Poetic Explorations of the Chaos We Create: A Review of Kristin Bock's Glass Bikini

This is the world of Glass Bikini, a new poetry collection by Kristin Bock that brings a premonition of the future through prose poems that craft a world filled with bouquets of rifles, rabbits taking over the world, and monsters with soldiers pouring from them.

There is a world where art has become extinct. In this place, we search aimlessly for some sense of wonder, losing ourselves in the chaos we create. In this absence of art, perhaps we create monsters to fill the void, to at least feel some bit of emotion from the hordes of creatures scratching and clawing at the empty spaces left over. This is the world of Glass Bikini, a new poetry collection by Kristin Bock that brings a premonition of the future through prose poems that craft a world filled with bouquets of rifles, rabbits taking over the world, and monsters with soldiers pouring from them.

In Bock’s alternate universe, we are immersed in a carnival ride that questions and interprets how our current reality could easily follow a much darker timeline. In this world of monsters and chaos, happening “after the extinction of whales”, in which trees as nourishers become murderous “flame trees”, we are instantly and viscerally reminded of the fires that have ravaged Australia, the Amazon, and much of the western United States. And where fire once may have signaled a renewal of forests and the promise of rebirth, we are now trapped in a purgatory of flame and destruction brought about by ignorance and indifference. Throughout the book, Bock weaves the narrative as a poetic comparison of our reality through a desolate and detached, voyeuristic observer as we are left to piece together a clarity and identity while surrounded by a dystopic tempest. In Bock’s world, it is the poet that speaks truth, which resides in a cascade of words that thrust us directly into the chaotic despair of a world on fire, the awe of monstrous intentions, and the dystopic visions that exist in our everyday lives.

However, Bock’s work is not a simple metaphor that one can easily identify and say ‘Ah yes, this is our future. Let us be sad.’ Rather, like our actual world, the truth is much more ephemeral and everything that takes place is often beyond our grasp. This is especially resonant in how she evokes the crucified feminine that society has sought for millennia to control, while invoking questions about a broader responsibility to a suffering earth. In these moments, Bock brings the best poetic intentionality through an invitation to the true monsters of the world; an invitation to come and find a place in the nothing that is left, with the poet more than suggesting these monsters may fit in just fine in the world we are creating.

“Come bomb cookers, come poison makers, come girl biters, come water boarders, come dress torchers… there’s a place for you here, inside my vacuous core of ice and ash.”

Throughout the work, these themes emerge time and again, with the poet providing commentary on the destruction of the planet while intertwining the commentary with our world’s underlying hatred for the feminine. Each poem builds and each subject suggests the next, leading us down a path of exploration of fear, confusion and destruction, as well as growth and understanding. This work is both an interpretation of our future and also our present. In Bock’s world, robots are “seduced by pageantry, white kites and waving” and they “jump for the fame.” Bock’s alternate world allows us to question what is happening and perhaps, what we are allowing to happen and to wonder if she is right when she says: “without their adoring fans, pole-vaulting robots would be nothing but cans crying into themselves.”

Bock suggests we will “die in a bed of your own making” giving us a dire warning but also a fantastical place where none of this is actually real and we still have time to make sense of these empty spaces before the monsters truly emerge. Perhaps, the poet seems to imply, there is still time to revive the artistic self, the sense of wonder, and make things right.

By the end of the work, is it clear the poet speaks more than a universal truth. Rather, she is a guide to help us on a journey of poetic exploration. As readers, we can jump in and try to figure out some of the greater questions before it’s too late.

Or maybe none of this exploration is anything but a vague reflection of an extinction-level event and at the end there was “Only a girl who turned into a bird and flew next to you for a time.”

Open Secrets: A Writer’s Field Guide for the Digital Age

The book emphasizes how an effective marketing strategy should begin long before your book is in the world, and in swift segments breaks down the blueprint for making this happen.

When I stepped into Denver’s literary community about ten years ago, I was entering a big world doe-eyed and ill-prepared as I could be. I didn’t have a college degree, I knew nothing about how to get published, and I’d never hosted a literary event in my life. For what it’s worth, I did find my way. I started attending open mics and listening to what the poets were saying, how they promoted their works, and I watched what they were doing on social media. When I decided I wanted to publish books, Google was a good friend. Over the course of that ten years, I went from a scrub to running a well-known local press having published eight titles and hosting hundreds of events both locally and across the United States. What I wish I’d had from day one is a guidebook like Tupelo Press’ new release Open Secrets: The Ultimate Guide to Marketing Your Book.

Tupelo is the perfect press to release a book like this. Founded in 2001, their twenty years of knowledge shines through, as does a pragmatism that I’m afraid could be lost if one of the big five publishers attempted to publisher a similar book. It’s apparent that Tupelo has a history of what they refer to on their website’s call for submissions as “energetic publicity and promotion.” That energy is contained in the dense sixty-some pages of Open Secrets.

