The Panorama of Dust Returning to Dust: A Review of Eric Shonkwiler's Above All Men

Amid stark praise for Above All Men’s uncanny breathing of life into the Midwest is the irony that in order to accomplish this, Eric Shonkwiler shows us how the Midwest finally death-rattles and dies.

Amid stark praise for Above All Men’s uncanny breathing of life into the Midwest is the irony that in order to accomplish this, Eric Shonkwiler shows us how the Midwest finally death-rattles and dies. Eric Shonkwiler’s debut literary fiction novel, Above All Men, puts beneath a cracked magnifying glass the panorama of what dust returning to dust could really look like.

I’m not a book reviewer. I find it difficult to convey honestly how a book hits me to people who have not read and experienced the same things I have. It’s a lot like music that way. This makes writing a book review seem like a hell of a task from the front end, and I seldom find a book that grabs me enough to warrant the time and effort it takes me to write and place a review. In saying this, I hope it’ll serve as a preface to my maybe covering some aspects of Shonkwiler’s writing that may otherwise not be highlighted in a typical review, and it will give you an idea of how much this book reached me. Because Above All Men warrants all the time, effort, and honesty I can give it. This guy’s writing is alive.

The book opens with a dream sequence in the mind of protagonist, David Parrish. I’m always curious about how the authors of books/stories I’ve really enjoyed go about finding a place to begin. It would make sense for Above All Men to begin inside of a dream, as the writing style carries on in this ethereal dream state for the remainder of the novel. The barren landscape of a future United States serves as a perfect stomping ground for the figurative ghosts that haunt the novel. And Shonkwiler’s streamlined approach to writing dialogue creates an unexpected accompaniment fit for a haunting; characters’ conversations bleed into their movements and actions in a way that feels, at times, more like verse than prose. Not exposition punctuated with speech, but something more ritualistic. Incantations. Hymns given to rhythm and unencumbered by grammatical tradition. Shonkwiler’s poetry background shines through most prominently in the way his characters talk to one another; they’re following a beat. It doesn’t always work for other authors. It works here.

If a line exists between spoiling surprises by giving away too much detail, and delivering a vague outline by holding back too much detail, I’m not aware of where that line falls. And if I were to have it pointed out for me, I’d more than likely err on the side of not saying enough than of blabbing too much, so I’ll keep the synopsis brief. The story revolves around Parrish, a PTSD-stricken veteran of a future American war fought abroad. Above All Men introduces a post-war Parrish, who’s settled somewhat awkwardly into a role as a farmer struggling to make ends meet and trying to hold his family together. In the midst of scratching to survive in post-collapse rural America, and dealing with food, water, oil, and resource shortages, Parrish must also contend with changing environmental factors that have ushered in a second Dust Bowl. When a child in town is murdered, the death rips open old wounds for Parrish, and he takes matters into his own hands to find the killer and to exact his own form of revenge-cum-justice from a skewed, yet instinctual moral compass.

What we’re given here is a look at a man’s past, how events that befell him before he became a family man come to govern how he moves himself forward after becoming a more active husband and father. We’re given a look at the ties between family, friends, and neighbors, and how quickly those ties corrode away when polite society grinds to a halt. At surface level, David Parrish is a hard-working farmer, a devoted husband, and a father who wants nothing more than to shelter his son from a world Parrish couldn’t keep from dissolving. Just beneath this veneer, however, is the soldier, the David Parrish who found himself, much like Vietnam-era G.I.’s, in a foreign landscape where the strongest currency is atrocity, and where he who possesses the greatest tolerance for taking and inflicting pain is king. The way Shonkwiler duels these two personalities against one another is brilliant. The same man who’d do anything to keep his son from attending a funeral and seeing first-hand the evidence of mortality is just a frame away from snapping into a mode where the most productive tack is violence. Watching this dichotomy unfold, fracture Parrish, and eventually resolve itself in what author Frank Bill calls “sparse and poetic” prose, is nothing short of a rollercoaster, and, for me, the book’s crowning achievement.

Above All Men puts readers front-row for a study in the difference between justice and revenge, and how that difference may exist as a much more fluid entity in a dystopian future than the run-and-gun pundit commentary that pervades our online world. By taking us to the future, Shonkwiler paints a picture, sometimes bleak, sometimes horrifying, of our frontier history. And ultimately, amidst turmoil, lawlessness, panic, fear and doubt, we’re shown that love may not conquer all, but it’s strong enough to compel us forward. That honor may not save a man, but that it can point him in the right direction.

Urgent Possibility: Talking With Lance Olsen on FC2’s 40th Birthday

While many authors, many presses, have gotten this by now in one form or another, it fills me with pleasure and pride knowing FC2 was one of the first in the U.S. to drive down that non-normative road. In many ways, FC2 is responsible for the alternative-publishing paradigm that most small, independent, not-for-profit presses currently deploy in one iteration or another.

