Lydia Millet On Karel Capek’s War With the Newts

I first encountered the bulgy-eyed protagonists of Karel Capek’s monumentally great — poignant! and hilarious! — 1937 novel War With the Newts when I was in my early 20s, living in L.A. and working as a peon copy editor at Hustler Magazine.

I first encountered the bulgy-eyed protagonists of Karel Capek’s monumentally great — poignant! and hilarious! — 1937 novel War With the Newts when I was in my early 20s, living in L.A. and working as a peon copy editor at Hustler Magazine. Andrias Scheuchzeri, a species of newt first discovered (according to the book) by a ship captain in the waters off a remote island near Sumatra, was a salamander capable of walking upright — as well as synthesizing information and acquiring human language. His creator, Czech writer Karel Capek, is best known as the man who made up the word robot. A brilliant humorist and allegorist, Capek was also a journalist in post-World War I Prague, a contemporary of the more inwardly turned Franz Kafka, and one of the most imaginative early writers of science fiction. He was a pragmatic and actively political writer. “Literature that does not care about reality or about what is really happening to the world,” he wrote, “literature that is reluctant to react as strongly as word and thought allow, is not for me.” War With the Newts was his last novel; the best English translation is by M. and R. Weatherall, published in 1937.

Capek’s newts are naïve, childlike specimens when first encountered in the wild and put to work diving for pearls by the greedy, paternalistic Captain van Toch. Standing about the height of a “ten-year-old boy,” the newts have hands, tails, and a habit of smacking their lips; when they first meet humans they stand up on their hind legs in shallow water, wriggle, and emit a clicking, hissing bark that sounds like ts, ts. Pitifully eager to please, they’re subjugated, tortured and often massacred with impunity; their trusting natures make them the perfect victims.

Packed into filthy cargo ships to die of starvation or infection, bred for servitude, sent off to zoos and work farms and animal research labs, the newts gradually learn to distrust. But before they rebel, many are assimilated into human culture. With innocent admiration for the accomplishments of their human captors, they adopt bourgeois manners and customs; study etiquette; and enroll in universities, sometimes becoming respected scholars who — because they live mostly in water — have to deliver their lectures from bathtubs. Young female newts, who attend a finishing school wearing modest makeshift skirts donated by decency-loving matrons, come to worship their do-gooder headmistress as a saint. And one tourist couple vacationing in the Galápagos encounters an earnest and studious newt who goes nowhere without his well-thumbed copy of Czech for Newts, a phrasebook he has memorized. “This booklet . . . has become my dearest companion,” the newt tells the Czech couple, and proceeds to grill them on the details of Czech history. “I should like to stand myself on the sacred spot where the Czech noblemen were executed, as well as on the other famous places of cruel injustice.”

When the pearls the newts have customarily harvested for their masters become scarce, the newts themselves become the world’s most important commodity, traded by the tens of millions on the stock exchange. Different categories of newts fetch different prices: there are Leading, Heavy, Team, Odd Jobs, Trash and Spawn newts, with the Leading being intelligent, trained leaders of labor columns and the Trash being “inferior, weak, or physically defective newts.” farms all along the coastlines of the world produce newts by the hundreds of millions — until finally the newts’ undersea civilization expands and industrializes so extensively that newts far outnumber and outgun their human counterparts. Unfortunately for the human race, newts require coastlines: only there, in the shallow water, can they live. As their population explodes, they run out of coast.

And so the “earthquakes” begin. Cataclysmic seismic activity across coastal Gulf states from Texas to Alabama are referred to as “the Earthquake in Louisiana” and soon followed by earthquakes in China and Africa. Finally European radio stations pick up a croaking voice, and Chief Salamander begins to speak: “Your explosives have done well. We thank you. Hello, you people!” He explains that the newts have run out of room and now will be forced to break down the continents to create more living space. Indifferent to human welfare, the newt civilization is driven by a mindless urge to expand.

The genius of War With the Newts lies less in its plot or its wry political wisdom than in its exceptional newt portraiture. These talking salamanders are at least half human; their anthropomorphic charm makes them unforgettable. Exaggerations of pragmatic, economic modern man, they’re as devoid of passion as they are of morality. Newts is an extraordinary novel in its humor and its casual devastation, making old-fashioned religious apocalypses look romantic, wistful, and even optimistic when compared with the soulless apocalypses we’ve come to know lately, where mass murder is an arithmetic performed in the name of, say, cheap gas for our cars or the convenience of our lifestyle. Capek’s newts are a product of European literary culture, but in many respects they look a lot like Americans.

“The mountains will be pulled down last,” says Chief Salamander. “Hello, you men. Now we shall send out light music from your gramophones.”

