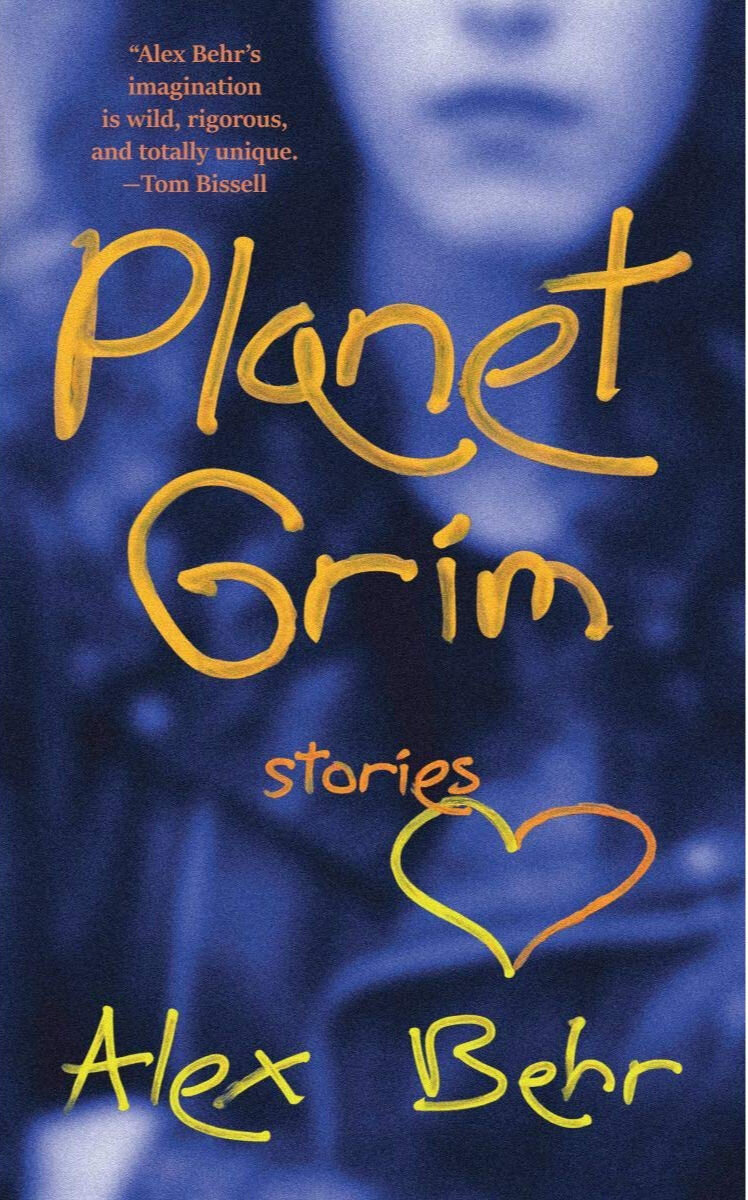

Alex Behr's Planet Grim

Planet Grim is difficult to describe because it’s such a complex (and often complicated) gathering of short stories. There’s pain and suffering, but humor is just as prevalent. Imagine a Flannery O’Connor world written by David Sedaris.

In “Teenage Riot,” one of the first—and best—stories in Alex Behr’s debut collection, Planet Grim, a broken teenage girl admits, “I want something to love.” It seems like such a simple statement, but, like the stories with which it shares its space, there’s much more happening beneath the surface.

Planet Grim is difficult to describe because it’s such a complex (and often complicated) gathering of short stories. There’s pain and suffering, but humor is just as prevalent. Imagine a Flannery O’Connor world written by David Sedaris. In “Wet,” for example, we find an unnamed woman struggling to deal with her recent divorce. Her pain is real: “I cut off my left arm with nail clippers. It hangs on. I can’t snip the final pieces of dried-out skin.” But Behr gives the story an added dimension by juxtaposing the immense sorrow with comedic absurdity. The woman says, “I have stained teeth and an undeniable love of cheese.”

“A Reasonable Person,” another one of Planet Grim’s standouts, strikes a similar balance. Here, Mary, a juror on a murder case in which a boy saw his mother murdered, can’t focus on the trial because she’s so overwhelmed by the struggles of her own life. Some are seemingly minor: she worries about when to urinate and if her armpits stink. Others, though, are much more serious. After going home, she removes her own absent son’s clothing from a drawer and cradles them on a bed. She talks to him intimately. It’s unsettling, but Behr works her magic again. Mary says to her son’s scattered clothing, “You ran pretty damn far from me!” It becomes heartbreaking.

“Sentient Times” and “The Garden” are two other stories that show Behr at her best, shifting tones and engaging in affecting wordplay. She’s a master of language, and these stories show a meticulous command.

