Echoes of Duality: A Review of Brandon Rushton’s THE AIR IN THE AIR BEHIND IT

While Rushton gives name and shape to seemingly minuscule commonplace daily activities, one has to also be ready to navigate the unfamiliar contrasting territories that are somehow both beautiful and frightening.

Even the cover of Brandon Rushton’s, The Air in the Air Behind It, is an invitation to consider echoes and reverberations, the shadow lives that reside in one’s daily existence. Rushton’s lines and descriptions are at once equal parts familiar and surreal. In his proem, “Milankovitch Cycles,” the setting can simultaneously contain mundane routines like calling children in for dinner, set apart by an unlikely event such as “a meteor cuts through the low cloud-cover and all the stampeding herds abruptly stop…” While Rushton gives name and shape to seemingly minuscule commonplace daily activities, one has to also be ready to navigate the unfamiliar contrasting territories that are somehow both beautiful and frightening.

The landscapes within this work evoke stark contrasts and counterpoints for consideration. How can peaceful evening routines be tinged with dread, fear, melancholy, and doom? “Family members joined at a dinner table/bless the food, made/of chemicals bound to break their bodies/down.” Each poem begins with normalcy perhaps “kids kickstanding their bikes,” or a bus in a city “that smells and sounds just like a bus/in every other city.” There is a sense of comfort while navigating these scenes, however, these images and places quickly shapeshift to reveal poems that grapple with climate change, the end of the world, the role of the media, and how everyone’s very lives are held at the mercy of capitalistic goals and metrics. These end times feel closer than ever when visited in Rushton’s verses, well within the readers’ grasp of turning pages or the passing of another year.

Somehow Rushton likewise makes his readers certain that they aren’t the victims here and are complicit in the damages inflicted upon one another and the world. Rushton asserts “No one has enough/guts to do the good thing,” while lines later he goes on “It is so appropriately us, sizing up an abandoned/house from the street, deciding whether or not/to credit card the door lock and take a look around.” People can place blame and critique the actions of others all they want, but Rushton reminds them that no one is completely innocent in this lifetime.

Lest one think that Rushton’s work is one of indictment or preaching pithy lessons for how humans can live better, and do better; this book is a far cry from that summation. He masterfully culls together structured poems with three-line stanzas that ground, reorient, and release the tension. “The season smelled/like orchard work and you/in a dress time won’t allow me/to describe.” But he doesn’t leave anyone there for long and in fact, moves to “This place that hardly/now exists. I take a photograph/to memorialize the view. I shake it still./It is the shaking not the stillness/that persists.” Even in the calmest lines, Rushton continuously pulls the orderly rug out from under his reader, keeping them cascading into skinny short lined poems, or losing themselves in sprawling prose poems. They’re never quite sure whether they will return to a peaceful suburban town or one that makes them consider the collapse of the economy or fish washing up on a local shore. And in doing this, the reader is forced to embrace the beauty that can exist alongside the acceptance of their own eventual collapse and demise.

Rushton’s poems each connect to the next, line by line and page by page, filled with riddles of striking images to unpack and later revisit. This is a book that needs multiple readings to discover and digest all that Rushton shares. At first, a poem’s darker theme and tone stand out, but then subsequent readings reveal the work's lighter gauzy words and layers. Rushton is an expert of enjambment with dizzying turns of phrase and nuance that is concurrently succinct and poignant, yet feels effortless on the part of the poet. Whether he is exploring the dual meanings of phrases and couplings, like “puddle jumper,” or delving into the “private life is on the public train,” all will delight in savoring each one. His book is proof that when everything else is stripped away, stories are all that remain as “time/has trouble keeping up/it lengthens and then retracts.” “The wake splits behind/and then apart a lot like leaving.” The natural world and daily living are tenuous at best, but lucky enough for Rushton’s readers, The Air in the Air Behind It will be there to shepherd them through the chaos of the world.

An Ode to Lava, in the Voice of Lava: A Review of Katy Didden's ORE CHOIR, THE LAVA ON ICELAND

Layering source text, poetry, and photographic fragments of the Icelandic landscape, the images give testimony to the earth's predilection for breakage and change. Word and letter islands erupt as patterns over a landscape, only partially revealed.

Ore Choir sings an ode to Lava, in the voice of Lava. Yet, like Whitman's song these visual erasure poems belong to all creation. God-like in the power to destroy and create, Lava makes land that resembles the life of humans and their spiritual yearnings: "Here a soul found the origin / desire / under all things...." It is the soul and desire of rock that resounds, sung now and long after human life is gone from the planet. Lava shares our mortal fear: " I still blanche at the void. / The answer is, / again and again, / to erase the ground."

