The Grandfather Is the One Who Said the Thing About the Water Buffalo on the Back of the Book

For me, one of the highlights of the pre-Highland Ice Arena parts of T&T, where we spend a lot of time in the narrator’s house, is meeting and getting to spend a lot of time with the Grandfather. Many readers I’ve talked to have cited the Grandfather as one of their favorite parts of the book.

For me, one of the highlights of the pre-Highland Ice Arena parts of T&T, where we spend a lot of time in the narrator's house, is meeting and getting to spend a lot of time with the Grandfather. Many readers I've talked to have cited the Grandfather as one of their favorite parts of the book. Whimsical, manic, and perhaps the one character who thoroughly eludes the narrator's cloak of perception, in part because we suspect it's the grandfather who taught that cloak. The boyfriends' personalities are subsumed by the narrator's perception of them in an interesting way, but the Grandfather is Grandfather. He bakes blueberry pies, he encourages anarchism, he doesn't mess around.

In his review of Today & Tomorrow, J.A. Tyler suggests we should pair the narrator's Bill Murray obsession with Grandfather. Which Bill Murray is Grandfather, though? I think it's a cross between The Life Aquatic Bill Murray and a grandfatherly version of Bill Murray from the bowling movie where Bill Murray's toupee is in his face a lot. Not Broken Flowers Bill Murray. Plus Grandfather doesn't have that hipster eff-it-all suave one tends to associate with Bill. He's like if Doc Brown drove his time machine into all of Bill Murray's roles and started making a mess.

When I was thinking about what exciting pull quote to put on the back of the book, I emailed Ofelia and asked her what her favorite Grandfather monologues were. Even though the book is clearly about the trip through the narrator's head, somehow the Grandfather is the most quotable. Maybe from the way he talks and embellishes we can see where the narrator gets "it," but what Grandfather ends up saying is miles away from everybody else, including the narrator, and those miles seem headed for the moon. Ofelia said her favorite grandfather monologues were as follows:

1. Power windows (beginning of ch. 47)

“Use your power-windows,” Grandfather said. “Make the buzzing sound.” He was laughing. “Buzz,” he said. “Buzz buzz buzz.”

2. Death (beginning of ch. 18)

"It’s like this. Everything that’s alive dies and so it’s no big deal to kill a thing because it’s natural. People don’t kill things directly and so think killing’s evil. It’s not. Every person should kill something—start in elementary school. If I were President, I’d mandate that each kindergartner slaughter a live chicken the first day of school, then every year thereafter, first day of school, students would slaughter a larger animal. Rabbits, cats, mountain-goats, all the way up to senior year and a healthy goddamn bovine. This would take some planning and maybe you just have one fucking cow per home-room. I don’t know, but America would be a better place if there was more killing and a more comprehensive understanding of death.”

3. Pies (beginning of ch. 35)

“Pie was invented by a Roman or something, Cato the Elder. Write that down.” Grandfather was laughing. “Cato found that the best way to pacify Roman populations was to drug them with pies. His pie was more of a tart with honey and goat-cheese, probably—there are several surviving recipes, but who’s to say which is the right one—anyway, he added, I don’t know, hemlock or something, strychnine, tricked the would-be rioters, the probable evil-doers, into eating these pie-tart-things with hemlock, had to be hemlock because that was how Romans liked to poison people, and every day Cato’d send out a cart for the dead, poisoned, would-be rioters, and sometimes two carts, horse-drawn carts, or donkeys maybe, and he’d have his men gather the bodies and dump them in the river, or if the weather was inclement, pile them up and burn them, in a big pyre, ridding Rome of evil-doers and simultaneously warming nearby homes. He was very innovative.”

So yep, the Grandfather is one of my favorite parts of the book. I believe that movement through a book, what we read for, is something that each book reinvents for itself. The question isn't always "what's gonna happen next?" One of the biggest pleasures I take in T&T is reading to see what the Grandfather will say next. He's hilarious and tender.

