How It Began Before It Ended: An Excerpt from WITHOUT SAINTS by Christopher Locke

Without Saints is a breathtaking journey to rediscover hope between the ruins: Poet Christopher Locke was baptized by Pentecostals, absolved by punk rock, and nearly consumed by narcotics. Like Denis Johnson’s propulsive Jesus’ Son, Without Saints is a brief, muscular ride into the heart of American desolation, and the love one finds waiting for them instead.

It was two a.m. The Jetta was parked at the curb and I sat in passenger seat, top down. I felt vulnerable in the dark, uneasy with the city’s brick tenements and low sound. Directly overhead, a streetlight flickered like a dying brain. It was humid and I was dressed in shorts, a black t-shirt. I thought about my wife and daughter asleep back home and shifted my weight; my thighs stuck to the leather seats.

I replayed the evening in my head: After dinner, I finished grading my students’ papers on Thoreau’s theory of needs vs. wants and reread five pages of Marquez’s 100 Years of Solitude for another class. I changed Grace’s diaper and handed her off to Lisa, kissing them both and saying I’d be back by 11:00 at the latest. I went to my car, did four bumps of coke off the house key, and squeezed my eyes shut until the stinging passed.

When I arrived at a party in town, I had some whiskey, a little more coke, and then another whiskey. A white kid with dreadlocks got angry because all the tiki torches outside made the lawn resemble a landing strip, burning a symmetrical pattern that made him furious somehow. He pulled them out of the ground, one at a time, and threw them sputtering into the pool. A glass table followed.

That’s when Billy showed up. And what we wanted was only twelve minutes away. We would look for Psychs again. My heart raced. On the way, we drank beer from red plastic cups and talked about our students; we worked at the same school. The latest batch of kids seemed more docile, Billy said. I mentioned how much I liked the new boy from Jersey and all his mad energy, the love for Emerson he professed in my English class. A quarter of the students we worked with were at the school for drug abuse, the others had social/emotional issues, learning disabilities, or a combination of all three. We were viewed as one of the best therapeutic boarding schools in the country. We counseled kids in three-days-per-week groups. Just the day before, I sat across from a girl and spoke in a soft tone as she held her head in her hands and sobbed. Her long red hair fell around her wrists like spun fire. “I can’t believe I’m here,” she choked. I know, I said. I know.

At graduations, I was always a favorite to speak on behalf of a graduating student. For example, I discussed how hard it’d been for ___________, that he’d overcome massive trauma. Back home, he saw someone get tied to a tree and then set on fire for not paying a drug dealer. The sound of that boy screaming woke him up every night. This young man learned, I said, to love his family, and himself, again. At the end of the speech, as with all my speeches, I cried. The student cried. His family and the other well-dressed families cried. “You can do this,” I said. We embraced and then, bravely, he went back into the world.

We found Psychs where we did last time, hanging out in front of the small, withered park downtown. He wore a red Chicago Bulls jersey, cargo shorts and was sitting indifferently atop a cement ledge. I don’t think he remembered us. As we drove him to the place, Billy asked if I could front the money for the heroin. I said I didn’t have the money, thought he had it.

“What,” Psychs said from the back. “You ain’t got the fuckin’ money?”

“No, no, we’ll get it,” I promised. “Where’s that ATM machine around here?”

The last time we did this, which was also the first night we ever met Psychs, we managed to do the exact same thing: try and score heroin without remembering the money. “It’d be a bad night to get knifed,” Psychs said then, and I pictured a cartoon Arabian sword being pushed through the seats and into our backs, Psychs rolling our stupid corpses out onto the curb. “Stay in the suburbs,” he’d say as he drove off in the Jetta.

This time, after collecting one hundred dollars from the ATM, we pulled up in front of the apartment and Billy turned to Psychs. “Don’t give us any of that white boy shit,” he said. “We want the normal dime bags, ten of them.”

“Hey, don’t fucking talk to me,” Psychs said. “Just give me the money.” He took the five twenties, quickly exited the Jetta and crossed the dark street, disappearing like a spider down a flower’s throat. I was starting to feel hung over and the coke had worn off.

Silently, Billy and I waited ten minutes.

“That motherfucker better not screw us,” Billy said. A car moved softly down a cross street, left no evidence that it had ever been there.

“Fuck it. I’m going in.”

“In? In where,” I asked.

“Don’t worry, I’m just gonna see if he’s in the stairwell or something.”

Billy left and I sat in his Jetta alone.

I kept waiting for the police to roll up behind me with their spotlight blinding the mirror, their careful approach to my door as they asked to see my hands.

I could feel sweat prickling the back of my neck.

Someone came out of the building and walked with great purpose towards me.

Billy opened the door and hopped in. “Hold these,” he ordered. I looked at my hands and counted ten small plastic bags. He started the car and we drove off.

“I already had a taste,” he said, sliding the Jetta smoothly into third gear. “It’s fucking amazing.”

And I believed him because what other choice did I have?

Fragile Threads, from Earth to Sky: A Conversation Between Cindy Rinne and Toti O’Brien

Cindy: The story looks at gay rights, women and those identifying as women having a voice. Although the story is set in the distant past, the issues are current.

Toti: Mine is not a story of flight, but it's a story of long distance, of the courage it takes to part from one's roots while still remaining, somewhere, connected.

Cindy Rinne creates fiber art and writes in San Bernardino, CA. A Pushcart nominee. Her poems have appeared in literary journals, anthologies, art exhibits, and dance performances. Author of: The Feather Ladder (Picture Show Press), Words Become Ashes: An Offering (Bamboo Dart Press), Today in the Forest with Toti O’Brien (Moonrise Press), and others. Her poetry appeared in: The Journal of Radical Wonder, Mythos Magazine, Verse-Virtual, and others.

*

Toti O’Brien: Cindy, I remember when I first heard you read from The Feather Ladder. You were handling the very first copy! The book had just been released. It must have been the Fall of 2021—of course, we were grappling with the pandemic, trying to keep our creative souls and hope alive. I was sitting on the floor of the gallery where your reading took place in conjunction with an art opening. I recall being literally carried upwards by both your imagery and delivery, lifted in a world magical and mysterious that defied gravity. In a landscape of intermittent lockdowns and endless isolation, your aerial verse invoked the idea of escaping the labyrinth from above.

Can you briefly explain the core idea of this book?

Did you actually conceive it during the pandemic? If not, did the pandemic influence its development or its final shape?

Could you say something about where the original impulse came from?

Cindy Rinne: This novel in verse is a coming-of-age story for The Feather Keeper. He is sought out by a group of birds to help them fulfill their dream. He also discovers his mysterious origins because of this quest. Prophecies weave through the story for The Feather Keeper to be fulfilled as he chooses to take this journey.

Owl responded, Owl magic to protect your skin. It will be a night to your fingers.

The original story, which was longer, was conceived several years before the pandemic. The only effect the pandemic had was that the publisher delayed publication until things opened again.

The original impulse came from an idea about a group of birds speaking with The Feather Keeper about their idea to build a ladder reaching from earth to the sky. Then humans could get off the ground and out of their routines.

I made up this myth based in Neolithic times. In the story several times, their new idea receives opposition because there is fear of change. There is also support. As the journey continues, several characters who are not birds help them and The Feather Keeper. They meet with Sitka Spruce, Thunder Sun, Clear Sky, and Stone Woman.