Rachel Levy: What has surprised you about working with FC2?

Lance Olsen: One of FC2’s purposes has been and is to rethink the dominant publishing ecology, to try on alternative models. Perhaps one of the things that stays the same about our project with respect to this is that nothing stays the same. FC2 is always adapting to current conditions, transforming, attempting to out-think the present commercial literary engine.

With this in mind, possibly the greatest surprise for me has been the daily discovery of good-spirited collectivity among our Board members, our authors, our interns, our readers, our tribe. I’m speaking here about the idea of literary activism—the realization that writing is only one creative act among many that constitutes a writer’s textual life in the twenty-first century. While many authors, many presses, have gotten this by now in one form or another, it fills me with pleasure and pride knowing FC2 was one of the first in the U.S. to drive down that non-normative road.

In many ways, FC2 is responsible for the alternative-publishing paradigm that most small, independent, not-for-profit presses currently deploy in one iteration or another.

RL: FC2 is committed to keeping all of its books in print, and so, in a way, FC2 is committed to publishing today’s innovative fiction, while also curating (and even maybe canonizing?) a catalogue of texts that may no longer be able to bear that term. Can you speak about this?

LO: I love your idea that FC2 serves as a kind of curator for the innovative, although I would probably change out your choice of noun for another. Perhaps closer to the point for me is that FC2 serves, as I say, as a space of exploration about such perplexing and bracketed concepts as “the innovative.”

That is, FC2—perhaps by some wonderful accident—has kept in play for four decades a polyphonic discourse about that which must be considered the innovative, and can’t be, and can’t can’t be.

RL: How does FC2 operate?

We’re committed to finding new innovative work and expanding our membership even while keeping all the books we’ve published in print.

We look for new work in three ways. First, any FC2 author may submit a manuscript by her or him at any time. Second, an author already published by FC2 may sponsor a manuscript by an author unpublished by FC2. Third, an author unpublished by FC2 may submit to one of our two contests—The Ronald Sukenick Innovative Fiction Contest and The FC2 Catherine Doctorow Innovative Fiction Prize. The winner of the former, aimed at emerging writers, receives publication and $1500, while the winner of the latter, aimed at writers who have already published at least three books, receives publication and $15,000.

In the case of numbers one and two, manuscripts are sent for evaluation to authors previously published by FC2. A manuscript receiving two yes votes before receiving two no votes moves to the Board of Directors—currently comprised of Kate Bernheimer, Jeffrey DeShell, Michael Mejia, Matthew Roberson, Elisabeth Sheffield, Susan Steinberg, Dan Waterman (a non-voting representative from University of Alabama Press, of which FC2 is an imprint), and me (chair of the Board)—for a final editorial decision.

Each year one of the members of the Board of Directors serves as judge for the Sukenick contest. For the Doctorow, a non-FC2 writer of innovative fiction serves as judge; in the past, those have included such authors as Ben Marcus, Rikki Ducornet, and Sam Lipsyte.

For more about the contests and how the press works, those interested can go to our website.

RL: What is FC2’s relationship to digital writing? Does FC2 think about showcasing more digital and new media works? What are some of the challenges FC2 might face in committing to such an endeavor?

LO: I’m delighted FC2 has had the opportunity to bring out Steve Tomasula’s stunning hypermedial investigation into the nature of temporality, TOC. It was our first complexly digital work, and we all assumed many more would quickly follow. Interestingly, that hasn’t been the case. We haven’t yet found ones that capture our imaginations as fully as Tomasula’s did. But we keep looking, keep hoping that changes soon.

The biggest challenge with respect to bringing out new media work has to do with distribution, with disseminating the word, since the channels of dissemination don’t work the way those for print books do. But, as we saw with TOC, those challenges are not by any means insurmountable, given enough time and the deep understanding that such works are—unlike the codex—profoundly and profitably (in aesthetic—not economic—terms) ephemeral.

RL: FC2 author and former publisher, R.M. Berry, said in an interview: “When you get into work that’s really groundbreaking the norms aren’t established by which you can know is this good? Is it incompetent? It’s often the case with really radically challenging writing that the editorial process of making a decision to invest in this kind of work is really, really difficult.” Do you also find this to be case? Given the radical nature of the manuscripts that come FC2’s way, how does the board negotiate the difficulty of establishing criteria for what’s “good,” or even for what’s a “good fit” for FC2 when deciding on whether to publish or to pass on a potential manuscript?

LO: I sometimes make the editorial process sound cognitively heavy, and sometimes it’s that—a long hard intellectual discussion that attempts to discover a way to talk about a crazily, excitingly heretical manuscript. Often, however, the conversation among the Board members begins much more intuitively. Something catches a Board member’s interest or passion, and the conversation tries to find a means to capture that intuition in language and logic. It’s seldom the case that the result is a unified position among Board members. Rather, as chair I’m looking for consensus while understanding the capriciousness inherent in the idea of fiction misbehaving.

