They Obliterate Us with their Aerobatics of Language and Rhythm

Bradley and Tomaloff mesmerize us with their transmission of cadence and meter. It’s music, improvisation with the volume turned all the way up, quadraphonic sound and we’re standing trying to hold ourselves together in the midst of it.

My brother used to build these rockets we’d launch when we were kids that would blast up into the atmosphere forever. We searched and searched to find out if its explosive magic would ever manifest in the vacant lot where we stood staring up into the sky. We were sure it had found its way to another planet, but then somehow this white, phallic-shaped thing would plummet back down into our world again, intact but with burn marks, changed. That’s what happens when you pack together the right ingredients. You come up with an implosion of the spontaneously combustible kind. Ryan W. Bradley and David Tomaloff are that kind of ammunition. They obliterate us with their aerobatics of language and rhythm that bring us back to ourselves. We can imagine that we have escaped, but forget that you are a mammal and you had better watch your back.

the afternoon is a tourist a noose

with its arms spread out like a clock

when it is Sunday afternoon I make believe.

play the part of the father left rotting in the den

a half empty glass for the fifth time today

the dampened spark of ice cubes failing to ignite

this is a time capsule raised from barren soil

the aging bomb shelter of the nuclear family —

Bradley and Tomaloff mesmerize us with their transmission of cadence and meter. It’s music, improvisation with the volume turned all the way up, quadraphonic sound and we’re standing trying to hold ourselves together in the midst of it.

where then is the skin

we peeled from one another,

the would be bone-clothes

in which we earned our scars?

what we struggled so long to support,

to cut our teeth on failure

building a better ribcage

to house a more broken heart.

You Are Jaguar is two hands shaking in the woods, two voices wandering in our heads stretching the territory we didn’t know we spanned, a dueling navigation of subterfuge that surfaces and exposes itself within every stanza.

draining like suburban gutters

into the careful concealment

of flowerbeds below . . .

& with it go my teeth

cut for hurricanes,

holding fast to the edges,

of the photos we’ve become:

This is a collection that blasts through us with the violation of our truths. There is nowhere to go but inward. We must own the beauty and debauchery of the animals that we are.

. . . if you are the mandible, I am

the mouth swallowed whole I am

the glint in the city’s eye recapturing

a sense of how to crave the jungle.

Bradley and Tomaloff are packing in the ammo and setting off the fuse. Get a copy of You Are Jaguar and find out where you land; scorched, yet transformed.

More Opposite than Black and White: A Review of Mary Leader's Beyond the Fire

Mary Leader has long been known as an innovator in her own work, using both aleatoric methods and traditional forms. Forms as machines, in a way, that make demands on their content. Her two previous books (1997’s Red Signature and The Penultimate Suitor, published in 2001) share this fascination with merging the traditional and experimental aspects of poetry.

When I moved to my first apartment in Indianapolis, my possessions were scarce: a bed, a couch, and two Virgin Mary nightlights. By chance, the only bulbs I had for them were blue and red — the remnants of an after-Christmas decorations sale. I joked with visiting friends, dubbing them Good Mary and Evil Mary. We talked about how the arrangement — one for the kitchen, one for the bath — was strangely apt; how we mortals live, doomed to oscillate between needs, walking constantly toward one, then the other. It wasn’t until much later that I became aware of the work of yet another Mary, who has just come out with her exciting third collection of poems, Beyond the Fire. It is in this book that I see this same sort of alternating movement.

Mary Leader has long been known as an innovator in her own work, using both aleatoric methods and traditional forms. Forms as machines, in a way, that make demands on their content. Her two previous books (1997’s Red Signature and The Penultimate Suitor, published in 2001) share this fascination with merging the traditional and experimental aspects of poetry. Starting with the experimental element in this book is: “They Vibrate,” what appears at first to be a concrete poem, an uneasy square of text for the eyes to enjoy at the expense of the voice. It’s a poem which ends up being, on closer investigation, the key to the entire book. It consists of lines of super- and sub-scripted opposites that vary over the course of the poem, the complementary colors red and blue, for example, which Leader sees as more opposite than black and white:

