The Way I Sleep Is Sporadically and Often Desperately

The Way We Sleep really covers everything, even the things that haven’t happened to me. It’s beautiful and grotesque and touching and tragic and funny and playful and philosophical and magical.

If you were to see my bed or even my bedroom, it might be hard to think someone sleeps there. Books, paper — so much paper just somehow everywhere — clothes, letters, those envelopes and boxes people mail books in, Gameboy Advance games — only Pokémon, really—a toothbrush, pens, used up batteries, and all kinds of random cords that belong or once belonged to something I needed. The way I sleep is sporadically and often desperately. Somehow, The Way We Sleep captures all of this and so much more.

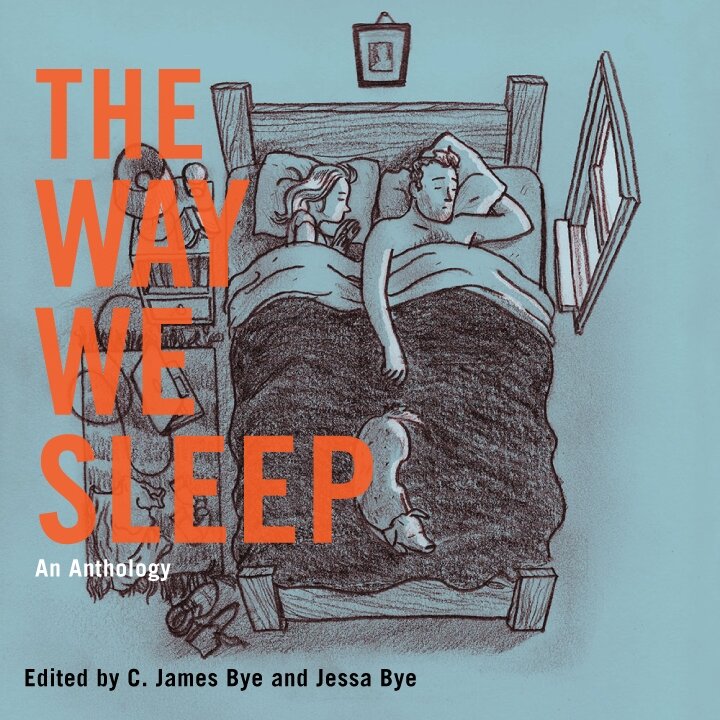

I don’t like anthologies and have maybe read one or two before picking up Jessa Bye and C. James Bye’s The Way We Sleep. Knowing I had a deadline to read this, I was not looking forward to it. Dreading it, really. Anthologies or even just normal short story collection can take me months upon months to get through and so I was expecting to have to send some disappointing emails this week, explaining I was still only on page 20. But then just three sittings later, it was all over and I was shocked by how quickly it went, how easy it was, how beautiful and painful those pages were.

I have had a very tumultuous relationship with sleep and my bed. Dreams, though, we’ve always been on the same team. But the bed, it can be a lonely place, often a haunted place, a crippling and emotional place. Now, if I were to try to explain what my bed means to me, I’d probably just hand someone The Way We Sleep. It really covers everything, even the things that haven’t happened to me. It’s beautiful and grotesque and touching and tragic and funny and playful and philosophical and magical.

The writing in here is mostly top notch, with my favorites being by Roxane Gay, J.A. Tyler, Etgar Keret, Matthew Salesses, Tim Jones-Yelvington, Margaret Patton Chapman, and Angi Becker Stevens, whose story was my absolute favorite and the one I still cannot stop thinking about. There are a few stories that fall short, but this book is really full of amazing things, and for every story that misses, there are five that hit in ways you never imagined.

And it’s not just full of short stories, but also quick and funny and weirdly insightful interviews and comics. The comics were one of my favorite parts of the reading experience. Right in the middle of the book, it works as a sort of breather from the prose. Playful and funny and emotional, the comics really rejuvenate you and make it so you need to keep reading. For me, even more than that affect is the fact that I dream weirdly often in cartoon. I mean, to see my dreams reflected in a book is one thing, but to see them drawn out is really something else. Something deeply satisfying and beautiful.

The Way We Sleep just works. Maybe it shouldn’t, but it does. Jessa Bye and C James Bye have done a tremendous job here, because editing a book like this is much more than simply checking grammar. The structure and juxtapositions of this book make for an extremely gratifying reading experience and allows the pacing to never get bogged down by similarity of content or tone or style. This is a collection of stories, comics, and interviews that just speeds by.

Being released just in time for the holidays, I can’t recommend it enough as it would be perfect for friends, lovers, and family. There’s something in here for everyone, whether they’re looking for sex or love or humor or just something to pass these cold wintry nights.

So, yes, The Way We Sleep is something you want to read. But be sure to keep it next to your bed, just in case.

Something About KA-BOOM: An Interview with JA Tyler and John Dermot Woods

No One Told Me I Was Going To Disappear combines writerly with painterly, harnessing the energy of a natural formal conflict and resolving it toward the common purpose of so much art—the love story. No One Told Me I Was Going To Disappear tells us a great deal. Not only do we find a story in which to lose ourselves, but a lesson in the nature of story-telling itself.

Stories, like the universe, are born of conflict. Electrons combine and collide, energy is born, KA-BOOM. Characters shout or sexualize, murder or meddle, KA-BOOM. As readers, we yearn for the KA-BOOMy climax. We lose ourselves in 800-page novels, needing to know what happens next. That’s narrative.