Layering source text, poetry, and photographic fragments of the Icelandic landscape, the images give testimony to the earth's predilection for breakage and change. Word and letter islands erupt as patterns over a landscape, only partially revealed. The volatile topography crinkles, heaves, and vanishes under the poems, the images resembling rodent-nibbled pages of an illuminated manuscript. Precise photographic detail defers to the sweep and gesture of graphic art, the texture often blurred by text, smoke, and steam, to nuanced effect.

The front cover shows a detail from the last image, speaking to nonlinear time. Words scatter or congeal to soften the impenetrable material of stone. This is work the book takes on—uncovering sentiment-free tenderness in what might appear to be only the violence of volcanoes and the hardness of rocks. " In love, / beyond these stones, / like water, / I rise." Land erased by lava, and lava, reimagine themselves, a phantasmagoria at once gleaming and terrifying: "Lava IS the dragon. / I clot the sky with gold."

A fainter pulse of the human in a dynamic universe suggests heavenly calm, glimpsed through the rain of lava and color washes of Iceland. Lava wields wisdom of geological and mystical realms: "I add land / and undo the maps. / Leaders stride / across trackless paths, / following the turning law back to the source." The poems flow with the internal logic of Lava as set forth in the book. Lyric time is deep time. Beginning at the center: "Art is central— / sun and stone. / I trace the beginning / of the modern; / I paint vales."

Thwarting the brain's expectation for saturated colors—specifically red and orange, the fiery reality of lava—the book offers photographs rendered in muted earth tones, (also gray blues and greens). Only occasionally does rock flush with the color of a drying wound. The poems mention the word 'red' only briefly. This strategy allows the reader to perceive Lava as pure force and being, rupturing and covering what exists in order to make it new. What is left unsaid, and what is omitted from the spectrum, the reader creates as afterimage. On the page, Lava throbs with white heat.

The Völva, the Priest, and the Scientist join the choir with questions. Answering the voice of the Scientist, Lava says: "I unmake eternity, / rewild gold, / fluent as the migratory birds / that reverse the ground." The Scientist asks: "What was fixed? What was fluid?" Lava's answer: "Lobes crept in hollows. Birds fled." These are questions we can ask about permanence and erasure, addressing the meaning of absence—the making and unmaking of a country, planet, or a self. When the priest asks Lava, after a great volcanic disaster and miracle: "How do I pray now?" Lava answers: "Nothing lasts. Bless that." This makes sense in deep time, and signals the inevitable return of earth to a place without humans. The questions arise: Is there light in this? Shall we mourn?

Ore formed, as a wish to: "know poetry..." and "... (ran) to put an end to war." War and poetry rear up like newly formed mountains in this chronicled metamorphosis. Geologically there are no surprises, because everything is a surprise. Capitalism gets its own succinct page—a blip in time, eternal consequence: "Capitalism co-opts ore, air, water, hour, epic." The elements join the ephemeral hour. Nothing is spared.

The final question of the book is the Scientist's: " What lingers? This invites us on a journey into the ore of possibility, and to seek human company in the face of climate change and suffering. In the voice of Lava: "Will you lean on each other / when I wreck the seasons?"

The relatively shallow space of the visual poems, despite streaks of distant vistas, creates an intimate space for the reader. This is, paradoxically, the perfect space for the eye-of- god vastness of the subject. At the edge of each image, a nomadic coastline is suggested, impossible to measure.

It is worth mentioning some of the compelling source texts that shimmer behind the upheavals, sometimes creating their own fire. They range from a Siggi's yogurt label to a Historical Dictionary of Iceland. A recipe for volcano bread makes a cheerful appearance. Benjamin Franklin, W. H. Auden, Jules Verne, and John Ashbery among others, speak from behind and formulate new meanings, interlaced with the lava fields. In this realm of restlessness, Lava is master.

Observant Eye: A Review of Stelios Mormoris’s THE OCULUS

The idea of a “compound eye” is very much a part of Mormoris’ vision. Joys and sorrows intertwine in this collection and Mormoris illuminates them with his observant eye.

The title of Stelios Mormoris’s The Oculus is based on his background in architecture and his fascination with the “round or oval opening, small rounded window, with or without a glass panel, which is generally located at the top of a dome.” His attention has long been drawn to examples of oculi in architecture, but he emphasizes that none of these has “more significance than the oculus of the eye.”

What the poet doesn’t mention is another definition of oculus, namely the botanical and zoological definition: “an eye, spec. the compound eye of an insect.” The idea of a “compound eye” is very much part of Mormoris’ vision.

The first poem, “Return of Icarus,” a persona prose poem, establishes the first lens of the oculus, the Icarus who didn’t just fail, but “set out” to fail, gifted “with wings of wax and feathers, every child’s sleeping and waking dream.” Rooted to the world with his “arsenal,” his choice was clear. He “flew straight into sky’s pandemonium,” listening to the sea below him and the sun above him.