Open Secrets acknowledges the necessity in our times for an author to also be an avid marketer, extra timely in its considerations of publishing in the age of COVID-19. They approach their strategy of marketing in the three sections of the book: image, industry, and the publisher’s role. The book emphasizes how an effective marketing strategy should begin long before your book is in the world, and in swift segments breaks down the blueprint for making this happen. The guide looks at so many questions I myself had as a young person entering the literary world, such as how do I diversify my efforts? How do I find my people? Does word-of-mouth really work? It also answers some common curiosities, such as how long before a release does a press promote a book?

The book functions not only as a go-to for best marketing practices, but also as a road map to other valuable resources. Open Secrets is the kind of book I’ll keep beside me at my desk, ready to reference a plethora of websites and other resources for further expansion on things such as pre-launch strategy, online and in-person communities to engage with, and a full-on “Review, Interview and Submission Directory.” In the later chapters of the book, Tupelo even expands to draw on the resources and wisdom of some great Tupelo authors’, sharing quotes and successful manners of approaching the often-intimidating world of publishing and the marketing that inherently comes along with it.

As I look to my next ten years in the literary world and onward, I find myself grateful that Tupelo’s best kept secrets have been released out into the open, accessible to those who need them the most. Open Secrets serves as an excellent companion to any author, publisher, or book marketer looking to be in conversation with a press of proven merit.

Walls and Mirrors: Enacting the Howls of War A Conversation with Deborah Paredez about her newest poetry collection, Year of the Dog

When I was 12, I went on a road trip to the Vietnam Memorial. Its granite was so polished that you could see your reflection and were thus implicated in the losses carved into its walls. Writing in 2018, the year with the greatest number of school shootings in America, I wanted the reader to experience being separate from the historical subject and yet included in its present-day impact.

Deborah Paredez is a poet, ethnic studies scholar, cultural critic, and longtime diva devotee whose writing explores the workings of memory, the legacies of war, and feminist elegy. Her latest book, Year of the Dog (BOA Editions 2020), is a Blessings the Boat Selection, Poetry Winner of the 2020 Writers’ League of Texas Book Awards, and a finalist for the 2021 CLMP Firecracker Award of Poetry. It tells of her story as a Latina daughter of the Vietnam War.

*

Tiffany Troy: Could you introduce yourself and talk about the history leading up to the writing of Year of the Dog?

Deborah Paredez: I am Deborah Paredez and the author of Year of the Dog. I started writing poetry when I was 12 years old and read Trojan Women for the first time. I became completely enamored with that play and obsessed with Hecuba in particular. It was around that time when I became aware of the silences in our home around my father's participation in the Vietnam War.

In some ways, my understanding of myself as a poet was tied to the experience of being the daughter of war and tied to the tradition of feminist elegy. The motif of Hecuba crying out plays itself out in this book and it took thirty to forty years to write the book that in some ways I had been meant to write from the beginning.

Tiffany Troy: How is Year of the Dog a book “with and not just about your father”?

Deborah Paredez: In my childhood, because there was so much silence around the war, I often sneaked into my dad's closet where he stored his photo album from Vietnam. I would pour over these photo albums like a kid reading Playboy. I knew instinctively that perhaps answers to the questions hanging in the air about my household could be found in these photos.

Even though I thought I was being sneaky, my family knew. Many years later, when my family was cleaning out the house my mom said, “I'm going to send you these photos that I know mean something to you. You can scan and then send them back to us.” So I did. I realized these photos held a very important archive not just for my father's experience, but also of Latino participation in Vietnam. This experience, in turn, has historically been and continues to be documented incompletely. As a result, I wanted to engage deeply with those archives and to co-create this work with my father. I understood that we were co-creators of this work since he was the photographer whose work I was engaging through my poetry.

On a literal level, I asked for permission to use my father’s archive. Being “with” my father, as opposed to “about” him also had a political meaning. It meant carrying a sense of reverence for him and his story from the perspective of the daughter, as opposed to transforming him into an object of study.

Tiffany Troy: As a poet, it always felt clear to me that the stories of the Vietnam War are told through your lens as you father’s daughter. How was the process like, weaving personal artifacts with iconographic images of war at home and abroad?

Deborah Paredez: Finding my father’s photographs was important in a number of ways. One aspect that really mattered was that the photographs were in the same medium, photography, by which we have often come to know about the Vietnam era. The Vietnam War was the most photographically-documented war because reporters had unrestricted access to combat. As a result, the reporters brought about those images that we saw on the nightly news with images of the dead. These images ultimately fueled protests against the war.

The photographic image, however, has in many ways over-determined our engagement with and our knowledge about that war. I was interested in defamiliarizing the photographs for the readers/viewers. Even as the photographs document, they have also inured us to those horrors. I wanted to re-familiarize us all with these horrors through an aesthetics of fragmentation, collage, juxtaposition, echo, etc. I wanted to implicate the history and stories that iconic photographs of war tell by buttressing them against my father’s photographic archives to expose the racialized terms of inclusion, to foreground the often overlooked Black and Brown experiences of war.