A year later with various versions of COVID, Pages of a Broken Diary is launched in the same gallery captivating the audience. Your delivery is passionate. Although I know you well, there is much to discover in this book. Can you talk about the form in this book? Do you see it as a memoir in fragments through prose or short stories? Why not poetry?

This book seems to go deeper and is your most vulnerable. “I am an orphan at soul.” The origins? Why now?

TO: Thank you, Cindy. “There is much to discover,” is probably the best comment a book could wish for! I see Pages of a Broken Diary as a collection juxtaposing different “formats” and “tones” rather than different “genres.” Some “pages” are clear, memoir-like narratives. Other pages are indirect, elusive. Some are very brief and read like prose poems. This contrast of voices and moods is deliberate. For me, it echoes the kaleidoscope of memory—the way life and its complexities speak to our mind/heart when we reflect on our past.

The book “reads as a memoir” because it strongly focuses on childhood and coming-of-age, family and relationships, motherland and displacement. Still, it doesn’t trace a life story, and the margins between fiction and nonfiction are never defined. My intent was to gather into a cohesive whole my reflections in the above-mentioned areas, delving into them with whatever means I could handle—thoughts, feelings, recollections, hypotheses, sheer imagination, irony, paradox, the lyrical, the documentary, you name it—and then offer to the reader not the result of my questioning, but the questioning itself.

I would think of a memoir as a detailed photograph, with recognizable scenery and portraits—sometimes, as one of those collages juxtaposing many small pictures—sometimes, maybe, as an album one could leaf through. Pages is none of this. Imagine it as a scatter of incomplete, blurred snapshots. Some of them might be distinct, and you seem to recognize this or that—but in the next one the same face is blurred—in the next one, the character or the landscape or the epoch have changed. Think of it as a bunch of puzzle elements sparse on a coffee table. The puzzle must be assembled, and each reader will do it in her unique fashion.

Origins, you say. I love how you simply speak the word, how you just pose it there. Are you asking me why I look back? What I am seeking? Let me ask you first, then… Why did you made up a myth based in Neolithic times?

CR: I decided to push the story back in time when community just began to be a concept and tribes with a chief were starting to form. The Neolithic culture includes farming and the use of metal tools. This was a time when the earth, goddesses, and the stars were honored. We need to bring this back. They wore animal skins. Cave paintings show hunting. I could include hyena and lynx.

The Feather Keeper talks with animals instead of hunting or farming. He’s still a nomad. This character didn’t begin as a Two-Spirit who embodies both the masculine and feminine. I discovered this term at an art exhibit of photographs after the myth had been written. It felt right. He probably would have been accepted back then, but LGBTQ Americans and beyond remain vulnerable to violence and hate. I write ancient / present and brought issues of today into the story.

The book is about social justice, courage, and magic. Myths last because of truths contained. I am a storyteller. Most of my poems contain a story. Sometimes I tell the story over several poems like this novel in verse does.

The style in Pages of a Broken Diary is conversational. Unpolished. Raw in places and lyrical in others. I feel I am with you in the push / pull of uncertainty, a timid present. How spontaneous is your writing? Do you think this allows the reader to bring their story easily? Is this important to you?

TO: As you say, the style in Pages is sometimes conversational, sometimes lyrical. I would not say unpolished because, as an ESL writer, polishing for me is a must—it needs to be agonizing, relentless. But, yes, my first drafts are spontaneous, unplanned, uncontrolled. To me, that is the only way to let “row” and “vulnerable” freely emerge. When they do (boldly show themselves in the nude) they speak to the reader in a different way. Closeness to the reader is important to me. I seek for a dialogue to be established, as authentic as possible, even if mediated through the written page. When I write in a conversational mode I am truly speaking with you, whoever you are. When I withdraw into the lyrical, elusive, non-linear, I am inviting you to behold a monologue happening in a “public sphere of privacy.” I am alone, but the spotlight is on, and you are welcome to witness the “push / pull of uncertainty.”

I firmly believe that the most vulnerable, the most open is the writing, the most it allows readers’ feelings and stories to resonate and emerge in response. And that is the whole point, is it?

You have mentioned “fear of change” as one of the motifs in your book. It is what creates obstacles that need to be overcome in order to build the ladder. But your novel is also permeated by the opposite force, a desire for change, which finally prevails. I wonder if “a desire for change” in the present is what prompts you/us to look back, as if wondering, “how did we get here?” As if, gazing at the past with clear eyes, we could see what we wish to keep and what we don’t want to repeat. Is there something in particular that your book sets to change, might be able to change?

CR: Opposition comes from those who say, Humans were not meant to fly. This can include the idea of are dreams possible? When my first book was published, I realized I was an author. A dream to have a book barely seemed possible. This dream included community from critique sessions to poetry readings. There are many allies in this story.

The ego rises up and says, You are not a good enough writer. Do people care about myth? On the other hand, others can be jealous or try to sabotage. The ladder builders face destruction but learn determination. For me it means a lot when a story or poem touches one person. You and I have discussed the power story holds.

It takes courage to follow your dream and to navigate the unknown. Pushing through the fear is a test for the birds and The Feather Keeper. He says, I will climb when no one else is willing. Recently, I decided to do performance poetry. I love making the writing real in a different way using props, costumes I make, and the movement of my body. In The Feather Ladder, he takes a stand. Opposition comes in the form of power struggles. The Feather Keeper acts in the balance of knowing when to negotiate, be humble, and when to be bold. He keeps the focus of the bird’s dream. In the process, he discovers what is important.

The story looks at gay rights, women and those identifying as women having a voice. Although the story is set in the distant past, the issues are current. I look at the situations of climate, ecological, political, and cultural chaos today. Even think about how this could be a banned book like the feather ladder falls apart. Then I wonder if I/we can find a gift to share with others like The Feather Keeper did? Can we work together to bring change and follow our dreams?

We weave worlds magical and mysterious and defy clear formats. Even in what appears to be very different books, there’s links. Discuss.

TO: Yes, there are definitely links between these two books! Otherwise, we probably would not be having this conversation. I can think of two main connections, right away. One is almost obvious. As per our visual art, we both build books out of fragments, juxtaposing bits and pieces instead of embracing a unified, fluent narrative. As per our visual art, we both use shards that are asymmetrical, different in texture and size. I have discussed my frequent and deliberate changes of tone, POV, format. The building blocks of your book are all poems, but they vary as well. The story is told by a polyphony of voices, the POV constantly shifts, even the font/format does. It seems that we both like sharp angles, such as the zigzag point you frequently use in your textiles, or my ripped shreds of papers.

Another, very strong similarity pertains to contents. Both of ours are coming-of-age story, though “age” is not insisted upon—a detail that rather likens them to tales of initiation, testimonials to a process of inner growth. Mine is not a story of flight, but it’s a story of long distance, of the courage it takes to part from one’s roots while still remaining, somehow, connected—as it happens to the unnamed character of “Her Kind,” which dreams to be attached to a pole and runs until sheer momentum lifts her from the ground. Though she’d like to be a bird, she knows she’s not one. Still, she stubbornly enjoys her parcel of levitation.

After all, my book ends on something aerial as well: the airmail letters, light as feathers, going back and forth across the Atlantic, “fragile threads creating the legend, stretched over oblivion.”