RL: On fc2.org, you have an essay titled “Narratological Amphibiousness” in which you talk about innovative writing practices. That piece strikes me as both a personal manifesto and an exploration of FC2’s project. If you were to write a micro-version of it today, what would you say?

LO: Narrativity that refuses impermeable boundaries constitutes an urgent possibility space that should encourage us all to ask: How does one write the contemporary? Each of us, needless to say, will answer the question differently.

Night of the Living Bildungsroman: A Review of J.R. Angelella's Zombie

Of all the subsections and structural variants that have graced the literary landscape over the years, the bildungsroman (coming-of-age story) is perhaps the most treasured and adaptable. These pieces vary greatly in terms of intended audience, genre, and tone, and you’ve no doubt seen examples both in classic works (Great Expectations, Candide, Jane Eyre, To Kill a Mockingbird, and Catcher in the Rye) and newer fiction (The Kite Runner, The Perks of Being a Wallflower, Persepolis, Harry Potter, and yes, even Twilight to some extent. Sorry.)

Of all the subsections and structural variants that have graced the literary landscape over the years, the bildungsroman (coming-of-age story) is perhaps the most treasured and adaptable. These pieces vary greatly in terms of intended audience, genre, and tone, and you’ve no doubt seen examples both in classic works (Great Expectations, Candide, Jane Eyre, To Kill a Mockingbird, and Catcher in the Rye) and newer fiction (The Kite Runner, The Perks of Being a Wallflower, Persepolis, Harry Potter, and yes, even Twilight to some extent. Sorry.)

Zombie, the debut novel by J.R. Angelella, earns its place on the list easily, as its narrator (Jeremy Barker) is all too happy to discuss his jaded outlook, troublesome adolescent experiences, and quirky family, friends and enemies with superficial humor and touching emotional subtext. His is a tale we can all relate to (well, sort of. You’ll see.) In fact, Barker is clearly a spiritual successor to Salinger’s Holden Caulfield — both deal with “phony” adults, sexual inexperience, violent psychopathic fantasies, confusion about love, and anxiety about life. The chief difference here is that Barker also has to deal with snuff films, an emotionally void, drug addicted family, and plenty of psychical altercations at school. Oh, and zombies. Lots and lots of zombies.

Interestingly, the book begins with Jeremy discussing his father’s penchant for and judgment of neckties:

According to my father [Ballentine], there are three types of necktie knots: the Windsor, the Half-Windsor, and the Limp Dick.

Afterward, we are privy to various subtle yet revealing discussions and interactions between them, including overly explicit details about how said knots imply masculinity, the whereabouts of Jeremy’s mother, and hypothetic zombie survival scenarios (it’s with these details that Angelella evokes Palahniuk and Ellis). It’s here that we get a strong sense of their complex relationship, as their wildly different personalities (Jeremy, a perverse, talkative kid ripe with imagination; Ballentine, a stubborn, quiet and disinterested adult who treats his son like a soldier) get in the way of their bond. There’s a love between them, but it’s masked by secrecy, cruel expectations, and unreturned affection. Jeremy spends much of the novel trying to get closer to and make sense of his father, and this struggle shows how Angelella manages to place touching human conflict underneath superficial humor, obscenity, and gore.

It’s also in this first chapter that we learn of Jeremy’s five Zombie Survival Codes for a zombie apocalypse:

ZSC #1: Avoid Eye Contact

ZSC #2: Keep Quiet

ZSC #3: Forget the Past

ZSC #4: Lock-and-Load

ZSC #5: Fight to Survive

Of course, he acknowledges that he stole these rules from the film Zombieland (in fact, the book is full of allusions and commentary on actual zombie films, which is a nice touch). As you’d expect given the context, these guidelines protect him from, well, everyone else, and the way he uses them as psychological and emotional defensive mechanisms is tragic yet relatable. If you’ve ever dealt with a broken home and/or high school bullshit, you can understand his perspective.

As for the rest of his family, well, we see a bit of his drug addicted mother, Corrine, her peaceful new man, Zeke, and Jeremy’s womanizing, avant-garde brother, Jackson. Honestly, we don’t see much interaction between them, so they serve more as archetypes than actual characters. Nevertheless, further exemplify why Jeremy feels so bitter and disenfranchised.

Fortunately, there is a bit of hope for Jeremy, as he finds three objects of teenage attraction: Tricia, Franny, and Aimee. The former is college age and lives next door to him; she essentially offers him advice and then flashes him through her bedroom window at night (you know, the typical neighborly bond). As for Franny, she’s a bit older, and she seems to find a kindred spirit in Jeremy. Aimee proves to be the most important of the group, as she gives Jeremy the confidence and affection (eventually) that he so desperately needs (that is, when he isn’t getting nose bleeds every time she walks by). She comes from a Mean Girls background yet finds Jeremy’s awkwardness and genuine sincerity endearing. They share many charming moments, such as the following:

We stand shoulder-to-shoulder, holding hands, looking out into the abyss of the harbor. I can see Federal Hill across the way and the lights of ‘The Prince Edward.’ Sailboats and speedboats drift along, spotting the black hole with dots of light.