This Icarus is drawn to the oculus of the high dome, but he sees with the oculus of the compound eye.

Icarus returns out of love and finds “the color of murder,” his lapsed friends, his cat, his father sleeping, each a visual detail, the cat “purring in a stand of reeds,” the father “sleeping with his hands on his face.”

Yet, there is a voice from above that wants Icarus to return, the voice that “was heaven’s blame in cloud-shredded rays.” Icarus, the I, is “back in the aegis,” he is “sheltered from sun,” and his home is “an eye a marrow of light, my oculus.”

Having established his perspective, the poet offers three sections of work: Sentries, Aureoles, and Verdicts. From a compound eye, Sentries explores facets of a love relationship, Aureoles views many places in the world, and Verdicts explores his relationship with and observations of his mother.

In Sentries, “Mimosa” begins with “You cut me,” immediately clarifying the depth of the relationship. The poet takes the reader through detailed images like “you were a bubble of air / rising in a water glass” and “you lifted my limp fingers / like unwatered stems,” to the point where the you,

took me by the hand into the garden

to stand before the greening lawn

as if it were a well

and said my name.

“The Fog” is past and present. “The fog becomes memory of fog…” and the “I” is “not exactly lost but in fear of being lost,” driving in the fog, holding “to the white neon dashes of the road.” There are images of descent, literal and figurative: “abysses everywhere that invited descent,” “shifted down for my safety,” and “lie down / at the nadir in a field of moss,” all of which rise to the final line, “I was in love.”

In the remaining poems of this section, many reference physical love, but all are detailed, imagistic, and linguistically original: “Poseidon’s spears spar,” “The insistent plea / that ‘love will end the madness’ / slithered inside me all day,” “the prized butterfly quivering // in a field of torn milkweed,” or the extended metaphor of trying to restore the “flung cup”,

white tips of light,

blue enamel lips of porcelain,

and the handle like a lost ear

falling forever.

In Aureoles, circles of light that surround something, especially as depicted in art around the head or body of a person represented as holy, the poet turns his eye on aureoles around the globe. He begins in Spain with “Corrida.” The poem snakes down the page as the poet recounts a bullfight interspersed with the observer’s comments, the “The false threat of the bull” that “looms like a cloud lowering,” the “silk’s scarlet red…catching my foreigner’s conscience / as a parody of blood and lapsed royalty,” the “dark maroon rivulets,” the cape slipping “to the ground like a dinner napkin.”

Whether in Paris, where tourists are “grazing on the excess grandeur of gargoyled boulevards,” or in San Francisco, where the poet remembers 1963 when he “straddled a pair of gleaming silver tracks,” waiting for a trolley, or in Oyster Bay, where the “tethered dinghy stirs, awakens, and makes a slow, circumspect circle like a clue,” each aureole has its own special time and place. In Kaiki Beach, he reminds us that even as there are circles of light, there is also darkness. The seafoam is like “torn lingerie,” and “a priest in a swath of black robe… gives his blessing to the unborn baby,” but this is followed immediately by “and, here, a coiled snake readies its strike in the tide’s aqua shallows.”

The third section, Verdicts, focuses on his mother. In this strong section, images of details sing and bring the mother to life. He begins with Barley, “barley crammed into thick honey laced with thyme.” Two thirds of the way through the poem,

she was dead

while we ate in the pew

together, children again,

and the reader, through the three word “she was dead,” is plunged with the poet into grief.

In “At Midnight,” the “mother’s thin hands” pull the plug on the Christmas tree lights which “froze into a filigreed silhouette of needles.” The poet waits for hunger to pass, for snow “to fall in the glass globe’s lens,” and to “bury my father / toppled like a log beside his dogs.” The juxtaposition of basic hunger, the small detail of the globe, and the enormity of burying a father heighten the large and the small.

In “The Apron,” the poet puts on his mother’s apron, shocked to find it

…hanging

on a nail, slump-shouldered,

as if she had just slipped out

in a rush to die.

So many details offer the reader a different perspective. In “Lord & Taylor,” the poet looks down to see “

…the delta of veins,

crepe skin over knuckles linked

like vertebrae, your wedding band gone…

then concludes “I knew you were broke.” This slant approach to the fact gives the fact potency.

Later in the section, he gives us his mother’s earlier years, first in “Margarita,” when the poet watches his mother put her “face on to face the morning,” then in “Mass in Harlem,” where he goes “straight to mass in Harlem,” where his mother was born. In “The Consommé,” he reminds the reader that

There will always

be spices in the spice

rack I can smell,

that refuse to perish,

reminding the reader that as long as he remembers her, blessed by the words “agapi mou,” she will have a form of eternity.