redblueredblueredblauredblaurotblaurotblaurotblaurotblaurotblauredbluere

These opposites morph into others: whore / virgin, mortal / venial, Mars / Venus. Rose / Iris turns to Eros / Ire. What, at first blush, looks to be a block of wavering lines of text becomes instead the juxtaposition of opposites ranging from gender to particle theory, and it succeeds with wonderful economy. The book, as a whole, also oscillates between these. Pentacostal Christians and Jews. Age and youth. A child’s still life and the seminal works of Kandinsky. Poems even bisect themselves, such as with “Among Things Held at Arm’s Length,” divided into poems for Mother and Father. The patterns beget new ones. Writing becomes weaving. In “They Vibrate,” the block of text suggests fabric, and in “Persistence of Empire in the Dream of the Pastoral,” we find the weaver. The speaker finds nine trees and moves between them: “and around / their trunks one by one I move, a spool — // Red grosgrain—in my right hand, and in my wake — / Blue — a nice loose shank of rope narrow of / Gauge.”

It is easy for me to get hung up in the details of structure and how these various motifs set about these vibrations, but it is plain to see that these were not Leader’s only concerns. The language is incisive and exact. The poems are not only small machines, they are machines that do something. Take, for example, “Folio,” one of the major poems in this collection, which incorporates the elements just mentioned:

Consider the distinctions among aether and air and oxygen within a hundred breaths of death // I mean, normally, the outer sphere of heavenly edge whether imaginary in myth or actual in imagery from the Hubble Telescope (see, “aether”), and the grand earthly surrounding supply (see, “air”), are lovely—taken for granted—containing and expanding as they do—but when it comes down to it, the true necessity to keep life from stopping is the O (see, “oxygen”) // Molecule, element, fundament

The work also unforgettably portrays the scene of her mother’s death:

Her body is at issue: flesh, bone, ignored hair / [ . . . ] / Her teeth, loose pebbles, studs in brackish water, saliva pooled dark as tobacco

It is here that we see as it was suggested in “They Vibrate,” that the poem catches things mid-oscillation; a family’s argument surrounding the speaker’s not coming to her mother until the last moment fades in comparison to larger issues: “Within eleven years, I will forgive Armand, whose own skull, in her / nineties, under skin so fair it belongs only to those born with red hair, supplies her cheekbone-knobs, which mine match // And of self-forgiveness, that part of the Janus figure stays inchoate.”

It is with an intricate movement of thread against thread that the pattern on the face of a textile materializes, and so it is with Leader’s book, a wide-ranging and remarkably cohesive collection that comes highly recommended.

Trying to Survive the Day-in-day-out of Adult Life

Consider the Lobster is the first book I’ve read by David Foster Wallace. I’ve been interested in him since reading the commencement speech to Kenyon College’s Class of ’05, in which he suggests that the value of a liberal arts education is not that it teaches you how to think, but that it teaches you what to think about.

Consider the Lobster is the first book I’ve read by David Foster Wallace. I’ve been interested in him since reading the commencement speech to Kenyon College’s Class of ’05, in which he suggests that the value of a liberal arts education is not that it teaches you how to think, but that it teaches you what to think about. Awareness of one’s thoughts, he says, is the means to the end of compassion, which “involves attention and awareness and discipline and being able truly to care about other people and to sacrifice for them over and over in myriad petty, unsexy ways every day.” It takes real effort, he argues, to snap out of our default setting of seeing ourselves as the center of everything, to adjust our thinking. “This,” he continues, “is the freedom of a real education, of learning how to be well-adjusted. You get to consciously decide what has meaning and what doesn’t. You get to decide what to worship.” And we all worship something—if not a god or gods, then money, or power, or our bodies. (Here he makes an compelling argument for religion when he suggests that theistic figures are the only things we can worship that won’t “eat [us] alive.”) Be aware of what you worship, what you grant value to, what motivates you. He concludes by saying that paying attention to our thoughts is immensely demanding to do while trying to survive the day-in-day-out of adult life, and is truly the work of a lifetime.