Tiffany Troy: That triptych with Mary Ann Vecchio in the middle and buttressed by the arm of the “napalm girl” Kim Phuc on either side definitely challenged my understanding of war through the archive. What guided you to juxtapose photographic fragments and how do your father’s handwritten photographic captions fit into the iconography of the stories you're weaving together to allow us to view the Vietnam War anew?

Deborah Paredez: I was very much guided by a poetics of fragmentation in bringing down iconic photographs to an arm, for instance. I juxtaposed the images through resonance or a kind of image rhyme visual rhyme or by images that are stitched together so they exposed the seams of each other. We knew the rest of the picture and implicated ourselves in our familiarity. I also wanted to show that there was only so much I could reclaim in excavating my father's story and the stories of soldiers like him. There was a partiality—in all senses of that word—because I was speaking as the daughter of this experience.

Using my father’s captions that he scrawled on the back of some of his photographs was important because of the way by which we're trained to understand the photos. I wanted his voice to be present and handwriting always implied the presence of the body. I fragmented and excerpted those captions so that as to foreground the sense of partiality, the elusive subject that was always present in this work.

Tiffany Troy: You made sure that your father's face did not appear in the collection. Why?

Deborah Paredez: It's important to always interrogate our attempts to represent the other, whether that other is my father or Kim Phuc or Angela Davis, and to understand the power dynamic between the writer and the other. For me, it was to present while emphasizing that I can only ever grasp partially my father’s experience. As such, preserving his privacy and rendering his own subject preserved and inaccessible to me and to us is important.

Tiffany Troy: How do you use songs and howls to add texture to your collection?

Deborah Paredez: In a very early version of the poem “Hecuba on the Shores of Al-Faw, 2003,” a sonnet, I realized I was being a little too tidy because I was trying to preserve the 10 syllables per line. Tinkering with the poem helped me realize the ways in which the book had to reenact the indecipherable howl.

I tried to do that in the final poem in the collection, the untitled concrete poem that repeats and fragments the final lines of the second poem in the book. I hoped to leave the reader with a "pang led" howl, wanting to require the reader to make the sound so that we're all heaving together, so that we see the limitations of language.

We also see the howl in “Year of the Dog: Synonyms for Aperture,” in the howling of “O—H—I—O—I—OH—OH—OH—” and in the Janis Joplin reference in "Self-Portrait with Howling Woman."

Tiffany Troy: Year of the Dog is the product of meticulous research. Turning to the specific example of the Edgewood Elegy, what is the nitty gritty process like?

Deborah Paredez: The nitty gritty is always boring, being the nitty gritty. Writing the “Edgewood Elegy” was difficult because Black and Brown people’s relationship to documentation has always been overdetermined yet un(der)-documented within the larger US imaginary despite having served in high numbers proportionally in the Vietnam War.

When I was writing Year of the Dog, Ken Burns’ “The Vietnam War” came out. Black and Brown soldiers are almost nowhere in that multi-episode documentary. Part of the reason we remain undocumented even in the most valorous moments, is that during the Vietnam era, Latinos were still (mis)characterized racially as White. Researchers literally counted the Spanish surnames in the casualty list to get a guesstimate.

Fortunately, in the Edgewood case, there was an actual monument in San Antonio documenting the names that the community could document. I poured over those names, plugging them into governmental and other databases. One site listed Vietnam War veteran casualties and whatever additional information that the site could collect, like if they were a Corporal or what unit they served in, or if they had siblings.

While there were many pockets of no information, I wanted that poem to capture both the absence of these men and the absence of the documentation and my struggles to attain that so that is how that poem came about.

Tiffany Troy: How do the three epigraphs set up the realities, narratives, and mythologies of the three sections that follow?

Deborah Paredez: The epigraphs very much provide a Venn diagram for the book.

I wanted the quote about Hecuba from Ovid’s Metamorphosis to be the original mythic cry from which this book makes its echoes. I also wanted to signal that while the stories of people of color I tell may appear very regional, it is a tragedy or story worthy of the epic treatment. In Adrienne Rich, I find a feminist committed to bearing witness to experiences that may not have always been hers. Her explicitly feminist ideology and feminist poetics was important in my own upbringing as an unabashedly feminist poet. June Jordan speaks to the very particular experience of racialized subjects. In her case, speaking about Black communities, she insists that we respond in ways that correspond with the scale of our tragedies. Within the context of this country her insistence that we are beyond time for being reasonable echoes through all three epigraphs. In these senses, all three of them are about that howl, which set the tone to guide readers into the mode that the book would register in.

Tiffany Troy: The second section speaks of Kim Phuc’s extraordinary and one-of-a-kind story. How do you bring yourself and your culture into her story?

