Horrocks Shows That Even In Bleakness And Heartbreak There Is Beauty

The astonishing thing about this book is that it is a debut collection by a young author as this is a collection of tremendous depth and breadth. There is an impressive range to these stories, limited only by Ms. Horrocks’s imagination, which is vast.

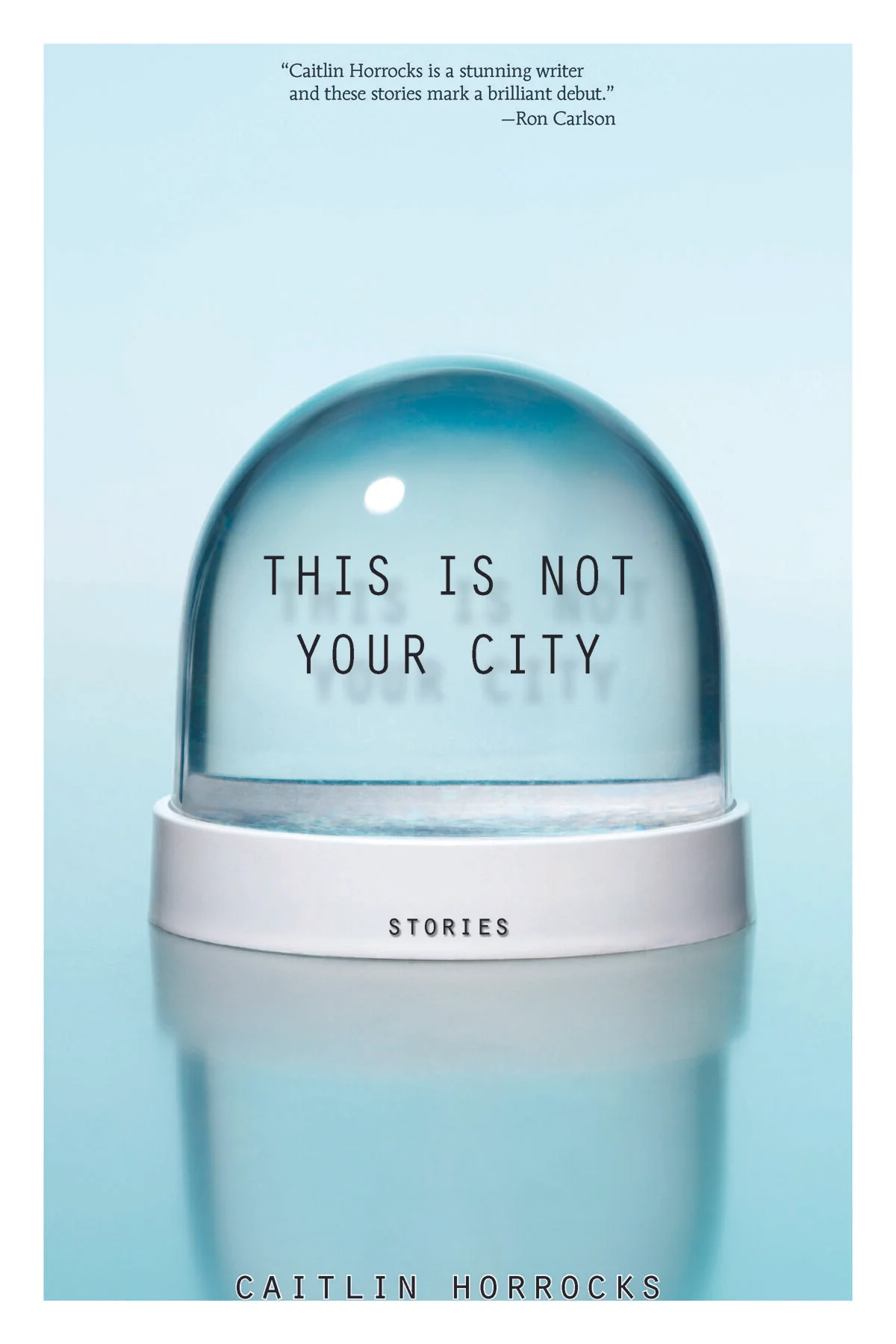

Caitlin Horrocks’s short story collection, This Is Not Your City, begins with this short, perfect sentence: “It is July and we are a miraculous age.” When I read it, I knew I would love the book, or at least I would love this first story. I felt I was listening to a strong, capable, and, most importantly, confident voice. The story is “Zolaria” and easily my favorite of the collection of eleven stories that make up the book.

The astonishing thing about this book is that it is a debut collection by a young author as this is a collection of tremendous depth and breadth. There is an impressive range to these stories, limited only by Ms. Horrocks’s imagination, which is vast. It is no surprise to learn from her bio, that she “lives in Michigan, by way of Ohio, Arizona, England, Finland and the Czech Republic.”

