A Review of Four Quartets: Poetry in the Pandemic

Three deep bows to the editors of this rainbow, this cornucopia, this star-studded cast of gifted poetry makers. . . . On page after page, they invite the reader to view this pandemic through a renewing prism. COVID-19 will be fuel for all kinds of art in the future; kudos to these poets for writing insightfully about something so immediate.

Three deep bows to the editors of this rainbow, this cornucopia, this star-studded cast of gifted poetry makers. They did not trick out the poetry with fancy fonts or graphics; the words speak for themselves and that feels right.

At least one poet had the virus, some are old, some young, some write in pairs, one has been translated from Korean. One displays show-don’t-tell photographs. On page after page, they invite the reader to view this pandemic through a renewing prism. COVID-19 will be fuel for all kinds of art in the future; kudos to these poets for writing insightfully about something so immediate.

Each poet deserves to be experienced as to style, format, historicity, influences, philosophy, and more, but a book review must, regretfully, skip through this rich trove with but a few brush strokes for each. Perused at your leisure. There is so much to think about, so much to savor. If you think you know this pandemic, think again.

Jimmy Santiago Baca’s first people’s heritage thumps through his poems. The archetypal buffalo brings us back to the real, the power, the spiritual bedrock.

Gentle heart you are,

I would say

Sumo-sweetness, the prairie breeze

So bracing it recalls your soul

To times you ambled in amber citrus fields…

Sumo-sweetness, what a way to describe the heavy, powerful, surprisingly lithe buffalo!

Yusef Komunyakaa and Laren McClung, teamed up. Their lush language encompasses all living matter, from the moment when creatures emerged from the swamp to today, from here to Papua, New Guinea. One poem stops to witness “the way a coyote or band of raccoons/might wander out of Central Park/up Fifth Avenue & climb the MET steps.” Here. Now. The pandemic world is just one of their many, but “Don’t worry, love, there’s nothing in the world of mirrors that is not you looking back…”

Stephanie Strickland’s poems are notional.

Belief

in

The existence of other human

beings as such

is

love

The punky, punchy groove climbs into the reader’s head and bounces around until it lands someplace, and you say, “Yeaahhhhhh.”

Mary Jo Bang’s poems creep in at a petty pace: today, today, today. “Today I thought time has totally stopped. There is no/foreseeable future and the present so overwhelms the past/that it hardly exists.” She presents Purgatory, neither here nor there, a dreadful aloneness. Her head is “Kafka’s crawl space in/which something alive is always burrowing.” “The world is too much,” she writes, “too much with me.”

Shane McCray’s poems feel like they fell off the back of a truck. He tosses off his observations in delightful, unexpected, well researched detail. While skateboarding, he is in a “city where there isn’t/A city anymore.” He inhabits his physical self “as if my body were haunting my body.” Things are not as they were, as they seem, or even as he can properly understand them, which gives him a chance to become something new. His poems reveal great intelligence but little salvation, perhaps some guideposts to understanding.

Ken Chen is discursive, fluent, erudite, political. He sees out today’s Apocalypse unfolding “under the sallow iPhone lamp…Shout over the police who have prohibited even breathing…the planet spools out its fraying thread of days…where they threw hoses at prisoners and led them into the burning forest…” Chen’s recitation of horrors flows on, from the obscene photos of the dead boy on the beach in Bodrun to some cute deaths involving Harry Potter and Minnie Mouse. He exhorts the reader to remember them: “I inspected each name and mounted them in the bezels of the text.” There is a surprise ending. Chen snaps his fingers, “what we remember/replaces what remains, the lost are soon forgotten, and We hold hands, we run,/we leap into the waters.” May it be so.

J. Mae Barizo offers the prayer that “…the light/will lick and lick the damage clean. That it is not/ruin already.” She ushers the reader through first poems filled with flowers and light, into a place where the prognosis is poorer. Her metaphors are delightful: “outside the pedestrians gleamed like pinpricks, or listening to lovers/sleep, breathing/like monster trucks.” Her spirit cannot resist hope despite evidence to the contrary, and the reader is taken on a soft-loving ride through the ruins.

Dora Malech tours the headlines of this dire time, writing as if in a diary. She reminds us of the little girl who drowned on her father’s back as he tried to cross the river to America, of the penguins starving in the winter, torahs. She writes “I had waded into the Information and come back dragging a/haul of names. Still soaked, they marked a trail in the sand/behind me as I pulled them from the River.” Malech is trying to keep up her hope while suffering in the strange, unexpected ways that we are all suffering.

Smack dab in the middle of the book comes B. A. Van Sise with his photographs. A welcome visual break. They are evocative, not pretty. Why is that man the only one not wearing a mask? Why is that other man clutching his child with such sad determination? Hail to that essential worker, serving in the boring convenience store to save us. Thank you, editors Kristina Marie Darling and Jeffrey Levine, for including these photos among the poetry.

Jon Davis is an old man with nothing to lose. Might as well tell the truth as he sees it. He confronts the pandemic and learns what he already knows, only more so. Life is an uncertain enterprise. He mentions the “layers of history”, recalling the work of another elderly poet, Stanley Kunitz and his poem The Layers. Such is impermanence—layers of good on bad, rich on poor, happy upon unhappy. He rewards us with humor: “we remembered the ‘kids’ were thirty-something…speaking a language we didn’t recognize at all.” And how about this, “the skunks ambled through the arugula like mental patients.” Favorite metaphor: “…music seeping into the lobby like radiation.”

Lee Young-Ju’s work is translated by Jae Kim, and bravo to him. It couldn’t have been easy. If Salvador Dali had written poetry, it might be like this, full of trompes d’oeils, flippant about the rules, running through a place that is familiar but not like anything you’re ever seen.

Lee is Korean, and her poems have sieved through a different history, a different culture. As in much Asian art, there is no attempt to keep time and space in perspective. The poetry is made of images, smells, wind on the skin. “Languages are afloat, like feathers,” or “What’s this breeze that has leaked out of my soul?,” or “Girls gather in the alley and talk without moving their lips.” The reader can see, hear, and feel it, and the rhythm and pungency carry her along, as if she were in the blind tunnel at the amusement park. Though some images are of wreckage and despair, they’re still yummy. “I remain in the whirlwind and continue to be thrown away.”