“I wish I could press pause right now,” I say, putting ‘Little Man’ on the floor.

“That’s sweet.” Her fingers lace further into mine.

“I want to be happy,” I say.

“That’s not asking for much,” she says.

“And I want you to be happy too.”

As for the advertised subplot about “a bizarre homemade video of a man strapped to a bed, being prepped for some kind of surgical procedure” that leads Jeremy to “a world far darker and more violent,” well, it’s not as crucial or established as you’d probably expect. There are a few remarks about it, and it does put even more distance between Jeremy and his father, but overall the core of the story revolves around the aforementioned relationships. The end of the novel, however, deals with it directly, and while the resolution is a bit too quick, it’s still a satisfying exploration of cultism. Also, the irony of Jeremy loving zombie films yet being disgusted by real violence is a clear statement on how desensitized people can be to torture.

To be honest, Zombie is not without its faults; the profane and immature language Jeremy uses feels inauthentic at times (you can tell it was written by a man trying to write the voice of a teenager), and just about every one of the plot points I mentioned earlier is underdeveloped. In other words, we have glimpses of a dozen ideas instead of a dedicated and fulfilling examination of, say, three of them.

Still, I haven’t finished a book this quickly since I first read American Psycho (in three days). There’s just something about the narration and events that suck you in and keep you reading. Despite all of these flaws and the narrator’s repetitious thoughts (how many times can we be told about the ZSCs?), Jeremy is a very likeable protagonist. You root for him, laugh at him, and most importantly, feel his pain every step of the way. In the end, Zombie isn’t an especially complex or rewarding read, but it is a vastly entertaining and charming one. It stays with you long after you’ve read it, and really, that’s the ultimate goal for any work of art.

At Times, I Felt Like I Didn’t Even Recognize Myself: On Sophie Kinsella's Remember Me?

All in all, Remember Me? is a fun and light read. It is definitely no literary classic, but it made me laugh to myself many times, and once it was over, it made me think about what kind of future I wanted to create for myself. I

I was fourteen years old when I first read Remember Me?. The large iconic sunflower on the book’s front cover caught my eye one summer afternoon as I strolled through the books aisle of a wholesale warehouse while my mother shopped for vegetables and juice. I didn’t know it then, but I was looking right at the book that I would later consider one of my absolute favorites. Several years later, I still can’t pinpoint the precise reason why I felt so drawn to Kinsella’s novel. I can say, however, that the two very words of the title spoke so clearly to my desires at the time.

Growing up, friends and peers moved in and out of my life constantly. It started in the fall of the third grade when my best childhood friend moved away, and would continue up until high school. I attended a middle school none of my elementary school friends attended, and I was bracing myself to attend a high school none of my middle school friends would attend. Time after time, I had to rebuild my social ground, and being on the introverted side, I found it quite wearing and disorienting. I felt undeniably lonely, yet secretly frustrated at my peers for never remaining constant in my life, even though I knew they weren’t to blame. I was tired of not recognizing anybody, and in turn, nobody recognizing me. At times, I felt like I didn’t even recognize myself.

I’ll admit that I had this absurd recurring fantasy in which one day, when we were all older and I was successful and living abroad, I would visit my hometown, walk down the street and eye a group of my old peers laughing and joking to each other about their mundane lives and kids and jobs, then they would see me, too, and halt in their tracks. I’d strut up to them, jut my chin up high and say, “Remember me?” Then they would freak out and remember neglecting me and sob about their regret and swear never to ignore me again and then ask sheepishly if maybe they could work for me for the rest of their sorry little lives. I realize now that this rather vicious daydream of mine is foolish, cocky, and totally impractical, but back then, it was my driving force to be “better” than other people, to accomplish more and higher than anybody I’d ever known. I was The Little Engine that Wanted to Could, and I wanted it bad. So did, as it turned out, Lexi Smart, the protagonist of Remember Me?.

Glancing over the front cover of Remember Me?, I felt a heated medley of all these inner resentments churn and bubble within my heart. I just had to read it. I asked my mom if she was willing to buy it for me, and she did, since she was always happy for me to read on my own. I sat down on my bed that evening and cracked open my paperback copy, and thus marked my first step into the world of twenty-eight year old Lexi Smart, and boy, did I enjoy the ride. I enjoyed the ride so immensely that I would read it through another seven times over the following three years. I remember staying up late many summer nights just so I could relive Lexi’s tale of when she woke up one evening in a London hospital to a big surprise: herself.