What do you guys think? Do you have a favorite kooky old person in your life? Do you want to float any theories about T&T's Grandfather? Do you want to post a URL of your favorite Bill Murray picture?

Story Focus: "More Than Gone"

{I will open with an anecdote.} Yesterday my good friend Carter had a birthday party in a park a few blocks from my house. The children laughed in the splash park. The adults behaved like adults, sitting at the picnic tables talking about their adult things.

{I will open with an anecdote.}

Yesterday my good friend Carter had a birthday party in a park a few blocks from my house. The children laughed in the splash park. The adults behaved like adults, sitting at the picnic tables talking about their adult things. There was punch, hot dogs, chips, brownies, chocolate cake. All what you'd expect from a birthday gathering in a park. This is a boring story, really.

Don't get me wrong. It was a good time, but it makes for no good story.

{I will segue into a discussion about the story I am writing about.}

Rohan's "More Than Gone," which you can read in full and in slightly different form at Halfway Down the Stairs if you don't have Cut Through the Bone yet, follows home the widowed grandma after the birthday of her granddaughter, "her first public gathering since Albert's funeral." She carries a balloon from the party, imagining it as a friend, telling it all the happy stories of her late husband, taking care to note how passersby smile at her, "indulgently" as she puts it.

I think it's important to note a difference here between the texts. In Cut Through the Bone, Rohan leaves this here, let's us infer what the passersby are indulging--that this old lady is talking to a balloon as she walks through the park. What would you think? Of course you'd think it. Let's not try to convince ourselves that we're any better here.

In the version of this story at Halfway Down the Stairs, Rohan goes on, let's us know exactly what it is they are thinking: senile. And pushes another step with a line that doesn't appear in the book, "There are times she wants to be senile."

{I will interject some discussion about current cultural topics along with some pop culture discussion.}

There exists now a drug to help you forget. Two of them, actually, both in testing.

Immediately I think of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. I think of running. I don't know why I think of running. There is that scene, maybe, in Eternal Sunshine, where they are running through the snow. I love that scene, but it makes me feel so cold. It makes me want to throw snow in your face.

I can't understand anyone who doesn't want to remember what it's like to feel that kind of powdery cold love against their face.

I'm terrified of forgetting. The other day, we talked about how lies become a part of our personal narratives. I wonder how I will respond to the forgetting. I wonder if I'll simply make up my own stories to replace those lost to memory, if I'll construct an elaborate fiction of my life, and thinking of that, it's almost comforting--a daily fugue, a daily recreation.

{I will go back to the personal.}

My grandmother wakes every morning forgetting that my grandfather passed away. She thinks he is already awake, down at breakfast maybe, or in the lounge watching a fishing show on TV. I can understand that kind of forgetting, I guess.

I still remember the first time Grandma ever forgot my name. I was slicing apples on Thanksgiving, helping in the kitchen as I've done for years. I've always been handy with a knife and a spatula. Grandma was standing there, talking to my step-mother and me, and I kept hearing her say, "Clint. Clint." Eyes on my knife, I had no idea she was talking to me until she tapped me on the shoulder. She looked into my face, and laughed in her soft old lady laugh, and said, "Oh you're not Clint. Oh. What's your name again?"

I've never asked my dad if he knows who Clint might be.

{I will ask you a series of questions in hopes you will leave answers in the comments section.}

Are you terrified of forgetting? What do you want to forget? What don't you want to forget? Do you take photos or write down things you are afraid to forget, or do you live by the phrase, "Why write down what one is to remember forever?" Do you remember that time we walked through the snow, that we found the space beneath the brush of the fallen pine tree where the city seemed to disappear, where we made believe we were rabbits hiding in the underbrush, careful of the foxes and the wolves and hunters?

Story Focus: "The Big Top"

I used to tell a lie. It wasn’t a particularly harmful lie. It wasn’t to cover up another lie, or something that I thought would hurt someone or implicate me in some crime or misadventure. It was simply a lie about why I am afraid of clowns.