Rachel Eliza Griffiths is another prose poet. Reading her work is like going to the spa; every touch, smell, warmth, and chill is palpable, meaningful, and healing. She addresses the pandemic in its atomic expression, taking us through the near death feelings when engulfed by a 103-degree fever. She shows us the virus from inside the body of a person suffering from it. She wonders, “Will I come through this if my body does not come with me?” She honors Tamisha, the forensic technician who places daffodils on body bags in the hospital morgue. In a bow to another aspect of our times, she remembers the Black lives lost. She steps back from the atomic in the end to comment, “The virus rears in sunlight, devouring bodies that will not mask, separate, isolate, listen. The virus is the arrow of the nation’s ego.”

A.Van Jordan’s poetry skims along accessible, meaningful. He encounters quarantined, sheltering people and “I ask them/and—is it possible, for the first time?—/I truly wanna know” echoing Meghan, Duchess of Sussex’s recent op ed that pleads with us to ask each other in this perilous time, “How are you?” Jordan picks and chooses his vocabulary and his allusions. He “hangs out,” talks of “swagger,” then he turns to Prospero, Caliban, Queen Elizabeth I, Shakespeare. His comparison of the words of Queen Elizabeth I and Donald Trump is a walloping riposte to those who dismiss racism and repression. Yes, this has been going on a for a long time. He quotes Langston Hughes, “I dream a world.” The juxtaposition of the high-fallutin’ with the everyday jolts the reader into acceptance of universality. Can’t keep this man down. “[.]..we continue long into night/into the coming day, a Soul Train of revolt/lining rural routes, and filling streets/in our cities with dance.”

Maggie Queeney writes “Inside the Patient is another Patient, perfect, and one/size smaller. Inside that Patient is another, and another,/perfect.” A poetic symphony of compassion for the suffering, the lost hopes, the destruction of what should have been. The patient is delivered “Into the hands of others, their palms slick with/alcohol or cloaked in latex in a blue chosen/for its quantified calming effect…” Queeney is writing what she knows, catching fragments of reality, of truth, and laying them on a silver platter for us.

She kneads the subject of “Patient” into many shapes, each enlightening, the words lovely and clear. “The Patient’s Book of Saints,” “The Patient has a History of Medical Treatment,” “The Narrative Arc of the Patient,” and so on. Not only does the situation of the Patient change, but the structure of her poems changes as she paints each with a different brush. If Queeney hasn’t been trained as a nurse, she sure feels like one, detail-oriented, caring, effective, sure.

Traci Brimhall & Brynn Saito are co-authors who sink into the senses, colors, and impressions of life, but yearn for certainty, for the power to protest. Theirs is a record of the isolation of the pandemic, but they also bring along the rising waters of climate change and the rife injustices that remain unaddressed. Ruin awaits. So what do you do?

Dusk summons me home with its sapphire curfew.

Do you want to know how I do it? I expect nothing.

And then, and then, the bright surprise of your arrival.

A poet cannot give up hope; it is her substance, her living. Who would bother to distill the essence of things if not to inspire others to rise above themselves and save us?

Denise Duhamel jumps right in: “I saw the best minds of my generation (i.e., Fauci, Birx)/Undermined by Trump….” This poem is titled “Howl,” a reference, perhaps an homage, to Allen Ginsberg. Just when you thought you’d heard the first draft of history told in every possible way, she comes up with a new way. She condenses the tiresome facts into an energy pill, then repeats: canceled doctors’ visits, essential workers, no visits to mom, masks. Duhamel pummels the reader again and again. “2020/always sounded to me like a sci fi year/but now it is here with a pandemic predicted/by both scientists and sci fi.” That doesn’t sound like poetry, but in Duhamel’s hands, it is. Here is our Samuel Pepys. Here’s the bam bam bam, and then bam, bam, bam, of indignity, sacrifice, loneliness, helplessness, the revitalization of Nature as everybody stays home, the lies, the needless death, the brutality—read on.

Rich Barot is the perfect final act, a series of effortless (lol, as if), funny, insightful, touching poem-paragraphs full of images, turns of phrase, palpable reality. Here is the last of them:

During the pandemic, I listened. Things hummed their tunes.

The pear. The black sneaker. The old-fashioned thermometer.

The stapler with the face of a general from Eastern Europe.

Once, my father confessed he had taken the padlock from his

Factory locker and clipped it on the rail of a footbridge at the

Park. He had retired. The park was near his house. Each time

He went there, I imagined him feeling pleased, going to work.

*

This review is but a tiny taste of a novel and enchanting work. Keep it at your bedside for a laugh, a tear, a thought, an inspiration.

A Conversation with Bonnie Jo Campbell and Andrea Scarpino

One might make the argument that two of the strongest voices in contemporary Michigan are Andrea Scarpino, representing the Upper Peninsula poetry scene, and Bonnie Jo Campbell, representing the Lower Peninsula fiction scene. The strength of their voices comes from a combination of having unique, distinctive, and passionate style and subject matter on the page, furthered by both authors willingness to tour extensively, notably to rural communities in the state.

One might make the argument that two of the strongest voices in contemporary Michigan are Andrea Scarpino, representing the Upper Peninsula poetry scene, and Bonnie Jo Campbell, representing the Lower Peninsula fiction scene. The strength of their voices comes from a combination of having unique, distinctive, and passionate style and subject matter on the page, furthered by both authors willingness to tour extensively, notably to rural communities in the state. Scarpino is the 2015-2017 U.P. Poet Laureate whose latest book is What the Willow Said as It Fell (Red Hen Press). Bonnie Jo Campbell is a previous National Book Award finalist whose current book is Mothers, Tell Your Daughters: Stories (W.W. Norton & Company).

*

RR: Both of you are brilliant with titles. I’m a big fan of the cryptic Once, Then and the best title of 2015 might be Mothers, Tell Your Daughters: Stories with its lovely double-entendre of “Mothers, tell your daughters stories.” Can you talk about your book titles?

AS: Thank you, Ron! Your compliment means a lot to me because I really struggle with titles. When I was doing my MFA, one of the recurring criticisms of my workshop submissions was that I needed a different title, and I often go through dozens before I find one I really like. They just seem so final—like naming a child.