The stories are sharp, dark, inventive, and surprising. There is an emotional honesty to these stories and these characters, who are not victims nor martrys. I loved the moments of dark humor as well. In the story, “World Champion Cow of the Insane” (and if you think I’m not jealous of that title, you would be wrong), a young woman takes a part-time job teaching basic computer skills to the elderly and one of her students types into the subject line of an email: “Fucking Ignoramous = YOU.”

Horrocks shows that even in bleakness and heartbreak there is beauty. The prose is simple and uncluttered and powerful, as in this sentence, from the inventive story, “It Looks Like This”: “Sometimes while I’m making dinner or piecing a quilt or writing a paper, I just sit and know that Elsa thinks I’m a fish, and that things turn out all right for all the swimming things in the world.”

And this, from the dark and devastating story, “Steal Small”: “If this is what I get in the world, I’ll take it. Love and squalor, but mostly love.”

And here, from the unforgettable title story: “Nika is a practical child, and has never, as her mother once did secretly, rhymed storm clouds as dark as her soul, or a love that burned like fire.” Horrocks writes with such empathy and wisdom and such breadth of knowledge and experience, that one believes that, like the Iowa actuary in her story, “Embodied,” she has lived 127 lives.

Caitlin Horrocks is a talented, assured, and versatile writer and this is simply a stunning debut collection. I highly recommend this book and look forward to anything else that bears her name in the future.

"I’d want my sweat to show you what it means."

I cajoled my way into this write-up; my self-promotional skills are both effective and shameless. I wanted to write about Normally Special, the short story collection by xTx. When granted to me after much cajoling [re: harassment], I stalled, contemplating the task.

““I’d want my sweat to show you what it means. I would like the cramp of each of my muscles, and the withering of my fat, and the grind of my bones, and the blisters of sunburn to show you how I strived.””

I cajoled my way into this write-up; my self-promotional skills are both effective and shameless. I wanted to write about Normally Special, the short story collection by xTx. When granted to me after much cajoling [re: harassment], I stalled, contemplating the task. I dislike book reviews which attempt to pull money out of my wallet, or stuff the debit card back into my shirt pocket. Yes or no, withered thumb up or smooth, supple thumb down: Normally Special demands more.

When I corresponded with xTx about, among other things, Normally Special and its creation, our conversation turned sharp left into an alley, fell into a sinkhole and splashed into the blood and amniotic fluid and chlorine of literature, of memory: longhand for Lidia Yuknavitch’s The Chronology of Water. As writers, as people, we both loved the memoir -- love feels inadequate, here -- we honored the text and the subtext.

In talking about The Chronology of Water, I said to xTx, “I’m trying to find my own language here.” I said this as a man who hadn’t seen other men write about The Chronology of Water; I wanted to engage the book on my own terms, with my own words. No dice, so far. All I could utter was love as in “I loved it,” though meaning so much more: the interminable itch of wanting to be honest, even at the expense of clarity.

"I’d want my sweat to show you what it means."

Tiny Hardcore produces tiny books; Normally Special felt infinitesimal in my hand, as though it needed a blanket and a lullaby. Others have compared its diminutive size to the relative hulk-like musculature of the prose, the voices deployed, the text and the subtext. A fair comparison, I suppose, if not well-worn by now.

Let us, then, speak of women -- a specific type of woman, I mean: slow, quiet, internal burn; examining stones and the stray eyelashes dangling from her children’s cheek; brilliant, though hunched over by nameless weights or, god forbid, boulders engraved with the cursive of assailants. Stay with me.

"I would like [. . .] to show you how I strived."

There is punch, power, to the stories in Normally Special; they are, indeed, hulk-like, incredible. In our discussion [and in retrospect], I unfairly described the collection as, “a wink, I suppose, to the absurdity of everyday living and all that entails.” Unfair as in “dishonest” or, better yet, “clear.” I felt myself rustling up the usual rhetoric used to extoll the subtlety of a work, to say it is more than braun, to suggest it has soul.

I needed a better, dirtier language -- something messy and hacked to pieces -- for to say without saying, “Normally Special has soul” is to say the obvious. Moreover, there is nothing absurd about everyday life. Absurdity used in stories and essays and poems is mere salve to sooth the very-real scars literature, the good kind, reflects back to the reader.

What, then, is the wink? It was there, I swear it. xTx winked at me, I know it. If the overarching opinion of Normally Special is true, that it is terrifying and haunting, a clutch of the throat, then the fears and ghosts and disembodied hands reaching from beneath the subtext -- all of it -- is preceded by a wink, which is typically followed by a nod: the conflation of eye/head coordination says, “Maybe these women, these voices and characters, are your women, sir. How does that grab you?”

How, indeed.