The poet dedicates his work to Margaret Zitis Mormoris with a quote from Kahlil Gibran: “We choose our joys and sorrows long before we experience them.”

Joys and sorrows intertwine in this collection and Mormoris illuminates them with his observant eye.

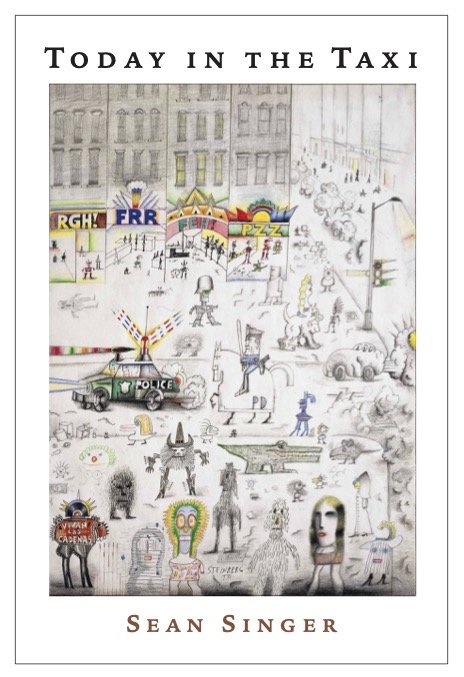

“I Was a Stranger, the One Who Could Remember”: A Review of Sean Singer’s TODAY IN THE TAXI

Singer leads us through an exploration of the taxi as a site of danger and intimacy, a place where feelings of unwanted desire or anger can push through at unexpected times. It is a unique venue, the driver and passengers are strangers thrust together in a space as private as any confessional booth.

New York City cab drivers have an almost mythic status in the American imagination. We think of them as loners who work the fringes of society, akin to cowboys in their savvy, self-reliant mode of living. Their occupation requires that they observe and listen to the needs of others while restraining their own impulses, so we ascribe to them the discerning, insightful minds of philosophers. In his latest collection, Today in the Taxi, Sean Singer elaborates on and complicates this mythic figure; he describes his own experiences as a cab driver, interweaving personal stories with thoughts on jazz music, Franz Kafka, the spiritual lives of prophets and saints, the films of Jim Jarmusch and his own wry sense of humor. In a voice that is both candid and lyrical by turns, Singer illuminates his experience as one of the urban workers whom Graham Russell Gao Hodges refers to as luftmenchen, meaning “people of wind, smoke and onion skin.”

Today in the Taxi is comprised of a series of sixty-two prose poems that take the form of diary entries. Each piece unfolds as a daily meditation on cab driving. In a poem whose title could be a deep cut from an obscure rock or jazz album, “Antivenom,” Singer begins by recounting the discomfort he felt when a passenger left her baby alone with him in his cab. He riffs off of this feeling of unease, jumping nimbly to thoughts of American saxophonist Don Byas and then to Franz Kafka. These discursions, like the arpeggiated improvisations of a jazz musician, sketch out a space of wonder and emotion; they allow us to follow the contours of Singer’s thoughts as he puzzles over the brief yet revealing interactions he has within the sacred precincts of the cab. I am reminded of Basho’s diaries-cum-haibun collections, Travelogue of Weather Beaten Bones, or Narrow Road to the Interior. Each of Basho’s diary entries begins with a recounting of daily experiences then shifts into the poetic reigster of haiku. Singer performs a similar gesture by relating the everyday events of his life, then drawing us into the symbolic, the interior of his being. “I use my breaking and steering inputs to turn inward,” he writes in the opening poem, “One Tenth.”

Through these hybrid poems we bear witness to Singer’s frustrations and the slights he is forced to suffer, issued by various occupants of his cab. “Sometimes passengers treat the driver like he’s invisible,” he laments, yet, in spite of this he maintains a generous spirit, interpreting his role as providential, part of a divine plan. When ferrying a man to meet his drug dealer he notes, “The vehicle is not just a way to get to the crime, but somehow to bless whatever the journey needs.” This thread of blessing and faith weaves throughout the collection, partly through Singer’s repeated references to a female-gendered entity called “the Lord.” This being, much like Singer himself, must perform the abject tasks of cleaning up and attending to things that others do not see. She must push a shopping cart full of plastic bottles taken from a trash can, she must swab the deck of the Orizaba, the steamship that Hart Crane leapt from to his death. In one poem she is a raccoon in Central Park North rooting through a garbage can. Who is she, this strange creature, part-terrestrial, part-divine, that transfigures herself repeatedly? Perhaps she is an aspect of Singer, himself, or perhaps she is a debased god, one that Singer can address without feeling pressured to prostrate himself.