I really like titles that simultaneously shape the reader’s expectations and withhold a little bit of information from the reader. I want the reader to be interested in opening my book, but I also don’t want to be too explicit about the book’s content. In both my poetry collections, the titles developed from lines within the book itself which I hope readers will recognize when they’re reading. In my second book, the line, “what the willow said as it fell” is followed by, “Take this body, make it whole.” So I liked What the Willow Said as It Fell as a title in part because I’m hoping the idea of wholeness, and obviously the fact of the body, shines through the poetry.

BJC: Thank you, indeed, Ron! I’m with Andrea that titles are hard. And I might even go so far as to say that a work is not finished until it has the right title on it, and for me the title is often the last element of the story or collection to come to me. That said, after I get the right title, by settling into the final understanding of my work, then I have still more work to do, adjusting the whole work slightly to the title. The titles to all three of my collections have great stories behind them, and I’ll say that I spent months coming up with Mothers, Tell Your Daughters. I had this story collection, but didn’t quite know what it was about. After trying out hundreds of other titles, arguing with my editor and agent, and stressing endlessly, I finally came upon this one. It resonates especially for me because it’s a line from the song “House of the Rising Sun” when sung by certain female artists. Once alighting on that title, my editor and I made some adjustments to the collection, leaving out a few stories that no longer fit and requiring me to write two new stories, including the title story. American Salvage has a similar story behind it, in that the title story was the last one I wrote. My novel, Once Upon a River, has a different story behind it. My agent came up with that title in the shower. We sold the book with that title, and I didn’t like it for a long while. Finally, when I saw the title allowed me to be fantastical, I embraced it, and I still like it.

RR: You both write about suffering frequently. What role does suffering play in your fiction and poetry? Do you handle it as redemptive or existential?

AS: I don’t think there is anything redemptive in suffering. It’s just suffering: it just hurts. I actually respond very negatively to suggestions that suffering makes us better people or enriches our lives in some deep way. I know some people derive meaning from their suffering and I’m glad for them when that’s the case, but the only meaning I’ve been able to derive from painful moments in my life is this sucks. I want this to end.

Suffering is an integral part of being alive and being human, which is why I so often write about it—I don’t think a single human being is spared suffering. And yet, we so often like to pretend we don’t suffer. We’re told to put on a brave face, and women especially are told we should smile no matter what is happening in our personal lives. So I think it’s incredibly important to acknowledge and sit with suffering, to understand it as a central human experience, and to appreciate the suffering of others around us. And writing and reading about suffering can help us with that.

BJC: I tend to write about what worries me, and the suffering of others worries me immensely. We fiction writers tend to write about suffering that comes about both because of circumstances and also because of the nature of one’s character—it is most interesting when a character has at least partially brought about his or her own suffering. I don’t write as a sociologist, and my main interest is in exploring the human character, but I am glad when my readers tell me that they have more sympathy for the sorts of folks they encounter in life because of my stories. Like Andrea, I see suffering as universal. Nobody’s life is easy when you come down to it—we want to pretend some people swim effortlessly through life’s waters, but life is hard for everybody a good portion of the time. And while I don’t see suffering as inherently redemptive, I do think it can sometimes spur a character into action.

RR: What religion do you identify with? What’s your religious/spiritual background?

AS: I don’t identify with any religion in all honesty. My father was Catholic so I have spent a fair amount of time in the Catholic Church, and my mother identified as Quaker for a while, so I spent time at Friends Meetings. I also grew up with dear friends who were Jewish and Muslim, and as an adult, I’ve read some about Buddhism. So I guess I have a bit of a smorgasbord religious background, which also means I don’t have a deep understanding of any one tradition.

BJC: Andrea, you and I need to have a beer! How have we never sat down together?

RR: The following is quoted from Mothers, Tell Your Daughters:

“I’m not going to hell,” he whispered. “God is leading me home. He has shone his light on the path to Him. God has forgiven me.”

“For what, Carl? What has God forgiven you for?”

“Forsaking Jesus.” He sounded exhausted, his voice a hiss.

“What else?”

There was a long pause before he whispered, “Jesus is my Lord and Savior, my light in the darkness.”

“How about forgiveness for hitting your wife? And your son? Is God forgiving you for that?”

Could you talk about this passage?

BJC: The passage is from the story, “A Multitude of Sins,” a man who has abused his wife and son finds Jesus right at the end and so figures he’s saved. When the husband is dying of cancer, the wife begins to discover the seeds of her empowerment. She finds herself furious at the notion of her husband receiving forgiveness. I enjoy seeing this woman become angry after a life of submissiveness.

RR: Andrea, in your poem “Homily,” you repeat the phrase, “She didn’t believe in God.” Why that repetition?

AS: My poem “Homily” was based on an experience I had while visiting Paris and walking into Notre Dame on Christmas Day: the priest was saying the mass in Latin, and the air was filled with incense and evergreen, and I was completely in love with being there and being present in the moment even though I don’t identify as Catholic. So I guess I tried to capture the feeling of wanting so badly to believe in something because the present moment is so special, but also knowing, deep down, that belief is just not there.

RR: Do you find you struggle with your religious beliefs through your characters?

AS: I don’t know if I struggle with my own religious belief through my poetry, but I definitely am a person who questions almost everything, including religious belief, in my life and in my poetry. I like feeling open to the world, and I like questioning, and I like hearing about other people’s beliefs, and I like learning how other people experience the world around them. And I find religious belief endlessly curious and interesting and rich with possibility.

BJC: I’m not interested in my own religiosity, but I am interested in the religious beliefs of others, and as a writer, I’m interested in seeing how those beliefs inform character.

RR: Bonnie Jo, Halloween appears in Once Upon a River and Q Road, notably in the passage on “Halloween [where], he’d soaped windows, strung toilet paper across people’s front yards, and once he’d found a veined, milky afterbirth from his sister’s horse foaling, and in the middle of the night dragged it onto a neighbor’s front porch.”

Are you attracted to what an old Religion professor of mine, Dr. Hough, called the Jungian shadow aspects of humanity?

BJC: Katherine Dunn’s novel Geek Love has an epigraph from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, a line Prospero says of the monster Caliban: “This thing of darkness I Acknowledge mine.” I, too, acknowledge mine!

