind having to live in a menagerie, and I honestly do think the world would be noticeably improved.

DD: How would you spend your time in this hypothetical menagerie?

MB: Probably reading, writing, napping, and trying to convince the guards to play chess with me.

DD: You’ve also written a really wonderful children’s book titled If You Find This. Can you talk about the experience of writing this novel and how it differed from your experience writing short stories for adults? Were the experiences surprisingly similar in any ways?

MB: Well, If You Find This was also high-concept: a children’s novel narrated partly in music dynamics and math notations. And like Why Visit America, If You Find This is a book that’s about place. It’s a Michigan novel, a Great Lakes novel. But If You Find This was also a very personal book for me. It’s not autobiographical, but in that book I was writing about my childhood and about my family and about my friends back home. Why Visit America is different in that I wasn’t writing about my own life in any of the stories in this book. In Why Visit America, what’s personal are the issues.

DD: Who or what are your inspirations outside of the literary world? Are there any filmmakers or artists or musicians who influenced the stories in this collection?

MB: The films Her and Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind had a tremendous influence on the book, as models of emotionally rich sci-fi. The anime Sword Art Online, which for me was a master class on sincerity and vulnerability and the virtues of sentimentality. The video games BioShock and BioShock Infinite, which deliver social and political commentary with such supreme grace and skill.

But—I hadn’t thought of this until just now—maybe the biggest influence was an old VHS tape that I discovered at my father’s house when I was a child. Written on the tape in my father’s handwriting were two words: “The Wall.” I distinctly remember watching that tape later that afternoon, alone in the basement, lying on the carpet, gazing up at an old cathode-ray television. It was Pink Floyd — The Wall, the film adaptation of the rock opera by Pink Floyd. Seeing it was a revelation for me. I hadn’t realized until that moment that a music album could be more than a collection of random songs—that together the songs could tell some larger story. From the beginning I’ve thought of Why Visit America as a concept album, and that old VHS tape is what taught me what a concept album is.

DD: Is there a short story collection that you feel like does this especially well?

MB: Primo Levi’s The Periodic Table, although that’s composed primarily of nonfiction. And Italo Calvino’s Cosmicomics, along with Invisible Cities, although that’s technically considered a novel. I especially adore The Periodic Table.

DD: Who should read Why Visit America? Who is your ideal reader?

MB: All true Americans.

I Know I’m Somewhere New: An Interview with Chelsea Biondolillo

Practically, I live with a lot of anxiety and attendant depression, and birds are one way for my brain to get some perspective. It doesn’t always work, but sometimes looking for a bird can help me to break out of panic states.

Dana Diehl: In this book, you use birds to reflect on your life. Why do you think birds have such power over you? Why do you think they illuminate your life more effectively than other animals might?

Chelsea Biondolillo: Birds live on every continent. They have incredible diversity of size, shape, color, and behaviors. When I travel, birds are one way I know I’m somewhere new (mockingbirds in Arizona, scrub jays in Oregon, rheas in Chile, tuis in New Zealand, and European cuckoos in Austria). And while they are unlike people in nearly every way, they feature frequently in our metaphors and clichés across cultures and throughout history. This means they can always be found somewhere in the periphery of any story I want to tell.

Practically, I live with a lot of anxiety and attendant depression, and birds are one way for my brain to get some perspective. They remind me about all I can’t know and can’t control, about all the things I can’t see (like geomagnetic navigational lines) and will probably never understand (like why Oregon has a hummingbird that doesn’t migrate). It doesn’t always work, but sometimes looking for a bird can help me to break out of panic states.

DD: As long as I’ve known your writing—about five years now—you’ve been writing about and researching birds. It makes me wonder, which came first? The birds or the writing? Did these passions develop independently of each other, or have they always been intertwined? Or has one fed the other?

CC: I started actively writing after I lost my corporate job in 2008, and my first publications came the following year—short travel essays on a couple of blogs, some sidebar pieces for glossy mags, and a handful of book reviews. One of my first essays published in a real literary magazine, though, was about starlings. It was the runner up in Diagram’s hybrid essay contest in 2011. That same year, according to my Submittable rejection history, I was sending out a piece on red-winged blackbirds (which eventually appeared in Birding in 2014) and one on hummingbirds (landed in Phoebe, 2012). I remember printing a bunch of peer-reviewed papers on big cats when I got to grad school in 2011, because I wasn’t sure I wanted to be the bird lady, but nothing has so far come of those. My thesis was full of birds and I still like writing about them.