Some of the strongest parts of the collection read like spiritual instructions issued by a cab driver. In “Limbo,” he writes:

When the oncoming headlights are too bright, it is said you should look to the side at the lines on the road. You would stop yourself from being blinded, and stop yourself to imagine the road ahead, unstrung, and the rubber against it.

In “Rites,” he explains “Driving it must be noted, is about 10% physical and 90% mental. The wheel obeys the commands of the rose brain and its taut rituals.” These observations convey the speaker’s identification with his role as cab driver. In the film Taxi Driver, Peter Boyle’s character says of cab driving: “A man takes a job and that job becomes what he is.” Singer expresses a similar sentiment in “Harlem River Drive,” “The driver is nothing without the 3,300 pounds of metal slicing the air,” he concludes. The speaker of these poems is not merely reporting his experiences, he embodies his vocation, he is one with his vehicle, the wheel, the tires and the road. This sense of oneness with his occupation invests the driver’s speech with a quality of transcendental vision. He transforms the act of cab driving into a spiritual discipline that runs parallel to the other forms of faith alluded to in the book.

Being a collection focused on the daily routines of a cab driver, the atmosphere of the metropolis pervades Today in the Taxi. Bare, gritty, skyscraper-lined New York streets wind across every page, as Singer leads us through an exploration of the taxi as a site of danger and intimacy, a place where feelings of unwanted desire or anger can push through at unexpected times. It is a unique venue, the driver and passengers are strangers thrust together in a space as private as any confessional booth. In Jim Jarmush’s nocturnal comedy-drama, Night on Earth, a film Singer cites in a poem bearing the same title, this is precisely the purpose the cab serves. To judge by Singer’s poems, this brief intimacy provides a window onto a wide array of human emotions and experiences. These collected vignettes create a dynamic mosaic of life in the city, one that is poignant, harrowing, and at times darkly funny.

Rather than existing purely as standalone pieces, these poems gain power through their connection to one another, in this way they are reminiscent of other poetry collections such as Dear Editor by Amy Newman, and, more recently, the hybrid collection, Dear Memory by Victoria Chang, both of which use the repeated epistolary form of address to yoke together a series of related poems or essays. The titular line “Today in the taxi…” not only establishes the diaristic mode of the poems, but also acts as a refrain, giving the whole book a larger music; it creates a rhythm that draws the reader from one poem to the next.

Throughout the book we experience a cab driver’s loneliness and abjection. Singer’s driver must bear the weight of human anger, sexuality, compulsion and fear. He must be the recorder of these events. “I was a stranger, the one who could remember,” he says, waiting in his cab for an ambulance to rescue an unconscious thirteen-year-old boy. Yet, these feelings never threaten to overwhelm the collection, instead we feel Singer’s reserve, his quiet watchfulness “I put up with things calmly, without weight, without bones…” Beyond the negotiation of these fraught interactions we sense a spiritual yearning. In the concluding poem of the collection, “Take Hold of It,” we recognize the job of cab driver as a spiritual path:

Tomorrow in the taxi it will be another day. I’ll read the book twice, then lend it out for someone else to read quickly, then I’ll read it again.

When a prophet asked the Lord about what the book meant, She said, Turn it and turn it again, for everything is in it…

Singer’s lord communicates her final thought to him, “Be silent, for this is the way I have determined it,” she says. The cab driver’s occupation, as rendered in this book, has been divinely ordained. The stories he recounts serve as metaphors for our lives, for the ways we must endure and accept each other with humility and patience, even as we exhaust one another with our frantic hunger to get from point A to point B. “Driving taught me to accept people for who they are, but other times I wish for an asteroid crashing into the city from the cold drain of space.” such is the cutting acceptance of reality that Today in the Taxi presents us with.

Taxi drivers, cast in the role of watchers and servants, are necessarily alone, their own lives hidden behind the role they play. It is hard to establish a genuine connection with people who come and go, who wash over the city streets like tides. Yet Singer’s cab driver never devolves into self-pity, instead, his thoughts go upwards, towards a personal spiritual force, or they pull downwards into the soul, the asphalt and the road itself. They gesture towards something human yet mythic, something that glitters with the city streetlights and wafts along on smog and steam into the realms of the mystic.

Rising and Falling on the Break: A Review of Lawrence Raab's APRIL AT THE RUINS

. . . the forest is a domain of experiences and of transformation and any physical limits we may experience are essentially meaningless except for its threshold. It is in the dark forest, the darkness inside us, where we must venture to find ourselves.

The poems in Lawrence Raab’s most recent collection, April at the Ruins, are a kind of plainsong, or plainchant. Like plainsong, the words, the lines on every page are characterized by a singular melody, to be sung without accompaniment. Each poem’s pulse is irregular, the rhythm free, not structured under more formal constraints. They are both of and outside of time, ancient and timeless, reaching us from far away in every direction in their monophonic resonance. The poems, in language stripped of its peculiarities, weave in and out of our lives, connecting the stories and myths that tether us to emergent truths we are unable to escape, and confirm our failings of imagination the harder we try. Raab knows there are no new stories to be told, just new ways of experiencing how we know them. The poems in this collection are uncluttered by repeating refrains and unwavering in their singular devotion to acknowledge the darkness and (un)/cover our unrelenting presence in it.