Deborah Paredez: As a work of documentary poetry my book is invested in exposing the ideological work that photographs and other official archives do. In its aspirations toward feminist elegy, it is also invested in exposing the gendered terms of war imagery. In the collection, I explore the ways in which “othered” women, whether they are Black, Vietnamese or the teenage runaway (in the case of Mary Ann Vecchio), have been positioned in war photography, both in service of war or its resistance.

Nick Ut’s photo of Kim Phuc is exemplary of how war images often perform a kind of violence, even as we understand that immediately after taking that photograph, Ut helped Kim Phuc get to a hospital. It took a lot of soul searching to find a way to reach across time, space, and other divides toward Kim Phuc’s specific story with a sense of care and commitment to retrieving the subject from the ways she had been rendered an object. Part of it involved reading into Kim Phuc’s history. I relied heavily on a great book called The Girl in the Picture by Denise Chong, which spoke of Kim Phuc both before and after the moment captured by Ut's camera. Kim Phuc spent some time in Cuba. While there, she briefly took a trip to Mexico. In that initial trip, she was hoping to defect. Kim Phuc and her coterie visited the Temple of the Sun and while she decided in that moment that her overseers were too vigilant, I was struck by her own journey that took her to places that have particular resonance for me and my people. I was interested in having Kim Phuc be in a mythic location, both situated in and trapped by history. So I latched on this tiny moment in her own biography and did some documentary speculative work that that one does when you're a documentary poet.

Tiffany Troy: How do you incorporate Vietnamese geographies and the Vietnamese faith into the poems about Kim Phuc at the Temple of Cao Dai and the Temple of the Sun?

Deborah Paredez: I was very fortunate that a dear friend of mine, Hoa Nguyen happens to be a Vietnamese historian. She became a consultant to me about not only how to be factual but also how to incorporate certain elements with a kind of cultural specificity. I didn't incorporate very explicitly a lot of iconography or spiritual elements, or even mythic elements of Vietnamese Buddhism, aside from what Kim Phuc’s own biography engages in.

It was important to pick up on the biographical details: Kim Phuc and others were at the temple hiding out. The temple is a sanctuary that is no longer safe in the war and its aftermath. It was really important for me to begin in the temple, in the moments before the bombing, to emphasize that Kim Phuc exists before that moment, just as she exists long after it.

Tiffany Troy: How do you incorporate and refract the different identities through place names and languages other than English in a predominantly English language collection?

Deborah Paredez: Year of the Dog addresses both the insufficiency and violence of language. Hecuba was so grief stricken that she barked or howled. The most mundane or clichéd form of language, like the idiom, possess a kind of violence that is largely unseen.

With the use of Spanish and English, I was chatting with my friend, Sadiya Hartman, about the book and she said something like, "It makes sense that you would be writing about Hecuba because of La Llorona.” La Llorona was the mythic Mexican folkloric figure of the weeping woman. Until that moment, I hadn't made that explicit connection, but it made so much sense, and I was grateful for her insights. Putting La Llorona alongside Hecuba reflected my own poetic and artistic traditions. It was important for me to have the reader see that La Llorona is just as kind of mythic and as epic and important as Hecuba.

Similarly, much as Latinx communities are often predetermined in terms of language and documentation, I think of the meaning of having my last name spelt with a Z and not S in one of my poems. What does it mean to have a last name as “walls” (paredes) misspelled?

Tiffany Troy: Earlier, you were talking about “Paredez” meaning wall misspelled. You also wrote of Maya Lin’s Vietnam Memorial becoming a mirror in the collection. How does the wall versus the mirror dichotomy play into your collection?

Deborah Paredez: The walls and mirrors idea came about in a very literal way. When I was 12, I went on a road trip with the neighbors to the Vietnam Memorial. It was the 1980’s, not long after the war, and I remember visiting the Memorial and being very moved. The Memorial’s granite was so polished, purposefully so, that you could see your reflection and were thus implicated in the losses carved into its walls. Beyond this moment, I was writing this book in 2018, which was, at that time, the year with the highest number of school shootings in the nation's history. I wanted the reader to experience being separate from the historical subject and yet included in its present-day impact.

Tiffany Troy: How do you approach talking about the way in which the women are grieving through the loss through their fathers, brothers, husbands, and family members?

Deborah Paredez: It’s definitely dangerous, right? With the mythic women, it's a little bit easier because they're not going to be so damaged by my clumsy attempt. But historical women, like Deborah Johnson, Angela Davis, Kim Phuc and Mary Ann Vecchio, among others, were women to whom I wanted to pay respect. I found that if I wrote in the second person, almost like I was writing a love letter to them. The second person, then, shows the poet genuinely attempting to reach across time and space to honor them.

Tiffany Troy: How do you both honor veterans and protestors who want out of Vietnam?