Consider the Lobster is a very varied collection, and none of these essays truly fit a type, but to generalize for now, the collection contains a piece of lit crit (“Some Remarks on Kafka’s Funniness…”); a personal narrative of 9/11 (“The View from Mrs. Thompson’s”); two pieces that see Wallace play journalist at huge-in-certain-circles type events (“Big Red Son” [The Adult Video News Awards], and the title piece [the Maine Lobster Festival]); two behind-the-scenes looks at rather niche industries (“Host” [conservative talk radio], and “Up, Simba” [political campaigning]); and four book reviews whose subjects range from Tracy Austin’s autobiography to A Dictionary of Modern American Usage (“How Tracy Austin Broke my Heart,” “Joseph Frank’s Dostoevsky,” “Authority and American Usage,” and “Certainly the End of Something or Other…”). The ideas articulated in Wallace’s Keyon speech in some way inform every essay in this collection, and I can say without reservation that every single essay is terrific. I feel ridiculous even pointing this out, but it’s all true: his gift for analysis of just about anything was surreal, and he was incredibly deft at writing with clarity about even the most abstract ideas. But most importantly, I think, he had the ability to ask the right questions without ever making an argument for his answer over yours; like in the Kenyon speech, he just wants you to be aware, to choose consciously.

Maybe this is best exemplified in the title essay, where he wraps up by encouraging readers to ask themselves a host of questions about eating meat:

“Do you think about the (possible) moral status and (probable) suffering of the animals involved? If you do, what ethical convictions have you worked out that permit you not just to eat but to savor and enjoy flesh-based viands? If, on the other hand, you’ll have no truck with confusions of convictions [. . .] what makes it feel truly okay to just dismiss the whole thing out of hand? That is, is your refusal to think about any of this the product of actual thought, or is it just that you don’t want to think about it? And if the latter, then why not? Do you ever think, even idly, about the possible reasons for your reluctance to think about it? I am not trying to bait anyone here — I’m genuinely curious.”

See what I mean? He is not asking you to stop eating meat, but asking you to have some awareness about the thinking that underlies that decision. Consider.

Wallace had convictions, of course; but he was incredibly skilled at presenting his ideas without arguing for them. He seemed to approach everything with what he describes in “Authority and American Usage” as a Democratic Spirit, which “combines rigor and humility, i.e., passionate conviction plus a sedulous respect for the convictions of others.” For example: Wallace explains that on the topic of abortion, his stance is both pro-life and pro-choice. He is pro-life because he believes that if something might be a human being, “it’s better not to kill it.” On the other hand, he is pro-choice because given the “irresolvable doubt” of the situation, the Democratic Spirit requires him to respect your opinions and the decisions you make as a result of them.

He is never, ever, not once, dogmatic. In “Host,” Wallace talks with conservative radio show host John Zeigler, who is obsessed with the O.J. Simpson murder trial. John Zeigler, who is sure that he “know[s] more about the case than anyone not directly involved,” and even more sure that O.J. is guilty. John Zeigler, who after being fired from his radio show for making what he describes as “an incredibly tame joke about O.J.’s lack of innocence” blames it on the station’s “cav[ing] in to Political Correctness.” Zeigler’s worst offense? For DFW, it’s his refusal to acknowledge that he could be wrong—about O.J., about anything; it’s his absolutely certainty about everything: “. . .one can almost feel it: what a bleak and merciless world this host lives in—believes, nay, knows for an absolute fact he lives in.” Wallace’s response: “I’ll take doubt.”

He maintains the Democratic Spirit even while writing a totally scathing review of John Updike’s Toward the End of Time. It’s surprising that Wallace would write a piece verging on a takedown, except that his main problem with both Updike and his protagonist is that they lack awareness, lack the consciousness of thought that he implores the Keyon Class of ’05 to have. Discussing Updike’s protagonist’s confusion at his relentless unhappiness, Wallace writes: “It never once occurs to him, though, that the reason he’s so unhappy is that he’s an asshole.” And Updike does nothing, Wallace suggests, to separate himself from his protagonist, to ironize him; he is guilty of the same lack of awareness.

And this, I believe, is what made Wallace such a very special writer. All the things that separate him stylistically are reflections of his commitment to seeing things from as many angles as possible. The footnotes? On the Charlie Rose show in 1996, Wallace linked them to a desire to create a fractured text, to disrupt linearity. This ambition is inextricable from his ambition to be conscious of thought — the enemy is always narrow-mindedness. The sprawling, multi-clause sentences, chock full of words you might never again see elsewhere? He needs each and every one of those obscure words if he’s going to give proper voice to his ideas and those of others; lest something be misunderstood, he needs each of those clauses to articulate his ideas — which he believes in passionately — in all of their complexities, and to articulate the convictions of others, for which he has nothing but the greatest respect. The humor? It’s mostly observational, the result of simply being open to seeing.