I used to tell a lie. It wasn't a particularly harmful lie. It wasn't to cover up another lie, or something that I thought would hurt someone or implicate me in some crime or misadventure. It was simply a lie about why I am afraid of clowns. It went like this:

When I was 5 or 6, my mom took my brother and me to the circus, despite my insistence on not going. The circus was a dirty and sad place to me, and I wanted nothing of it. Naturally, a clown, seeing a stubborn and cranky kid, thought he would try to creep a smile on my face. He jumped up to me, his movements comically exaggerated. He crouched low, getting in my face, asking stupid clown questions like, "Why so glum, chum?" in a voice like Disney's Goofy. Without thinking, I cocked my arm and loaded it right into the clown's big, bright nose, which let out a screeching honk-honk as the clown toppled to his ass, his scowl made terrifyingly preposterous with his clown makeup.

It's not even that great of a story. I can usually make it work when hammed up on beer and silly, but seeing it on paper reveals its lack luster. I don't even know why I started telling that story. I'm not even afraid of clowns.

I don't trust people who say they're afraid of clowns. Clowns are one of those things I feel 90% of people say they're afraid of, but maybe only 20% of people really are, if that. Unnerved seems a better, more honest term for the feeling I get from clowns, but it's funnier to be afraid of them, to exaggerate the feeling to fear, the irony being that a clown is the very epitome of an exaggeration for comic affect. So to say you're afraid of clowns when what you really mean is unnerved is to act a clown yourself.

The other irony that exists is that there really aren't any clowns in Rohan's story, "The Big Top," which unfortunately doesn't appear online for me to link you to, so I'll just excerpt the intro here:

I spotted the poster in the supermarket window, a large glossy sheet with a bright splash of words and colorful snapshots of the clowns, trapeze artists, and the Big Top. That evening over dinner, I suggested to my husband we'd go.

He sprinkled too much parmesan over his spaghetti. "What would bring us to the circus?"

"What wouldn't?"

He let the obvious hang in the silence.

We'd never managed to have children.

They appear on a poster in the first sentence, but not after that. Reading is funny, man. There is so much loaded into this story, so much that is not about the lies we invent for ourselves to tell between pints and shots, but my mind latched on to this idea as soon as I read the first sentence, it steel-gripped the theme and wouldn't let me read the story in any other way. In 5 years, I'll read this story again and respond to it in a completely different way. Perhaps Britt and I will have decided, however unlikely, that we want kids. Perhaps we'll have been having a hard time of it, something or other in one of us not functioning properly despite all the wanting.

This is how I respond to reading. I rarely read with what one might call a "critical eye," at least beyond whether I enjoy what I'm reading. I don't get much satisfaction looking at a piece of writing and asking, "What does it mean?" as though it were some riddle to be unlocked. I was happy to leave that behind when I graduated from Ball State.

Asking "What does it mean?" is a much different question than "What does it mean to me?" If I was still at BSU responding to this story for my comp class, I would write about the longing of wanting a child and not having one. I would write about the themes apparent, what the color blue means searching for why Ethel chose that color for the monkey, possibly about the crisp sparse language.

But that's not what it means to me. To me, it means lying, it means finding a void to explain a feeling in my life and creating a simple silly fiction to explain it. It means telling that fiction over and over throughout my life until it becomes a part of my story. It means my friends who might have heard this story reading this blog post and what their reactions might be.

What does this story mean to you? How do you respond to reading--more analytically or more personally responsive? Have I told you this story as though it were true? Are you afraid of clowns?

Deep Body Yawns

Do we keep ourselves surrounded by the structures we grew up with? How do we ever find room to be alone with our families? With their memories? With our obligations to the people we love?