Normally Special brought to mind, first, my wife, then my mother, grandmother, sister, nieces, aunts, cousins -- and certainly the trail of ex-lovers left behind me, scattered across the forgotten path like sun-bleached bones. In thinking about these women, I didn’t feel guilt -- rather, I felt compelled to consider them in whole, as individual universes made of matter so complex, applying my intellect to their makeup’s decoding seemed absurd.

What could I ever say about them? How could I ever devise or discover a language which serves as true communication of who they are in this world? How could I possibly use the word love -- past, present or future tense -- as commemoration of what they mean to me and, more importantly, what they mean to themselves? Perhaps that is the true nature of xTx’s wink, its subtext. “Shut up and read,” her wink said to me. “Shut up and listen. Just watch.”

"[ . . . ]the cramp of each of my muscles, and the withering of my fat, and the grind of my bones, and the blisters of sunburn [ . . . ]"

I am an unreliable narrator. Yes; brown thumb up; money pulled from wallet: buy and read Normally Special.

On xTx’s Normally Special

Some books are a surprise. Some books come at you like a bullet out of nowhere striking through some core part of your brain where you store vital information. Vital feelings. Normally Special by xTx is one such case. For whatever reason it took me a while to get sucked into the universe of xTx. This was before Normally Special.

Some books are a surprise. Some books come at you like a bullet out of nowhere striking through some core part of your brain where you store vital information. Vital feelings. Normally Special by xTx is one such case. For whatever reason it took me a while to get sucked into the universe of xTx. This was before Normally Special. This was before I bought Normally Special at AWP back in February. Before I read the whole book on the flight home to Oregon from D.C. And definitely before I spent weeks with Normally Special by my side when I was up late writing, as if it were a companion of sorts.

xTx has a way of twisting emotions to their breaking point, bending the reader to her will as she does so. And I was prepared for none of this. I don’t know why. Maybe because I’m inclined to be dubious to hype. Maybe because in so few instances is the hype deserved. But it’s not like I hadn’t read xTx’s work. I had. And it was good. But the difference is between seeing good paintings by an artist and then suddenly seeing them pull a Van Gogh out for you. Yes, Normally Special is a masterpiece, but the beauty of it is that its a masterpiece that only hints at the possibility, the potential, held in xTx’s words.

More than anything I would direct everyone who loves good writing, who loves a great short story, to read “The Mill Pond.” For my money it is one of the best short stories in the last year. At least. She breaks your heart, right from the opening line: “All of my tank tops are striped the wrong way for a girl my size.” Stories like “The Mill Pond” remind me in the best way of some of my favorite writers, and some of the best writers out there today, such as Bonnie Jo Campbell, whose short stories share the same devastation as “The Mill Pond.

I constantly find myself championing short stories to non-writers, who so often tell me that if they read at all that they prefer novels. Even with my my wife I have to sell the short story as a form. But it is because of writers like xTx that I love the short story so passionately. When I fell in love with writing it was due to Hemingway. When I have fallen back in love with writing continuously over the years it has been due to the short stories of people like Campbell, or Pete Fromm, Jack Driscoll, Raymond Carver, Flannery O’Connor. So many writers who exercise the greatest skill of precision a writer can, by encapsulating something meaningful into so few words. And xTx does that. And if there’s one thing I took away from Normally Special it is that xTx has the power within her to be a Bonnie Jo Campbell or even a Flannery O’Connor. The readers are just waiting for the rest of her words to show up. And I know they are coming. Until then read Normally Special again and again. Hold it close and feel what it’s trying to tell you.

Ethel Rohan On Reading

I read, and the tiny diamonds in my wedding band are thrown back on the page; one, two . . . eight tiny stones, tiny refractions of light.

"I read, and the tiny diamonds in my wedding band are thrown back on the page; one, two . . . eight tiny stones, tiny refractions of light. I move my hand so and the brilliant reflections vanish. Move my hand again and there they are back. There, gone. There, gone. Safely in and out.

"As a girl, I didn’t own jewelry, didn’t have anything but the words coming off the page, and me right there inside the story. Safely in and out. My mother called and called, chores and mending to be done, but she couldn’t get me out of the page, out of the words, out of the story. She raised the head of the sweeping brush and brought it down on my book, my lap, and first one knee, then the second knee. Her face the most terrible cover.

"Something died that day. Something I’ve yet to name. Not my love for books, for sweeping floors, for my mother. All that lives on. Invincible."

If You Don't Succeed, You Only Have Yourself to Blame: A Review of Will Boast's Power Ballads

Boast’s linked collection of stories entitled Power Ballads (which won the Iowa Short Fiction Award), introduces us to Tim who is also a damn good drummer. In “Dead Weight,” Tim replaces the overweight drummer in an up-and-coming band after the label decides he doesn’t meet their aesthetic requirements.