RR: Earlier, we spoke of suffering. Both of you are connected to metaphorical center points in Michigan—Marquette and Grand Rapids. Grand Rapids/Kalamazoo is emerging as an economic and spiritual powerhouse of the state, as well as important for Michigan publishing with Zondervan and New Issues Press. There is also the complication of poverty in the far southwest regions that grinds up against Grand Rapids’ wealth. Hate groups are in that area and the recent Uber driver murders. Bonnie Jo, where you live is a very complicated place. Can you talk about good and evil in your writing, how it fits with the complexities of southwest Michigan?

BJC: I was just reading Plainsong by Kent Haruf, and I was noticing how he makes very clear who is good and who is evil in his stories. I am more interested in gray areas of human nature, in people who try to be good, but fail, and in people who make trouble sometimes. The person who has a decent job and a good family situation might go his or her whole life as a productive law-abiding citizen, while the same person, after losing a job and a spouse and children might become a meth-addicted criminal. What amazed me about the Uber shooter is just how ordinary and normal he was; that showed me that crimes are not committed by devils or evil people necessarily. Crimes are committed by people who make bad choices, and they make them for a variety of reasons, some of which we will never understand.

All we can do, it seems to me, is pay attention, keep our minds open to all the possibilities good and bad, and work to care for one another at all times. We can strive to never be cruel or judgmental.

RR: Who are the great spiritual writers in fiction and poetry?

AS: I love Marilynn Robinson’s writing, particularly Gilead. I first listened to that book as an audiobook on a road trip many years ago, and I remember just weeping while I was driving because I was so moved by the quiet spirituality throughout her writing. And that quietness is really the kind of spiritual or religious writing that I most appreciate: a quiet attention to those around us, a quiet attention to the world, a quiet attention to the connections that make us human.

RR: What issues of religion do writers need to talk about now?

AS: Acceptance and appreciation of different opinions, viewpoints, and religious traditions. Our country’s hate speech deeply troubles me, particularly as it is directed toward Muslims. But we’ve never been particularly good at accepting differing viewpoints and that’s something that writers and religious leaders and teachers and parents and politicians all need to address.

BJC: As a writer I spend a lot of time imagining how it feels to be in someone else’s shoes, and that helps me be more humble and generous toward my fellow human beings, even the difficult ones.

*

Interviewer Ron Riekki’s latest book is the 2016 Independent Publisher Book Award-winning Here: Women Writing on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula (Michigan State University Press), which includes writing from Bonnie Jo Campbell and Andrea Scarpino.

Why Are We Whispering?

The voices in this book are diverse. As one of the workshop leaders writes in the book’s introduction, the words inside appear as they are “originally written, candid and unedited,” allowing readers “direct access to real and immediate worlds.”

She is wearing all white, dirty white, her ID number written in Sharpie across her chest. “I was a very ripe peach,” she says, facing the class. “I was about to be torn open so the pit inside could spawn more peach trees.” We’re in Alabama’s only maximum security women’s prison. “That’s what it felt like when you were being born,” she says. “My girl.”

She, let’s call her Della, holds her classmates in an unwavering gaze as she tells her story. After a year teaching in maximum security men’s prisons, this is my first experience with incarcerated women. Her eyes are steady on me too, the new instructor.

“Nurse, nurse, my water broke!” she calls out, rehearsing the monologue she’s crafting for her daughter. Just a few months before, she lived at home with her four children and husband. She usually made oatmeal for breakfast. Now she’s in prison for life without parole.

When Della finishes, another student stands, faces us. Mary tells us that she can’t read or write. Her voice is soft and low, eyes to the ground. She tells us that she’d like to get married in Disneyland. That she has brain damage from being beaten so many times as a child. Then, she lifts her chin and begins strutting across the room. “One day my prince charming will walk out of the ocean,” she says, swinging her hips, extending her arm toward the cinder block wall and fixing her eyes to where her fingers point. “And oh goodness, he is fine.”

Stopping at the gas station outside town after class, I lean against the peeling bathrooms and pinch my thigh to redirect the pain burning hot in my throat, in my heart. After the two hour drive home week after week, I sit alone at home or go out to the bars and occasionally try to tell one of my friends a story — there’s this student, I start to say — but it never comes out right.

All this — these stories, their incredible importance and the impossibility I’ve encountered thus far in trying to communicate them — is running through my head when I open the new book Hear Me, See Me: Incarcerated Women Write, an anthology of short prose and poems from the only women’s prison in Vermont. Here’s a piece of the first poem I flip to, “Merely Me,” by Raven:

Why am I ‘mentally ill’?

Why are we whispering?

How come they decided ‘I am mentally ill’?

I stand up and say my name and they look my way.

I say, ‘I am not perfect, is all.’

I raise my voice and say, ‘I am a person whose feelings are topsy-turvy, is all.’

Yes, I think right away. This. Why are we whispering? I am a person whose feelings are topsy-turvy, is all.

The voices in this book are diverse. As one of the workshop leaders writes in the book’s introduction, the words inside appear as they are “originally written, candid and unedited,” allowing readers “direct access to real and immediate worlds.” In the growing body of prison literature, some anthologies showcase the polished work of a few writers, but this book presents a whole spectrum of writing:

from the nearly illiterate woman struggling to pen a couple of sentences, to the college graduate who crafts a finished piece effortlessly; from the dyslexic woman stumbling to read back what she just wrote to the wheelchair-bound grandmother who utilizes writing as a form of prayer.

This is the kind of book we need, a chorus of largely unheard voices all shouting and whispering with joy and fury, all speaking about what it is to be a human, a woman human, a woman human who is locked away in America. The writing is about the time inside and also the depth and breadth of the lives outside.

“I know what I would be doing if I was home with my family,” TH writes in “If I Was Home.”

We would all be cuddled up on my bed with a big bowl of popcorn watching Halloween movies together.

Whether I flip between pieces or read sections chronologically, I am struck by the commonalities of the subjects, our most human — love, parenthood, failure, silence, loss, pleasure, anger, desire, abuse, ego, addiction, friendship. It is through the volume of voices collected in this anthology, page after page of women writing their truths, that this book gains its most potent force.

These are not easy stories. Many disclose hardships most of us will never face.

“I’m at war with myself,” Stacy writes in “Darkness and Truth.”

Me against the world. Alone. Angry. Bitter. Harder than I should be ’cuz I’m forced to be. And maybe it wasn’t just my choices. ’Cuz I still hear their voices.