In the early chapters of T&T, as we joyride along with our narrator and her boyfriends, slashing dresses into triangles and harassing AM/PM clerks, bickering with Aaron (“You can be my assistant, you know, assist me.”) and Erik/Todd (“Have you ever been to Wal-Mart? Do you know how big it is, how full? I organized fucking everything.”), we eventually end up at a house, which the narrator promises they’re going to rob (“Home-invasion”) but which turns out to be her old house where her grandparents live. We also learn, through the narrator’s wandering memories, about her sisters and her family. For today’s blog post, I want to talk about families. Here’s a passage from the end of Chapter 7 where the narrator remembers about an old family trip:

I think about the rusty minivan, about backseats and Anastasia and Merna and the seatbelts and crisscrossing the seatbelts and the knees, exposed knees in the summer, bumping together, and the wind from the window-crack and the very warm very yellow sunlight through the window and the relaxing just before with sleepy eyes and deep body-yawns in late afternoon. We drove through the Rockies to Montana when I was ten or twelve. Mother at the wheel, Father sleeping quietly in the front passenger-seat. Merna read to Anastasia from teen-magazines—manicures, dating, how to tease your bangs, how to be beautiful. I let my head flop to the side and sat very still and made my eyes flutter then close and stopped my breathing and waited for my sisters to shake me.

“Don’t,” Anastasia said.

“She’s dead.” Merna pushed me. “She’s really dead now. People just die like that sometimes. The speed’s too much for their brains.” I didn’t react, but remained very still, allowing Merna’s pushes to move me slackly until I flopped over Anastasia’s lap.

“See, she’s dead,” Merna said. “Anastasia, you killed her.”

“Stop,” Anastasia said.

Later we pulled into a gas-station and I hid behind the backseat, beneath our backpacks and tents and travel gear. I made myself still and quiet and relaxed and smelled the tent and sleeping bags, the cooler, the stuffed backpacks that smelled of mold and mildew and dirt. I wanted then to smell that way, to lie quietly in the unmoving wetness of those smells. This is probably what death smells like, I thought. Nobody’ll ever find me here, I thought. I waited for Merna to uncover me, for Mother or Father to search me out, to remove carefully the sleeping bags, tents, backpacks, to stack them outside in the parking-lot, and to find me curled up and sleepy and cold. For Anastasia to say quietly, “Stop,” and to cry then in Merna’s lap. I could hug them, could sprawl my body over their bodies, could wait passively to be moved from one somewhere to another. The tents did not move. The sleeping bags remained still. I woke there later, beneath the tent, beneath the sleeping bags, the backpacks. I was cold and wet, hearing only the rough vibration of the van over concrete.

In a family (even a small family) it’s hard to find the space to be alone, and especially harder to find a place to nestle into where we can be still. This passage reminds me of two things, and I’m not sure how related they are, but I think they relate in some weird way to do with a relationship to giving ourselves up, giving ourselves over: 1) When I was very young, my family would sit out in the living-room while my mother read to all of us. Often I would pretend to fall asleep so my father could carry me to bed. He knew I was pretending, and he made a big production of the carrying in a fun way. 2) A friend of mine organizes his bookshelves by alphabet and color, and it’s hypnotizing how perfect it is. It makes me either want to slide myself in the right slot or knock everything down, mess it all up.

Chapters in T&T rollick along with their chaos, but they often end on achingly beautiful depictions of precarious setups or feelings, the idea of trying to capture things where they landed. I’m interested in what we might have to say about the way Hunt ends chapters, and I’m interested in what we might have to say about families. Because I think these too are related in some weird way I can’t quite put my finger on. T&T’s narrator seems to cocoon herself between her two boyfriends the way she used to cocoon herself between her two sisters, and she often finds herself trying and failing to linger at moments where she can surrender to what she’s surrounded by: curled up, sleepy, waiting “passively to be moved from one somewhere to another.” Do we keep ourselves surrounded by the structures we grew up with? How do we ever find room to be alone with our families? With their memories? With our obligations to the people we love?

The Metaphor Is Closer Than You Think

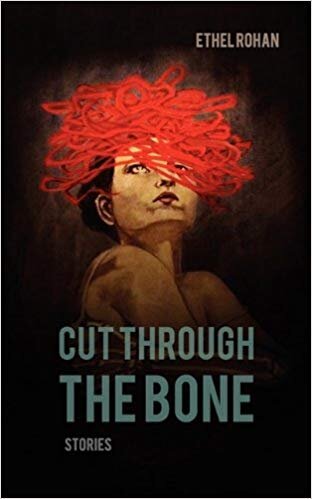

Throughout Cut Through the Bone, Rohan identifies the many ways in which her characters’ loss and struggle might manifest physically in their worlds.