Will Boast’s story “Dead Weight” appeared in the most recent issue of Storyglossia. So what did I do after reading it (besides read it again)? Exactly what every person with a Facebook account does these days: I began stalking him. First I sent him a message to tell him how much I loved his story. This was accompanied by a “friend request.” Then I listened to his band. Here’s something else I discovered: Will Boast is a damn good drummer.

Boast’s linked collection of stories entitled Power Ballads (which won the Iowa Short Fiction Award), introduces us to Tim who is also a damn good drummer. In “Dead Weight,” Tim replaces the overweight drummer in an up-and-coming band after the label decides he doesn’t meet their aesthetic requirements. In other stories, we see young Tim playing tuba in a polka band and later gigging with a rock band past its expiration date. But a degree in music theory isn’t required here. The real music is in the interplay between the characters.

What’s fascinating (and what makes me maddeningly jealous) is how Boast talks about music without talking about music. Sure, there’s mention of the hip blogs Pitchfork and Stereogum, as well as ruminations on the vibrant Chicago music scene. In each story, the characters are musicians at varying stages of their careers or the wives and girlfriends that come second to the music. But the trick is this: the book isn’t about any of that. These are people struggling to find their identity.

For Tim, who is the link between most of these stories, finding himself is hard when he’s constantly filling in for someone else. He’s the guy they call when a drummer drops out or isn’t good enough for the big time. If the money’s right, he will play with over-the-hill metal bands or quiet singer-songwriters. Tim finds fault with his father who is constantly starting over, finding new ways to make money and new places to live. He resents his father for not keeping a home for him to return to after his mother died. It’s not until the end that he sees the irony of his scorn, that he too is constantly reinventing himself for each new band and project. Just like his father, he can’t settle down.

That sense of identity, of finding your purpose, all hinges on the amount of fame you hope to achieve. This is summed up brilliantly by Sue, the wife of a non-stop touring musician in the story “Sidemen” and is something that I think every artist understands:

“Thirty years ago, people bragged about their sister or uncle or brother-in-law being personal secretary, gardener, caddy, you name it, to such-and-such city alderman or some bigwig down at Montgomery Ward. Now everyone wants to be lauded on their own merits, adored if possible. Does getting by no longer constitute a life? Thirty years ago, you were proud to be a janitor, to scrub toilets in a good building, work for a good company. Now you despise yourself for missing the chance at something better, something that might have gotten you featured in a magazine. Fame is never out of reach; you just didn’t grab it when you could have.”

And that’s the heart of the struggle. If you don’t succeed, you only have yourself to blame. When Tim’s father gets hurt at his current job loading food into a freezer, Tim leaves Chicago to visit him in the hospital. They tell his father that he’ll never have to work again, and Tim knows that will be the end of him. These odd jobs define him. Before heading off to tour Europe with a jazz band, Tim goes to his father’s apartment to get him some clothes for his hospital stay, and he finds a shrine his father has erected in his honor. His father has pictures of Tim setting up his first drum set, watching Elvin Jones in concert and a drawing he made as a teenager of a stage with all the spotlights pointing at him. In the most poignant moment of the entire collection, he finally makes an admission:

“I felt embarrassed and shy to see that here, in this obscure corner of nowhere, I’d already made it.”

Read this book as soon as you can.

And Then I Read Normally Special & Knew I Feel Fucked Being A Girl Or The Legend of xTx

Good news is if you’re a girl and have read Normally Special, you know weakness isn’t romantic. Men don’t save us. Art is an offensive play. Female empowerment exists. But it’s fragile. I’m tired. Is this the handbook for girls like these, torn knees, slanted eyes, Kool-Aid in dirty jars, and secrets? Maybe this is a precautionary tale. Maybe you’re fucked being a girl.

“I’m a mess. Dirty, like he said. I’m feeling every bit of being a woman. I resent the weakness of my sex.”

—from Normally Special by xTx

Where would you like to begin? With the good news or bad?

Bad news is more girls have read Twilight than Normally Special.

Good news is if you’re a girl and have read Normally Special, you know weakness isn’t romantic. Men don’t save us. Art is an offensive play. Female empowerment exists. But it’s fragile. I’m tired. Is this the handbook for girls like these, torn knees, slanted eyes, Kool-Aid in dirty jars, and secrets? Maybe this is a precautionary tale. Maybe you’re fucked being a girl.

Where would you like to start? With the writer or the book?

Normally Special, available for $9.99 from Tiny Hardcore Press, is smaller than my hand, which might disappoint if size matters, if you’re accustomed to the weight of a man, I mean a book, upon you. Don’t worry. You’ll feel the weight of this book.

Ninety-four pages. Twenty-three stories. Many of them a page or two long.

Still you could tie this book to your ankle and walk into a river and drown.

Good-bye, Virginia Woolf.