Though literature is powerful, there are kinds of suffering that nobody else will ever truly be able to understand. But it is the collection of these stories, both terrible and elegant, that starts to transcend the limitations of individual experience and open the possibility for compassionate connection. These are voices we rarely hear from, not just because they are incarcerated, but because of the racial, social, economic and educational background of most people who spend time in prison. For that very reason, they are fundamentally important. But it isn’t just who we’re hearing from on these pages, it’s what, and how, and why. Beyond all the reasons these voices are singular, they also, in some way, echo all of our stories. And they do so beautifully.

“Give me the strength, the power/ to rise from the bondage of my addiction,” Tess writes in “I am Here.” “It is me, your daughter/ I am here, in your light,” she calls out across the blank page. And we are here too, we readers. We hear you, women writers of the Chittenden Regional Correctional Facility, and through your words, we see you.

Della’s daughter will not likely get to hear her mother tell her the story of her birth, her peach-seed-self blossoming into the world. I hope Mary gets to tell her Prince Charming about her plans for Disneyland one day. I’m not sure whether she will have the opportunity. These are complicated, emotionally irreconcilable losses present on many different sides. Nothing changes that. But I am grateful, very grateful, that a book like Hear Me, See Me exists, on whose pages we have the great privilege of reading the words all these daughters have chosen to share with us.

*

Sarah W. Bartlett (Ed.) directs Women Writing for (a) Change – Vermont, a community that midwifes the words of women for personal and social growth and change. She also co-directs writing inside VT, a program that supports writing-based reflection and growth among Vermont’s incarcerated women. It is based on the practices of WWf(a)C-VT.

The Way I Sleep Is Sporadically and Often Desperately

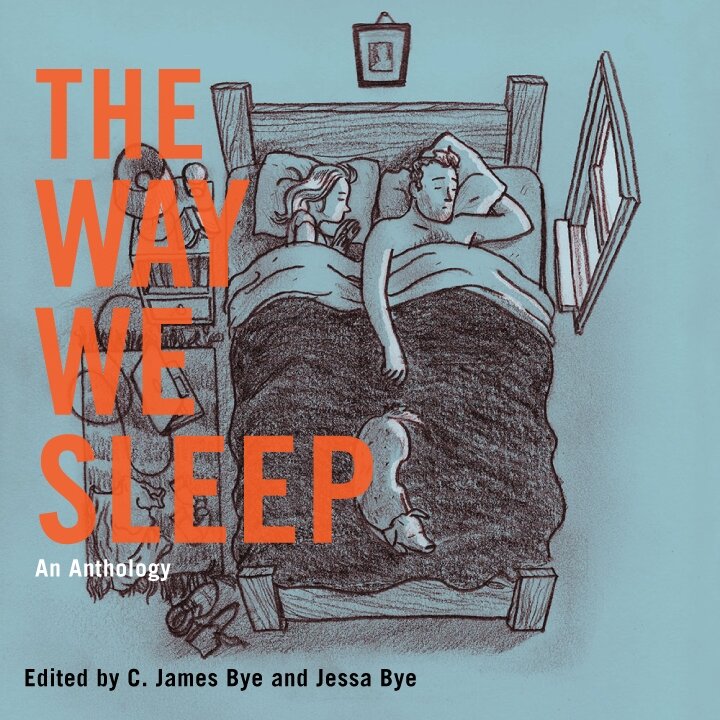

The Way We Sleep really covers everything, even the things that haven’t happened to me. It’s beautiful and grotesque and touching and tragic and funny and playful and philosophical and magical.

If you were to see my bed or even my bedroom, it might be hard to think someone sleeps there. Books, paper — so much paper just somehow everywhere — clothes, letters, those envelopes and boxes people mail books in, Gameboy Advance games — only Pokémon, really—a toothbrush, pens, used up batteries, and all kinds of random cords that belong or once belonged to something I needed. The way I sleep is sporadically and often desperately. Somehow, The Way We Sleep captures all of this and so much more.

I don’t like anthologies and have maybe read one or two before picking up Jessa Bye and C. James Bye’s The Way We Sleep. Knowing I had a deadline to read this, I was not looking forward to it. Dreading it, really. Anthologies or even just normal short story collection can take me months upon months to get through and so I was expecting to have to send some disappointing emails this week, explaining I was still only on page 20. But then just three sittings later, it was all over and I was shocked by how quickly it went, how easy it was, how beautiful and painful those pages were.

I have had a very tumultuous relationship with sleep and my bed. Dreams, though, we’ve always been on the same team. But the bed, it can be a lonely place, often a haunted place, a crippling and emotional place. Now, if I were to try to explain what my bed means to me, I’d probably just hand someone The Way We Sleep. It really covers everything, even the things that haven’t happened to me. It’s beautiful and grotesque and touching and tragic and funny and playful and philosophical and magical.

The writing in here is mostly top notch, with my favorites being by Roxane Gay, J.A. Tyler, Etgar Keret, Matthew Salesses, Tim Jones-Yelvington, Margaret Patton Chapman, and Angi Becker Stevens, whose story was my absolute favorite and the one I still cannot stop thinking about. There are a few stories that fall short, but this book is really full of amazing things, and for every story that misses, there are five that hit in ways you never imagined.

And it’s not just full of short stories, but also quick and funny and weirdly insightful interviews and comics. The comics were one of my favorite parts of the reading experience. Right in the middle of the book, it works as a sort of breather from the prose. Playful and funny and emotional, the comics really rejuvenate you and make it so you need to keep reading. For me, even more than that affect is the fact that I dream weirdly often in cartoon. I mean, to see my dreams reflected in a book is one thing, but to see them drawn out is really something else. Something deeply satisfying and beautiful.

The Way We Sleep just works. Maybe it shouldn’t, but it does. Jessa Bye and C James Bye have done a tremendous job here, because editing a book like this is much more than simply checking grammar. The structure and juxtapositions of this book make for an extremely gratifying reading experience and allows the pacing to never get bogged down by similarity of content or tone or style. This is a collection of stories, comics, and interviews that just speeds by.

Being released just in time for the holidays, I can’t recommend it enough as it would be perfect for friends, lovers, and family. There’s something in here for everyone, whether they’re looking for sex or love or humor or just something to pass these cold wintry nights.

So, yes, The Way We Sleep is something you want to read. But be sure to keep it next to your bed, just in case.