It is through this approach that Wallace achieves the trait he praises in Dostoevsky: he, as a deeply moral writer, is not moralistic. Wallace leaves you, his reader, thinking, pondering new questions and, most importantly, pondering your own pondering. And after reading this collection, you’ll be more open than you’ve ever been to the idea that maybe you don’t know.

Grand Animated Formations in the Sky: A Review of Adam Novy's The Avian Gospels

We’re dealing today with a story of a long-standing dictatorship, a city in flames, people streaming into the streets to rise up against their oppressive government, and that government’s attempts to crush the rebellion. And I’m not talking about Cairo. The Avian Gospels is a hell of a good dystopian novel that may seem eerily prescient regarding recent events, but resonates even more so in light of past forays into the Middle East in the last decade. It’s a strange, surreal, and fascinating ride.

We’re dealing today with a story of a long-standing dictatorship, a city in flames, people streaming into the streets to rise up against their oppressive government, and that government’s attempts to crush the rebellion. And I’m not talking about Cairo. The Avian Gospels is a hell of a good dystopian novel that may seem eerily prescient regarding recent events, but resonates even more so in light of past forays into the Middle East in the last decade. It’s a strange, surreal, and fascinating ride.

A father and son (Swedes — or are they Gypsies?) live in an unnamed city in some unnamed country that borders Oklahoma. A war with Turkey does not unseat a Stalin-like Judge from power. His thugs, called RedBlacks, share their leader’s love of torture to extract information. Gypsies (or are they Norwegians?) are heavily oppressed and live in a network of tunnels under the city.

Ever since the war, a plague of birds has settled on this bleak urban landscape, and the avian congestion is especially thick on the grounds of the Judge’s enormous and echo-filled mansion. The father and son have the unusual and spectacular inborn ability to make the birds do their will: the son organizes them by color to form grand animated formations in the sky.

No one knows why the birds are there or what they mean. Are they the return of those who died in the war? Are they a plague brought down upon an unjust land in need of regime change? “We suspected,” the unnamed narrator says, “that we deserved the birds.” Add to this surreal cocktail the action-filled plot of revolutionaries and arson, all packaged in two beautiful Bible-like volumes, complete with rounded corners and gilt page ends. It all, strange enough to say, works together wonderfully.

The events of the last ten years — not to mention the events of the last month — make uneasy reverberations in this novel: a green zone, spider holes, “bring it on,” a city filled with murals of the ruling family on the walls, coffins buoyed up by protesting crowds, the political need to use fear to inspire coherence to what is going on — cast their shadow over this novel. While not directly referring to any particular war, terrorist event, or military action, the novel gives a disturbing sense of all of these, a deftly-unsettling story that is a sublimation of the chaotic handling of the policy of regime change and terrorism-management.

That certainly is a lot to chew on, but the power of the prose moves you through, shifting from the people at the forefront of the gathering resistance movement to those tightly holding the reins of a land rolling full-speed off a cliff. On both sides it’s a brutal tale of mislaid and misused power. Novy’s writing is deliberate, controlled, and the narrator, who tells this story long after these events took place, keeps a certain remove from the characters’ points of view, keeping us ever in sight of the greater landscape — a bird’s-eye view — that shows the overarching results of their actions.

Real vs. Irreal: Mining a Thoughtspace Threading out Inner Realities

The last two books I read were The Great Lover by Michael Cisco and The Sensualist by Daniel Torday. They were widely different, the first being 300+ pages of dark fantasy and the latter a slim novella set in the real world. It was a coincidence that I happened to read them successively, and I think if I hadn’t read both, if I’d only ever read either one, I might not have posed this quintessential question I’d like to pose to you.

Prologue

The last two books I read were The Great Lover by Michael Cisco and The Sensualist by Daniel Torday. They were widely different, the first being 300+ pages of dark fantasy and the latter a slim novella set in the real world. It was a coincidence that I happened to read them successively, and I think if I hadn’t read both, if I’d only ever read either one, I might not have posed this quintessential question I’d like to pose to you. What genre, or style of writing, better reflects our modern existence: realism or irrealism? And, what is more important: to recreate the world around you and evoke an emotive experience that possibly transcends it, or to mine a thoughtspace threading out inner realities?

I’d like to take each book in turn as examples of their genre and let me think about these questions.