In writing this review, I spent a great deal of time thinking about Normally Special, re-reading the stories, and quizzing the author by email. Around all this, I lost my job, boss laid me off, and so my situation as a single mother with a mortgage, a car payment, and bills-bills-bills became precarious, or in spirit of Normally Special, more precarious. Because ladies life according to Normally Special is this: womanhood is weakness, degradation, terror, exhaustion.

There is a rampage. There is a tornado of anger. Men will come for us, sometimes as children, and they will show us no mercy, not relent. In “There Was No Mother In That House,” pages sixty-four and sixty-five of Normally Special, a girl realizes her act of rebellion, knocking over her brothers’ fort, is as bright and short-lived as a sparkler.

Her brothers finally find her in a tool shed and beat her senseless.

There you go. Snuffed out.

The cover photo for Normally Special provides a brilliant, if not beguiling, hint to what we’re in for. The picture by Robb Todd depicts a street scene, trash bags nearly off camera, a bike, a view into two shop windows and maybe the reflection of Christmas lights. But here’s what’s striking: a baby girl in a yellow dress framed by an enormous door looking off camera in contrast to a man in a red shirt stepping into the street and so closest to camera and therefore the largest image in the picture. The impression is, he’s charging into the frame. Impression is the girl is stunned. At least bewildered. The photo renders her diminutive.

And even if she grew six feet tall and sprouted fangs, the girl remains a timid monster.

You should be glad there isn’t a part of my brain that clicks, breaks, and changes Wolfman-style into something that can break skin razor sharp into every piece of every part of you. Something that needs to feed on the fear screaming in your pupils of your green fucking eyes, bites your sweet throat warmest of veins screaming for my warmest of mouths, stubble a delicious obstacle to the smoothness of my tongue. You will never need a single silver bullet for me. You will not need a stake made of wood. You will not need holy water or a Jesus cross or torches or pitchforks or any other sort of protective weapon made for monsters such as me. I’m the most timid of monsters. They have removed me from my position within their ranks citing words such as fail, coward, reject, weakling, useless, stupid, worthless, dumbass.

Where would you like to start? With a whisper or a scream?

So many of the women in Normally Special never scream, either they can’t or won’t.

In “The Importance of Folding Towels,” a woman crosses her arms over her chest. That’s it; that’s defiance. Yes, her scream. Another woman smashes fireflies in place of screaming. And still another in “She Who Subjected the Sun” sits on a chair trying not to choke to death while a man mouth fucks her with his hand and another woman is murdered beside them.

We never see the murdered woman. The narrator never looks. She imagines the tracks she makes in wake of what’s left of the dead woman behind her on the floor. Later, she stares into the sun without blinking, which will fry your pupils, leave you blind, but then tries to convince us she’s won. I’m not sure this is triumph, except when I ask the writer about female empowerment in the context of her book she provides a list of examples.

The woman in "The Duty Mouths Bring" distracts Juan with a smile and slows his box making.

The mother in "Standoff" is empowered in the end, the author says, because she gives up, which is sad, but then it’s something she has power over. Well. Yes. Each of us has the power to give up.

Another woman in the book fantasizes control over a boy in “Good Boy, Fritos.”

I feel I would have the emotional advantage over Fritos in that he would need me more than I would need him. This would be a first for me and I would feel a sick power in this feeling. I know if I asked Fritos to hurt himself because it would make me smile that he probably would.

Yes, Fritos like the corn chips. The story begins with the narrator eating them. Fritos is young and Hispanic and “almost chubby” and the narrator orders him to jab himself in the stomach with a drink sword, thirty-three times. The end is ambiguous. Either Fritos continues jabbing himself in the stomach or he turns the sword on the woman’s naked tit with it and stabs her.

Female empowerment in Normally Special isn’t Spice Girls, isn’t Angelina Jolie kicking ass in Salt, isn’t women who attend college or own businesses or run for President. Sure, a few times female empowerment appears in a familiar guise, a woman turns a man on sexually or preys on a boy, but usually it’s less familiar. More dire. Like if you live through this, you’re empowered. Or maybe it’s more twisted than that, far more uncomfortable.

For instance, if your father fucked you when you were a child, and now as a woman you’re able to masturbate then come while fantasizing about your father as he was from your childhood days, is that empowerment or symptomatic of trauma, psychosis? Both?

Normally Special asks this question with “I Love My Dad. My Dad Loves Me.” I wanted to know the genesis of the story, but the author refused to go into it. She did say, “Incest is a horrible thing. It’s disgusting. It’s probably one of the hugest betrayals that can be perpetrated on another. It fascinates me. It’s probably ugly to say that but I’m hiding behind my fake name so it makes it easier.”

Where would you like to start? With who the writer is or isn’t?

xTx isn’t a feminist. She isn’t an anti-feminist either.

“I hope I’m not a let down to my sex for saying so.”

She’s a girl of undetermined age and race. Her name is a pseudonym.

Her name started out as a joke.

“xTx is an alphabetical version of a dick-and-balls,” said the author. “It’s a shield.”