*

Editor’s Note: “Lydia Millet On Karel Capek’s War With the Newts” is adapted from a piece written for Remarkable Reads: 34 Writers and Their Adventures in Reading, edited by J. Peder Zane (Norton, 2004).

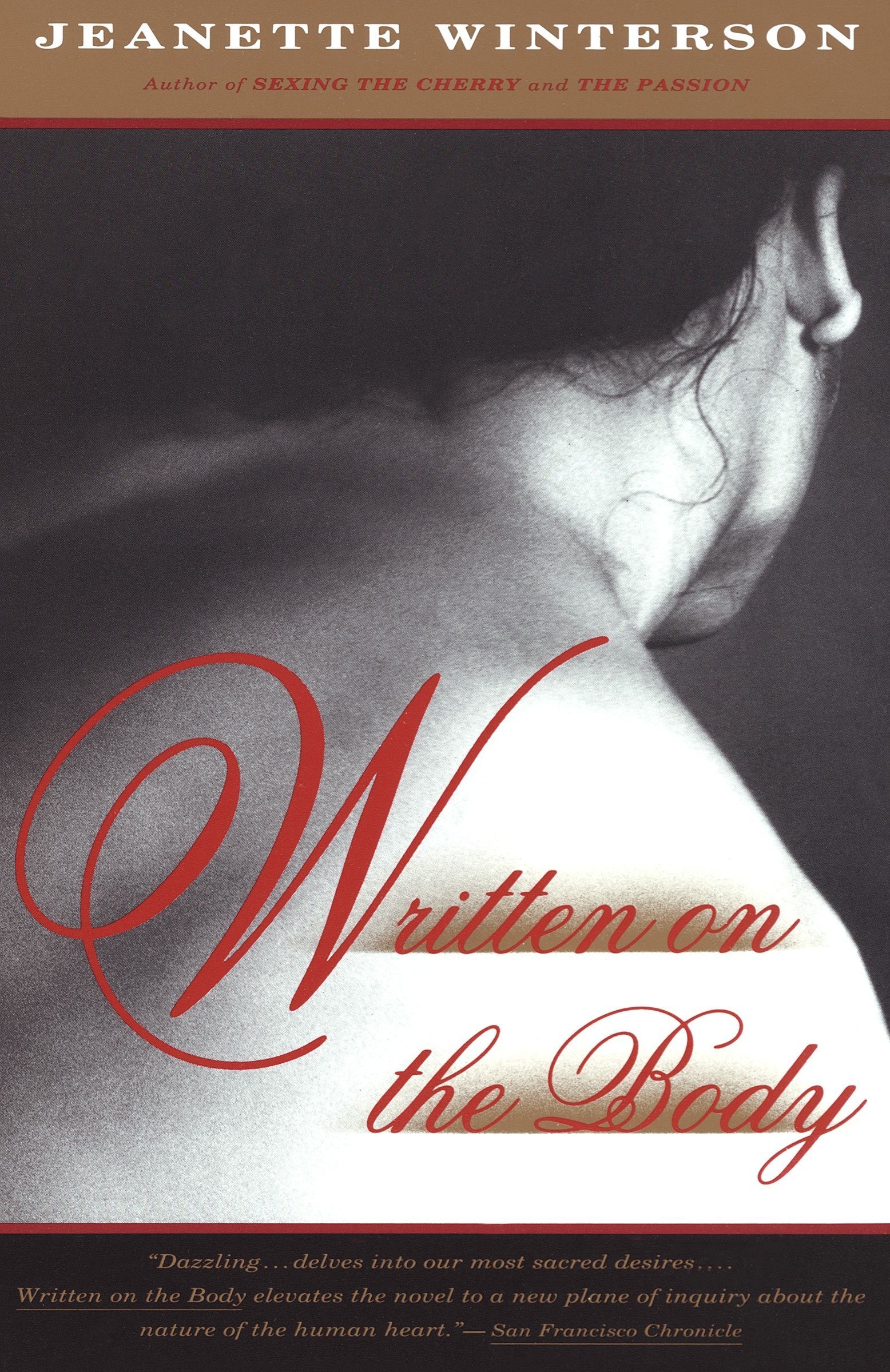

On the Surface, Written On the Body Is a Love Story for the Repentant Commitmentphobe; For Me, It Is a Shelter from Adolescent Heartache

It is by no means a perfect book. While it may be cathartic to project all of our hatred onto the narrator, having an unlikeable narrator makes for a frustrating reading experience. To Winterson’s credit, the narrator’s ambiguous identity allows us to hold a mirror up to not only the person we want to hate, but to ourselves, our flaws. Our discomfort with this narrator is part dredged-up memory and part recognition of something we don’t like about who we are or how we act.

