To Shoehorn a Cat: A Conversation with Reese Conner

The dying or death of a cat allowed for a general exploration of grief, yes, but it also led to questions about what we are allowed to grieve, how much we are allowed to grieve, and who is allowed to grieve.

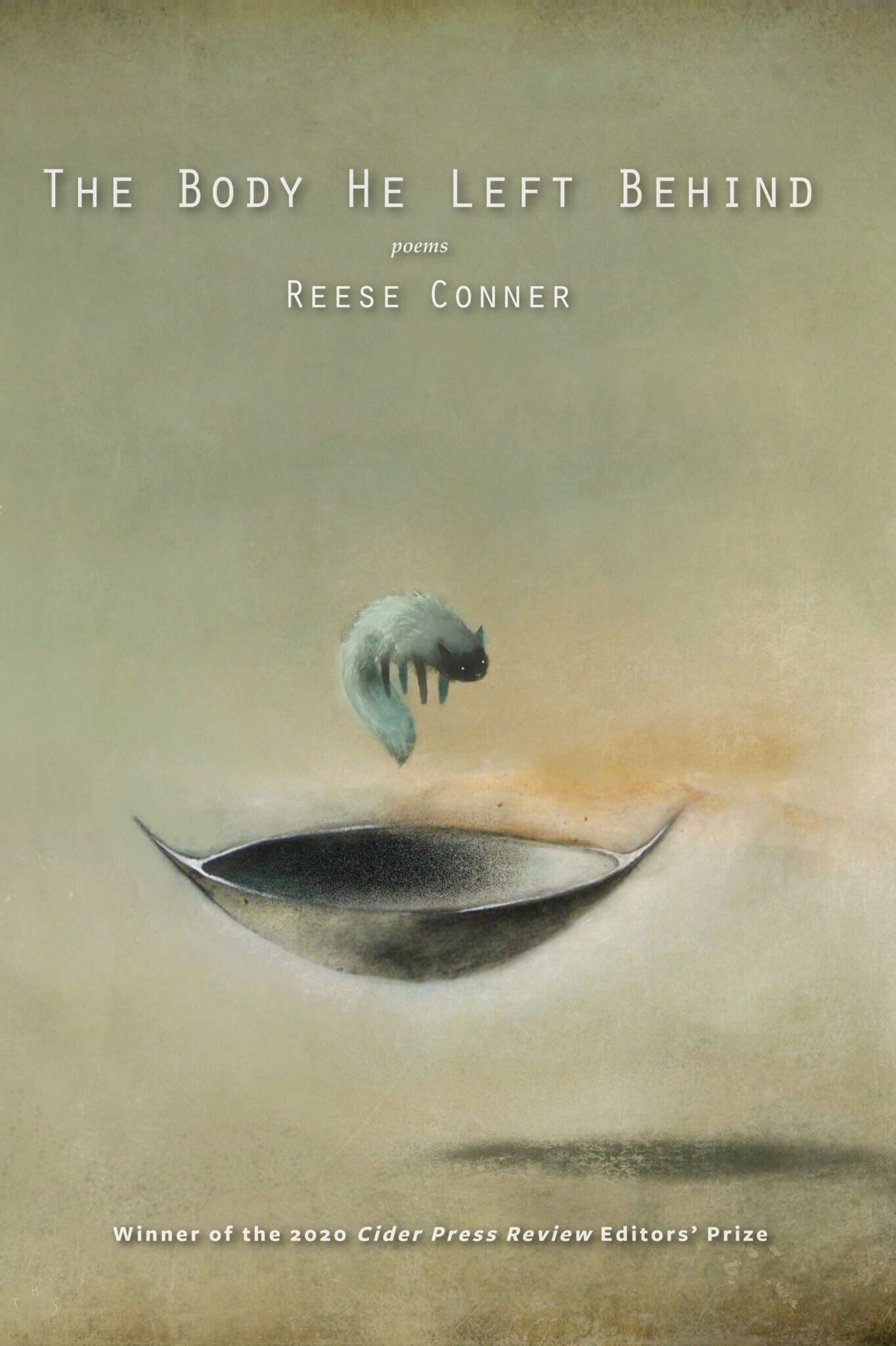

Reese Conner is a poet, teacher, and winner of the 2020 Cider Press Editors’ Prize Book Award for his debut poetry book, The Body He Left Behind. His work has appeared in Tin House, The Missouri Review, Ninth Letter, Barrelhouse, New Ohio Review, and elsewhere. His writing has received the Turner Prize from the Academy of American Poets and the Mabelle A. Lyon Poetry Award, and he has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Reese teaches composition and poetry workshops at Arizona State University.

I first met Reese in 2012 in Tempe, Arizona, where we were both incoming MFA Creative Writing students at Arizona State University. In the years since, I’ve been fortunate enough to have Reese, not only as a peer, but as a trivia teammate, Dungeons and Dragons comrade, and breakfast buddy. It has been a pleasure to see Reese grow as a poet in the time I’ve known him, to see his work become more biting, more introspective. I admire Reese’s ability to mix humor and earnestness, for his ability to look at what others want to turn away from. You can preorder The Body He Left Behind, a heartbreaking book of poems about cats, grief, and the ways we love, from Cider Press or your local bookstore.

*

Dana Diehl: We’ll start at the obvious place. What, for you, makes a cat such an enticing subject for a poem?

Reese Conner: Firstly, and I cannot stress this enough, I actually like cats. Let me tell you, actually liking cats did some hefty lifting when it came to writing a book chiefly about cats. The truth is I struggle mightily to simply start writing a poem, which I understand is a common issue for writers, so I don’t imagine myself unique. One way I found to combat that looming failure-to-launch was to shoehorn a cat into every piece I could because it created an immediate investment for me — I cared about the cat, so it made it easier for me to imagine the reader caring for the cat, too. That, in turn, made it easier for me to imagine the poem being successful and, therefore, worth writing.