The discussion could go two ways from here. One, the author’s name represents a dick-and-balls, which is ironic in light of her subject matter.

Like, being female sucks.

So invent a name that’s not female. That represents the oppressor.

But here’s another way the discussion could go.

“Maybe I ought to have a dick, on accounta how I seem to approach certain sexual things,” said xTx. Meaning masturbation and porn.

When xTx first began publishing online as a blogger, she didn’t want anyone to know who she was, which isn’t uncommon in the blogosphere, especially among women who write about human sexuality or confront taboo topics. This is twofold is you’re married, threefold if you’re a mother. Plenty of my female peers write erotica or sexual memoir using pen names because they don’t want the world-at-large to burn them at the stake or ostracize their children.

Lest they be cast out as the spawn of whores.

I don’t think xTx is married. I don’t think she has children, although two of the stories in Normally Special are narrated by mothers. In both these stories, “An Unsteady Place” and “Standoff,” the mothers come unglued, unravel, give up.

“Mothers are not given permission to be breakable,” xTx told me. “Yet they are probably the most breakable things in the world.”

Yeah, but what about the children? They could end up living an xTx story like the girl in “There Was No Mother In That House,” or another, “The Mill Pond” in which a mother worries more about her daughter’s weight than well-being, which leaves the girl at the mercy of a child molester.

“I can only speak from my experience of being a girl and a woman,” said xTx, “but I think we have a lot of stuff happen to us because of our sex. I just think that’s how it’s always been and how it always will be and I like to ‘look at it’ by writing about it. I wish I could protect all the little girls in the world so they don’t have to write stories like mine.”

Perhaps the characters xTx breathes fire and life into are more witch than princess, more perverse than pristine, heroic in ways we don’t expect or readily celebrate, yet isn’t that what both literature and pop culture need, a hotshot of anti-heroine so we all OD, in order to eradicate sexism and prejudice?

Jerry Stahl once described JT Leroy as “Flannery O’Conner tied to the bed and plied with angel dust.” xTx is a young Joyce Carol Oates on meth careening down the middle of the highway in a red Fiat without the headlights on. Frantically, bravely. Miranda Lambert on the radio. “Your fist is big. But my gun is bigger.” Her light is the moon. Every time a woman writes, she commits a political act.

Sometimes she writes a love letter to her gender.

A part of me inside a part of you . . . a part of you inside a part of me . . . Those times you put down the razor, that was me forcing your hand. Those moments where you told them no, that was me giving you strength. Each time I stepped back from the ledge, that was you pulling me back. Whenever I kept walking instead of falling down, that was you holding me up. We were saving each other then so we could save each other now and so we do. And so we are.

Blake Butler said if he knew xTx’s true identity he’d file a restraining order against her, which is either sexist or isn’t. xTx says the majority of her audience is male. At least men review her book more often, and more men frequent her blog. What the hell does that mean?

The author has no explanation.

More girls have a copy of Twilight than Normally Special.

Q&A with xTx

xTx is a shortened form of a longer name I used to blog under. It is the alphabetic version of a dick and balls. It is the stupidest pseudonym ever. It is a fortunate mistake. It is a shield.

Where did the name xTx come from?

It is a shortened form of a longer name I used to blog under. It is the alphabetic version of a dick and balls. It is the stupidest pseudonym ever. It is a fortunate mistake. It is a shield.

Why do you call your pen name a "fortunate mistake?" This intrigues me. After all, your name is a "dick-and-balls.”

My pen name is "fortunate" because it seems to get attention/stand out and it's a "mistake" because I never expected it to become "something" and now it's more well-known than my real name is or will ever be (maybe) as it pertains to the online lit scene.

The "cock and balls" likeness was something I just recently realized it sort of resembles -- in my twisted mind, anyway. Maybe I subconsciously equate being powerful/having a protective shield with the strength of a male, i.e. the cock and balls imagery. Maybe not. I dunno.

I'd like to know more about you. How old you are. What you look like. If you're a mom. Were you sexually abused a child? What else do you do, aside from writing? Are you in school?

Those are the lots of things that lots of people want to know about me. If you want to know what I look like there are a handful of people that met me at AWP who can do some artist renderings. For the other things, well, when I finally meet you for burritos and margaritas at that place you mentioned, I will tell you all about them.

Have you discovered a particular freedom in anonymity?

Of course. I don’t (often) have to worry about what others think. I don’t have to censor myself. My tits out, paper bag over my head, sitting on a sidewalk.

Honestly, if I stepped out from behind the shield I would feel vulnerable as hell. I mean, sometimes I already do. This year I met a bunch of "online people" at AWP and kept thinking they were thinking, "She's the one that writes all that fucked up shit all the time," and then I think maybe they are judging me. I don't know. Either which way, it's nobody’s fault but my own.