Checklist, Recipe, Yellow Brick Road: A Review of Pamela Wax's WALKING THE LABYRINTH

Pamela Wax, whose life is a found poem, “pretends to be who she is, tries to be normal, spills words all over herself and loses her names”—an apt description of so many poets.

Pamela Wax is a poet-rabbi and while she produces first-rate art, bibliotherapy also appears to be a priority. Walking the Labyrinth is an apt metaphor for this odyssey. While this book purports to be a series of elegies, it is also a deft memoir that avoids the heavy-hand of an incessant first person. Its emphasis is less memoir than spiritual autobiography, but the occasional first person explorations subtly hold a place for both her own idiosyncrasies and struggles as well as her readers: she creates space for your I and for my I.

The persona “pretends to be who she is, tries to be normal, spills words all over herself and loses her names”—an excerpt from “The Woman Who: A Found Poem,” says it all and says it best. We are offered frequent glimpses into the panoplies of pain associated with this quest for virtue—often in tandem with the duties of family and tribe. The grief and consequent suffering accompanying this attainment of virtue is resolutely probed.

Her elegies for her brother Howard and many others act as both catalyst and muse. Her awareness may invite us all to stop working so hard at virtue, but also reveal Wax’s prime compulsion—a longing for a guaranteed “checklist, a recipe, some yellow brick road,” a map or atlas revealing the important “to do’s,” all of which reflect her need for a world in which she can attain righteousness—where she can be safe and in control—a world in which she locates the proper path to attaining goodness. This is often followed by worry—the need not to get it wrong. It being life, with all its attendant uncertainties: all the self-blame, remorse & grief, especially the guilt inherited by those who sacrifice themselves for so-called higher or holy quests: our spiritual leaders. Our gurus, priests and rabbis.

In a moment of insight Wax describes a cartoon caterpillar on a couch being advised by her butterfly therapist: “the thing is, you really have to want to change.” This comical image and dialogue triggers a listing of internal guilt-trips. She goes on to detail minor masochistic behaviors she indulges in, in order to undermine any sense of entitlement or right to claim grace. In this psychic no-win situation her sense of humor & attempts to reach for optimism are laudable, yet the pathos remains notable.

Wax defines herself through her tribe, yet avoids religious zealotry; however, details about Judaic traditions might distance some readers who are not familiar with a diction that includes words like kvelling, shomer, hora, and kaddish.

A poem that helps clarify cultural differences is “I Am Not Descended from Stoics Like Jackie O.” as she explores the reality of being “descended from Eastern European Jews who turn their prayers towards a Wailing Wall because the danger & despair are everywhere and eternal and what else did they know to do?” Is this book Wax’s personal wailing wall? Possibly.

Occasionally Wax slips into manifesto, but still manages to hold fast to her suffering: “when my guilt takes a form other than flesh. I mix it with naked rage because never again is pitched capriciously in the ominous night tent of the world—feeling all this almost guiltlessly on sunny days.”

Her obsession with virtue is portrayed in her gently self-mocking poem “I Keep Getting Books About Character.” As she reads and rereads many translations of Paths of the Just & Duties of the Heart, we are treated to a light-hearted bit of satire, best illustrated by a sign in her office that reads:

I want to be a better person but then what? one queries. A much better person?

She romps often with sound and enjoys occasional rhyme in her pithy description of her readings of “Medieval tomes in pious tones.” Her zig zags between despair and humor keep her afloat and help the reader process this confessional.

The format varies occasionally as in her odd first poem “Howard” which she divides into two sections: part one is titled “I. How” and part II. is “Ward.” This playful character sketch introduces us to the book’s central elegy for her brother Howard, a suicide. She returns to this formatting later in the book.

Walking the Labyrinth is the mother of all elegies—it holds too many to remember or list. It presents us somehow with a life lived primarily through a lens of loss but without the anticipated and attendant nihilism. It is not an easy read but well worth the effort, even if your life is not steeped in family ritual or religious legacy. Dive in. See if you can swim. It may be best to prepare for reading a book of elegies by not being prepared—if preparation is even possible. Let its stream of consciousness flow. Drop control needs. Practice what the poet finds so difficult. Relinquish her needs for “checklist, recipe and Yellow Brick Road.” Step into her journey. I feel fortunate to have met and eventually to have groked my first rabbi, Pamela Wax. Join her, as she invites, us, much “like Rumpelstiltskin,” to “weave seaweed into song.”

Something is Afoot: An Interview with Andrea Ross, Author of UNNATURAL SELECTION: A MEMOIR OF ADOPTION AND WILDERNESS

Some of it is recklessness, the recklessness of youth, and also the adoption loss of self. I felt like I needed to pitch myself against the elements (snaps her fingers) to feel alive, to prove that I was worthy of walking the earth, so that was a big part of it, like testing myself against the elements, what can I do, how far can I go with this till I feel like I am deserving, like I'm worthy somehow?

Andrea Ross’s debut book, Unnatural Selection: A Memoir of Adoption and Wilderness (CavanKerry Press, 2021) explores the rewards and dangers of exploring the natural world, living an unconventional life, and questing for ancestral identity. This suspenseful read is a surprising and poetic yet accessible narrative. As an adoptee, I was attracted to the subject matter, and discovered an elegantly structured and nuanced book that relies on pacing and imagery. It is a memoir devoid of confession and cliché, a feat as deft and daring as the two interconnected experiences Ross describes: living as an itinerant back woods nature guide, while searching for clues as to her family of origin. The Grand Canyon and the canyon of sealed records mirror each other, and she describes facing them with the same curiosity and fortitude.

In the last year, adoptees have made great strides in recentering the adoption narrative to focus on the people most affected and most ignored: adoptees themselves. Writers, filmmakers and podcasters have gone public with meaningful works addressing an experience that the culture both glamorizes and illegitimizes, one that makes detectives out of ordinary citizens as we seek information and connection that the rest of the world takes for granted: ancestry, heredity, and family. I took special interest in discussing these powerful shifts in perspective with Ross, as much as discussing her craft.

We spoke in person on March 26, 2022, during the last hours of AWP 2022, after she moderated a panel called, “Each Book Another Me: Mapping the Progression of Self Over a Career.” A mix of fatigue and buzz, adrenaline and soul, filled the halls of the Pennsylvania Convention Center, as friendly maintenance workers moved the loiterers like us toward the doors.

During the panel Ross introduced her work this way: “My first book is called Unnatural Selection: A Memoir of Adoption and Wilderness… it maps the human need for belonging both from an adopted person’s perspective for belonging to community, belonging to other people but also belonging to landscape: the idea of landscape as a surrogate for lost family, landscape as the body of the beloved and landscape as a living breathing entity which we are in relationship with.”

*

KFK: So in the panel you reveal that this memoir started as a book of poems.

AR: I can send you some of them if you want to take a look at how the poems and the prose interface with each other.

(The corresponding poem and prose excerpts are at the end of this interview.)

KFK: I would love that. It was interesting hearing you talk about how, because of audience and message, that it had to turn into prose.

AR: I'm glad you caught that. My memoir has a certain reader in mind. I wanted to explain to people who aren't adopted or haven't been touched by adoption, the particular brand of loneliness that adoptees experience, especially when they're from closed adoptions in which they're not allowed any information about their origins. The book I'm working on now has a completely different audience and I think that as a writing teacher we talk all the time about who is your target audience? What kind of background information can you assume they have? What do you need to tell them? What kind of language or jargon or vocabulary do you use?