Deborah Paredez: Many veteran writers before me get at the complexities of the Vietnam War. Yusef Komunyakaa is an exemplary model of a veteran poet who both writes about his own experiences in Vietnam as a Black soldier in a way that's not jingoistic while also not dismissive of the particular struggles faced by soldiers like him.

In my collection, I wanted to show how in these imperialist projects, those who are often most devalued are summoned to maintain or expand the reach of the colonial order. For me, then, it was important to begin with the story of my mother and grandmother. As much as this book is about my father, this book is an origin story about how I learned to grieve and to shout out against war from maternal figures.

I wanted to foreground how Latino experiences, even in regards to Vietnam War, were just as diverse as White experiences. In “Self-Portrait in One Act,” which features the fascinating story of Delia Alvarez and her brother Everett Alvarez, Delia becomes an anti-war activist even while her brother is being held as a prisoner of war in Vietnam. Delia doesn't want to be deployed in the ways that the POW families are often deployed. She's like, “No, you will not use me that way right, because what you are doing is wrong, even as I am honoring my brother's experience there.” Delia is a perfect example of the kind of experiences that I wanted to bring to bear.

Tiffany Troy: How do you use poetic forms to challenge the propaganda of war?

Deborah Paredez: Documentary poetry is very much invested in using a poet's intimacy with the vicissitudes of language to trouble the document, whether that document is a decree, an edict, a speech or photograph. Coming out of that tradition of documentary poetry, I am invested in both troubling and generating documentation through a poetics of erasure, repetition, and idiomatic (il)logic. How do we rearrange the idioms so that they tell a different story about war and warfare? For me, this approach to poetics helped me think through and beyond the particular ways that language gets debased in war propaganda.

Tiffany Troy: In the “Edgewood Elegy,” the poem visually takes the shape of little, lined up gravestone markers. Other poems take the form of lists. Does the poem like find it's form or do you choose the form intentionally and then the contents are to come to be?

Deborah Paredez: More often than not, the poem finds its form. So, in the case of “Edgewood Elegy,” as I was trying to gain information about these casualties, I just kept coming up again and again against the silence in the archive. Part of me wanted to build a poetic monument—there was certainly an actual monument built in San Antonio—and to render within that monument the silence. I wanted to stage the monumental-ness of that silence, to insist that we disorient or reorient ourselves to acknowledge this grief, so you have to actually turn the page, to literally turn the page to see the history.

In other times, I deploy received forms, like in the opening poem, “Wife’s Disaster Manual,” which is a villanelle. The villanelle in its obsessive repetition, is ideal for the insistent instruction. I found it was a perfect container for holding Lot's wife's insistence that we stand still, and keep standing still, and still, and refuse to look away from the burning city.

As a formalist, I am interested in how form determines our way of knowing. I'm not just reverential toward form but deeply curious about finding its seams so as to undo them. Sometimes the form or the photograph need to be deconstructed, rendered, or ripped apart at times, to spill out of the frame.

Tiffany Troy: In closing, what are you working on today?

Deborah Paredez: I'm working on a work of literary nonfiction, a memoir about my life with divas and their role in my life. About how divas guided me as a Brown poet, thinker, essayist and performance critic. And about how, even though we often associate divas with kind of the singularity, divas have actually taught me to really love and be in relation to virtuosic messy women and not be afraid of them. And I’m also working on some prose poems or lyrical essays about the sea and all of the things that the sea evokes for those of us people of color.

from an identity polyptych by Tameca L Coleman

What are you? Not even a bird’s wing because

birdsofafeather. You wish you knew how it would feel to be free.

Like a bird in the sky. How sweet that would be! But is not a bird

anchored to its flock? The arcs and dots are echomarks

flying out of your mouth.

“I do not know when reconciliation comes”

I do not know when reconciliation comes

“I thought there was a thing called forgiveness, and if you don’t want to forgive and if you don’t pray for that person, it never be right.”

An activist writes: “Reconciliation is dead,”

the captioned photograph of a beautiful Native woman

shouting, a red hand painted over her mouth.

I am reminded of a man who is dead now

and who admitted to me

the rape on his record

before asking me

to stand between him and community,

some of whom knew, some who didn’t, to soften, I imagine the knowledge of his past

and I asked a friend who had been gang-

raped if they thought a rapist could be rehabilitated.

and I remembered the traumas in the bodies of those I worked for,

and wondered what kind of person I would be if I said yes.

My mother’s neck still shakes, and the only power she has these days is in safeguarding her broken body.

I had a friend who had smooshy feelings for someone, and for his warmth another man ripped his insides, and left him, asking if he liked that.

He had no one, so though he didn’t like that, he accepted the only security he thought could be found, and then the rest of them, too, had their turns. This is the price he paid for a home, he told me, and he thought that maybe he deserved it, the taking and tearing of his insides. He went back again and again.

A lover once said, “Your body is not always yours. Let me have it.”

A lover once said, “You are being preserved for me, and I will find you. Do you like to be raped?”