But maybe eventually I would feel empowered, like, finally own my shit and be proud of it and be like, "YUP, THIS IS ME TOO!" Maybe that would be a huge relief. Maybe that would be a Sybil-like, multiple personality integration party in my soul. Double-lives are hard.

Do you think writing anonymously is one way to keep art and the artist separate? Should art always speak for itself regardless of the artist, like who he or she is and what personal stake he or she has in the material?

I do think the art should speak for itself. When I read a story or love a painting that is all there is. I wonder about the creator, but, really, the creator is separate. Sort of how a baby is born; first one with the mother and then separate into the world. They are always together, but yet, they are individuals. It’s interesting to know the parents, to get some background or perspective on the child, but in the end, the child is its own thing. I hope that makes sense.

Name three writers who've lent you courage as a writer.

Roxane Gay, Ethel Rohan, and Lidia Yuknavitch just because of the very personal and intense subject matter they write about USING THEIR OWN NAMES. Reading them makes me feel ashamed of how I hide. Their courage gives me courage. One day I hope I will act on that courage.

Do you consider yourself a feminist? An anti-feminist? What?

I’ve never classified myself as much of anything. I don’t think I’m either of those things. I hope I’m not a let down to my sex for saying so. Please let the record reflect that I’m a huge fan of boobs and vaginas and the owners thereof.

If you described Normally Special in one sentence, compound but not complex, how would you describe it?

A tiny, hardcore collection of brutal, ugly, and beautiful.

"Normally Special" is an oxymoron, isn't it? Talk to me about that.

Normally Special is taken from the last story in the book which is a story about a woman obsessed with a man but who is trying to convince him that her obsession is a safe one, but in the convincing she is making it obviously clear that it is not safe at all. The full sentence is, “I did not Google Earth you, so none of these thoughts took place and you can go on speaking to your neighbors who think you are only normally special.” I love the contradictory nature of the term, “normally special” because how can one be both?

On the cover for Normally Special we see a man first and then in the distance a small girl. The photo seems to represent a power dynamic going on in the book, between men and women. Talk about that power dynamic and why it became so central to your stories.

I love the cover shot. I can’t get enough of this photo which is why I chose it. (“Little Girl in Yellow in SoHo” taken by my friend, Robb Todd.) The tininess of the girl, the way she is framed in that huge doorway making her appear even more tiny and vulnerable, the faceless man in the foreground wearing a color that makes bulls charge, the contrast between them that evokes a subtle feeling of danger, the fear of the obvious vulnerability of the little girl. How I worry about her. This cover does sort of capture a lot of the themes of Normally Special.

I can only speak from my experience of being a girl and a woman, but I think I am drawn to the men/woman power dynamic because of how much shit women are subjected to along the path of their lives by boys/men. I think we have a lot of stuff happen to us because of our sex. I just think that’s how it’s always been and how it always will be and I like to “look at it” by writing about it. I wish I could protect all the little girls in the world so they don’t have to write stories like mine.

But this power dynamic in the stories. "The Duty Mouths Bring," for instance, has a great deal of this going on, a competition between the sexes. When I read your stories I feel like being a woman is a slippery slope, fucking precarious. What about this attracts you as an artist?

I guess I am drawn to writing about the woman as a victim in a lot of different ways; a victim of circumstance, a victim of a man, of herself, etc. I’m not sure if this is considered a “power dynamic” or if it’s just showing how someone might struggle when faced with dealing with different life events/experiences. One woman is forced by her husband to fold towels “properly,” one woman is abused by an “uncle,” one woman gets almost taken advantage of in a bar bathroom, one woman struggles to feed her son, one young girl gets abused by her brothers; I like to explore the ugly most of the time. It just always seems to be man vs. woman in most of the cases.

You tackle a taboo subject in Normally Special, incest. The story "I Love My Dad. My Dad Loves Me" opens with, "It is difficult to masturbate about your father, but not impossible, as it turns out," and walks a thin line between titillating and horrifying readers. Talk to me about the genesis of this story.

Incest is a horrible thing. It’s disgusting. It’s probably one of the hugest betrayals that can be perpetrated on another. It fascinates me. It’s probably ugly to say that but I am hiding behind my fake name so it makes it easier. The inner workings of a parent who uses their child as a thing for sex is crazy fucked up shit. I don’t understand it. I think that’s why I have written about incest, in various forms, from time to time. Especially the aftermath. How does a child “go on” from something like that? How does that affect them later in life? The confusion of loving a dad despite what you know he did was wrong and that you might even hate him for it but the child’s voice still whispering to you, “but he’s my daddy” and “but I love my daddy, my daddy loves me.” How the desire for a father’s love can make a little girl/woman’s voice of denial so loud that she chooses to believe nothing ever happened, even when she goes looking for it and maybe even thinks she finds it. It’s easier to cope with what we tell ourselves.