I thought, “I really need people to get the message and it's not coming across in poems even though I just spent two years working on them.” But it took a lot longer than that to write the book as it turned out.

KFK: How long did it take?

AR: I would say beginning to end probably 10 years. I was also raising a small child and trying to launch my career as a teacher and so I didn't have a lot of time to devote to it, but also a lot of it was just really hard stuff to go into and I had to pace myself because I would just get sad and I didn't want to go too dark and not be able to pull myself back out. I would set aside time for writing the really hard stuff and try to compartmentalize, so yeah it took a long time.

KFK: So you saying, “This is going to be really hard to write…” I have to say I had this book sitting on my nightstand for a week thinking, “This is going to be really hard to read…” because as you know I'm adopted, too.

AR: How did you find it when you did dive into it?

KFK: I felt… lightened. It was a great feeling… So tell me about your three semesters with poet Lucille Clifton.

AR: I mentioned in the book I was not an English major or a creative writing major as an undergrad, but I did like to write and so I took an intro to poetry class. Once you've taken the intro poetry class at UC Santa Cruz, you were allowed to try to get into the advanced poetry class, but you had to submit a portfolio to be considered. I imagine there was some pressure on Lucille and the other professors teaching that advanced class to only accept people in the major, but she said she would just kind of meditate on people’s manuscripts and pick the ones that she felt that were people who had something that needed to be spoken, and somehow that happened three times.

She's sort of a patron saint because I don't know what I would have ended up doing if I hadn't had the boost from mentors like her. It really was kind of like sitting in the room with a prophet because she would just say these things that were so profound. She was such a national treasure and she touched so many people. I just felt super lucky to have had that time with her.

KFK: Did you read Guild of the Infant Savior: An Adopted Child’s Memory Book by Megan Culhane Galbraith?

AR: I did.

KFK: What do you think of it?

AR: I liked it! Megan and I have been in contact ever since we realized that our books were being published at the same time. I like that hers is so different than mine. It makes me feel more secure that mine has its own niche but interestingly so much of it is just saying something similar, the closed adoption stories of people just really needing to know who they are and not having access to that. Then the next part of the story is if you do search we all seem to have the same fears and hopes, that they (our biological parents) might be dead, they might reject us, they might be the most amazing person… Or we might have the Kunta Kinte “I have found you!” moment.

We all have that range of fears and hopes around reunion, but then she had a completely different experience with finding her natural mom than I did. They were really into each other at first, and now they're estranged. Mine has been much more even keeled than that. I never felt like, “Oh now I understand why I am who I am.” I didn't and I don't really see myself reflected in my natural parents so much, but nonetheless even though we're super different and have really different politics and values, they're all really committed to being in relationship, even though it's not super close.

I get envious when I hear stories of people who were like “I look just like them.” But in terms of the best possible outcomes, I think I lucked out. I've been in reunion with my natural mom for 20 years. That's pretty unusual. Often reunions run their course in less than 10 years, partly because there's no map charted for that relationship and so it's just really hard to figure it out. I think a lot of times somebody just kind of drops off. It's probably not unlike what happens with some open adoptions these days where people go into it with good intentions and wanting to do the right thing for the child by keeping everybody in contact, but then it gets hard because you're parenting somebody else’s biological child, or you are the biological mom and you are coming to grips with, over and over again, the fact that you have relinquished your child. I think it's similar in an inverse way.

KFK: There’s trauma in both staying in touch or being apart. “Adoption is trauma.”

AR: So much trauma.

KFK: That’s still considered “a theory.”

AR: How's that for those of us who have lived it? We know that it's not just a theory.

KFK: Did you see the documentary Reckoning with the Primal Wound? Are you part of The Adoptee Army?

AR: Yes and yes. Did you get your name on The Adoptee Army list at the end of the film?

KFK: I was late to the game, but when the film gets fully released, I'll be on The Adoptee Army list.

AR: It was so gratifying to see my name and to see so many names on that list.

KFK: It's growing and growing.

AR: Such a good idea that she (director Autumn Rebecca Sansom) had to just make that list in the credits. I was telling a friend of mine about it recently. She said, “It kind of gives me chills… it sounds like the Vietnam memorial, except that was everybody who died and these are the people who lived, but are lost…” So it’s a different kind of reconnection…

I found out about that film because I was asked to be on the podcast called Adoption: The Making of Me, which has been going for about a year. The premise is it's two adopted women who are about my age, mid 50s, who have been friends for a long time and they decided to do a podcast in which they would each read a chapter of Nancy Verrier’s The Primal Wound, discuss it on their podcast and then bring in a guest whom they would interview.

They brought me on and said, “We saw that Nancy Verrier blurbed your book. How in the heck did you do that because we want to contact her!” I totally cold called her and she was just so generous. They're like, “We want to bring her on because we're reading her book!”

They contacted her and she got back to them eventually and she told them that this Reckoning with the Primal Wound film was happening, and they told me.

Just like you mentioned in your email, something is afoot. I don’t know what it is yet, I am really looking forward to finding out, but something is afoot with the adoptee community and just with adoption in general and the way that people are talking about it and exposing things.

KFK: My thesis or theory is the idea that The Primal Wound was published in 1993. It was such a groundbreaking book, to acknowledge that infant adoptees had suffered a loss, that we are not blank slates. I started going to Joe Soll’s Adoption Healing Network support group in New York City around that time. I think it's taken us this long to get well enough to tell our stories, to make art, to be open enough. I’m also not sure what it is, but it seems like since the last generation did this work that helped us get well, that's its now our time.

AR: Megan and I are exactly the same age, and the podcast women…

KFK: Me, too.

AR: There's something about this coming of age, into the age of “no fucks left to give.” Like fuck all y'all, I'm gonna speak my truth! There's something about being over 50. Just suddenly, not suddenly, but gradually, we've matured and learned that we just have to live our lives the way that we want to live them and if that means telling hard truths, then so be it. That is really interesting, that we are all the same age.

KFK: The Summer of Love, right?

AR: I thought maybe that was my genesis but my natural mom was so conservative she couldn’t have even known what that was, but she was having sex anyway as people do.

KFK: Surprising who has sex!

AR: Almost everybody, turns out!

KFK: You handled that so well in your book. You left a lot off camera, but we knew you were being pretty wild in many ways. I like that.

AR: People always ask me, “What's it like to have people know this really intimate stuff about your life?” And I’m like, “You don’t know the half of it.” I didn't really want it to be about my sexuality, but part of that was about the search for self, trying to be fulfilled through in relationship with other people, especially dudes, yeah, a lot of bad boyfriends…

KFK: A powerful scene in the book was when you found the wounded hiker. I thought that if this story couldn’t get any more wild and dangerous…

AR: The more time you spend out in the wild the more likely you are to come across the extraordinary, whether it's something really scary like that or something really beautiful… I was squatting to pee in Alaska when I was out backpacking and I looked up and there was a wolf standing there, the only time I've ever seen a wolf. The wolf checked me out and walked away. I never would have seen that if I hadn't been out backpacking in the Alaskan tundra. That happened one day out of the hundred days that I was out there.