I first read Jeanette Winterson in college, for a course on the philosophy of art. We were assigned to read several essays from Art Objects: Essays on Ecstasy and Effrontery. The title essay has stuck with me in the years since that course mostly because it offered the most understandable foundation for a class I typically felt lost in, but also because reading Jeanette Winterson felt like slipping into something eccentric and luxurious. Her storytelling style in this essay is straightforward, nearly confrontational for those who do not care about engaging in art. Simply put, art is a full-contact sport.

It turns out, love is too. I was 19 — hurt and confused by a spectacularly failed romance — when I bought Written on the Body. On the surface, it is a love story for the repentant commitmentphobe; for me, it is a shelter from adolescent heartache. An initially unsympathetic narrator gives us someone to hate, someone who is not the person we loved until we couldn’t. Watching the narrator reform gives us hope that people have the capacity to change.

It is by no means a perfect book. While it may be cathartic to project all of our hatred onto the narrator, having an unlikeable narrator makes for a frustrating reading experience. To Winterson’s credit, the narrator’s ambiguous identity allows us to hold a mirror up to not only the person we want to hate, but to ourselves, our flaws. Our discomfort with this narrator is part dredged-up memory and part recognition of something we don’t like about who we are or how we act.

A brief summary: Our nameless and genderless narrator has a history of abandoning relationships once the novelty wears off. Along comes Louise, vivacious and sexy and . . . married. To a man. Who works long hours, leaving his wife home alone most of the week. With the house to themselves, Louise and the narrator have their fair share of romps, narrowly avoiding being caught by Louise’s husband. Shortly after leaving him, Louise finds out she has cancer and she leaves the narrator as well.

To cope with Louise’s departure, the narrator moves into a tiny cottage and devotes every waking hour to the medical reference section of the local library:

“If I could not put Louise out of my mind I would drown myself in her. Within the clinical language, through the dispassionate view of the sucking, sweating, greedy, defecating self, I found a love-poem to Louise. I would go on knowing her, more intimately than the skin, hair and voice that I craved. I would recognise her plasma, her spleen, her synovial fluid. I would recognise her even when her body had long since fallen away.”

Thus concludes the first part of the book. The second part, the reward for making it through the sometimes uncomfortable, unenjoyable first, is the catalog of the narrator’s newly acquired knowledge of human anatomy married with memories of Louise’s now failing body. Winterson plays with the concept of what it means to know a person inside and out, something we typically consider synonymous with intimacy. The second half of the book is divided into five sections, the first four of which relate to the hours dedicated to anatomical study; the last section is a return to the more straightforward narrative of the first half. Each of the four anatomical sections — one each for the cells, the skin, the skeleton, and the special senses — is written in a stream of consciousness that is at once tender and epic, occasionally dipping into the Bible and other mythologies. From any other writer, this approach might seem hyperbolic, but Winterson is able to make it urgently loving (and maybe a little bit sexy).

Here, the narrator literally learns about Louise, and every other previous lover, from the inside out. It’s the only possible way to compensate and / or atone for being, frankly, a shitty partner. Only through these self-imposed anatomy lessons does the narrator learn how to properly love Louise for everything she is.

Winterson’s style in the second half of Written on the Body is such a departure from the take-no-crap criticism that knocked my socks off in philosophy class. Instead, I was greeted with unanticipated tenderness, particularly in the latter half of the book. I was prepared to hate the narrator as much as I hated the boy who wronged me during winter break; but as the narrator’s steeliness was worn down during the exploration of Louise — her body, her disease, her mythology — I found myself coming around to the boy. I saw him as a human, deeply flawed and hurting from problems of his own.

I still have mixed feelings about this experience — was I in fact the frosty unlikable narrator who needed to learn how to love without putting up insurmountable walls? — but I am thankful for having lived through it. I am reminded of a concept introduced in Art Objects, Winterson’s theory that our negative responses to art have more to do with us and our lack of understanding than with the art itself. My recoiling from the narrator of Written on the Body is a mirror showing me something I didn’t like about myself. The narrator’s capacity to learn, appreciate, forgive, showed that I have the capacity to do the same and that the boy has the capacity to heal.

The narrator may not have been able to fully love Louise. I may not have been able to fully love this boy, nor he could he fully love me. But I can say that I am able to fully love myself, flaws and all.

How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive Is An Essential Manual for the Romanticist In Everyone

Written with brilliant wit and a sensitive touch, How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alivemimics the style of John Muir’s 1969 manual of nearly the same name, slipping in and out of surrealist car maintenance passages while telling the story of Boucher’s son, his ’71 VW, as they both process the death of Boucher’s father at the hands of the Heart Attack Tree.