I won’t talk about the genesis of this story.

What are your thoughts on "Writers should write what they know?" Does an artist have to be or come from a place in order to write about it? Or are you able to relate to characters unlike yourself because you're able to identify with like emotional experiences?

I guess we are all a bit limited to the things we know but I don’t know if that means we don’t write about the things we don’t. Maybe they won’t be written as well as if we did, and if a writer wants to take that chance, go for it. I stay within whatever I feel comfortable writing about. If it begins to extend into unfamiliar territory, and I feel the story needs it, I’ll do my best to learn as much as I can in order for it to be as “true” as it can be.

Dads show up a lot in your stories, don’t they?

Well, now that you mention it, I guess (they do.) I probably will never show my dad this book.

I've been rereading stories and decided my favorite is "An Unsteady Place." Where did it come from? When did you write it? What was going on at the time?

I wrote this story while in a beachside vacation rental house on the Oregon coast. I wrote the first section longhand, in a notebook, sitting in a sunroom on the top floor. Man, I loved that sunroom! I could’ve written there for a month! The first paragraph of that story is basically what I wrote in my notebook, no revisions. The décor of that house really was ridiculous. You couldn’t get away from the seaside imagery. It was literally everywhere. The ridiculousness made a feeling in me that had to get out which is my “writing feeling” and so that’s where I started; the décor. When I got to the part about all of the little instructions everywhere -- notes on how to use the microwave, the oven, where to put the trash, etc. -- and I wrote the line, “There is no way you can make a mistake here.” I think that set me on the path of, “What IF you could make a mistake here? What would that look like?” and that’s when I think I knew the story would be a dark one. I love the contrast of what is supposed to be this happy, family getaway turning into one woman’s unraveling. I love how the rest of the family just goes on like nothing is happening and still expecting her to be a mother, a wife. As I said before, so much is put upon that dual role that people who depend on that dual role forget the person is breakable, can be broken. And, quite often, the mother/wife feels obligated to her duty so much so that she sacrifices herself in the process.

Were you and I discussing "unreliable narrators" on Twitter? The narrator of "An Unsteady Place" is certainly unreliable because she's going crazy. Did you consider allowing readers to see around her as a way to reveal the validity of her perspective?

It wasn’t me you discussed that with on Twitter. I think if I let readers “see around her” to really know if she was going crazy or not, the story wouldn’t be the way it is. It would be an entirely different story. I like the not knowing. I like how it isn’t grounded all the way. I think we all feel a bit unsteady in our lives even when beautiful things are all around us. Sometimes we are living her without the imagery. I wanted the reader to be able to feel that/relate to that.

Ernest Hemingway once said the best writing happens when emotions run high. Talk to me about tapping high emotion. Do you find power as an artist in anger? Is it a traditionally impolite thing for female artist to do, get pissed off?

Emotion is imperative for writing. Dead cannot write exciting. I frequently have to put myself into an emotional place in order to get what I need to get for certain stories. If I am losing a vibe in a story, I have to stop, sit, and put myself in the proper feeling and write from there. I have to feel what the narrator feels so I can tell the reader properly. I like showing my readers my guts. I want them inside my skin.

Anger is good. Anger is impolite if you are a woman, which is stupid. Which is why I would write about something like that. I like making people look at things they don’t want to look at. Car crash, eye surgery, aborted fetus.

A couple stories in Normally Special come across as letters, don’t they? Talk to me about how this worked for you as an artist, writing stories addressed to a "you." How do you think they work on readers? For instance, does it create intimacy between writer/reader?

Ha, I do that all the time -- writing to a “you.” Anytime you see a story I’ve written addressed to a “you” know that it was an easy story for me to write. I have a lot of “yous” in the world who I (insert strong emotion/feeling here) and those pieces usually start with one of those feelings and move on from there. I’ve never thought of them as letters, but I guess maybe they are. I could probably print them out, fold them three times, stick them in envelopes and mail them to the people who inspired them. Some would be happy to receive them, some would be horrified and some would be scared. A lot of times when I write them, I am glad I use “you” because I know a lot of people will think, “Me?” and I like having thin walls between us -- me and the reader. I want people to want to be the “you” in my stories. I usually want to be the “you” in other people’s stories. I like the intimacy of it. I wish I could do one on one readings with each of my readers in dark rooms with thighs touching, both of us with nervous hearts.

Who did you picture as your audience while writing Normally Special?

Honestly, I am a pleaser. I have a huge problem with wanting people to like me. When Roxane (Gay) asked me to do this book, all I cared about was impressing her. The mantra of, “I hope she likes this,” was always humming away, always in the back of my mind pushing me to do my best. I didn’t want to disappoint her. If she was happy with my stories, then I knew everyone else would be. I don’t write with an audience in mind, unless, of course, I’ve been asked to do so. I just write. The audience will come.