Fact or Fiction? Your Guess Is As Good As Mine: Herta B. Feely's Confessions

Confessions is an anthology comprised of twenty-two short stories and memoirs whose genres remain unrevealed unless you look them up in the “answer key” at the book’s end. This format provokes questions regarding the boundaries between “fact and fiction,” the degree to which the traditional definition of “truth” is acceptable, and the consequent liberties that authors take as a response to their own interpretations. Feely seeks to engage readers in the subject — to invite them to examine if they wanted a story to be true or not, and if they felt betrayed when it wasn’t what they expected.

I’ll admit it. I really respect James Frey. I followed the controversy surrounding A Million Little Pieces (which contained numerous exaggerations and lies) and its aftermath. I watched the Oprah interviews — when she grilled him, and when she made peace with him. I watched it all, and if there’s one thing that really stuck with me, it’s a comment that Frey made in his final meeting with Oprah. He said, “Let’s say you look at a cubist self-portrait by Picasso. . . . It doesn’t actually look anything like Picasso, or if it does, it does in ways that might only make sense to him.” This seems to suggest that there are more leniencies (and perhaps undeservedly so) in the categorization of genres in visual arts than in literature.

Before the start of his work of fiction, Bright Shiny Morning, Frey stuck in a humorous disclaimer that stands as an acknowledgement of his past: “Nothing in this book should be considered accurate or reliable.” If Herta B. Feely were to do the same, it would probably read something like: “Some of the stories in Confessions should be considered true, but it’s up to you decide which ones.”

Confessions is an anthology comprised of twenty-two short stories and memoirs whose genres remain unrevealed unless you look them up in the “answer key” at the book’s end. This format provokes questions regarding the boundaries between “fact and fiction,” the degree to which the traditional definition of “truth” is acceptable, and the consequent liberties that authors take as a response to their own interpretations. Feely seeks to engage readers in the subject — to invite them to examine if they wanted a story to be true or not, and if they felt betrayed when it wasn’t what they expected.

Knowing the way the book was set up, I read Confessions much more skeptically than I’d even read a newspaper. I was a juror and each story was a case. It frequently seemed that certain feelings were described specifically enough that one would have to have experienced them to write them so well. But still, “reasonable doubt” existed. I would often end up contemplating whether these segments seemed to be described a bit too specifically — whether more detail was revealed than one would have naturally noticed if the said events did, in fact, occur. On the whole, verdicts were difficult to reach.

At the heart of Confessions lies the big question: Does genre even matter, and do authors have a responsibility to inform their readers of the truth (or lack thereof)? George Nicholas, author of the anthology’s “If, Then, But,” states, “Pulp magazines of the ‘40s and ‘50s enticed readers with ‘True Confessions’ in 48-point type on their covers (would their reader have turned away from ‘False Confessions’?).” Nicholas goes on to say, “The Sonoran desert is part of the United States. It is also part of Mexico. But whichever side of the border you’re on, it’s still the desert. That’s what I think about fact or fiction. Makes no difference. It’s the story that counts, and the line has been blurry from day one.”

Confessions is an enthralling literary guessing game. Reading it, I often found myself disillusioned, stranded in the middle of the desert, wondering where the borderlines were and if it even mattered.

At the Top of My Voice in the Middle of the Main Square

A Megaphone has arrived. I spent the whole afternoon yesterday reading it, enjoying most of all the fact that this book of essays on the position of female poets in the society includes several essays by Croatian authors. I also remembered how you and I had started working together. At the time, I had been trying to persuade several Croatian poets to write on this topic, I wanted to publish their texts in the journal Tema and then send them on to you, for your research.

Dear Ana,

I’m happy to let you know that A Megaphone has arrived. I spent the whole afternoon yesterday reading it, enjoying most of all the fact that this book of essays on the position of female poets in the society includes several essays by Croatian authors. I also remembered how you and I had started working together. At the time, I had been trying to persuade several Croatian poets to write on this topic, I wanted to publish their texts in the journal Tema and then send them on to you, for your research. I recalled how difficult it had been to persuade the poets, but still, I had managed to collect about twenty essays and publish them in the special issue of Tema: “Women Poets.” Later on I had sent them to you and gradually forgotten all about that. After a while you had told me that a book was in the making, texts being selected and translated. The editors Juliana Spahr and Stephanie Young had chosen the essays by Croatian authors who, with the exception of Vesna Biga, had never been included in literary anthologies. They had picked those they had considered the most interesting. Later on, it turned out not to be easy to explain the choice. A lot of questions had been raised: Why those particular authors? Who were they to decide? Etc.

But, all of that doesn’t matter now. A Megaphone is in my hand. I impatiently leaf through the book, looking for the explanation why this title. And here it is, I’ve found it. Poetas de Megafono (Poets of the Megaphone) is a group of feminist poets who work on the literary fringes of Mexico City. They meet at a café and read poetry through a megaphone. We usually associate megaphones with public protests, but what’s the point of reading poetry through such a device? The point is that in the social sphere women are usually unseen and their voices unheard so this way of reading poetry is the poets’ attempt to be “heard”, to attain a space of their own and to mark it with their art. Poetry spoken through a megaphone resounds like a rallying cry, goes beyond the expectations of polite recitation, becomes akin to protest speeches of disenfranchised workers. . . .

Poetry as emancipation — or is it merely a utopian inscription? I’ve recently received a book from Germany, titled Forgotten Future: The Politics of Poetry in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It was written in English by a young Bosnian theoretician Damir Arsenijević. His main premise is that poetry has a re-politicising potential, since poetry, as Arsenijević points out, “lends voice and establishes relationships between alternative models of subjectivisation (feminist, gay, queer) and new, mutual solidarities, while at the same time opposing their exclusion.” Arsenijević constructs the notion of poetry of difference, i.e. the poetry that acts as a critical voice in relation to a dominant ideology, since male and female poets who voice an excluded element’s position consequently create a new community, while simultaneously creating, as the author emphasises, a politics of hope which opposes the dominant model of manipulation through trauma, in Bosnia and Herzegovina either denied, or mythologized, or medicated. Poetry as an emancipative discourse, says Arsenijević, is above all the poetry written by women, who develop their voices and create a social space for women, but also — which has never occurred before in Bosnian and Herzegovian poetry — for homosexuals. Still, in spite of this poetics of hope, is not a poet, as Faruk Šehić writes, “a tumour on the healthy tissue of a techno-maniacal capitalism”?