Remember that old red pickup truck you had when you were in high school? The one with the bench seat that was so narrow the middle seater had to straddle the stick shift while you awkwardly rested your arm on their leg when shifting gears? You loved that car, even kept it filled with gas and fresh washing fluid sometimes. Then one afternoon when you were rolling over the last speedbump in the afterschool exodus line the engine fell out, splintered on the cement. You sat for a few moments behind the wheel while the impatient honked behind you, remembering the time you sat in the drive-in theater and kissed that girl until the movie’s soundtrack turned to static. You haven’t seen it in years, but now here it is and damn did you love that automobile.

Christopher Boucher knows how you feel; he’s been there with his ’71 Volkswagen too, broken down in the middle of 91 just outside Northampton, Massachusetts. His bleeding manual How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive instructs on more than how to find the beating engineheart of your VW: it also teaches about the anger, regret, and love that motivate us after the death of a parent.

Written with brilliant wit and a sensitive touch, How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alivemimics the style of John Muir’s 1969 manual of nearly the same name, slipping in and out of surrealist car maintenance passages while telling the story of Boucher’s son, his ’71 VW, as they both process the death of Boucher’s father at the hands of the Heart Attack Tree.

I know it sounds like a bizarre premise (it is) and it can be confusing when Boucher guts the definition of words, but the story, and new words, are injected with a glowing, wistful emotion that turn piñatas into evenings filled with small moments of time and girlfriends into women made of stained glass that shatter if they get too cold and are impossible to resist.

Simply, How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive is an essential manual for the romanticist in everyone.

A Portrait of a (Would-Be) Jersey Artist Reading A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

I was a sophomore in college when I read A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man all the way to the last line for the first time. I was about the same age as Joyce’s hero Stephen Dedalus, though not nearly so well educated. I had working-class New Jersey to thank for that. Joyce’s Stephen had his narrow Ireland, “the old sow that eats her farrow,” as Dedalus describes the country of his birth in his monumental colloquy with his friend Cranly in the penultimate section of the novel — Ireland with its strident priests, dour schoolmasters, inebriated fathers, and demanding God. But also with its classical curriculum.

I was a sophomore in college when I read A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man all the way to the last line for the first time. I was about the same age as Joyce’s hero Stephen Dedalus, though not nearly so well educated. I had working-class New Jersey to thank for that. Joyce’s Stephen had his narrow Ireland, “the old sow that eats her farrow,” as Dedalus describes the country of his birth in his monumental colloquy with his friend Cranly in the penultimate section of the novel — Ireland with its strident priests, dour schoolmasters, inebriated fathers, and demanding God. But also with its classical curriculum.

My New Jersey was much less forthcoming with its lessons. We had no England bearing down on us, only Manhattan, twenty miles away and across the river. That was almostenough. City life set a standard for us on the west bank of the Hudson, and as soon as we were able we made foray after foray into Manhattan, at first by bus, or by ferry over to Tottenville on Staten Island, and then by rapid transit — the “rattletrap” — to the ferry to the tip of Manhattan. And then up the borough by subway — or, on glorious autumn or spring days, by foot.

Standing up on that jouncing train, I read Portrait for the first time. I had already tried some Faulkner and a high-school chemistry teacher had snatched a copy of The Sound and the Fury from my hand during study hall. “Seedy book,” he said, refusing to return it to me until the end of the day.

Portrait was worse than seedy. Some Catholic kids I knew told me it was listed together with Dubliners and Ulysses on the dreaded Index of books good Catholics shouldn’t read. That first time around I had no idea why Catholics might consider it worth banning. As far as I read I had found no obscenities or even euphemisms for obscenities as in the substitution of the coinage fug for fuck in my coveted copy of The Naked and the Dead. (“Oh,” critic Diana Trilling is supposed to have said upon meeting Mailer at the publication party of his grand novel, “You’re the young man who doesn’t know how to spell fuck!”) The hellfire sermons seemed to me something Catholics were accustomed to. I just had no idea.

After my sophomoric reading of the book I finally understood why the book might have been “indexed.” The story of young Stephen’s progress from tormented but assiduous Catholic to budding aesthete stands against everything the church would have him believe, even as his serious Catholic education prepared him for arguing on behalf of his aesthetic. Without Aquinas and Augustine, Dedalus might have tarried longer in the chapel. But with Aristotle and the theologians as the wind at his back he moved faster and faster toward his vocation as a writer — that is, toward the point at which he could look back and write the story of his life and education.