Forests appear in countless works of literature. The forest is a topos, whose physical boundaries carry less literary value. Meaning, the forest is a domain of experiences and of transformation and any physical limits we may experience are essentially meaningless except for its threshold. It is in the dark forest, the darkness inside us, where we must venture to find ourselves: it is the belly of the whale; a cave of shadows. In the cedar forest, Gilgamesh defeats Humbaba in pursuit of immortality. In Little Red Riding Hood, a girl and her grandmother are swallowed whole by a wolf before being saved by the huntsman. In Raab’s “After the Sky Had Fallen” we are thrust to the forest’s threshold, just moments after Foxy Loxy (or Fox-Lox, or Raev Skraev) has lured everyone into his cave beyond the forest’s edge and devoured them, “After which the thatch / of night surrounds [us] / the lost children.” It is impossible to ignore the number of ways we encounter the trees throughout the book. Enough that we wonder at the poet’s truest reasons.

It is not just the edge of forests that the reader must concern themselves with. In “A Little Music” (dedicated to the poet Stephen Dunn) we find the speaker restless at the edge of the poetic moment, ready to be transformed, where “…all the poems / about death had been written,” and where “…all the poems of the future / had exhausted us.” The speaker realizes the transformative moment they are seeking remains unchanged whether it reaches them from “an ancient city” or is “mixing / with the murmur of the sea.” The poem is always reaching them from a recent moment in time other than this one, as a song, as “a little music [arriving] from far away.” And what they assumed was theirs to give, a gift, a chance to give their reader one more opportunity “to walk out into a meadow / of improbable beauty” was never, in fact, theirs, and has always been becoming theirs—not a thing they can impart or teach, but a thing which they have always been confirming by virtue of attempting to give it away. The thresholds are strikingly familiar, and we must wonder then what’s left of wonder, if its unattainable position at the horizon of our understanding is meant to forever elude us.

Raab further threads pasts into presents in the title poem, “April at the Ruins,” a nod to a poem by the same name by H.R. Kent (and to Kent’s nod to Wordsworth) in which we are once again (re)visited by “a little music which arrives from far away.” In Kent’s poem by the same name, we are “…pilgrims / hauling our restlessness through the marigolds,” in awe of nature’s emergence, extoling the flowers. By the time the poem reaches us through Raab’s singular melody, we are relieved of Kent’s “nostalgia / for this place . . . as we walk away from earth,” April truly at the ruins, seemingly lamenting its own annual re-emergence:

In the early morning, frost catches

hold of the new buds that dared

to open. Now, thinks the tree,

I’m going to have to do this all over,

but the leaves will be smaller,

and more vulnerable

Each of us/in each of us is an April at the ruins, never released from all manners of emergence(y), though we are expected to mistake it for anew every time.

At last, in “Stopping by Woods,” we find Raab in conversation with the ghost of Frost, “not far from those trees / that seem to be hiding something.” Here, the speaker acknowledges the trees, the moment, the as of yet experienced transformative experience like a God watching their creation discover what they’ve known will be discovered by their creation all along. But what does it matter either way? The speaker acknowledges the division between what we feel ought to be happening and whether anything ought to happen at all, shattering the illusion about a poem’s purpose, about a poem’s position as transformative experience, as forest. “But this is a poem,” the speaker says, “not life, where nothing / has to add up,” and why we find ourselves expecting we’ll “be given / at the end some useful idea / about duty or time.” And, despite his obvious objections, the irony is we are, and that is the mastery of Raab’s poetry, and of this collection, where we are “watching the snow, lovely / as it is, falling, / and continuing to fall,” and will always be falling if we ask it to.

April at the Ruins by Lawrence Raab is a Neo-Romantic excursion, replete with forests, dark shadows, and ancient echoings. However, the literary ruins we revisit throughout speak of unchanging realms within us we must encounter even if darkness is the outcome and even if the artifice of the “poetic moment” can no longer transform. We are once and for all, with each plainchant, sung without accompaniment, relieved the burden of transposing wonder onto the world. And we are better armed for the task for having spent time here, each poem singular in voice, irregular and free, rising and falling on the break of the line.

Looking Up and Other Dangers: A Review of Corey Van Landingham's LOVE LETTER TO WHO OWNS THE HEAVENS

In her stunning second poetry collection, Corey Van Landingham asks us to look and look again at the cyclical tragedy of war.