I find the name of a friend of mine in A Megaphone, Dubravka Đurić, a poet and critic from Belgrade. I met Dubravka at Women’s Studies in Belgrade nine years ago. She gave me a book then, a collection of poetry and essays by women who reflected on their poetic position called Discursive Bodies of Poetry: A New Generation of Women Poets’ Poetry and Autopoetics. That was my first glimpse into the female poetry writing in Serbia. For a long time Dubravka had organised poetic workshops at the Women’s Initiative Association. During the war both male and female authors who thought of poetry in terms of activism and collective work gathered there. It had been a kind of sanctuary in those not at all poetic years, when young people had become hostages of aggressive politics, unable to travel anywhere as their country had been boycotted. In a rented flat in the centre of Belgrade they had not read their poetry through a megaphone, they had no connection whatsoever with the city’s cultural life. Completely marginalised, they had been reflecting on and revealing links between poetry and politics, those two usually disparate notions. But, as Maja Solar, a young poet from Novi Sad remarks, isn’t any place of speech by definition a political space, therefore, is it at all possible to take poetry as mere transcendence or aesthetic game?

I think about all of this while impatiently leafing through A Megaphone. It is warm in the room, I can see dark clouds through the window, there’s going to be a storm. They aren’t rare here anymore, dear Ana. The days of light drizzle are gone, instead we have brief outpours and in the background, like stage settings, thunder and wind that can uproot a tree or at least blow a few tiles off roofs. But I’m no longer scared of such “storms,” they have become predictable just like the threatening sound of sirens used to be during the war, they don’t yet alarm of chaos, although they announce it. I remember people started ignoring those general danger alerts after a while, because in our parts they didn’t signal attacks or direct aggression. I somehow feel that in recent years people have been trying to forget the nineties, like they never existed, that some even wish to label them as obscene years. I find it strange, I don’t like it when people renounce their former passions, when they try to erase memories. Sometimes everything seems so simple — everybody’s the same, we are all the Balkans barbarians. But what about Americans and all those superpowers, isn’t it possible that were we just pawns in their games? I’m giving it a lot of thought, because lately I’ve felt like the nineties were back: people protesting in squares, shouting through megaphones messages to the “unjust world” which passes judgment on and sentences our generals while the crimes committed by superpowers remain unsanctioned. Our independent state doesn’t in fact exist, it’s been sold out, all that is left are the memories of the dream of independence and a bitter aftertaste.

I think of the great poet Boris Maruna and his beautiful poetry about the loss of the dream of a state, about disillusionment. His poetry is so very different from those cheap, sentimental little patriotic ditties, which haven’t survived anyway. Unlike the authors of patriotic pamphlets, Maruna stresses:

“But a Croatian poet has a right

And a patriotic duty

To say what’s bugging him.”

Another Croatia he so passionately depicts in his verse, imagining it at the end of the world, powerful above graves, equivalent to the Good and Love – there is no such Croatia today. The metaphorical sea upon which it was supposed to rest has withdrawn and Croatia got stranded. As well as the illusion of justice and pride. How to reawaken hope and enthusiasm? Poetry as the politics of hope. . . . Today poetry is read in closed circles, at poorly attended recitals. The lovers of poetry don’t read it through a megaphone but withdraw into the intimacy of their homes. Squares are no longer agorae. Can this be changed, even though we have already lost our pride? Maybe there remains the strength to take a megaphone, to show our dignity and defiance?

I read Celan writing about black milk and black flakes: “There isn’t anyone anymore to mould us of soil and clay, to talk of our dust. . . .” Ana, I feel like quoting so many poems by so many poets, I feel like saying them at the top of my voice in the middle of the main square, among the crowds of people carrying bags with groceries. While I’m closing this letter, the sound of a commercial comes through the window, spoken through a megaphone. Cheap fried fish and fun in your town, come, come, says the voice that drowns all others on this Sunday afternoon, alluring through the megaphone.

Well, Ana, all I’ve wanted to say is that the book has arrived, and look where it’s led me. To the true reality. Maybe that’s for the best. Both the calm before the storm and the storm have ended, the roofs are intact, the books are waiting, not yet read, but new meetings can be glimpsed.

Take care,

Darija

A Universe That's Three Inches Tall and Weighs Three Pounds

My parents’ drafty two-story house in Ohio contains approximately forty-three gazillion books. At least one bookshelf stands in every room — hardcovers lined neatly along family room built-ins, rows of children’s classics in the attic. Glossy art books squat on top of sofa tables; literary journals rest facedown on bathroom counters. Nightstands, toilet tanks, the pool table — everything is a bookshelf. An antique hutch in an upstairs bedroom comes particularly to mind, a piece of furniture so overloaded with my mother’s ecology textbooks that it looks about to give out, as if to say: C’mon. No more.

My parents’ drafty two-story house in Ohio contains approximately forty-three gazillion books. At least one bookshelf stands in every room — hardcovers lined neatly along family room built-ins, rows of children’s classics in the attic. Glossy art books squat on top of sofa tables; literary journals rest facedown on bathroom counters. Nightstands, toilet tanks, the pool table — everything is a bookshelf. An antique hutch in an upstairs bedroom comes particularly to mind, a piece of furniture so overloaded with my mother’s ecology textbooks that it looks about to give out, as if to say: C’mon. No more.

Even the unfinished half of my parents’ basement — concrete-floored, hairy with cobwebs, fringed with venerable toys and raccoon traps and dusty brewing supplies — carries books in its corners. And it was there, one afternoon when I was twenty-two, home from a year in Colorado working as a grill cook, that I stood in front of an old file cabinet surveying the titles stacked on top.

These were my brother’s retired college books: Norton poetry anthologies; Joyce’s Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man; The Harper American Literature, Volume 2. I was leaving for New Zealand in the morning, to live out of a backpack for seven months, and I had traveled overseas enough by then to know the importance of choosing the right book. The last thing you want is to find yourself five miles above the Pacific, fifteen hours left in your flight, with “Soaring, shivering, Candace inquiringly asked . . .” in your lap.

In the center of the stack a teal spine about three inches high drew my eye. The thickest of the lot. The Story and Its Writer.

I lifted the book down. Sixteen hundred onionskin pages, one hundred and fifteen short stories, three pounds. The stories were arranged alphabetically by their writers: Chinua Achebe to Richard Wright. Such a book would be absurd for backpacking.