The essential self-reflexiveness of this narrative education was lost on me that first time around. I read for the story, as all naïve readers do, and God save the naïve reader in us, I loved the opening pages, got lost in the family discussions, skimmed through the middle section until the retreat sequence and was mesmerized by the depictions of a hell no Jewish kid ever was raised to believe in — and then I settled in to the torpors of Dedalus’s sinfulness and his subsequent evolution into the aesthete of all aesthetes. I could not have imagined in what good stead the discussion of beauty and its component parts with his university friend would stand me over the years.

The long flowing pages of epiphanic wonder close to the end of the novel more than repaid the squint-eyed attention I gave to the more scholarly parts. The beautifully noticed details from the “eyes of girls among the leaves” to the louse crawling over the nape of our hero’s neck made up a world I might have felt but never could have imagined.

O Jersey boy! Or should I say, Oi! You there, standing before the gates of the 1960s, trembling book in trembling hand! What a connection to make! To feel more kinship with a fallen turn of the century Dublin Catholic aesthete than with one’s own family and friends!

My first reading, though exciting and stirring, was incomplete. Over the years I would return to it many times — the way this novel repays the returning reader makes it an exceptional invention. Other novels beckon, but none like Portrait, none has the same effect, none more instructive for the would-be writer about the pain of education, the struggle with family, the search for a vocation, the vision of a world more beautiful than one ever could have imagined if it weren’t for that vocation opening one’s eyes and allowing one to write about what one sees and feels and hears and touches and tastes — this dazzling novel, a first love that happens over and over again.

__________

Editor’s Note: “A Portrait of a (Would-Be) Jersey Artist Reading A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man” is modified from a version that first appeared in the Autumn 2006 issue of The Sewanee Review.

Some Conversation With Roy Kesey About Pacazo

Pacazo takes its title from a large lizard indigenous to Peru, what on the first page is described as “nothing but an uncommonly large iguana.” Our hero of the novel, however, prefers “to believe [the pacazo] is some imp of history, coincidence made scaled flesh, a god no one worships anymore.” This dual interpretation, conflicting between the dullness of common present and romanticization of heroic past, is just one of the many currents stirring beneath the surface of the book.

Through college and some few years after, I regularly wrote music reviews. This took me to concerts 2-4 nights a week, and I could rely on receipt of a couple promo CDs each day. Having absorbed that volume of music means that, even now, any record or live show is diluted, watered-down. It takes something truly extraordinary in a record for it to rise above the rest.

The same holds true for books, of course. On more than one occasion I’ve remarked that the more I read, the more I learn what I haven’t read. But as with records, there does occasionally come along something that breaches the surface of all that dilution, and when it does, it must, naturally, do so at a higher level.

I think it was March that I first read Roy Kesey’s remarkable novel Pacazo, a 500+ pager that rose up and knocked me flat. I read it over several sittings, while wading through the regular assortment of chapbooks and magazines on the bedstand. Over Memorial Day weekend I dove in again, but this time on a beach in Long Island with only beers and kelp-plucking seagulls for company. Kesey makes time and language something like liquid in the book, and I wanted to do this second read without distraction, to do nothing but drink it in and focus on how the hell he pulled it off.

I could happily drown in this book, is what I’m saying.

Pacazo takes its title from a large lizard indigenous to Peru, what on the first page is described as “nothing but an uncommonly large iguana.” Our hero of the novel, however, prefers “to believe [the pacazo] is some imp of history, coincidence made scaled flesh, a god no one worships anymore.” This dual interpretation, conflicting between the dullness of common present and romanticization of heroic past, is just one of the many currents stirring beneath the surface of the book.

Floating messages between New York and Peru these last few months, Kesey and I did our best to go a bit deeper. . . .

* * *

Joseph Riippi: Put bluntly, one could say Pacazo begins as the story of a man tortured by his past, but who seeks guidance or solace in the history of his adopted homeland. I’ve never been to Peru, but the book nevertheless left me with the impression of a deep, richly historical place. What was it about the country and its history that led to your writing this novel?

Roy Kesey: It’s interesting to me to hear it framed that way. Our Hero (OH) spends much of the book fairly sure that he doesn’t need guidance, and doesn’t deserve solace; but you’re right, there are senses in which he nonetheless turns to history for both straight and twisted versions of both. That throat-clearing aside: yes, unquestionably, Peru is (like most places, I suspect) neck-deep in complicated, fascinating history, and somehow I managed to spend the first 8 drafts (read: first 9 years) of the novel running away from that fact. That’s how long it took me to realize that I needed to embrace history (or histories, really: national and regional and familial and individual and linguistic and et cetera) as content, and also as structural conceit, if the novel was going to fulfill the hopes I’d had for it starting out.