Irreal

“Do you ever write a story that isn’t weird?” A friend of mine asked me this question the other day. I told her I didn’t see the point. I write stories to express some inner truth of myself, and a realistic story imitating my own life or someone like me would only be redundant. I wanted to write stories that limned the subliminal. I wanted to explore only interiority, justifying my self-indulgence as microcosmic. I thought that my subjective feelings could somehow reflect objective, grander-scale issues. But I didn’t write about my feelings in a diary, emo way. I hid them buried deep under imagery and metaphor.

It was because of all these things that I was attracted to The Great Lover by Michael Cisco. Although not set in a traditionally otherworldly fantasy land, it refuses to describe a real world of any kind. It starts in what might be our own reality but quickly transforms everything into landscapes of pure language. The Great Lover doesn’t describe a real world; it is a real world. By eschewing any semblance of “reality,” it itself becomes hyper-real, the only reality we can be ensconced in and enveloped by. The words themselves and the emotions they evoke are the terrain for the Great Lover to frolic in.

It starts with the protagonist, only ever deemed the Great Lover, dying. He dies and his afterlife or resurrected body or zombie soul carries on trudging through sewer systems, given power. One of his powers is the ability to build a Prosthetic Libido for a scientist who can’t be bothered with his own urges as they distract him from his work. So the Great Lover cobbles together a robot golem to bear the burden of all of the scientist’s lust.

Even though there are these ideas and sometimes only ideas devoid of plot strung together, it was the prose that really encapsulated the tone of the novel. It was rich and chthonic, transporting you into different thought processes where pure emotive mandates were viable.

The book is published by Chômu Press who champions new irreal novels, works that explore the way life feels and not the way it occurs merely to our primary, primate senses.

In a chaotic world in which “truth” and verifiable facts seem to be a commodity, it may be of more value to trade in concepts.

This isn’t fantasy genre with wizards, dragons and zombies. This isn’t Twilight.

“It’s like time travel or music. . . . Don’t try to fit it all together into one story line, but transfer from line to line,” it says metafictionally. The book is self-aware and uses itself to its own end.

Real

After reading The Sensualist, I began to reanalyze the possibility of writing stories that were based on real experience. Because the environment is real, emotions evoked feel real as well.

The Sensualist doesn’t just take place in the real world, but specifically Baltimore. Torday, by reducing the focal point of his gaze, is able to make subtle and passive generalizations that are universally applicable.

The story tells “[t]he events leading to the beating Dmitri Abramovitch Zilber and his friends would administer to Jeremy Goldstein.” It is told in the first-person narrative of Samuel Gerson who falls in love and tries to stay true to new friends.

Readers can identify with a story set in reality or a realistic setting. They are more easily able to comprehend and empathize if they are not always required to decode the language. There is a given template which we all understand as the thing we have been raised in and guided by. Stories set in the real world obey laws and theories that we are familiar with. The readers can exchange themselves in the roles of the characters even if they don’t understand the characters’ exact motives or actions.

Because realistic story-telling is so enterable, it also has the potential of being less engaging. There is a thin line between the familiar and the rote or boring. It is possible that the flaw of realism lies in its closeness to reality, a reality that has its moments of overwhelming boredom. In human experience there tends to only be a handful of distinct stories, but a million ways to tell them. Which is why I left in all of those qualifiers like “possible” and “potential.” In Torday’s hands the story never feels stale even though it is intentionally modeled after classic literature. It directly points out its homage to The Great Gatsby and The Idiot, which strengthens the prose as part of a lineage.

In the real world with real problems, the only solution or salve must be couched in experiences that reflect that reality. Torday’s story is structured so that you feel every emotion as it piques itself viscerally towards its conclusion.

Epilogue

There are strange parallels between The Great Lover and The Sensualist whose titles might almost be interchangeable. They both deal with unattainable love, alienation, and the rites of tribes. They each use exquisite craft of language to evoke their respective ethos.

Here are passages from each that could almost be describing the same scene but to disparate ends:

I pulled her to me by her upper arms. I put my bare arm across the back of her neck and mashed the top of her head against my face. The move was clumsy, and after I had acted I hoped that at least some semblance of intimacy might come across. She pulled away. The momentary rejection of it made me want to grab her, hold her against me. . . .

I got in my car. In the rearview mirror I saw that Yelizaveta was watching. She had already lit another cigarette, and as I pulled away, the burning red ember glowing between Yelizaveta’s fingers became the only thing clearly visible.