KFK: You are so courageous to do these things! I love the outdoors but…

AR: Some of it is recklessness, the recklessness of youth, and also the adoption loss of self. I felt like I needed to pitch myself against the elements (snaps her fingers) to feel alive, to prove that I was worthy of walking the earth, so that was a big part of it, like testing myself against the elements, what can I do, how far can I go with this till I feel like I am deserving, like I'm worthy somehow.

KFK: A great line in the book is, “Participate in your own rescue!” That’s a sticky note on the refrigerator line.

AR: (laughing) That one just got handed to me. The river rafter really did say that and I remember being just puzzled at the time, like how can I possibly participate in my own rescue? I'm sitting here in the Grand Canyon in this freezing cold water, I just got flipped out of a boat. I can't participate in my own rescue and then of course it's just such a direct metaphor for what we do as adopted people as wounded people, people who have gone through traumas. How much do we have to freaking participate our own rescue? Well turns out a lot. Like you were saying about going to the adoption groups and healing yourself, like it doesn't really happen unless we do it ourselves.

KFK: I think if Reckoning with the Primal Wound gets picked up on Netflix or Hulu or HBO then people scrolling will actually learn something about themselves or their adopted family members. It's hard to get someone to pick up a book.

AR: I found it so powerful the way that she was able to field the perspectives of so many different parties involved in the adoption constellation. Just to see a sibling, her bio sibling, grappling with what that meant. To be like, “suddenly I have this sister.” I had the same thing with my half-sister and it's hard for her. I think getting that validated is really important, just as much as it is for our experience to be validated.

KFK: Somebody in the chat room after the Zoom film screening said, “I had a failed reunion! Why do you have to keep telling me Cinderella stories?” That felt like “ouch.” We have to acknowledge our privilege that this reunion worked out.

AR: There has to be ways for people to deal with that. Like what Megan is dealing with. That’s got to hurt. A lot.

KFK: The empty picture frame is in the book more than once. It's very interesting it wasn't just to end the book. She wrote, “I was not allowed to use this photo” under it.

AR: It's so emblematic of the rest of our lives before reunion. We aren't allowed to use that because we're not allowed to have access to our own stinking birth certificate. I just got mine four months ago. I was doing an article about how it's done on a state-by-state basis. It’s a giant mess and up until only like five or six years ago Colorado where I was born did not allow it at all and then the law changed. I was like, I haven't been keeping up on my homework and so I just went ahead and sent away for it and got it. It was weird.

KFK: Did the article find a home?

AR: It was published in The Conversation. What's cool about it is that it gets picked up by lots of other outlets so when I Googled my article after it was published on The Conversation and all these other outlets had picked it up, so it goes out into the world in a way that it's hard for writer of my platform to otherwise do.

KFK: Congratulations on the book and now your article! What’s next for you?

AR: My next book is more joyful and it's about women and friendship and the outdoors, so my target audience is people who want to experience that joy.

*

Andrea Ross did send me two unpublished poems that later became chapters of Unnatural Selection. Here is an excerpt from one, and an excerpt of the chapter of the memoir after it.

The Skull

(This event is referenced in Unnatural Selection’s chapter called “Ruins and Ladders”)

A gratefulness.

*

Nothing exists except the present.

A foothold—

We’re always experiencing a present moment.

sandstone, the Navajo sandstone.

The past and the future are simply ideas.

Footholds in the sandstone’s face: each a fist-

shaped niche, deep as a toe, a couple of knuckles;

We are not subtle enough to have a science of becoming.

a foothold is a handhold.

Nothing is ever one thing or the other.

*

Excerpt from Unnatural Selection: “Ruins & Ladders: Navajo National Monument”:

“In my little tent that night, missing Don, I distracted myself from my preoccupation with the cattle by envisioning the footholds and handholds I’d seen chopped into the gritty Kayenta sandstone during my descnt into the canyon that day. Known throughout the desert southwest as Moqui steps, they are prehistoric pathways, climbing routes carved by the Ancient Puebloans. I knew it was important to leave any archeological artifact alone so that it might be preserved and appreciated by future generations. But were the steps artifacts? All I knew was that they called to me. I desperately wanted to put my hands and feet into their small recesses to see how they fit, to find out where those hanging cliff trails would take me.”

The Whirlwind of Beginning and End: A Review of Our Last Blue Moon

Kris did not have to convince me of their bond; I felt it from the way she wrote, the words Alan wrote that she chose to share again within her own work, and the moments she decided to share with the world. Theirs was a romance that needed no evidence, no verification from the world.

I knew how the story ended before I picked up Our Last Blue Moon—the short version, at least. Alan Cheuse, a widely published author, fiction professor at George Mason University’s MFA program, and the longtime “Voice of Books” on NPR’s All Things Considered, died suddenly and tragically in 2015. In the years following his death, I’ve met Kris O’Shee a couple of times at various literary events in the Washington D.C. area. People at these events who knew Kris, who knew who she was, would tell me, in a low voice like the ones usually reserved for funerals, “That’s Alan’s widow.” The gravity of his loss was clear in their furtive glances, their stares, their whispers—the awkward sympathetic motions made by people struggling with how to deal with a loss.

I never met Alan. I came to Fairfax, Virginia, and the graduate creative writing program where he taught four years after his passing. Still, though, his presence looms large. The Alan Cheuse International Writers Center, founded at George Mason University soon after his passing, constantly puts out great work bringing the work of international writers and translators to a broader audience. They constantly honor Alan’s lifelong passion, as the son of a Russian immigrant father, for gaining experiences and wisdom to broaden his own cultural understanding. Faculty and alumni who knew him talk about him often, remembering their time with him fondly and continuing to share stories, like the way he always kept chocolate in his desk at school, just in case somebody came by and needed a pick me up. Even though Alan has been gone for years now, and the students currently working through the program never met him, he is still very much a part of our educations.

It is because Alan’s spirit and memory permeates every aspect of the writing program at George Mason that I was so excited to pick up Kris’s book. In addition to his teaching and his kindness, one thing that people always talk about is how much Alan and Kris loved each other. Opening Our Last Blue Moon was like stepping into a fairytale, even though I knew the ending was anything but a happily ever after.

From the first chapter, I was swept away. Kris has a skill in writing that many writers practice their entire careers to achieve and that some never master; her writing is genuine, undramatized, brutally, breathlessly real. The craft elements we learn in formal writing courses— narrative distance, pacing, emotional balance—all seem to come naturally to Kris, like she’s picked up these skills through osmosis over decades of spending much of her social time in Alan’s circle of writer friends. She invites you warmly and completely into her life, her story, creating a feeling of a personal relationship with her, one where calling her Ms. O’Shee feels too formal and cold. When Kris starts telling the story, there is no need to imagine how she must have felt picking up the phone to learn her husband had been in an accident. It bleeds through the page.

This raw authenticity never lets up through the whole book. In both the happiest and most tragic moments, Kris manages to walk the line between putting enough power behind her words to bring the reader into the room with her without falling into the melodrama one might anticipate of a debut author. The moment Kris and Alan meet, their first kiss, their first shared apartment in Washington D.C., their final conversation; all of it is imbued with life and careful finesse.