Or, if the question was Why Peru instead of Ecuador or Kenya or Sweden or Malaysia?, then: Peru is where I was (and am, for the time being.) Life gifts you access to certain things, and you can make use of them, or go off looking for other things. Like most writers, probably, I do a bit of both for each book, but this one is grounded in a place (not just Peru generally, but northern-desert-coast-of-Peru specifically) that I knew well in actual day-to-day life, which, while not exactly essential, rarely hurts, in my experience.

Or, if the question was In what sense did Pacazo become what it is precisely because it’s set in Peru? (as I’m now suspecting it [the question] was all along — I’m a little slow), then: that’s one of the questions to which the novel itself is the answer. But just to sort of tug at one thread as an example: what does it mean for your psyche and life when almost all of your National Heroes died in battles subsequently lost?

JR: What you do with language and time in the first chapter is remarkable. The narrative often moves mid-sentence and within present tense, from modern Piura to centuries-old explorers. You write in that chapter, “In Spanish, tense and time are a single word.” With language so important to this work, I’m interested how you think the limitations and/or advantages of English over Spanish affected the story you told?

RK: Thanks. Also: I have a terrible feeling that any legitimate attempt at an answer to this question would run a hundred pages. Plus footnotes. Plus indices. But, so, okay:

There may well be ways in which one could occasionally speak meaningfully of the advantages of one language over another for a given task or field, but those ways are, I suspect, a lot weaker and fewer in number and in the end less interesting and less useful than one might guess. And that question (i.e. about the relative betterness of a given language in a given context) wasn’t really one I was trying to ask in the course of writing Pacazo. I was more interested, I guess, in playing in the neurolinguistic intermuck where (some) long-term expats pitch their tents.

That is, the book takes place almost exclusively in English, which happens to be OH’s L1. Now, he does great work in Spanish, his L2, but it (his L2) (along with a bunch of other things) is messing with his L1 (and with his brain more generally) in what I hope are interesting ways. For example, because language matters to him, and (in part) because translation and interpretation and TEFL are constants in his workaday world, he often comes up against the fact that some of the English phrases that most native English speakers use regularly make no literal sense, and at times make anti-sense, which can (a) work against any sort of clarity, but also (b) be kind of weird and beautiful. There’s also the question of his students’ L1-induced English errors, and the eddies those errors create in OH’s mind. And the question of the neural consequences of the more experimental Spanish he reads — the Oquendo de Amat poems, etc. Plus also the question of regionalisms in the Spanish he hears every day, of which the title is one — their place within Spanish generally and Peruvian Spanish specifically, et cetera. Plus also et cetera.

So that’s one level of it. Another is where you’d find the technical or logistical matters that interested me as I was working on the novel: how to have the question of which language a given character is speaking at any given time be perpetually clear for the reader but (almost) never overtly addressed, for example. Another example, one still closer to my heart, maybe even inside it, like cholesterol, blocking arteries left and right: the question of how to rid the world of interlingual italics. This has become an absurd little crusade of mine. It drives me crazy, this “the campesino ate an empanada outside the hacienda” business (and I owe that example, however misquoted, to Paul Theroux — wish I could remember which book it was — maybe the Patagonian Express one?). So I have taken it upon myself to convince all current and future writers to join me in repeating, cultmantra-like: All Non-English Words Become English Words The Instant I Use Them Unambiguously In An Otherwise English Text! And Thus (With The Help Of A Retroactive Microsecond’s Worth Of Magic) Do Not Need Italics! Plus Also Now The Entire English Corpus Has Shifted Toward The Other Language’s Corpus, And Vice Versa! (And The Same Goes For Whenever An English Word Is Used In An Otherwise Non-English Text!) And All This Is A Good Thing! Because Of Empathy! Et Cetera!

My next two absurd little crusades will involve stamping out the use of exclamation points and non-standard capitalization, respectively, naturally.

JR: I am almost sure it’s the Patagonian Express one you’re referring to, but it’s been awhile since I read that. Theroux has enough books it might be in multiple.

One last question / thoughtfodder-catalyst, because it seems it only took a couple questions to get a rather wonderful bit of thoughtfodder on the page: When I first sat back from Pacazo and breathed and considered it in the context of your other work, I thought immediately of the story “Wait” from All Over, in which airline passengers are kept captive by the weather in an airport terminal of purgatorial limbo. Would it be fair to compare Our Hero’s memory of his wife with that fog, keeping him in a sort of misguided purgatory? To be grand, I could see extending that personal past to a nation’s historical / social past, clouding the direction home, obfuscating us as nations / societies from getting anywhere. In your story “Invunche y voladora,” too, also from All Over, there’s a disconnect between the newlywed couple’s anticipation / expectation of their South American honeymoon and the reality of the days, a reality which may continue to the future of the marriage. Am I just italicizing hacienda here, or is this a theme you’re consciously engaging with when you sit down to the crusading?