Upon regaining consciousness, Lexi discovers that she has straight teeth, a toned body, amazing nails, and a business card that reads “Director” of the company for which she used to be a junior assistant manager. She lives in a trendy new loft with her handsome, multimillionaire husband, and has her own personal assistant. The doctor tells Lexi that she survived a car crash in which she lost memory of the past three years, so she has no idea how her life could change so dramatically. Her most recent memory was the night she ranked a “minus six…on a scale of one to ten”, when she was still twenty-five years old. She was just a week shy of a yearly bonus at her new job, was stood up by her boyfriend, and was preparing to attend her father’s funeral the following morning. She remembers lamenting desperately for her life to improve, and it seems that it has finally happened; as if by magic, she’s living her dream life.

Lexi tries to hold onto this glamorous image of her new life, but the more she learns, the more her life turns out to be not quite what she originally thought it to be. Her sweet, innocuous twelve year old sister is now a rebellious, swindling teenager; her lifelong friends insist that she is a “bitch boss from hell”; and her husband is in love only with Lexi’s businesslike façade. And on top of all that, she is apparently having an affair with her husband’s architect, Jon, who later confronts her about it. As Lexi slowly pieces together the past three years of her life, she comes to discover how and why these drastic changes in her life came to be. Once the bigger picture of her life materializes, Lexi must ultimately decide whether she wants to keep her present life or find the strength within her to change it to suit her own accord.

What really struck me about Remember Me?, even after my first time reading it, was that twenty-eight year old Lexi from before the car crash was secretly unhappy with this glamorous lifestyle, and it was an idea my then fourteen year old brain had trouble grasping. I didn’t understand fully why until I reread the novel years later. Yes, she was stinking rich, but she was unloved. Nobody really understood her. When she was being simply herself at twenty-five, she was dreadfully unhappy with current prospects of her life. She was fed up with always drawing the shortest straw, so she decided to undertake the most extreme of makeovers. She fostered an austere businesslike persona she thought all successful people had and used it to climb out of the hole she was in. She knew it wasn’t really her, but if that attitude was her ride to the top, she would hop in and floor it. She let it overtake her, and that was the mask her husband fell in love with. Reaching the summit was all she could think about, for reasons explained towards the end of the book, but in doing so, she lost perspective of other more important areas of her life. She had gone too far in her blind pursuits and ended up where she knew she didn’t belong, not deep down inside. It’s no wonder she sparked an affair with the architect. She was lonely.

Perhaps what struck me even more was that this memory loss what just what Lexi needed; perhaps the past, more genuine Lexi could offer a fresh perspective on her current lifestyle, a solution to her problem. Talk about a blessing in disguise.

All in all, Remember Me? is a fun and light read. It is definitely no literary classic, but it made me laugh to myself many times, and once it was over, it made me think about what kind of future I wanted to create for myself. I empathized greatly with Lexi, and eventually, I realized that I had a Lexi Smart within me as well, one who dreams of a better tomorrow, but may not quite know where to start.

At one point in the novel, Lexi explains, “I feel like I’ve been plonked in the middle of a map, with one of those big arrows pointing to me. ‘You Are Here.’ And what I want to know is, how did I get here?” This lost, confuzzled feeling is one I have felt many times, and this is always how it starts when we begin to question our own direction and motives. Remember Me? is about being and becoming, about taking time to reflect on the trajectory of our very lives. Do we see a beautiful future on the horizon, or are we sailing in the wrong direction? Only we can decide for ourselves what we truly want, and Lexi struggles through the process of leaving marks on her own life that, upon looking back, she can be happy with.

So, did the book I saw one summer afternoon I strolled through the books aisle of a wholesale warehouse while my mother shopped for vegetables and juice satisfy me? Yes it did, but more than that. It taught me the right way to learn about myself; just like Lexi questioned herself, I learned the importance of questioning my own goals and choices so that I can be who I truly desire to be while remaining honest with myself. That truly is a valuable lesson.

The real gold of this book lies in the protagonist, Lexi, and tagging along with her as she interacts with others and tries to piece herself together. What she learns may surprise you. Sit back and listen as Lexi introduces her brand new life not only to you, but to herself as well; Sophie Kinsella’s Remember Me? is a peep of sunshine that will surely try its best to brighten your day.

His Stumbling, Almost Dream-like Existence: On Cody James's The Dead Beat

The Dead Beat is a coming of age story for the slacker generation — surely, this being what some might label as Slacker Fiction—those who find themselves between great swathes of adulthood (school and careers, namely), unstuck in time with nothing but (little) money to burn and carnal instincts to explore.