I have a painting in my apartment. It looks like this:

I like this painting for several reasons: its simple lines and muted colors. How the only, even vaguely, bright shade in the entire work is the red of the woman’s small, down-turned mouth. It is a sardonic, sad red—not bold, not celebratory.

Mostly, though, it’s the woman’s eyes that get me—eyes not unlike those in other Modigliani paintings, but wider—as deep and dark as two caves, so black they look dead. Or they make the woman look like she herself is dead. This is what haunts me about this painting. I can’t decide if she is metaphorically dead (emotionally dead, dying, stricken, etc.) or actually dead. A ghost.

I feel this is the painting Ethel Rohan would paint if she could. This dark image of this woman. It’s not just that, like the lines in the painting, Rohan’s writing is clean—though it is most certainly that. There is nothing unneeded in her prose, no word that is not doing something, if not two or three somethings. Tight. But it is more that the metaphor in this painting—showing a woman as actually dead to indicate an emotional/metaphorical death—is one that Rohan herself would use.

In the short story “Makeover,” the protagonist, a wife and mother, has a wild woman inside of her chest who wants her to wear tight, racy clothing and sing and dance. The woman gets excited when the protagonist satisfies her “wild” desires: “While she sang, the woman in her chest danced, spun and spun.” The metaphor is clearly wrought: Sometimes women (and men) feel as though they have a different version of themselves inside themselves that is trying to get out. It is a version that one’s family and friends might not, and probably do not, appreciate, as this is not the mother, wife, friend, etc., with whom they’re familiar. In “Makeover,” the woman’s family protests until she acquiesces, returning to her normal behavior, leaving the woman inside of her chest clawing and shrieking, unhappy.

Another character, the protagonist of “Shatter,” lives a broken life. She has a shitty job, a mediocre marriage, probably a drinking problem, and a sister with whom she doesn’t have a close relationship. Throughout this two-page story, nearly everything around this woman literally breaks—glass jars and the grocery bags she packs full at work. These objects break and others constantly threaten to break. What in a longer, more diffuse story might serve as a motif becomes the story’s central action and metaphor. In this way, Rohan makes the elements of her fiction work harder, accomplish more, than they might in another author’s hands. Her images nearly always work double—serving literal and symbolic purposes, pointing towards the tangible and intangible.

In the titular and final story of the collection, a masseuse gives a massage to a man whose leg was amputated after a motorcycle accident. This physical loss can be seen as visually representing the absence of the masseuse’s son. The last time she touched her son, “held him for any length,” was in some distant past. Throughout Cut Through the Bone, Rohan identifies the many ways in which her characters’ loss and struggle might manifest physically in their worlds. In fact, this last story feels like a metaphor of the collection itself. Like the woman who massages the air where the man’s lower leg used to be, throughout the book Rohan works in spaces defined by their emptiness, what was once there but is no longer. All those people and things that leave indelible, palpable marks in their absence.

Like that painting on the wall? In a month, a man will come and take it, because it is his. He’ll take some other things that belong to him too: a sleeping bag and tent, a 1977 edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, and a small wooden rack that holds magazines. I want to keep the painting, all this stuff, but none of it is mine. I feel that if this were a Rohan story, these objects would take on a life of their own—the woman in the painting would sprout legs, the books would flap their pages like wings. If this were a Rohan story, these objects would slowly disappear, piece by piece, long before anyone comes to take them.

Stride Mechanics and Broken Toys

Thanks everybody for your thoughtful discussion about violence! As we continue to dig into Today & Tomorrow and start to meet some of the novel’s key players — Erik/Todd the Wal-Mart cashier, Aaron the eerie new guy, Merna, the memory of Anastasia — I’d like to call to your attention a couple new interviews with Ofelia that’ve gone up in the last couple days.