My grandmother was an avid birder, and much of my reading and creative pursuits were encouraged by her—so I think there’s some creative-muscle memory there, but also there’s a lot of science available about birds, and so when I had a bird question (like, why do starlings mimic, or are hummingbirds really headed toward extinction), there was easy information to find and mostly approachable experts to interrogate. In that sense, birds helped me become a more interesting writer.

DD: The essays in this book vary widely in form. What do you enjoy, or what is useful, about shifting forms?

CB: My undergraduate degree is in photography, but that’s only because my alma mater hadn’t yet created a mixed media studio major. In art school, I sewed books and glued tiny tarot cards on the pages. I built boxes and filled them with broken ceramics. I took photos and transferred them to watercolor paper. I was always looking for my form—and it turns out it was in a different discipline! Playing with text and form in my essays is one way I am continuing that collage/mixed media process. Experimenting with line breaks or balancing small text blocks with images (or obscuring text with photos) allows me to view an essay as a visual composition or even as an object—which means I can consider how I hope to reach a reader and a viewer, both.

DD: In “The Story You Never Tell,” fifteen lovely, stark, black-and-white photographs of seashells block out fifteen pages of text. The words that creep around the edges of the photographs are ominous and evocative. What was it like to write this piece? Did you know you’d cover it up as you wrote it? If so, how did that affect the experience of writing it?

CB: That essay was originally written as a “regular” essay, but after a few rounds of revision, it still didn’t feel done. I wanted a way to redact the textual specificity without turning it into a MadLib that readers would want to solve like a puzzle. As an art student, I often incorporated words, phrases, or even pages of text in my work, and as a result, had many conversations with my instructors about how readability can negatively impact a composition. (Reading the text was not supposed to be the point in painting class.) I wanted to play with that idea—how much text would it take to make clear that what the viewer was seeing was an essay, without the content of the essay taking over? I was inspired by works from painter Titus Kaphar and texts like Salvador Plascencia’s The People of Paper, which feature elements of concealment / or otherwise hiding one or more parts of a composition to highlight another. I tried out several methods of obscuring the text, including other imagery, before settling on portraits of seashells from both my and my grandmother’s shell collections.

And while the resulting piece can’t be “solved” through reading (so it’s not like I can spoil it), I am worried that too much talk about the hows/whys of writing it could dictate a new reader’s experience of it in ways that I want to avoid. In that regard, it could be sort of a spoiler to say too much more about it.

DD: You mention several animals that have occupied your life: the cats, the geese, the insects, the dogs, the mockingbirds. Who are the important animals if your life right now, both wild and domestic?

CB: I’m living in the home my grandparents built, and one of the artifacts my grandmother left behind was a stack of birding journals. Over several years she tracked every bird she saw every day—most from her own picture window. It’s been weird and amazing to read her journal and see which birds are still regularly appearing at the feeders my partner puts out, and which seem rare now. We delight in seeing downy woodpeckers and varied thrushes, and often see bald eagles in the neighborhood—something I do not remember from my childhood.

As far as non-bird obsessions go, the other inhabitants of this place, the rabbits, snakes, deer, and hordes of ravenous insects (they got about half of my kitchen garden last year and would love back into our house’s fir posts and beams) and their boom-bust seasonal cycles are one of my areas of focus right now, for both practical and creative reasons. But also, I’ve also become much more aware of plants, as I’m currently surrounded by two acres of formerly neglected landscape. What thrives on neglect, and what literally withers and dies without care is of considerable interest to my gardening decisions.

DD: If you could disappear off the grid for a year and immerse yourself in the study of a single species that you haven’t already devoted a lot of time to, where would you go? What would you study?

CB: Being back on the West Coast has reminded me how much I love the Pacific. Rather than any single species, I’m often interested in systems, and the relationship between sea lions, salmon, and fishermen out here (and its current lack of balance) intrigues me. Sea lions have been seen on local rivers, over a hundred miles from the ocean, and are posing major risks to steelhead numbers, which impacts recreation and ecology. I’m drawn to stories that seem to have easy answers—over fishing or oceanic pollution in this case—but upon review, have complicating factors, like, are the sea lions starving at sea, or are they exploiting ready food sources inland? I’d have to see a lot of the Northwest and North coasts to be able to draw any reasonable conclusions—and that would be a wonderful way to spend a year.

DD: If you could be reborn as a bird, which bird would you like to be?

CB: Probably a crow. They seem to watch out for one another and have a good time when they can.

DD: What is something you are obsessed with right now? It could be a hobby, a TV show, a dish, anything.

CB: I am deep into sweater knitting, having finally settled down somewhere that is at least chilly for much of the year. Since moving back to Oregon, I’ve finished nearly half a dozen, and I have a dark green wool pullover on the needles right now.