The Dead Beat is a coming of age story for the slacker generation — surely, this being what some might label as Slacker Fiction—those who find themselves between great swathes of adulthood (school and careers, namely), unstuck in time with nothing but (little) money to burn and carnal instincts to explore. It sheds light on a particular foursome of dysfunctional twenty-somethings, childhood friends—not just meth addicts, but addicts of alcohol, of themselves . . . addicts to wasting away — and The High, not only from drugs, but from various facets of life, the relationships they take for granted (as we all do) and reform (again, as we all do) and others we cultivate from chance meetings. From living on the fringe, from not being a sellout and doing your own thing.

There aren’t many likable characters here, which isn’t necessarily a novel approach towards an empathetic audience (see, for instance, every character in Ellis’ Rules of Attraction, various Updike novels featuring Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom, Leopold Bloom from Joyce’s Ulysses), but somehow you find yourself smiling at the antics of it all. Even though these people may be a far cry from you, there are parts of them you recognize in yourself and in your generation. These friends — lead by the affable-yet-burned-out one-time writer Adam, our guide into this world of debauchery and apathy — are addicts, users, and the story follows them, through their ramblings, through their few ups and many downs, seeing their friends suffer but doing nothing, standing idly by as the world, the lives they had once planned out, pass them by.

There are moments of clarity in the book where Adam “wakes up” from his stumbling, almost dream-like existence, and as much as we want him to kick his habits and grow up, he doesn’t. You realize this is real life, not any sort of make-believe, and there are people out there, in every city, in every town, just like this. It’s not easy to kick habits so engrained in you—and it’s the lifestyle in general, not the specificities of the lifestyle. Their daily regimens, what they have grown to expect out of life, has molded onto them like some second skin and can’t so easily be picked off. Only in the last few paragraphs do we see a change in a few of them after a heinous event transpires, one that, potentially, could rocket them all on the path to righteousness once and for all.

But then the book ends. It’s gone. And we don’t know what actually does happen at this pivotal turning point: Do they see the error of their ways, the irreparable damage they’ve caused their bodies and their minds and move on, or do they go right back to their old ways, those familiar ways? We don’t ever find out, and that’s the point, really, that it’s not up to us, that people in this position, they have to help themselves, so the book ends, taking it out of our hands entirely, letting these characters’ lives live on in obscurity.

James’ writing is concise, not flashy, and rarely deviates from its set course — it lays out for us, almost diorama-like, the sets and characters, and doesn’t need this glitz and glamour that many young writers feel is necessary but, more often than not, isn’t. In fact, her terse style — which readily avoids fluttering up in the clouds with long, drawn out idioms and unnecessary dialog — strengthens the story: It’s these maddening, heart-wrenching characters, the snippets of human we see in them from time to time and their interactions, and the experiences they fall backwards into, that define the book, and with such color already present, anything more would take away and lessen the impact.

The Dead Beat truly offers a worm’s-eye-view of the world, through one deadbeat after another, and while there are plenty out there who have written or will continue to write about the dredge of society — those oft-overlooked “slackers” that represent, on a much larger scale, all of us in general (but, who are too afraid to let go, some might argue, as the dredge find so easy to do) — but James does it with such wit and style, with such a tight narrative that opens up just enough to let us in and poke around without overdoing it and creating pointless caricatures, one wonders how any could ever top her.