Thanks everybody for your thoughtful discussion about violence! As we continue to dig into Today & Tomorrow and start to meet some of the novel's key players -- Erik/Todd the Wal-Mart cashier, Aaron the eerie new guy, Merna, the memory of Anastasia -- I'd like to call to your attention a couple new interviews with Ofelia that've gone up in the last couple days.

Over at the literary magazine Monkeybicycle, J. A. Tyler talks to Ofelia about Bill Murray, violence, and coming of age. Here's something interesting Ofelia says about the novel's relationship to growing up:

I was 28 years old when I started T&T, and I’m now 32 years old. I might be regressing. I graduated from college four years late. And there’s something odd about approaching and entering your 30s. When my mother was 30 she had three children, was immersed in the work/eat/sleep routine. The language of violence is interesting and it surrounds us (television, movies, newspapers). “I want to stab that mofo in the face,” is funny. I remember a former coworker saying that about a demanding customer, while miming a stabbing motion. Also, as I wrote and edited T&T I remember being very concerned/interested in the separation of body and thought, the separation of any body part from any other, and the compartmentalization of the mind. Violence, real and imagined, seemed one way to write about this. Bodies are so mechanical. Parts fail and are replaced. I like to run long trail races occasionally and the racers become very focused on ‘refueling’ and ‘stride mechanics’ and the possible failure of their parts (a foot, a tendon, the iliotibial band). Perhaps ‘coming of age’ is a step toward subjective understanding of one's own body, and move toward greater mental compartmentalization. One learns to become many people as needed, for work, friends, lovers, partners, the internet, to subsume/suppress the parts that do and don’t fit current roles.

* * *

Then, over at the lit blog We Who Are About to Die, Noah Cicero talks to Ofelia about influences, the process of writing, concrete truth, and consumerism:

NC: Do you believe that consumerist culture makes people into non-humans? I get that from the book, everyone is turned into a non-human, they have been turned into something, what, no one can really say, but the primitive instincts are gone from the humans in your book

OH: Consumerist culture makes me feel robotic and alien. I have trouble existing in large masses of people, at shopping malls, Wal-Mart, Target -- I become nervous, awkward, clumsy. Television commercials make me bitter and sarcastic. I feel weird when media outlets discuss professional athletes, actresses, and politicians as ‘commodities.’ I find it strange that the polite language for couples to refer to one another is ‘my partner.’ Our day to day language is overrun by business metaphors. ‘Business’ is the standard for excellence in most of American life. Speed and efficiency or something. Lack of waste or excess (not that ‘business’ generally lives up to these standards). I sometimes feel like people often rely on objects outside of themselves to accomplish goals, and are never deterred when those objects don’t perform as expected. I have nightmares of broken toys from my early childhood, how I felt when the toys disappointed me.

* * *

Both these interviews are very insightful, and I suggest checking both of them out in full. Meanwhile, what do you think of Ofelia's answers? Do we become more compartmentalized as we age? Do television commercials make you feel sarcastic? Do you find your everyday language overrun by business metaphors? Do you have nightmares of broken toys from your early childhood?

And -- taking a cue from Chris's discussion of Cut Through the Bone -- are there things you find yourself wanting to ask Ofelia that no one's asked yet?

Story Focus: "How to Kill"

First off, I wanted to thank everyone who participated in the conversation on Monday. It seems talking about unbalance between the respect given to male and female writers strikes a chord.

First off, I wanted to thank everyone who participated in the conversation on Monday. It seems talking about unbalance between the respect given to male and female writers strikes a chord. Who'd've thought women had opinions about things?!

At any rate, I had an awesome time hearing from everyone, and if you're joining us now and missed Monday's post and subsequent comment conversation, feel free to check it out. And you're still welcome to leave your thoughts in the comments section, of course. The conversation is still rolling on.