RK: During the actual crusade-type crusading, the hardcore first-drafting, there’s no themework at all — you’re just doing what you can to follow the voice, thinking with your hands, the vorpal blade, valley of death, et cetera. But then afterwards, when you’re icing down those tendons, and securing victuals against the fact that ‘vorpal blade’ made you think of ‘snicker-snack’ which made you hungry, you survey the field, and sure, sometimes the bodies lie in patterns that please you, patterns that can be made sense of, and sure, what the hell, let’s call those patterns ‘themes.’ At which point you finish up your snickerdoodles and mingle with the mess, adjusting a severed head here and a fallen standard there, palpating this wound and stretching out these bowels just a tad, not so much (in my experience) in the interest of clarifying the themes, exactly, (though sometimes that too,) as of complicating them in ways that will (if all goes well) get them (if you will) talking amongst themselves.

Now. Are there certain questions I return to? Sure. Am I — to take your premise gently by the hand, look deep into its eyes, and smile just so—absurdly interested in the means we employ in our (successful or unsuccessful, makes no never mind) attempts variously to deal with / conquer / ignore / escape / endure / tunnel through / vault / sidle past That Which Obstructs Us? Yes, yes I am. And will That Which Obstructs Us have landed in our path having leap-frogged us from some point in our past? Not necessarily, but sometimes, probably — maybe even most of the time. As to whether a specific set of circumstances will occasion an attempt requiring the use of a luggage carousel, a hot air balloon, a bus ride into the highlands or something else entirely, I submit there is no knowing in advance, least of all for this writer hisownself.

Breaking Bones for Meaningful Marrow: A Review of Chuck Palahniuk's Fight Club

Like many people, I discovered Chuck Palahniuk’s 1996 debut novel, Fight Club, after seeing its film counterpart (released in 1999). I loved the absurd sexuality, violence, and profanity of the film (which, considering that I was 12 years old, made me a stereotype). I thought that the book would be equally awesome. And it was. However, while most of my peers enjoyed only these same superficial qualities, I recognized that there was more to Fight Club. A lot more.

Like many people, I discovered Chuck Palahniuk’s 1996 debut novel, Fight Club, after seeing its film counterpart (released in 1999). I loved the absurd sexuality, violence, and profanity of the film (which, considering that I was 12 years old, made me a stereotype). I thought that the book would be equally awesome. And it was. However, while most of my peers enjoyed only these same superficial qualities, I recognized that there was more to Fight Club. A lot more.

Fast-forward ten years and I’m currently teaching Fight Club at the same university where I earned my BA two years ago. I chose to teach the book for three reasons: (1) it is ripe for discussion, (2) it was pivotal in my decision to become a writer, and (3) Requiem for a Dream is too complex structurally and American Psycho is way too violent (right?). In any case, I felt confident that Fight Club would provide enlightenment, engagement, and entertainment for my students.

The main themes Fight Club examines are the soapbox effect of religion and the horrors of cult mentality. Fight club begins one night when the narrator and Tyler start beating each other up outside of a bar. Eventually, they hold meetings in the basement of another bar, and week after week, more and more people come. Tyler and the narrator compile a list of rules, and we’re told how men from every walk of life exorcise their demons and frustrations by beating each other. They’re rebelling against conformity and society. The narrator says, “fight club exists only in the hours between when fight club starts and when fight club ends.”

Eventually, the members wear their bruises and stitches (as well as Tyler’s burned kiss, which is an entirely different issue) like badges of honor; they’re committed to the club. As the novel progresses, Tyler begins starting more and more fight clubs without the narrator’s knowledge. About halfway through the book, the narrator meets an old friend, Big Bob, whom he knew from a cancer support group. Bob informs him that he no longer goes to support groups because he’s found something better:

“there’s a new group . . . called fight club . . . it meets every Friday night. . . . On Thursday nights, there’s another fight club . . . the rules [were] invented by the guy who invented fight club. . . . I’ve never seen him myself, but the guy’s name is Tyler Durden. Do you know him?”

Naturally, the narrator has no idea that Tyler is starting a cult, and eventually, fight club becomes the catalyst for Project Mayhem (and then the sh!t really hits the fan!).

While examining religion and cults through subtext would be enough for one novel, Palahniuk doesn’t stop there. He also criticizes American materialism, considers self-preservation vs. self-destruction, and combats injustice within social hierarchy. Oh, and he interweaves the foundations of Marxism with the foulness of mixing food with bodily fluids. It’s simultaneously perverse and profound.