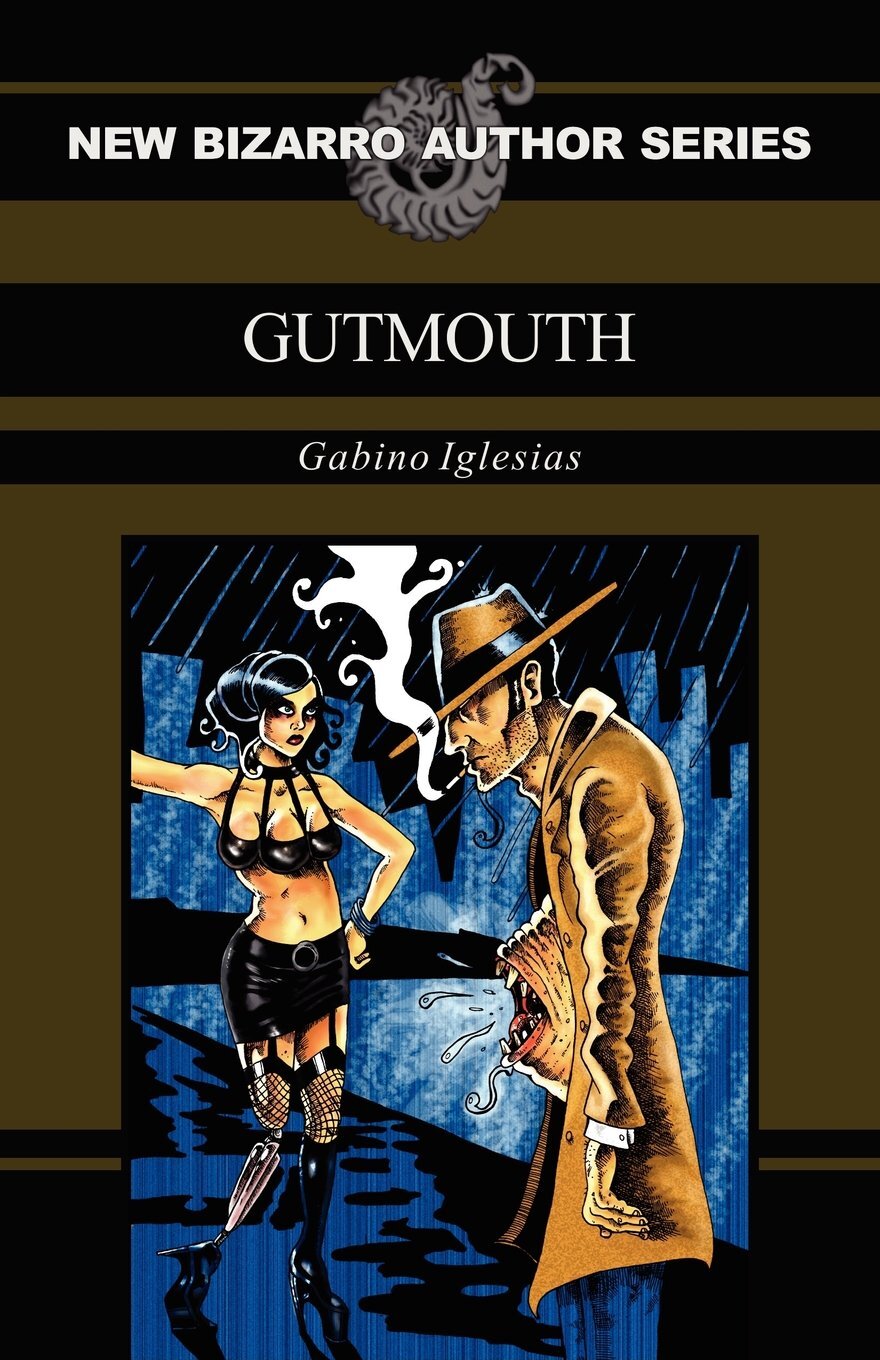

Defying Genre and Categorization As It Scoffs At Attempts At Civility: On Gabino Iglesias's Gutmouth

Considering how Iglesias ups the WTF factor (I’m sorry, but there’s no other word to describe it) with every chapter, I wouldn’t be surprised if in future works, he punts the bizarro to another stratosphere.

I haven’t read much bizarro fiction so I had no idea what to expect when I picked up Gutmouth by Gabino Iglesias. Expectations were shattered as the book was wilder than I could have imagined. Told in first-person, this is a visceral, intense read that grips you by the throat, defying genre and categorization just as much as it scoffs at any attempts at civility. There is a mouth called Philippe growing out of Dedmon’s stomach, a literal “gut mouth,” that poses an odd contrast with his fine tastes and British accent. As strange as that may seem, the world is even more twisted.

I looked up at the dark sky. Huge artificial asses hung from extension poles on top of every lamppost. The asses had been installed as method of crowd control when the New World transition began. The devices were designed to rain down acid diarrhea. Kind of like a postmodern version of a lachrymatory agent with an olfactory punch.

Olfactory punches abound and you will need to lift up your mental defenses as they will get bloodied and bruised by the barrage Iglesias volleys at readers. Dedmon was a repo man before MegaCorp took over the world and enlisted his skills to become a hunter. He tracks down “criminals” whose infractions against consumerism include not buying enough allotted products and “stubborn citizens who wanted to grow their own food.” Their punishment is inhumanly severe and even though MegaCorp “enjoyed using death row inmates as guinea pigs for new products,” there is an almost sociopathic apathy to Dedmon as he arrests the perpetrators without empathy. The combined Mr. Dedmon and Philippe are a misogynistic and misanthropic pair, brutes in every sense of the word. Satire and horror feed off each other, racing to chapter’s end with an absurdity that would make Kafka seem tame (and this despite the kleptomaniac roaches). Iglesias makes no attempt at being politically correct, but instead embraces the world with all its dark gory brutality. The implication is that since everything is commoditized, morality is tossed aside or at least distorted to an unrecognizable norm. Easily offended readers will find themselves turned off by some of the caustic exchanges as well as the expletives. But if you can see beyond it, then the societal criticisms and attitudes implicit in such a world provoke deeper questions. Take for example the medical technology that is so advanced, it allows for the reversal of pleasure and pain along with limb growth (spurred by salamandar DNA). The rampant genetic testing in part results in a pimple on Dedmon’s stomach that expands into the eponymous mouth. At the same time, it is also a parable for the modern man, torn into hundreds of different directions and driven by insatiable hunger and perpetual discontent. As though that weren’t bad enough, enter the love, or lust, of his life:

She wore a bologna bikini and a Viking hat. The thin slices of fake meat barely covered the nipples on each of her three breasts. Her skin glistened like a wet olive… By the time Marie was done jumping with her slimy stump buried deep inside the convulsing fat monster on the strength, I knew I had found the love of my life.