Secondly, cats acted as vehicle to tackle some pretty big abstractions. For example, I was particularly interested in the ways we prepare for, encounter, and react to grief. The dying or death of a cat allowed for a general exploration of grief, yes, but it also led to questions about what we are allowed to grieve, how much we are allowed to grieve, and who is allowed to grieve. In one poem, “The Necessary,” I make this quite explicit by ranking griefs in order of importance. The point is not that an objective measurement of griefs coming from an external source is actually valuable, rather the point is that the ranking of griefs is a powerful, tacit thing that we already do. And that becomes wildly hurtful when one’s internal, subjective measurement of a grief does not align with where others think it ought to be. In particular, this comes into play with the father in the poems, who deeply loves his cat but does not feel comfortable mourning a cat on account of traditional masculinity. Come to think of it, exploring the effects of masculinity by way of a beloved cat is essentially the SparkNotes of my book. Even though I gave you the SparkNotes, I still hope you read it, though!

DD: I think there’s this fear that in writing about pets we risk being “cheesy” or overly sentimental. Is this something you actively tried to avoid while writing these poems? Or were there other challenges you felt you faced?

RC: Hmm…this is a really good question. I was certainly aware of the risk of sentimentality because I had been warned, but I guess I never really worried about it. In fact, I like to think that I purposefully approached the sentimental because, while it is often regarded as “cheesy” and lowbrow and not appropriate in a poem, there is a reason it is so ubiquitous, right? It speaks to shared experience. It must. We have Hallmark cards and abstractions because they resonate with just about everyone. And so, since the collective “we” has a penchant for getting overly sentimental about our pets, it seems pretty valuable to explore why. Pushing that further, it seems pretty valuable to explore why it is considered overly sentimental do so, especially if it is so common. Why is it that there is a perception that dead or dying pets should not be worth the grief we give them? I’ve certainly felt it — there is a guilt associated with mourning a pet so powerfully, and, in my experience, that guilt is a reaction to the idea that it is just a cat or just a dog, again referencing that unspoken hierarchy of griefs. In my book, I guess I wanted to legitimize mourning a pet so powerfully by exploring why the sentimentality makes sense and why we shouldn’t look down on it.