In her stunning second poetry collection, Love Letter to Who Owns the Heavens, Corey Van Landingham asks us to look and look again at the cyclical tragedy of war. Her richly layered and intricate poems use modern settings and relationships as stages for pageantries of desire and dominance, encounter and estrangement. In them, she reflects on the disconnect people experience when they view others, objects, and events from a distance. Much like the remove many may feel in regard to the drone, the primary subject of the book.

Throughout the collection, Van Landingham chooses a lens of exposure and exhibition, both of her speakers and the others they encounter in the poems. Rather than launch a removed observational critique, Van Landingham seems to situate herself within the mess. She introduces herself in relation to the drone (“In the Year of No Sleep”):

Long nights I would… watch the simulated

stock ticker make senseless

money for people I will never

see. Across the country men

make invisible machines…

The stock market’s steadiness, its business as usual, is contrasted with the abrupt destruction of a targeted drone attack. It happens, life goes on. Later a similar contrast is made in “Recessional," where Van Landingham describes a wedding in detail:

and not one of us thinks what we look like

from above, nor of

the eleven-vehicle wedding procession

delivering the newlyweds

to the groom’s remote village…

One man looks up.

We know the rest from headlines.

And it costs us nothing, Van Landingham seems to say. Too easy. Too easy to put away from sight and memory. It happens. Even when we know about it, we move on.

I think the brilliance of these poems is they offer different lenses for us to look through— to keep exploring and perhaps better understand the human impulses behind desire and destruction. It’s interesting to note that most characters in the poems are innocent bystanders, observers of art, at a distance from war—a daughter of her deceased father (“Elegy”), a teacher of her students (“In the Year of No Sleep”), young girls of the mysterious antics of unruly boys (“Field Trip," “The Goodly Creatures of Shady Grove”). In “Love Letter to the President,” we learn the senate has “quietly stripped a provision to an intelligence bill” which would have required the president to make public the number of people killed or injured. The speaker’s outrage takes a darkly humorous turn, offering an I’ll show you mine if you show me yours—the number of boys she made out with as a teenager for the number of people the government injured or killed.

The poems are often ekphrastic, directly responding to masterpieces about war. In “Love Letter to Nike Alighting on a Warship,” the drone is likened to a famous statue (Winged Victory of Samothrace)—“ears stripped, mouthless—Good Girl! Broken Goddess!”; Van Landingham quotes Dickinson equating sleeping with “ignorance and error”; relates how at night the drones must still land on the ground. They almost seem animal, like they need rest too. And men use their hands to clean their wings. There’s more complicity in this recognition, some of the distance removed. Though their destruction is remote, the drones still need care. Human hands must still perform their maintenance and operation: “Stand back, a docent / warned me then. You’re getting, he said, too close to her.” There’s distance and yet proximity again, this time alluding to the speaker’s closeness to the statue, and also to something truer and deeper than history’s celebratory tales of dominance and defeat.

Van Landingham seems to be exploring the space between us—our potential for creation as well as destruction. In every poem, beauty is juxtaposed alongside cruelty. In “The Goodly Creatures of Shady Grove,” Van Landingham references Miranda in The Tempest in order to highlight humanity’s potential for naïveté, as well as our own responsibility to see what’s in front of us. Young girls watch the spectacle of boys jumping off a bridge: “In the self-same space as wanting, cruelty is born”—one boy catches a fish with his shirt and then beats it against concrete: “He wants the other boys / to see the girls see what his hands can do.” Even children are capable of cruelty and can recognize when something is kind or not. Even children may be swayed by the desire to be desired. Misguided in so many ways.

How do we navigate this space between us when it holds such potential for love and destruction? Many poems explore the dynamics of a couple or perhaps couples, layered with references to historical divides: an ill-fated pair encounter history and natural boundaries on a road trip in the “Great Continental Divide;” a long-distance lover reflects on differences in weather between the two coasts and the seeming impermanence of love (“On a Morning Where Our Weather is 60 Degrees Different”). The author seems to be saying that there are natural distances that happen between man—our coming together, our moving apart. And there are ways to bridge that divide, means of connection. In “Transcontinental Telephone Line,” a long distance couple use phones to bridge the distance, yet:

Eleven days after the line was finally

finished, Franz and Sophie were shot in Serbia

and the world was dark for four more years.

Technology brings light yet also ushers in darkness. Are we better for being able to talk across miles, where our words are no longer private? To be located by satellite where a drone can snuff out human life at any instant?

“Elegy for the Sext” contrasts a personal moment of sexting with other historical moments—the first image from a comet, the Berlin Wall broken down, how one can own a graffitied piece of the wall: “It is true that, once the body becomes fixed, it is too much itself.” She seems to be speaking to the human drive to capture, possess, and objectify moments in time—whether an intimate picture of a body, a (literally) concrete piece of history, or a photo of something we would never normally see, if not for technology: “Once the body becomes a downloadable thing, is it true?” Are we better for seeing, knowing, capturing these images, or lessened? This poem leads us into a series of poems written in response to an art exhibit depicting scenes from the Civil War.