A lover once told me that I better not dare claim anything other than love, my placement in his bed secured by the rifle within arm’s reach.

A lover once told me about the “sanctuary” found where two men made all the children they saved trade sexual favors. She is nostalgic about this house, and speaks the magic of floor beds and shared scarcities. This world was somehow better than what she had before, and she sometimes wonders where those men have gone, and she sometimes craves small dusty spaces and booze and shared bread that’s already turning.

Someone somewhere will no longer catcall a woman and yell into her back that he’s talking to her because of the scream that scraped scars up my throat and out of my mouth.

Someone somewhere has eight long scars down his back for trying to force me to take a “picture” to remember him by.

Someone somewhere carries my mother’s stab wound.

I do not know when reconciliation comes.

When you said, “You know, there’s two sides to every story. I guess your Mom did what she did and I just went off.”

I thought about how I hate violence,

and I thought about how we’re facing violence all the time,

the perpetrators of the wounds we carry getting off

scott-free with the language of their gods in tow,

beating us over our heads once again

with demands for forgiveness

songs we do not owe.

You can’t just read your way out of racism. And yet reading with that aim is a powerful and viable first step. And how strange when you pair that against a Black man and his partner creating a space for communing and intervention, full of informative and empowering books meant for the communities they come from, for the communities whose safe spaces are disappearing, for the communities who are being colonized and owned all over again.

The young man who comes to speak to us has grit in his teeth when he says “white liberals.” They are the ones who have money and they are happy to spend it here. Spending their money here makes them feel that they are doing something. They do not realize that even here, they are co-opting intent. They do not realize that even here, in their earnest desire to understand, they harm.

am i an ally?

you can’t read yourself

out of racism

but stacks of books line the desks

and tables,

the bedside dressers,

they line

the insides of my bags.

i take notes and carry

the weight of them.

i underline

and highlight. read with yearning.

the more i read, the more i know

i know

nothing

i bend over the tables, my shoulders

curving over my heart, eyes

strain and water,

my chest heaves.

each book

is a silent soldier

armed to the edge of the pages’

slicing corners see

see

see

how

my spine compresses.

see how

my fingers

bleed.

The Funny Business of Writing: In Conversation with K. E. Flann and Jen Michalski

If we see other writers only from afar, we are aware only of finished products that get published, often announced online with trumpeting fanfare. We never see (a) what didn't get published and (b) the struggle behind the things that did. This lack of information can lead to a faulty assumption that success is frequent and effortless for other writers.

K. E. Flann and Jen Michalski workshopped short stories together for years as part of a writing group in Baltimore (they both hosted fiction-reading series there, as well), and they each published a couple story collections. Their latest books have taken them in different — and yet parallel ‚ directions: Jen Michalski's third novel, You'll Be Fine (NineStar Press), is a family comedy featuring LBGTQ leads, and K. E. Flann's How to Survive a Human Attack (Running Press) is a humor book, the first-ever survival manual for zombies, cyborgs, mummies, nuclear mutants, and other movie monsters. Flann and Michalski got together to talk about writing groups, persistence, and risk-taking, among other things.

*

JM: Congratulations on How to Survive a Human Attack, K. E.! As someone who is a prize-winning short fiction writer, this is a new direction for you. How did the idea come about for the book? Were you anxious about writing for a different audience than say, one that enjoys literary fiction, or do you think there's an overlapping sweet spot of readers?

KF: And congratulations to you, as well, on You'll Be Fine. I sometimes still don't grasp that we are on opposite coasts after being in the same city and the same writing groups for years. It's great to mark this occasion together at long last, not least because I had the privilege of reading early drafts of your novel. It’s delightful. People are going to love it.

How to Survive a Human Attack began when my husband was watching "The Walking Dead" in the other room, and there was so much screaming. Those zombies were getting slaughtered! Someone should really help them, I thought. I wrote a short advice piece, and it was published quickly. Pretty soon, I started to suspect there were other monsters that needed help. I wrote and published a few more and a few more. And here we are.

Monsters are definitely a new audience, although I suspect a lot of us are at least part monster, even if we don't know it. I got started in the "advice" milieu thanks to the story collection, Self-Help, by Lorrie Moore, which revolutionized my thinking about form and tone. I also love pop culture and B-movies. So now I'm the horrible hybrid creature before you. I do hope there are others! We’ll see.

It seems like your trajectory has been the other way. You started with the fantastical in The Tide King, while You'll Be Fine has autobiographical elements, making it — in certain ways, at least — reality-based. How was it different to work on this book as opposed to previous ones?