Dedmon’s conflict transfigures into a mutation of the traditional skew on dualism that is neither a Cartesian split, nor Hegelian dialectics, but instead, a mouth (Phillipe) that sticks his tongue inside Marie’s genitalia to arouse her, in turn arousing a vicious jealousy in the brain (Dedmon) that incites him to murder. In other words, the most fucked up love triangle I’ve read, seen, or heard to date. Shed the squid guards, the rat friend, the Genital Mutilation and Erotic Maiming Center, and a world torn apart by steroidal madness, and the bizarre is rendered in sympathetic flashes. Dedmon is just a poor bum in love with the wrong woman.

Without having breakfast, I got my clothes and shoes from the safe, dress and left. My feet carried me straight south to Shlicker Park. I sat on a beach, eyes still blurry with drink, heart broken and senses reeling. For the next few hours, I sat and watched the serpent-trees snag bloated pigeons in mid-air. The crunching of their tiny bones mixed with the frantic cooing from the survivors to create a perfect melody for a Saturday morning in the park.

Considering how Iglesias ups the WTF factor (I’m sorry, but there’s no other word to describe it) with every chapter, I wouldn’t be surprised if in future works, he punts the bizarro to another stratosphere. For now, I wonder if there is a secret mouth under Gabino Iglesias’s stomach that he is hiding from the rest of the world. I wonder what it will spew if given free rein. I hope it is not too hungry. I don’t want to be eaten.

He Is In Every Sense An Awful Man But He's Also Sympathetic

What’s immediately impressive about Big Ray is that it works exactly the way that memory works, at least some of the time. Daniel Todd Carrier’s father has, by the time the novel begins, died for some reason.

Michael Kimball’s Big Ray is the kind of book that will occupy your complete attention for at least fifteen minutes after Molly Gaudry hands you a copy to look through in her living room. You’ll be drinking tea and eating tea cookies, but you’ll have to stop drinking the tea so that you can turn the pages. You’ll keep eating the tea cookies, which you’ll shovel into your mouth faster and faster as you follow Kimball’s narrator’s brief flashes of sequential memory farther down their self-amending rabbit hole. You’ll be so into it, that you’ll be a little peeved when Molly takes the book away.

What’s immediately impressive about Big Ray is that it works exactly the way that memory works, at least some of the time. Daniel Todd Carrier’s father has, by the time the novel begins, died for some reason. His death could be attributed to any number of reasons, but those are hardly important. This isn’t a murder mystery or a medical exposé. This is a human novel about how a human son remembers his human father, who has recently become very humanly dead.

Kimball’s narrative unfolds through some of the most authentic, most honest prose that I’ve come across. When I was reading Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle, someone told me that he wrote a chapter a day. It made sense; this method explained how he never got long-winded, how one chapter broke so naturally into the next. Despite the impossibly apocalyptic Ice-Nine and the off-the-wall Bokononisms it seemed honest, even confessional. Kimball’s bite-sized chapter sections, the longest of which are two and three paragraphs, do a great deal to make Big Ray feel at least as immediate, at least as “true.”

The titular Big Ray is a big, disgusting, abusive, dead man. His presence looms larger than his 500-pound frame in this book, and it’s easy to write him off as a caricature at first glance, but it’s hard not to sympathize with him. We see him as a boy, as a high school student that looks like James Dean, and as a Private First Class in the Marines, but never as someone who sets out to do the wrong thing. He is in every sense an awful man but he’s also sympathetic, and he’s a figure who you’ll find yourself wanting to know by the time you’re through the first few chapters.

Our POV character is a grieving son, who is equally intriguing. He leads us through memories of the immediate fallout of his father having been found dead in his apartment, and alternates this narrative with one constructed of childhood memories. All of these are presented from the perspective of an adult mind rationalizing these experiences little-by-little.

Toward the middle of the novel, Daniel Todd Carrier has been relating his history of abuse at the impossibly fast hand of his father Big Ray, when he offers this tiny, reflective interruption: “Sometimes, I still get the urge to fight my father. If my father weren’t dead, I would kick his ass.” This kind of evaluation is tempered with flashes of memory that express another kind of sentiment entirely: “Sometimes, in the mornings before school, my father would look at the way I was dressed and say, ‘Looking sharp.’ That always made me feel really good.”

Big Ray is a novel full of terrifyingly dry wit, disgusting medical problems, beautiful sympathy, and honest-to-god people. It’s a page-turner in the best sense of the phrase, and you’ll have a damn good time reading it.