I live borne up sustained held and tensed in a gossamer medium of will. Walking up the hump of the street, I have a yen to lean forward arms outstretched. Its slope receives my remains as easily as if they were tipped from a can: and this vile city that barks its hate at me from passing cars, whose buses and streets roar hate at me, whose hysterical citizens recoil from my bland, sallow, wickedly-vacant face. No I don’t belong among you with my nails imbrued in the loam of graves, my breath foetid with my own stale words. Coiled like a turd on my warm mattress, nestled in a chilly reckless draught I bring with me wherever I go. I am a spacious ruin. I am made, and despicable, and I will recount to you your crimes against my sainted person like beads of glowing amber. I have an excellent memory and nothing to gain from forgiveness; I have stored up the venom of blighted days, and trample out your pollution, your stupid trouble, your irreverent work. The music of my soul the world hates.

Ah, Vera!

In the end, I couldn’t tell which was more important or if such a distinction could be made. It might have expected that one relationship to the external world – mirroring or symbolizing – would be superior. But I just couldn’t determine the winner. It is like pitting photography against abstract expressionism. I would definitely recommend either / both of these books to see for yourself which reflects your own worldview.

Grooving to Characters that Feel Vital and Awesome and Flawed

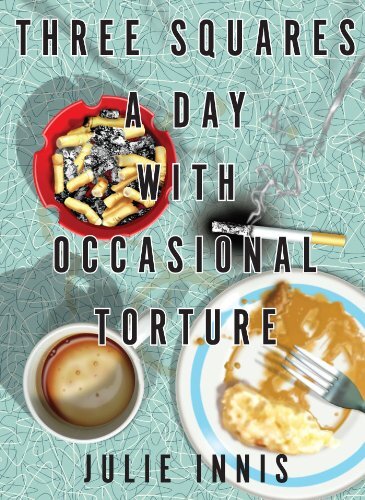

I first encountered Innis’s fiction at a reading in Manhattan, the attentive audience decked out in dark jeans and well-pressed button-ups, faces freshly shaved or tastefully made-up. Innis did everything right, I thought.

I cannot write a short story to save my life. Someone screwed me up somewhere along the way, either in high school English or college lit, or perhaps I should blame reality television or NPR news, or maybe it’s just a personality flaw – I am, after all, a consummate neurotic, secure enough, at least, to admit that I’m often uncomfortable in my own skin. Whatever the case, I suffer under the illusion that short fictions convey deep meanings, that they wrap tough little nuggets of truth in sweet story, that they communicate, that they do something.

Of course, this could be nothing more than a sign o’ the times, as we seem to think reading good for us the way eating spinach or running 5ks are, or can be. When I taught middle school Humanities, as I did for four years, I needed to prove via tests and five-paragraph essays that my students could dissect, summarize, and interpret a short piece of fiction. (No one really cared if they actually enjoyed reading.) “Everything is quantifiable,” my wife told me the other day, echoing the sentiments of educators across the country. But she teaches environmentalism and botany, where it’s clear, isn’t it, if a child can identify the parts of plant? How do we know if a kid ‘got’ a story?

Well, I’ll tell you what I got: a deep and abiding love of short fiction, along with a complex about writing it, a self-conciousness so deep, a set of approaches and questions – What’s my story’s theme? Who’s the protagonist and how can I show things about him or her? – that strikes me as entirely wrong, all work and no play, all head and no heart.

Julie Innis to the rescue! In an interview on Necessary Fiction, Innis said:

I think, and I say this as a former English teacher of fourteen years, one of the worst things to happen to “literature” is the demand from readers for analysis at the expense of empathy. When we teach young readers to hunt for clues to character, specific lines or gestures that are meant to reveal some sort of “deeper meaning,” I think we’ve pretty much fucked the whole thing up.

Amen to that, sister.

And now here she is, swooping down with her first collection of stories Three Squares a Day with Occasional Torture like a literary Avenger. I first encountered Innis’s fiction at a reading in Manhattan, the attentive audience decked out in dark jeans and well-pressed button-ups, faces freshly shaved or tastefully made-up. Innis did everything right, I thought. She took the stage with seriousness and poise, and then with egergy and engaging eye-contact read a story that featured the word ‘poontang,’ not once, but six times, if you count the variations ‘poon’ and ‘tang,’ as in, ‘Got the taste for tang when he was in Nam.’