JM: It's funny you mention trajectory, because when you start out with your first book, there's an assumed trajectory, in genre, in audience, in sales, but my trajectory as a writer (and published author) has been anything but an upward trajectory — it's sort of been all over the place, up and down, different mountains, even. I'm pretty undisciplined in that I write about whatever interests me at the time, because that's where the energy of the words is. And yes, my first two novels, The Tide King and The Summer She Was Under Water, both had elements of magical realism at play, and they were both serious and kind of sad in places. And it's funny, because I would meet people who'd read my books and they'd be confused, because I guess I wasn't morose enough, and they'd say, "wow, you're funny in person." Which is kind of, I don't know, weird? So I knew, at the onset, I wanted to write something a little more accessible and lighter. Something that was more attuned to how I see myself as a person. And yet, it's still a little heavy — I started working on it right after my mom died, and a mother dies in the beginning, so it still manages to squeak in a little bit of serious and sad.

Now you, you're a very funny person, and you have a lot of work out there that attests to that, in McSweeney's Internet Tendency and other places, but when we were in a writing group together, you were working on a memoir about your dog, Clark, and there was some pretty heavy stuff in it. I wonder if a lot of the variation in our work is also the result of just growing as writers and as people. Is there anything that's surprises you about the writer you are now as opposed to the writer you started out being?

KF: Ha! The same thing happened to me. With my short story collections, I had people say, with equal frequency, Wow, that book was funny and Wow, that book was depressing. It bummed me out when people told me that my books were depressing because I didn't see them that way and because I hoped to buoy people with my work, rather than make life feel heavier.

I didn't set out to write humor, exactly. I simply entertained myself writing advice for movie monsters. Then, while I was working on the book in earnest, my dad was diagnosed with advanced, terminal cancer. One night, he fell and hit his head, and he went to the hospital. It occurred at the beginning of the pandemic, when visits were not allowed. We didn’t know he was in his final decline until nearly the last moment. Thankfully, we got him home for his last few hours.

To say I was reeling would be an understatement. As soon we got home from the funeral, I started a period of composing short humor pieces that ended up in McSweeney's, The Weekly Humorist, and other places, while also continuing to work on the book. I probably needed to laugh, but there was also the element that it made me feel closer to my dad because he was so funny. I also wanted to be useful to other people who were suffering, and I wasn’t sure what else I had to offer. I have no idea if reading, for example, the eulogy I penned for Real Pants, actually made a difference to anyone. But I offered what I could. I have only recently felt emotionally equipped to work on the "serious" projects I couldn't face during that time, like the memoir project you mentioned about moving to Europe with my dog.

I wonder if it’s common to write funny stuff when we're struggling and serious stuff when we’re content. Do you find your own emotional climate and your work to have a relationship that’s more parallel? Or what about your work as editor of JMWW journal? Do you ever feel that the tenor of your own work is affected by the pieces you publish there?

JM: Wow, that's tough, and I'm sorry that you went through it. It was definitely a very fertile period for you, in terms of humor, and very bittersweet to know what was underneath the surface while you were producing those stories. For me, although You'll Be Fine did sort of mirror my life at the time and felt cathartic in some ways, most of my work is emotional prepping for the unknowns. I feel like I'm always trying to figure out how to live, because in my real life I feel like I'm just winging it. So my work is often a response to questions I've posed to myself: what if a parent died? What if there is sexual abuse by a family member? What if you could live forever? What if one's life isn't what one wanted it to be? I love that as writers we get to game out these scenarios and live vicariously through other characters and their situations, good and bad. And I love that I get to read other writers' works and respond to their characters also.

I do feel the tenor of my work can be affected by what I'm reading, but it's less emotional and more technical, more craft-oriented. Of course, it's why writing instructors drill their students to read, read, read! I love that sometimes I find the tools to address deficiencies in my own work through other books. For instance, this summer, for fun, I read a lot of Emma Straub. And although I loved the beachy read vibe (I was on vacation), her novels also helped me figure out how to be more accessible to readers through her voice and sentence structure.

Of course, another way to hone one's craft is through writing groups, and you and I are battled-tested veterans! I feel like over the past 10 years we've been members of at least two groups together! What have you taken away from being part of a writing group?

KF: It's funny that you asked about writing groups because I was just speaking to a student today about how important it is to be involved with other writers. If we see other writers only from afar, we are aware only of finished products that get published, often announced online with trumpeting fanfare. We never see (a) what didn't get published and (b) the struggle behind the things that did. This lack of information can lead to a faulty assumption that success is frequent and effortless for other writers.

Being in a writing group with you specifically has always been a masterclass in discipline. You are not only one of the most curious and imaginative people I know, but also one of the hardest working writers I know — always crafting a major project alongside smaller writing projects, as well as editing a literary journal. In pre-pandemic times, you were often running a reading series. Plus, your day job involves using your writing and editing skills. In the groups, I saw how thoroughly you revise, as well as how creatively. I remember you talking about how you wanted to challenge yourself to cut a 5000 word story down to 1000 — and you did it, which required seeing the story from a totally different angle. A beginning writer who did not have the privilege of witnessing your process might look at your five highly-acclaimed books and many published stories, and fail to grasp what goes into that.