In “Cyclorama,” Van Landingham plays with line length and page formatting to describe her own and other visitors’ perspectives and responses to the Gettysburg Cyclorama: “We, astonished readers of history, lean forward. But / the thick railing holds us back. Denies the moment.”

Art is a way into the past, yet still, we find ourselves held back from war’s reality in so many ways. The line between entertainment, ideology and education is so easily blurred. Visitors’s words make for some poignant moments:

I never could have

done it, march across, like, a wide-open field…

No, that one’s Little Round Top.

Where we ate our lunch.

The author then interjects surprising insight into the human condition:

The sold-out

showings prove this—in Atlanta and Pyongyang,

in the Kunstmuseum Thun and Berlin, Ohio—

how we have in us a taste for beauty and for

terror.

In “Love Letter to MQ-1C Gray Eagle,” the speaker addresses the drone by name, alludes to a deeper knowing of this new form of warfare. She describes being seen doing simple innocent things like picking a fig from a tree and eating it, like “lovers / consume things, in the moment, making the flies jealous,” comparing how quick and complete the drone destroys people. “We could get on like this, at a distance,” she says, alluding to her former poems about long-distance lovers, the ways technology allows the lovers to see and be intimate with each other: "I could pretend / to see you. I could flash you my mediocre breasts.” Again, the theme of exhibition and shame—she confesses feeding moths to her cats and then crying after: “I’m often / sorry about what I do, even if I don’t stop my actions.”

The author understands here that we all fall short of our better intentions. We can recognize our actions as wrong and still not stop. The last line of the poem is particularly striking:

If you require no hands and I require no

privacy, aren’t we destined to be less human together in the dark?

Van Landingham raises so many questions in her poems, none of which have neat or simple answers. Perhaps in the looking and looking again, in the reflecting and bringing these matters to light, we might still reclaim what slowly and surely is being lost.

An Element of Blank: Cynie Cory Reviews TENSION : RUPTURE by Cutter Streeby and Michael Haight

This mindscape is precisely where memory and self (identity) are interrogated. The subject of the Tension : Rupture is this performance.

Tension : Rupture is a hybrid collaboration of poems and paintings by Cutter Streeby and Michael Haight whose borders dissolve into liminalities. The performance is often hypnotic and dreamlike, an Aurora Borealis whose shapes and colors shift across the page. Tension : Rupture asks the reader to participate in the interstitial spaces where the drama of the poem/paintings unfold. Here, the reader becomes the third collaborator as she deep dives into the re/construction of history. This mindscape is precisely where memory and self (identity) are interrogated. The triumph of Tension : Rupture is also its subject: performance.

As a title, Tension : Rupture, behaves as a poem within a poem, in the sense that it both reveals and mirrors the collection’s form and content; specifically, its dramatic unfolding and ambiguity. Its architectonics create an impending action. If we look more closely, we see a gathering of moments between the action of undoing and the undoing itself. (Think pin pulled from a grenade.) The juxtaposition of its discordant words is set to discharge. It is the space around the colon that charges the moment. The colon is the force that propels a thought or word forward. “Tension” is disrupted by white space which halts the action that the colon creates. Time elasticates. This is a profound moment of violence. The title further subverts our expectations by creating the action of holding together that which is falling apart.

When Hamlet is poised to say his soliloquy(s) the audience is compelled to listen because we sense that 1) he will reveal a point of action that will further the plot and/or 2) that he will reveal himself. Shakespeare complicates this dramatic structure by inviting the audience to eavesdrop (participate) on Hamlet’s soliloquy(s) thereby creating the unexpected interlocutor. We are compelled to listen to the Dane’s inner workings because they are both inner and workings. This is similarly so in the Streeby/Haight book where private also meets public. Hamlet’s words reveal, in real time, the intimate action of self-interrogation as does the interface of Streeby and Haight’s collision.

The shared liminalities reveal both the violence of the collision of text and self/alterity and in exploring/excavating this history. We may think of this book as a poetics of trauma as we may also see Hamlet as a play of trauma. Yet in Hamlet, one may argue, there is no redemption. Here, in this intertextual world of unmerciful searching for identity, one has the sense that Streeby wishes he could circumvent words altogether – one feels and sees the pressure placed on meaning – because words do not “say to say”: they do not and cannot alone tell the truth. In their tireless pursuit of truth telling, Streeby and Haight use the page not so much as canvas but as twilight, where the gaps between light and dark and between memory and imagination are places of ruin and revelation.