DD: Please tell us about the process of writing this collection. At what point did you know you had a book on your hands?

RC: I want to preface by making clear that I do not necessarily suggest the route I took because much of it was flailing about and generally having no idea about a great many things regarding publishing.

All right, so the one talent I know I have when it comes to writing is my ability to get lost in the weeds. I am consistently proud of my moment-to-moment choices within poems. You know, diction, line breaks, the particular idea I am trying to get at, etcetera? I’m proud of those. I really pay mind to have a rationale for each of those smaller choices in case the never-going-to-happen scenario of someone publicly holding me accountable for one such choice actually happens. This means that I am pretty confident in each poem I have written because I have the bandwidth to consider a full poem at a time. Unfortunately, that talent for the microscopic seems to have adversely affected my ability to see the big picture, which made organizing all my poems into a cohesive book quite the task.

And so, my process was mostly to lean into my talent and simply focus on each poem as a standalone. There was additional logic behind this approach because the idea of ever winning a book prize and publishing a book felt impossible, so it made sense to devote my attention to publishing individual poems. I didn’t really realize I had a book until I had enough poems to make a book. At that point, I took stock of what I was actually doing in my work as a whole.

All right, to be fair to myself, I may be being a bit misleading about how little I considered a book-length work. It’s not that I had never considered what my book might look like. For example, I knew, even as I was writing standalone poems, that fathers and cats and domesticity were through-lines for my work. I also knew exactly what the first and last poems in my book would be, and I knew the important poems that needed to go in-between in order to make the narrative work, but I had the vaguest idea of where those poems belonged. Essentially, I felt overwhelmed. When I had enough poems to meet book-prize criteria, I slapped together an iteration of my book that was significantly longer and less cohesive than what it is now. It also had a different title that I consider embarrassingly pretentious in hindsight: An Expectation of Broken Things.

Anyways, at this point, a wonderful friend and fellow writer, Melissa Goodrich, offered to slog through my mess and to help me out. I owe an incredible debt to her suggestions on ordering, cutting, and even the title of the book. Truly, I cannot overstate how integral Melissa’s involvement was in making my book what it is. You should absolutely check out her fiction and poetry because she’s not just an organizing maestro, she’s a damn good writer, too. When I read through my book as assembled by Melissa, I knew I had something to be proud of (and I knew I had someone to thank).

DD: In the first section of the book, there’s a focus on the physicality of the cat: old cat made of bird bone and balsa, broken rubber bands / heavy as ball bearings. However, as the book goes along, there’s a shift to the human body, as well. How are the body of the cat and the body of the boy connected for you?

RC: I guess those specific bodies are not terribly connected for me. Bodies, in general, were an important topic in the book, though. I wanted to really wrestle with the distinction (or lack thereof) between the body and the mind, which I know sounds like pseudo-philosophical bullshit, so we can roll our eyes together. Still, I recall a time when I was young where I honestly did not consider the two things as separate. That has changed. Now, when I define “me,” I am thinking of my mind primarily. And so, I am very interested in locating that last time when I hadn’t separated the two, when my body was “me” as much as anything else. Exploring that transition as well as exploring how we often define others as their bodies rather than their minds were important considerations when writing my book.

DD: This book takes a stark look at violence, as it is inflicted both by and on the subjects of these poems. The speaker loves his cats, while simultaneously observing their potential for brutality, their propensity to kill. The speaker begins to see violence in himself, as well.

I love this line from “I Was Innocent After All”: She told me / I had been good incorrectly […]

And this one, from “The Necessary”: To be clear, he is not a monster. / He simply decided that progress / meant putting things / where they do not belong […]

What do cats, or other animals, teach us about being a monster versus being innocent? Is it possible to be both at once?