The structure of the book, too, is a testament to how deep their connection went. Oscillating in time, mostly between the week they first met and the final weeks of Alan’s life, Kris shares their picturesque love-at-almost-first-sight meeting at an artist’s retreat right alongside the moments where their love was at its most intense. Kris did not have to convince me of their bond; I felt it from the way she wrote, the words Alan wrote that she chose to share again within her own work, and the moments she decided to share with the world. Theirs was a romance that needed no evidence, no verification from the world. In this way, Our Last Blue Moon is unlike any love story I have ever read.

Ultimately, I walked away from this book wanting to sit down and have a conversation with Kris O’Shee. I wanted to hear more of her stories, learn more of her life and her life with Alan, and to become her friend. The way she tells her story made me feel like I had already made a significant step toward friendship, toward sipping sweet tea on her screened-in Washington D.C. porch chatting and gossiping like old friends. I don’t know that I’ve ever had such a strong wish to really know an author after reading their work, but Kris made that desire encompass me. Her writing is an open invitation into her world, her love, her grief, an experience I found myself not wanting to part with. So, in lieu of tea on her porch, I have recommended this book to anybody I can—young and old, writers and nonwriters, romance lovers and memoir enthusiasts alike—urging them to get a copy as soon as possible so they, too, can feel as I have. While I wait, I’ll just pick up the book and start again.

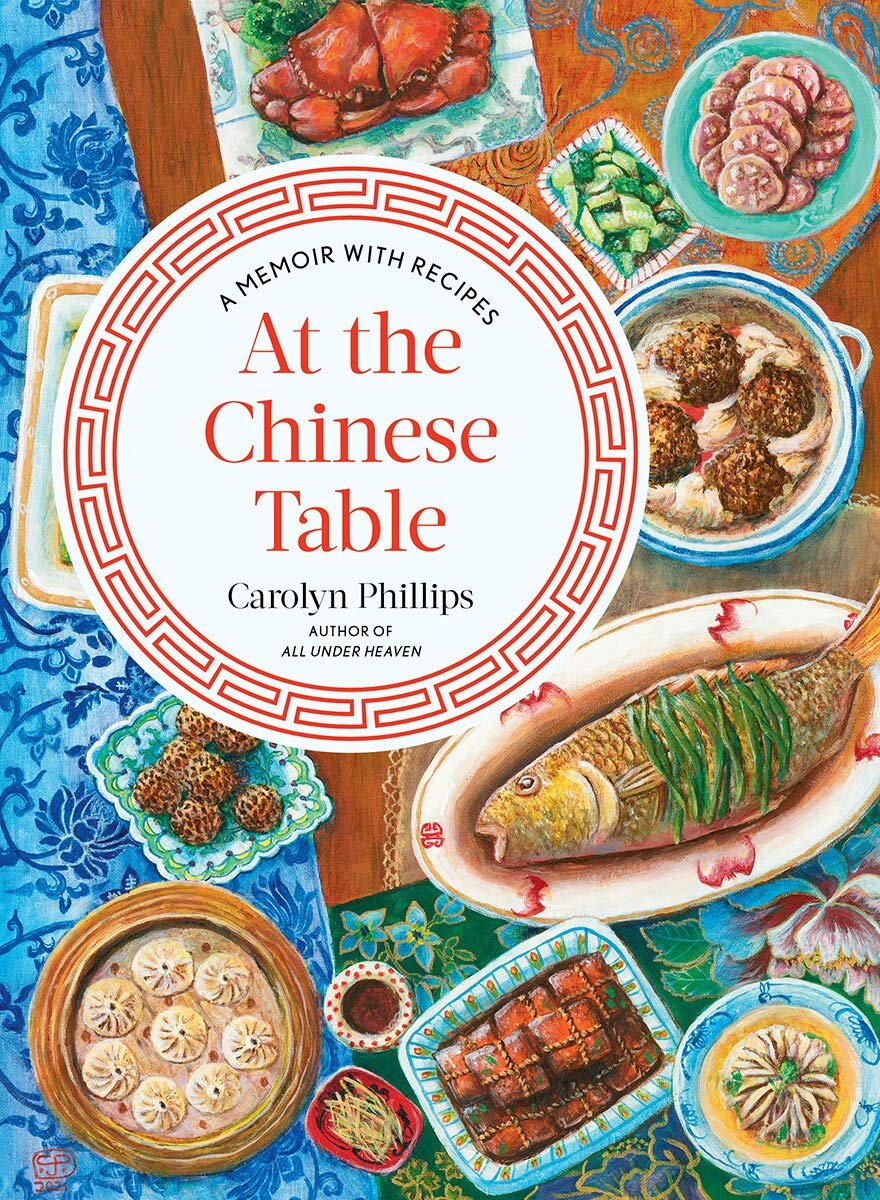

Connecting Through Chinese Cookery: A Conversation with James Beard-nominated author Carolyn Phillips

I hope to not only encourage people to remember the foods and to cook them, but also to appreciate them. You can have a great chef, but chefs need to have a clientele with sophisticated understandings of what is being served to them.

Forty years after she moved to Taiwan, Carolyn Phillips’s first book, All Under Heaven, was a finalist for the James Beard Foundation’s International Cookbook Award and her second book, The Dim Sum Field Guide: A Taxonomy of Dumplings, Buns, Meats, Sweets, and Other Specialties of the Chinese Teahouse, also came out that year. Drawn to her background and the story of her cross-cultural marriage to author and epicurean J.H. Huang, which she discusses in her latest book, At the Chinese Table: A Memoir with Recipes, I recently sat down to speak with Phillips over Zoom.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: When you first landed in Taipei in 1976, Taiwan was at a crossroads. Longtime leader Chiang Kai-shek had just passed away a year earlier and across the Taiwan Strait, the decade-long Cultural Revolution came to a close as Chiang’s nemesis, Mao Zedong, also died. When you got to Taiwan, what did you know about the politics of the region and did you understand what a pivotal time it was?

Carolyn Phillips: I was an oblivious kid. I was just out of college and had no idea what I was doing. I didn't even know why I was really there. I wanted to learn Chinese, but I didn't know what to do with my life. I was like a headless fly with no sense of direction, as my mother-in-law used to say. So, no, I really didn't understand anything and was slowly figuring out what the world was about.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: This was at a time when the United States was in the Equal Rights Amendment era and women were no longer expected to marry, have kids, and stay home right after finishing school. What was your biggest surprise in Taiwan when it came to women's equality? Certainly your mother-in-law was very strong and you learned a lot about the women in J.H.’s family, but was there something else that showed we are all much more alike than we are different?

Carolyn Phillips: At that time it was at the very tail end of the Confucian era and still very much a stratified society where men had all the power. Women had very little say, even over their own children. As I mentioned in the book, if you got divorced your children belonged to your husband. Lots of women suffered and were expected to work for their in-laws.

So I had to modify my behavior because it would be very easy for people to assume I was a “bad girl”. I had to stop smoking and came to never drink. But I’ve always been a feminist. Going to Taiwan was like jumping back into my mother's generation where it was all a one-way street. Men could do what they wanted and women had to toe the line. But in Taiwan I learned not be judgmental and realized I couldn’t impose my views on others. I made good friends with women in Taiwan, though, and they'd tell me their sides of the story.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: Did you see changes in the time you were there?

Carolyn Phillips: Yes. I became fascinated by the feminist movement in China, particularly around the 1911 Revolution. Women began to finally gain certain freedoms and I talk about that a little in my book with my husband's maternal grandmother. Before then, women were absolutely uneducated and had zero rights.