And yet, as I held it, the book slipped open to an early page as if under its own power. I read, “Upon the half decayed veranda of a small frame house that stood near the edge of a ravine near the town of Winesburg, Ohio, a fat little old man walked nervously up and down.”

Sherwood Anderson. One sentence. It was enough. I lugged the book upstairs and wedged it into my carry-on.

I landed in Auckland and boarded a ferry and decided to hike the circumference of Great Barrier Island, a remote, windswept protuberance of bays and hills in the Hauraki Gulf. I bought potatoes, four sleeves of Chips Ahoy, a can of tuna, two pounds of noodles, and a can with a picture of a tomato on it that said Tomato Sauce. I bought white kitchen trash bags: one to keep my sleeping bag dry, another inside which to sheath the three-pound brick of The Story and Its Writer.

For my first seventy-two hours on that island it rained every minute. On my third night — I hadn’t seen another human being in two days — a storm came in and my tent started thrashing about as if large men had ahold of each corner and were trying to shred it. Sheep were groaning nearby, and my sleeping bag was flooding, and I wanted to go home.

I leaned into the little shuddering tent vestibule and got my stove lit. I started boiling noodles. I carefully cut open my can of tomato sauce, anticipating spaghetti. I dipped my finger in. It was ketchup.

I almost started crying. Instead I switched on my flashlight and opened The Story and Its Writer. For no reason I could articulate, I began with “Walker Brothers Cowboy,” by Alice Munro.

By the second paragraph the tent had disappeared. The storm had disappeared. I had disappeared. I had become a little girl, my father was a salesman for Walker Brothers, and we were driving through the Canadian night, little bottles in crates clinking softly in the backseat.

Next I flipped to Italo Calvino’s “The Distance of the Moon.” Now I was clambering up a ladder onto the moon. The last page left me smiling and awed and misty: “I imagine I can see her, her or something of her, but only her, in a hundred, a thousand different vistas, she who makes the Moon the Moon. . . .”

Then I lost myself in the menacing, half-drunk suburbia of Raymond Carver. Then Isak Dinesen’s “The Blue Jar.” The line, “When I am dead you will cut out my heart and lay it in the blue jar” is still underlined — underlined by a younger, wetter, braver version of me — as I sit here in Idaho with the book almost twenty years later, warm and dry, no ketchup in sight. I press my nose to the page: I smell paper, mud, memory.

When I eventually stopped reading that night, and washed back into myself, I had eaten two entire sleeves of Chips Ahoy. The rain had stopped. I unzipped the tent door and stepped back onto Great Barrier Island. The stars were violently bright, electric-blue. The Milky Way was stretched south to north. Orion was upside down.

For seven months I carried The Story and Its Writer through New Zealand. I hiked my way from the tip of the North Island to the bottom of the South Island and Nadine Gordimer came with me; Flannery O’Connor came with me; Tim O’Brien came with me. On a sheep farm in Timaru, John Steinbeck whispered, “The high grey-flannel fog of winter closed off the Salinas Valley from the sky and from all the rest of the world.” In a hostel in Queenstown, Joyce whispered, “His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe.” In a climber’s hut beneath the summit of Mount Tongariro, John Cheever whispered, “Is forgetfulness some part of the mysteriousness of life?”

Maybe we build the stories we love into ourselves. Maybe we digest stories. When we eat a pork chop, we break up its cellular constituents, its proteins, its fats, and we absorb as much of the meat as we can into our bodies. We become part pig. Eat an artichoke, become part artichoke. Maybe the same thing is true for what we read. Our eyes walk tightropes of sentences, our minds assemble images and sensations, our hearts find connections with other hearts. A good book becomes part of who we are, perhaps as significant a part of us as our memories. A good book flashes around inside, endlessly reflecting. Its shapes, its people, its places become our shapes, our people, our places.

We take in a story. We metabolize it. We incorporate it.

Imagine you could draw a map of all the experiences you’ve had in your life, and superimpose it over a map of all the books you’ve read in your life. Here you worried your daughter was failing out of school, here you gave a nun a stick of chewing gum, here you saw a man dressed as a referee weeping in a Honda Accord. And here a boy in an egg-blue suit handed you an ornate invitation to a party at Jay Gatsby’s, here you met the harpooner Queequeg at the Spouter Inn, here you floated a stretch of the Mississippi with a slave named Jim. Here you crouched in a tent in the rain and read Isak Dinesen’s “The Blue Jar” for the very first time.

Everything would be intertwined; everything would transubstantiate. There would be your life, your memories, your loves and doubts. Then there would be the faint tracery of the lives of your parents, your grandparents, their parents. Then there would be your dreams. And then there would be all the books you have ever read.

I spilled hot chocolate on The Story and Its Writer. I dropped a corner of it in a river. I brought it back across the Pacific and went to graduate school and used it to write literature essays and then to fumble through my first efforts as a teacher. And now I have my own house, my own dozen bookshelves, and the big teal spine of The Story and Its Writer sits on one behind my desk as if waiting to fall open again. If I look at it long enough it seems to pulse.

We are all mapmakers: We embed our memories everywhere, inscribing a private and intensely complicated latticework across the landscape. We plant root structures of smells and textures in the apartments of lovers and the station wagons of friends and in the backyards of our parents. But we are readers, too. And through stories we manage to live in multiple places, lead multiple lives. Through stories we rehearse empathy; through stories we live the emotional lives of other people — people in the future, people in the sixteenth century, people living in Pakistan right now. We fall, we drift, we lose ourselves in other selves.

What I have learned and relearned all my life, what I learned growing up in a house overspilling with books, what The Story and Its Writer taught me, what I relearned last night reading Harry Potter to my five-year-old sons, is that if you are willing to let yourself go, to fall into the dazzle of well-made sentences, each strung lightly one after the next — “Upon the half decayed veranda of a small frame house that stood near the edge of a ravine near the town of Winesburg, Ohio, a fat little old man walked nervously up and down.” — if you live with stories, you will never be alone.

__________

Editor’s Note: “A Universe That’s Three Inches Tall and Weighs Three Pounds” first appeared in Bound to Last: 30 Writers on Their Most Cherished Book, edited by Sean Manning and with a foreword by Ray Bradbury.