Going beyond its social commentary, Fight Club is notable for its brilliant (and arguably impossible) twist. Throughout the book, the skewed relationship between Tyler and the narrator is complemented by ambiguous statements and odd symmetry. Once readers understand what’s really going on, everything changes, and it’s fascinating to reread the book and discover all the foreshadowing and symbolism Palahniuk places so smoothly. As my classes and I discuss the book every Monday afternoon, I’m consistently amazed at how lines like “Tyler’s words coming out of my mouth” and “If you ever mention me to her, you’ll never see me again” go completely over their heads.

While Fight Club isn’t technically Palahniuk’s first novel (his third, Invisible Monsters, actually predates it), it’s likely his most complex and important. Underneath all the depravity, violence, and dark, dark humor, Palahniuk investigates human nature and critiques the way we live our lives.

If you would like a peek into the dreary future of social networking, you should read this book.

The desocializing effect that Facebook and Twitter have, the dichotomy created between online and “IRL,” and the nurturing of the self-absorbed ego that now occupies the center of attention in your own social network are all usually jokes; the kind made about your friend who spends too much time online. But those jokes take on a real value in Michael J. Seidlinger’s new work In Great Company.

We live in a bizarre generation. That is a fact. The awe and confusion that older generations have in the face of our quick-adapting, technologically saturated youth is immeasurable. It is also something well noted; nobody denies the reality that we grow up now immersed in technology or that information is increasing at an insanely exponential rate. Something that is perhaps less seriously mulled over is the effect of this culture on the personalities of today’s youth. The desocializing effect that Facebook and Twitter have, the dichotomy created between online and “IRL,” and the nurturing of the self-absorbed ego that now occupies the center of attention in your own social network are all usually jokes; the kind made about your friend who spends too much time online. But those jokes take on a real value in Michael J. Seidlinger’s new work In Great Company.

In Great Company is a bizarre book. It wavers between being the personal journal of a guy obsessed with his various internet handles and the battle log of a commander at war, self-indulgent and intent on destroying everyone around him. It is easy to hate the narrator of the text. He, himself, comments on that often. But what he is demonstrating is important and the hatred perhaps comes from a minor degree of self-recognition (and latent self-loathing). Seidlinger has created a character that takes all of the qualities that I suggested earlier (effects of the Internet) and develops them to extreme levels. The disgust provoked by this character, in my case, is really a fear of becoming him.

Early on the narrator professes: “I can only / Quantify moments here, online.” The absorption of the self into an identity on a social network is the only real “event” in the text. Nothing is happening externally. The action is all within the narrator. He speaks to this transformation from human to handle frequently and alludes to an inability to reintegrate into life outside the web with satisfaction: “I am counting / On the unpredictability of the / Digital surf to give me the / Experiences I can no longer get / On my own.” The easily felt repulsion for this character turns into sympathy when you start to look upon him as a social eunuch, removed from the joy of engaging in real-world, fruitful interaction. You can further poke holes in this self-absorbed identity via the errors in the text (mostly, typographical; likely, unintentional), a further reminder that the intimidating voice that speaks is human after all, and like many college-degree bearing students who majored in English or creative writing, he makes typos.

As the text progresses, the confusion between cyber identity and real life intensifies, particularly with the introduction of the “virus.” A trifold interpretation of “virus” as a literal ailment that is contracted and spread, a digital corruption that likewise infects, and as a social disease of cyber obsession (the undoing of the normal functioning personality) makes the narrator’s (and most young readers’) condition very real. The hyper formation of a constructed identity eventually culminates in the loss of identity: “I / Can see my skeletal features, / Looking back at me, when I / Look, I look fearlessly. Go / Ahead, do the same . . . You see the outline of your / Skull?” This skull-like face graces the cover of the book, a sort of dark, apocalyptic version of that blue, outlined head on Facebook.

The risk of defacement, self-absorption, and losing touch with reality has given way to many of the greatest texts in literature. Noah Cicero related In Great Company to Dostoyevsky’s Notes From the Underground. It also reminds me a bit of Augusto Roa Bastos’ novel I The Supreme. But where these novels demonstrate a certain personality type and condition that are universal, the circumstances surrounding them don’t hit close to home for most contemporary readers. That is why In Great Company is so disconcerting. Its circumstances are those that surround the majority of us in this day and age. Its suggestions are possibilities perhaps too real for people aged thirty or younger.

If you would like a peek into the dreary future of social networking, you should read this book. The warning is that you may come out of it feeling a little “disembodied” or “skeletal.” If you don’t, then you are probably in severe self-denial.