One of the most appealing elements of Planet Grim is how Behr focuses on characters who are so realistic. These are characters who are identifiable misfits—maybe our own family members or even ourselves. They are struggling, but they are still fighting. There are issues with drugs, parenthood, childhood, divorce, and death. Even in their most desperate situations, they are still relatable.

At twenty-eight stories, Planet Grim could lose a few of the stories and, perhaps, be a little stronger. Having so many stories with dynamic shifts and quirks creates an occasionally fragmented overall experience. The ones that do work, though, and just for the record, most of them do work, sing.

Planet Grim is an affecting debut that should remind us how we’re all fighting a tough battle.

Sunlight on Grief: A Review of Mystery and Mortality by Paula Bomer

Grief is unwelcome and, like an unwelcome guest, has a way of sticking around long after the party’s over, chairs are stacked, and the light’s turned out. Working around grief’s hidden edges, that’s what we struggle with, like breathing through glass. Paula Bomer’s exceptional new book of essays, Mystery and Mortality: Essays on the Sad, Short Gift of Life, is breathing through those shards in any way it can.

Grief is unwelcome and, like an unwelcome guest, has a way of sticking around long after the party’s over, chairs are stacked, and the light’s turned out. Working around grief’s hidden edges, that’s what we struggle with, like breathing through glass. Paula Bomer’s exceptional new book of essays, Mystery and Mortality: Essays on the Sad, Short Gift of Life, is breathing through those shards in any way it can.

Much of Mystery and Mortality is personal: about Bomer’s mother, her children, her father, somatic pain. But interspersed are meta-musings on literature, on Tolstoy, Gaitskill, Flannery O’Connor (lots of O’Connor), DFW. At first, the sequencing bothered me. What in the world does Tolstoy have to do with dementia?

We work through grief in our own ways. Some eat our feelings to the tune of Haagen Daz, others exercise until exhaustion. Bomer chose to exorcise her demons by seeking an explication of suffering through works of literature—how pain and grief in fictional and non-fictional worlds runs in rivers beneath sight. By uncovering these truths, Bomer came to understand herself, “To what extent that suffering is or is not a result of our free will seems almost irrelevant…How to—to quote Wallace again—say to yourself, ‘this is water, this is water.’”

Bomer doesn’t conceal the grief in her life, she exposes it, hoping that sunlight will wither it. In the aptly titled introductory essay “My Mother’s Dementia,” Bomer writes, “It unnerves me, the possibility that we never stop wanting our mothers.” She is forced into a caregiver role but also craves her mother’s protection and benediction, succor from a once-strong, once-capable woman whom Bomer might not have liked, but admired. “She was insanely beautiful and righteously smart …. Later, I understood that those two things, when combined, are the things the world hates most in women.”

While Mystery and Mortality’s content is upsetting, there are moments of levity. Bomer’s blunt honesty transforms simple prose amusingly, curmudgeonly. “I looked out at all the beauty and thought, ‘All this beauty, too bad it is full of Austrians,’” she writes, feeling melancholy in the midst of bucolic nature. Bomer understands that without the relief of comedy, pain is unendurable. Even when discussing her mother’s failing mind, she’s funny: “When my mother first became demented, I thought she was just being really annoying.”

Besides the pain and humor, Bomer allows her exploration of sorrowful moments of beauty. In the essay “Under the Jaguar Son,” in which she deconstructs cannibalism, her love of her children, and Calvino, there are lovely, strange lines that play jump rope with prose poetry, “We eat pussy or cock, we eat each other…Perhaps also, we are always consuming and wasting as we go about our living, birthing, begetting, and dying.” The will to beautify tragedy is redemptive.

Perhaps my favorite essay focuses on the villain in Cormac McCarthy’s novel No Country for Old Men. Unlike McCarthy’s legions of male fans, who perhaps glorify the darkness in his prose, Bomer takes a counter point, seeing the implacable villain as an avenging angel, meting our dark vengeance as, “…an angel, sent by God to destroy all of those who suffer from greed.” This interpretation, while seemingly odd, makes a certain amount of sense when taken in the context of the whole collection. It’s relatable to the age-old question of why God allows evil and suffering. The answer reminds me of the film Jacob’s Ladder, “If you’re frightened of dying and holding on, you’ll see devils tearing your life away. But if you’ve made your peace, then the devils are really angels, freeing you from the earth.” I see comfort in that.

The redemptive powers we possess, and the enemies of our own nature are what Bomer’s book revolves around: “What strikes me most is the idea that smugness—not violence or vitriolic hate (although yes, that as well)—is the opposite of compassion.” While she feels grief as deeply as we all do—“After my father’s suicide, after I’d alienated my friends, I felt I lived in a bubble…Often I would crawl the walls, screaming out for my father…,”—the book is her redevelopment of connections sundered by loss. She heals through text, through communion with other writers, likeminded souls. For readers, there’s a lot to learn, “Because once you acknowledge you have a soul at stake, you have a lot to lose.”