Sometimes a conflict is born off the page, between the reader and the words. The reader doesn’t quite comprehend what’s written, stops reading, thinks, and then, KA-BOOM. The reader emerges victorious over the un-understanding.

Like this, conflict makes us smarter, too.

So — here’s a Picasso quote with which I found myself conflicted:

“Often while reading a book one feels that the author would have preferred to paint rather than write; one can sense the pleasure he derives from describing a landscape or a person, as if he were painting what he is saying, because deep in his heart he would have preferred to use brushes and colors.”

I opened No One Told Me I Was Going To Disappear believing all art forms equally valid. But, like Picasso assumes above, still in conflict with each other. While painting beats writing for Picasso, most writers, I believe, will disagree. Because — KA-BOOM — writing is the most versatile of forms, a kind of code that worms into the hard-wired emotions. No matter how beautiful the painting or song, language can match (or exceed) it. (As a writer with no talent for drawing and deeply imperfect pitch, I have to believe this).

But in this extraordinary piece of art, JA Tyler and John Dermot Woods refuse the matter. No One Told Me I Was Going To Disappear combines writerly with painterly, harnessing the energy of a natural formal conflict and resolving it toward the common purpose of so much art—the love story. No One Told Me I Was Going To Disappear tells us a great deal. Not only do we find a story in which to lose ourselves, but a lesson in the nature of story-telling itself.

KA-BOOM.

*

Over the last few weeks, J.A. Tyler and John Dermot Woods were kind enough to elaborate.

JOSEPH RIIPPI: You likely won’t be surprised that what I want to begin asking about regarding No One Told Me I Was Going To Disappear is the relationship between the text and artwork. Can you talk a bit about that relationship with regards to the writing of the book? How much did the art inform the text, and vice versa? Were the artwork and prose created simultaneously or responding one to the other? What can you say with regards to your being “co-authors” as opposed to author and illustrator?

J.A. TYLER and JOHN DERMOT WOORDS: No One Told Me I Was Going to Disappear is a novel composed in art and text where each individual piece of art is a new chapter in the story, and each individual text is likewise a new chapter. But in terms of how the book as a whole was created, it was very much a dialogue between artists. Once we had struck a deal to do a project like this, which mostly consisted of a few emails saying “Want to do this?” and “Hell yeah,” John composed the first piece of art, the opening chapter, and sent it to J. A. Tyler. Tyler then wrote a piece of text as a response or conversation with that piece of art. When Tyler was done, he sent that text to John who would then compose a new chapter of art as a response to Tyler’s words. We did this, back and forth over the course of nearly a year, and the result was a co-written novel, a book that we believe is pretty unique in that it isn’t illustrations for a text and it isn’t a graphic novel, it is a collaborative narrative told in two mediums, by two authors, one chapter at a time.

JR: There seems to have been a conscious decision on your part to keep the artwork on equal terms with the text, too. The first and last chapters of the book, for instance, are pieces of artwork. Can you talk about that decision, to introduce your reader via artwork as opposed to language?

JATAJDW: It wasn’t exactly conscious to begin and end with art. John started the story and he decided to draw something. We also found an end in a chapter that happened to be drawn. We were interested in the narrative possibilities of words and images working together, but not in the more organic mode of comics in which they occupy the same space. Once we finished the book, we were pleased at how complementary the two storytelling approaches are. There is certainly no impression of ‘illustration’ or ‘captioning’ in this novel. It does seem that despite our increased ability to interact with non-textual work, images still largely work as inessential elements of literature (as ‘added bonuses’ or as a marketing element). We’re glad that No One Told I Was Going to Disappear functions as story told in words and told in pictures.

JR: Many independent presses are known for taking a great deal of care in the production of their books. Jaded Ibis goes even a step further with their fine art and sound editions. In the fine art editions for this, the reader has to make a decision between destroying the artwork to get to the words, or destroying the words to get to the artwork. Doesn’t this in some way contradict the “normal” edition of the book, where the text and artwork mingle? Are the fine art and “normal” editions meant to stand alone, or should they be considered equal parts of the larger artwork?

JATAJDW: Debra DiBlasi (our publisher) might be able to answer this question better than we can, at least in terms of her idea of doing these editions for all of our books. But, for us, we wanted an edition that basically indulged the obvious fault line that we had left in our work. Our collaborative method of composing a whole novel together, but sections independently, leaves the scars of our work showing. By not combining words and pictures in single sections, the separation, and hopefully tension, between these two methods of storytelling remains obvious. We wanted the fine art edition to irritate this threat that the words might overtake the pictures or the pictures might consume the words, and basically force our reader to do just that.

JR: The jacket copy describes the book as both “horror story and love story.” In my first read, it felt much the latter, perhaps because that’s the kind of story I was looking for at the moment. But in a second read, I found myself more drawn to what I guess one would call the “horror” aspects, the moments of separation. (Maybe it’s the same reason). The tension between the images and text, and the tension within the images and text themselves, seems to draw from this simultaneous coming-together and ripping-apart, emotionally. I’m curious if you find or found yourselves falling one way or another in your own emotions for the book. Does your own unified voice (as in these answers) come from equal-and-opposite forces, or parallels?

JATAJDW: Wow, Joe. I think the answer is “yes.” You described our exact experience. As we passed the story back and forth, the constant challenge was to invent (change) but by harnessing what had been given to us. The fact that this novel ended up being a story about the absolutely terrifying nature of love — the fear of loss, both of self and the person or thing that you can’t control — seems to be a likely result of the way we worked together.