Today, I want to focus on a reading of a specific story from Cut Through the Bone, one that continues to chew at me since I first read it a couple months ago, and now, mining the book and my brain for things to write about here, continues to gnaw and gnaw. "How to Kill" (which you can read in full at Hobart) is a story about a relationship trying to make it in the wake of an abortion. We're never told whether at the time of the abortion the girl was okay with it and is only just now regretting it, but I get the feeling that's not the case--that she wanted the baby, but he didn't.

Ethel's language in this story is masterful in its subtle layers. With each read of "How to Kill" I find another phrase that hints at the hurt and anger that roils beneath the skin of this nameless narrator. The first line, how careful she is not to break the yolk, only becomes truly apparent once the conceit of the story is revealed. Later in the story, how Matt pushes away his plate, "the left overs looking violated," and I can just see the yolk, now broken and running, perhaps smeared around the plate with toast, a couple corners of crust resting next to the remains of the ketchup, deep red. I don't think I need to explain the underlying metaphor there.

I don't want to belabor the gender-card here, but I can't help thinking of Kyle Winkler's comment from Monday, "My masculinity has been severely tweezed, judiciously slit-up, and decidedly analyzed thoroughly, and better in some instances, by women more than men," in relation to my own thoughts and response to this story.

It's easy to read this story, think simply, "That dude's a dick," and move right along to the next story. And you'd be right. And you'd be wrong. But, I think that dude is hurting--in the only way he knows how: tough silence.

Regardless of his relief after the abortion, he still obviously cared about the girl: went with her to the clinic, reassured her, helped her home and in to bed where he laid with her. You see, I knew a guy once who was simply a dick. I tried and still try to extend some ounce of grace to that guy, but I can't. Unlike Matt in the story, this guy did none of those things. This guy didn't do much more than offer to pay for half the procedure. We were out for beers when he told me all this. I'd known him a few months, seemed like an okay dude, at least a dude I could laugh with and drink some beers, feel a little bit like I had a pal in a new city. After this night, I never drank with him again.

Years ago, I thought I was going to marry a girl, and then I didn't think I was going to. A couple weeks after we talked about this, she called again. She said, "I'm late." I said, "I'm terrified." She said, "Me, too." And we did what we thought was right. We gave it another chance under the banner of that common terror.

Once the decision was made, we breathed easier, laughed more. We were both able to convince ourselves that my initial leaving was frozen feet, that maybe this would work. We welcomed the term "expecting" into our lives with talk of baby names and what books I would read to our kid before bed. And just as our terror left, her blood came.

We laid in bed for days, my warm hands resting on her belly, a warming pad. Her body was wracked with cramps and sobbing. I brought food and drink to the bedroom, but we hardly ate any of it. I got a call from my boss, fired for a couple of no-call, no-shows. I wasn't about to leave.

Of course I left, a few months later. I grew quiet and tired, sullen. Spent hours at the computer writing. Started stepping out for band practice before she got home so I could spend more time alone, less time dodging the conversations about our devastation, until one day, I packed my sedan with what little I cared to own, and left a note.

Reading "How to Kill," I hated Matt, and hated seeing myself in him. But also, I recognized myself just as easily in the narrator, who seemed to have no choice in the matter of the abortion. This girl and I, we didn't have any choice. Her body made the choice for us, and all we were left with was the question, "What would have been so terrible about us having the baby?"

I wonder sometimes if men shy away from this fiction because of the way it exposes us to these quiet desperations that we'd rather ignore, because it's easier for to externalize our conflicts with old men and the sea and fist fights and shooting lions and drinking beer in our front lawns. Like Kyle said, often times it's female narratives that most deeply expose who we are as men, perhaps because they are not us, but observers, able to render us more true than we allow ourselves due to our egos or ingrained perceptions of how we are supposed to act as men. I don't know.

All I know is I'm glad for stories like "How to Kill," stories that render me true, allow me to see both sides of myself. It's not that reading this story has changed my life, nor do I think it'll change yours. But it does what all good stories do--provides a mirror through which you can examine who you have been and who you are, and decide who you want to be.