RC: I think animals can teach us quite a bit about both monstrousness and innocence, particularly regarding the nuance of intentions mattering while concurrently not mattering at all. For example, in my poem “Like a Gift,” I address this head-on when the speaker is holding his cat to protect it from the neighbor’s dog. The cat recognizes the danger that the dog poses and would likely prefer to run away, so being arrested in the speaker’s arms probably doesn’t sit too well with the cat. And so, the poem posits that at some point the cat’s instinct to run from the dog becomes an instinct to run from the speaker, as well. This, in turn, poses the question of whether the speaker is correct to “save” the cat from its own instincts simply because the speaker has good intentions and the power to impose them. If the answer to that question seems simple and that the speaker was wholly in the right, then I would offer another set of questions regarding at what point the cat loses enough agency for the loss of agency to matter; at what point micromanaging the cat’s instinct becomes a trespass; and at what point the intention to save the cat from itself becomes monstrous. Obviously, I do not think there is an easy, blanket answer to these questions, which is why I do not offer one in the poem and why I won’t offer one here. What I do know is that many people seem to think good intentions earn a clear conscience, end stop. I believe that mindset can be incredibly dangerous and is often incredibly condescending, which is why it is something I address pretty heavily in my book.

DD: What are some other obsessions in your life right now? Do you find that they influence or inform your writing in any way?

RC: This is not a “right now” thing, but I have been obsessed with movies, television, and music for as long as I can remember. Each influences and informs my writing in powerful ways. In fact, I would say that my primary mode of experiencing stories is not through traditional reading but through those other modalities. I used to be pretty self-conscious about that because I felt like I couldn’t be a strong writer if reading traditional texts wasn’t my main source of reading. I do not think this is as widespread as it once was, but there is often an elitism when it comes to types of writing and, therefore, types of reading. I wholeheartedly disagree with it, but I’m sure you’ve heard this mantra: “Those who can’t write poetry, write short stories. Those who can’t write short stories, write novels. Those who can’t write novels, write screenplays.” I have heard that exact quote in multiple workshops throughout my career as a writer, and it always stung. I get it, though. Follow that proposed escalation in quality of writing and you essentially find the converse of who makes the most money from writing. Considering that, I can understand why some would want to believe in that hierarchy. After all, you’re not going to make much money from poetry, so it would be nice to believe that it is the purist expression of the lot. So, while I understand where the cliché comes from, I adamantly disagree with it and, more than that, think its utter bullshit. Good writing is good writing.

On a lighter note, I will offer one movie, television show, and song that helped inform some part of my book.

Movie: In Bruges.

Television show: Dollhouse.

Song: “Night Moves” by Bob Seger.

DD: If The Body He Left Behind had a soundtrack, what are a few songs that would be on that list?

RC: “Independence Day” by Bruce Springsteen. “As the World Caves In” by Matt Maltese. “Father and Son” by Yusuf / Cat Stevens. “Prison Trilogy (Billy Rose)” by Joan Baez. “Cat’s in the Cradle” by Harry Chapin. “Divorce Song” by Liz Phair.

DD: Finally, what advice do you have for emerging poets trying to finish or publish their first books?

RC: Well, I’m not sure if I have any advice on how to finish a first book other than to write it in a way that works for you and to take every bit of advice on how to write a book with just the biggest grain of salt. There are so many “truths” about what you need to do in order to be a writer and, while I think most of them are well-intentioned, they often serve to gatekeep who gets to be a “real” writer. As a wise interviewee once said: good writing is good writing.

As for publishing a first book, I do have some advice, and you may take it with whatever sized grain of salt you see fit: submit. Honestly, that’s it. I know so many ridiculously-talented writers who are too intimidated to submit, too afraid of rejection to submit, or who just don’t quite believe the mountain of failure that happens behind the scenes for just about every successful writer. If you are an emerging writer and you have conviction in your work, submit more than you think is necessary because that is what’s necessary. Get as comfortable as you can with rejection because, unfortunately, what you’ve heard is true: publishing is a numbers game.

Lastly, and this has nothing to do with finishing your own book or publishing your own book, but I’m going rouge with some unrelated advice: urge your own ridiculously-talented writer friends to submit, too. Be the good kind of envious when they succeed and support them as fully as they deserve.