And so I started talking to elderly women in Taiwan. In chapter two of my memoir, I talk to Professor Gao, a feminist. I read many books and tried to figure out what was going on in Taiwan, because they, too, were on the cusp of change. The courage and strength of these women is absolutely phenomenal. Women are now increasingly not marrying in Taiwan, and it's also like that in Korea, Japan, and Hong Kong, where women don't need to be somebody else's daughter-in-law and don’t need to have children in order to be fulfilled.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: Another thing I loved about your memoir is that you include gorgeous illustrations you drew yourself, along with recipes you learned from your time in Taiwan, your travels in China, and from J.H.’s family. It's really a multifaceted book, and it's going to be difficult for me to read more traditional memoirs after being so spoiled by yours. Did you plan to include illustrations from the beginning? You'd already illustrated your two other books, The Dim Sum Field Guide and All Under Heaven.

Carolyn Phillips: My publisher really wanted to have illustrations. I had originally started out with illustrations in my first book, All Under Heaven, because McSweeney's, my publisher at the time, had asked if I wanted to have photographs or illustrations. I asked about the difference between the two, and he said the cost of illustrations was much less, so I could have more recipes. So I said let’s do illustrations. And because I’m a total control freak, I did the illustrations myself.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: Were you trained in art? Your illustrations are so beautiful.

Carolyn Phillips: No, I was never trained in art, officially, although I did take lessons in painting and so forth in Taiwan. I worked at the National Museum of History for five years and we had some of the greatest artists in Taiwan. So I would watch them paint and learned from them. I always loved to draw, although my mom discouraged it. I had my Rapidographs when I was in high school and thought they were the best thing ever. I guess this sort of carried over.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: So with your memoir, it was just kind of a given that you would illustrate it?

Carolyn Phillips: Yes. They really wanted to have illustrations and I think that was part of the sell. They liked the idea that it’s unique. Not too many people illustrate their own books.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: Dim sum is one of my favorite meals. It's also that whole experience you write about: sitting for hours in large dim sum stadiums, sipping tea and chatting with friends or family. Can you talk about how you came to write The Dim Sum Field Guide?

Carolyn Phillips: I had my first great dim sum meal in Hong Kong on Nathan Road not too far from the Star Ferry. I knew this American nun who was living in Hong Kong, and she and her sister nun invited a couple of my friends and me to have dim sum. At the end, we got into a huge tussle over the bill, which of course is very Chinese. So these two white women are duking it out in the middle of the dim sum parlor and everybody's practically taking bets.

I was thrilled by the whole concept of dim sum. When you get an American breakfast with waffles, eggs, and bacon, it's delicious, but after two or three bites you wonder if you want to have forty more bites of the same thing. With dim sum you can slowly go through steamed, pan fried, deep fried, and baked, and everything is totally luscious, and I'm drooling as I speak.

The seed for the book came when I first got that contract with McSweeney’s for All Under Heaven. My editor was Rachel Khong, and she was also an editor at Lucky Peach. She asked if I wanted to write something for their upcoming Chinatown issue. And so we came up with the idea of a field guide—like a bird guide book—with sixteen different dishes. When Lucky Peach had the MAD symposium in Copenhagen, they turned the article into a little pamphlet to pass out. While I was waiting for All Under Heaven to finally get published, I wrote to Aaron Wehner, the editor at Ten Speed Press, and told him what I’d done at Lucky Peach and asked if he’d like to do a whole book on this. And he said, “Sounds cool.”

Susan Blumberg-Kason: That came out the same year as All Under Heaven?

Carolyn Phillips: It came out the same day! Only Prince and I have done that. I’m in a good company with The Purple One. It was a thrill. Ten Speed Press took over the publishing of All Under Heaven because McSweeney’s was going through some issues so they did it in cooperation with Ten Speed.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: So I have to ask this because I'm sure readers will wonder about it. Have you ever been questioned on your authority of Chinese food?

Carolyn Phillips: I've really never gotten any pushback, knock on wood. What I have received is a whole lot of love, especially from the Chinese American community. For example, there was a lady who lived in Central Valley in California and she described these cookies that her grandma used to make. But she didn’t know the name. I went through the many cookbooks I have in Chinese. When I finally found a couple of recipes, I asked her if they sounded like it. After several tries, she finally said that’s it. So if I can help somebody like that reconnect with their family, I just feel like I’m doing something right. As long as you're not approaching it as cultural imperialism and if you're doing it with respect and with love and with humility, I think it’s okay.

My role model has always been Diana Kennedy. I think she’s one of the very few white women who has actually become an expert in her field. Even the Mexican government has recognized her contributions, and she’s received the Order of the Eagle.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: It's good to think about all these things because there are so many benefits to having these recipes and these methods of cooking.

Carolyn Phillips: The reason I wrote All Under Heaven was because the foods that my husband and I loved eating in Taipei during the 1970s and 80s were classical cuisines of China—and there are many cuisines in China—that had come to Taipei. We were the beneficiaries of this and ate like kings and queens many times a week. But when we came to the States, they didn't exist. When we went back to Taipei to eat, these places no longer existed either, because the chefs were passing away or retiring. The younger people didn't know what it was they had had. I hope to not only encourage people to remember the foods and to cook them, but also to appreciate them. You can have a great chef, but chefs need to have a clientele with sophisticated understandings of what is being served to them.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: I think Americans have gotten more interested in food in the last ten to fifteen years. It’s a slow process and books seem a good way to bridge that and to get people interested.

Carolyn Phillips: It's a good beginning. Television is also a good way to go. Anthony Bourdain was marvelous in that way. He had that humility and curiosity I think we all aspire to, where he would eat every part of a warthog, or go into a village and eat whatever they served him, which is absolutely the correct attitude.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: You did everything that Bourdain was known for, but decades before, and one of the things you write about in your memoir is cooking a pig head. Anthony Bourdain would have made that glamorous but you did that for your family and friends.

Carolyn Phillips: A lot of it was to just win over my future mother-in-law because she was a real hard nut to crack. But she did love to eat, so I learned to cook the foods that opened her up and warmed her to me. That was a great stimulus, winning your mother-in-law over, especially when she was a warlord lieutenant’s daughter.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: Did any books or authors inspire you to write At the Chinese Table? And do you have plans for a fourth book?

Carolyn Phillips: I’m actually finishing up my next cookbook. I can’t talk about it now because I don’t have the contract yet. As for food biographies, there are so many wonderful memoirs out there. My first influence was M.F.K Fisher. She writes more sensually about food than anyone I know. Some men don’t like her. I don’t know why, but to me she always spoke to my heart. Even now I can remember her peeling a mandarin orange and placing the segments on a radiator so that the skins would slightly crisp up before she took a bite. That kind of depth of sensuality is phenomenal to me. Julia Child’s writings are wonderful. Han Suyin’s Love is a Many-Splendored Thing is based on her cross-cultural life. There is also Georgeanne Brennan with A Pig in Provence. I filled up my shelves with people, especially women, who went to another country and sort of lost themselves. I’m really fortunate to be on the James Beard Foundation’s Book Committee. We see a lot of really great food writing and we’re so lucky to live in this world where food writing is appreciated. Kiss a food writer!

Susan Blumberg-Kason: I just love that ending!

Carolyn Phillips: But just don’t kiss them during the pandemic.