“Do,” the story’s called, as in dojo, as in karate, as in ‘The Way of Do,’ ‘The Way of Action, the way of kicking some ass,’ of laying ‘the beadown.’ Nuts are shattered. Handjobs given. The tragedy of teenage angst plays out in all its vulgar extremes: sexual longing coupled with insecurity, boys posturing as men, attending bahmitzvahs and teasing exotic fish.

Carol Burnett is attributed with saying “comedy is tragedy plus time,” a cliché I picked up through Woody Allen’s movie Crimes and Misdemeanors. The fumblings of two adolesent boys trying to learn karate, and how to be men, are funny only when seen in the rearview mirror. To the kids in the moment, the stakes are all too real, the thought that the ‘poontang rainbow’ might be forever out of reach and maturity unobtainable, terrifying. “If you don’t laugh, you’d kill yourself ” — now that, Woody Allen did say.

Comedy can seduce you into wrestling with some of the fundamental issues of being human, and yet, comedy is unquantifiable. Explain a joke and you sap its punch-line of humor. ‘Laughter’s the best medicine,’ a husband tells his wife who’s dying of an inoperable brain cancer in Innis’s story “My Tumor, My Lover.” The wife names her tumor George and imagines what kind of man he might be if she could crack her head open and haul him out, as Zeus did with Athena. The woman’s wry moxie in the face of death has you grinning so hard, you’re only just aware of the crushing sadness lingering beneath her cracks, a minor-key counterpoint to the story’s light-hearted melody. It’s a lovely feat Innis accomplishes.

The stories in Three Squares a Day with Occasional Torture brim with imagination – a woman carries on an affair with a fly, the girl on the Swiss Miss box, Swiss Miss herself, comes to life and man, is she one nasty girl – and yet the work never feels unrealistic. I know that doesn’t quite make sense, but follow me for a moment. Like the work of Karen Russell or Haruki Murakami, Innis’s conviction in her imagination is such that she doesn’t try to lay it all out for the reader, sacrificing illumination for pontification, instead she seems to assume that you’ll hang with her sharply precise, rhythmic constructions and haunting imagery, and so you do, grooving to characters that feel vital and awesome and flawed, and awesomely flawed.

Innis follows the opposite impulse of what the over-anxious, over-workshopped writer does on the page, providing an antidote to the antiseptic world of “great literature” with its accumulation of analysis-ready details, quantifiable gestures, and grandiose emotional arcs that often lie only one step removed from melodrama. She reminds me of an ancient shaman, perhaps not so different from the Paleolithic cave painter in Chauvet who sketched a woman’s nether regions attached to the head of a bull, as seen in Werner Herzog’s brilliant documentary Cave of Forgotten Dreams. Herzog shows the evocative image, then cuts to a scientist talking about the primal importance of the combination of woman and bull, as evidenced by the myth of the Cretan minotaur and Pablo Picasso paintings like Guernica. Quantifying, quantifying, quantifying.

We’re talking about poontang stuck onto a bull’s head! Beautifully sketched, powerfully moving, and also funny. One can imagine the shaman giggling while he sketched it, and Innis would be there, laughing along with him. Sometimes, one should experience pleasure – of laughter, of emotion, of story – and nothing else need be said.

1st Annual Prose Contest Results...

Thank you to all who entered and gave us this opportunity to read and consider your work.

Thank you to all who entered and gave us this opportunity to read and consider your work. We hope to host many more contests over the course of many more years, so it is exciting for us to have received such a large and impressive, wide-ranging pool of submissions right out of the starting gate. Thank you again for considering us as a possible home for your work.

Winner:We are pleased to announce that Molly Gaudry has selected Liz Scheid’s Blue Hearts: Notes on Loss, Motherhood, Language, & Other Things for publication as the winner of The Lit Pub’s 1st Annual Prose Contest. Blue Hearts will release in time for AWP 2013 in Boston.

1st Finalist:Sire Lines of America by Adam Peterson

2nd Finalist:Still Places to Go by Paige Taggart

Honorable Mentions:Cockpuncher by Zack Powers

Collected Alex by A. T. Grant

Familiar Animal Engines by Gina Keicher

Toro! A Memoir in Essays by Chris Wiewiora