Bringing a Collective Experience to Light: A Review of Melissa Febos's Girlhood

Melissa Febos opens her new essay collection, Girlhood, with a collage of visceral images of pain inflicted on the body—bloody knees, burned arms, skin rubbed raw. The opening essay is a lyric barrage of beautiful language and poetic image.

Melissa Febos opens her new essay collection, Girlhood, with a collage of visceral images of pain inflicted on the body—bloody knees, burned arms, skin rubbed raw. The opening essay is a lyric barrage of beautiful language and poetic image. In the essays that follow she looks back through a scrutinizing lens on her adolescence. Our very grown-up narrator takes us through the years she spent swimming in the ponds of Cape Cod, through most of her early sexual experiences, and into her late teens and twenties working as a Dominatrix in New York City. Using lyrical language and a meandering structure to move through her memories and experiences, the book also contains illustrations by Forsyth Harmon that highlight some of the most beautiful lines in the book.

Many of the places and scenes will be familiar for those who read her first book, Whip Smart, a memoir about being a dominatrix in New York City, and her essay collection, Abandon Me, about her father, her biological father, and a love affair gone wrong. But Ferbos’s voice and authority feel very different in this work. While the outside research and frequent metaphor were a large part of her second book Abandon Me—Girlhood moves from memoir to theory, and back again, with a new voice of authority.

Febos sets up the problem that she investigates in this collection, the conditioning of a patriarchal society, and really defines it for the reader in her opening Author’s Note:

“This training of our minds can lead to the exile of many parts of the self, to hatred and the abuse of our own bodies, the policing of other girls, and a lifetime of allegiance to values that do not prioritize our safety, happiness, freedom, or pleasure.”

I read this quote with intrigue, but did not feel this until I was well into her second essay, “Kettle Holes,” where our early-to-develop narrator is expelled from female social circles and sexualized and bullied by young boys. A rush of middle school memories returned to me. Friends whose names appeared on the bathroom stall with “slut” written over it in black sharpie markers, lying about periods and tampons and getting to third base, either because we wanted to give people the impression that we had, or because we wanted to give people the impression that we hadn’t.

She builds on this girlhood narrative in the third essay in the book, “The Mirror Test,” taking the reader on a graceful weave of early sexual exploration—safely on her own—and the harrowing experience of her external sexual experiences. Is it painful to read? At times, yes, but in the sense that she is bringing a collective girlhood experience to light, it feels freeing to see that pain and discomfort that is so rarely addressed put down on the page. Febos takes her time to explain that her experiences were not particularly unusual, she was not raped nor did she experience a specific isolated incident of trauma, but instead, she portrays through her narrative a system of patriarchy that young woman endure which is normal, everyday, and troubling.

My best friend and I, both straight white Midwestern women, spent much of our twenties attempting to unpack our early relationships and sexual experiences as newly college educated grown-ups. Why were we so insecure? Why didn’t we trust men to treat us well? Why did we fear other women—who might see us as a threat, who might be jealous or callous toward us? Where had all of this come from? This questioning and investigation is just the work Febos is doing in Girlhood. Our thoughtful narrator is pulling apart the threads of these early experiences and giving us a context for understanding them. Much of the book is woven narrative, careful to never leave us too long in those dark moments. She regularly moves into a mode of what I can only really explain as autotheory.

Arianne Zwartjes explains in her essay, “Autotheory as Rebellion” (Michigan Quarterly Review) how mixing theory with personal narrative has power: “In one way, autotheory is the chimera of research and imagination. It brings together autobiography with theory and a focus on situating oneself inside a larger world, and it melds these different ways of thinking in creative, unexpected ways.” While Febos is working her way through her girlhood experiences, she is also reaching out to other woman, seeking their stories. She pulls these characters into her own story and brings their voices to the page. She tells us about psychological research and anecdotal research and in doing so paints a much more layered experience than her story alone could accomplish. She doesn’t stop there. She also examines literature and movies to highlight the experiences we see and read about in the media—arguably forming our ideas and beliefs as much as our own experiences. (Her critique of the movie Easy A, a teen comedy from 2010, was easily my favorite.) This analysis from our patient, if not urgent, adult narrator is leading slowly toward her goal—an understanding of what happened to her and what it means.

In her Author’s Note, Febos explains another hurdle for the content of these essays—“For years, I considered it impossible to undo much of this indoctrination.” This struggle becomes more evident as the book progresses. The narrator becomes a young adult, who struggles with addiction and works as a dominatrix. She engages in relationships with women and men, some of them pretty dysfunctional. She does not give us easy answers, because she doesn’t have any. Her process of investigation, much like her other two books, makes her writing compulsively readable—we want to find out what she finds out. And in so many ways, for me, the reading experience is personal. Her lived experience as a young woman in America was too familiar. I didn’t have a stalker in my early twenties, but I knew other women who did. I didn’t feel forced to give a boy a hand-job when I was twelve, but I did for many years after. Even where her experiences were outside my own, they were achingly close to the darkest parts of the stories that shaped my understanding of sex and relationships growing up.

The adult Febos introduces us to her fiancé Donika, who acts as a bit of foil to our narrator. She questions the normalcy of the early experiences and pushes more investigation into her past. She offers an alternative way of looking at the “events” as Febos decides to call them, that live in her memories. The investigation seems to come to a head in the penultimate essay, “Thank You for Taking Care of Yourself” when Febos and Donika, along with a friend, go to a “cuddle party.” The seventy-six page essay traverses many topics, but the cuddle party drags us into the uncomfortable experience (at least for some) of physically being close to strangers—proof that Febos didn’t just mentally push herself to understand the lasting effect of her girlhood experiences, but physically tried to find situations that would help her undo them as well. As I read through some of the cringe-worthy experiences, I could help but think, Oh wow, my therapist would be proud of her! And perhaps this is part of the gift of this collection, she is doing a lot of emotional work, that many of us haven’t had the time or energy to do. It is the cuddle party that leads to Febos’s brilliant exposition on “empty consent”—a term that says so much. Febos explains:

“I see two powerful imperatives that collaborate to encourage empty consent: the need to protect our bodies from the violent retaliation of men and the need to protect the same men from the consequences of their own behavior, usually by assuming personal responsibility. It is our shame, our embarrassment, our duty alone to bear it.”

Giving a name to the expression of “yes” when what you really mean is: “I don’t know” or “I’m not sure” or “I want to say no but I don’t want to hurt your feelings or make you angry” was an especially powerful moment in her investigation.

Febos’s narratives continuously circle back to her youth. She raises the stories that dotted her girlhood over and over again. This continuous re-visiting mirrors our own memory, how they can pop up again and again, and allows her to reframe the narratives in new ways as she moves towards understanding. There are many moments that shine in Febos’s often lyric language and vivid imagery, but one that stuck out for me was in “The Mirror Test.” The narrator has gone to a liberal hippy summer camp, and she finds the camp director is a tattooed young woman, beautiful in overalls and a shaved head. She says of meeting her, “When she looked down at me, though I was terrified, I felt more seen than I’d ever felt under another person’s gaze.” Seeing an empowered woman through Febos’s eyes was a striking moment in her story. While Febos cannot literally go back in time to comfort her young self, she seems to have found a way to offer comfort, and a way forward, for her younger self, and for all the rest of us who lived through those troubling and isolating girlhood years.