I learn a lot besides craft and discipline from other writers when I'm in a group, too. You talked about your trajectory being all over the place, but I interpret that as creative fearlessness. You worked on a graphic novel script, at one point, and I was like, Wow! So that's how you do that? In some way, I probably absorbed a measure of your adventurous spirit, and it no doubt emboldened me to try to some new things, too. When a group works, I think it becomes a kind of organism, providing energy or nourishment to each person. I'm curious to know how you see the groups. Is it the same for you? Even though we've been reading each other's work for so long, I never asked you what the group experience has meant to you, or if the perception of their value changes over time.

JM: Thanks for the nice words! It's such high praise coming from you, whose work I have admired continually over the years. I agree completely with your assessment on writing groups. I've had the privilege of seeing early drafts of your stories, as well as many other writers, and seen the work involved in revising and revising again. In a group, you also see the life cycle of submissions, your own and other writers — I've seen writers have stories rejected twenty times but then get picked up by a high-tier journal! I remember when Roxane Gay had a blog, years and years ago when she was just starting out, called I Have Become Accustomed to Rejection, where she detailed the ordinarities of her day but at the end listed which journals had sent her rejections. It was such a brave blog, in terms of not being embarrassed by rejection but also showing how often you need to submit, to not become discouraged after a few "nos." Anyway, I love the title because, in a way, groups are where you become accustomed to rejection and the grind of the writer's life.

But the group kind of mitigates the grind as well — I always feel very excited after I attend a group meeting, ready to get back to work. Critiques constantly open new windows for you to see things in a different light, new dialogue, and I'm always so excited to respond to that dialogue. There's also the deadline of submitting something to the group that keeps one writing, if you're not inherently self-directed. I also think groups humanize the writing process. It's easy, as you said, to see someone's successes touted on social media and be jealous or depressed, but it's harder to be anything less than 150% supportive when you've had a front-row seat to the writer's journey (and all the inherent stumbles, rejections, and disappointments that happen just as often, usually more). And, in a good group, you trust the writers in it and aren't afraid, as you said, to take chances and try new things without worrying about people judging you.

I think, even outside a group, though, it's important to take chances. Sure, the publishing industry is very much about brand, about building one's platform in one genre or another, I think it's important to write about what resonates with you emotionally, even if no one ever sees it. I've written novels that are just for me, because I know I have a particular taste and the fun for me is in writing it. And I really love that you started out at the very serious literary end of the pool but now you're books about monsters! It's very brave, because humor is hard and can be just as insightful and deep as literary fiction, but then all of sudden you're not supposed to write a novel that's a contender for the National Book Award because you've been pegged as "funny." But I'm totally sure you're going to write a book that's going to be a contender for the National Book Award, so screw those guys.

After writing You'll Be Fine (which is kind of funny but also sad), I realized that novels don't have to be either "serious" or "funny." A good novel can be both, and a good novel should be both. This blew my mind and it's strange that I finally "got it" after writing some pretty sad novels and novellas. Oh, and I wanted to point out that you wrote a freaking craft book (WRITE ON: Secrets to Crafting Better Stories) right before you wrote How to Survive a Human Attack, speaking of creative fearlessness. What are you working on now?

KF: Well, one aspiration is to write a novel, something in the long-form. I tend to be full of ideas. I bing-bong from one short thing to the next. I mean, no regrets. Certainly, my short story skills provided a great foundation for other short-form work, like essays, humor pieces, and the columns that led to the craft book, and short story skills even help my work in the classroom. Aspiring novelists I teach sometimes get lost in the woods of their own narratives, and as someone with a succinct vision of plot, I can help them counter-balance some of that. But can I find within myself the commitment novelists demonstrate to one project? How is it for you working in both forms? Did one come more naturally to you? Were there times in this latest novel when you weren't sure if it would come together?

JM: I tend to keep a lot of balls in the air, working on short stories and novels at the same time (sometimes even two novels, ie, going back and forth between them when I become stalled on one or the other). I'm happiest when I'm working, and it's the process of putting words on the page, rather than the long-term goal, on which I try and focus. It's kind of like running for me, which I know you'll appreciate — run the mile you're in. However, I have a harder time writing short stories, so I admire your succinct vision of plot!

In terms of You'll Be Fine, this novel felt pretty cut and dry while I was writing it — for once, I didn't try to make this big literary statement — it doesn't try to be something it's not. I wanted to write something that entertained the reader, and that's it. That's not to say it didn't go through many drafts to be what it became. And I was very open to criticism from all comers — I tried to recruit as many people as I could to read, and I promised myself at the onset to be very open to any advice because I wanted it to be the best novel it could possibly be and not let my own hardheadedness get in the way.

Critiquing can be hard, though, both receiving and giving criticism. Giving criticism, there's what you think should happen and maybe what you want to happen, but what matters is helping the author get their vision on the page. Conversely, when receiving criticism, it's very subjective, with people saying, "Well, I think that character should be different" or "I don't think that's how this situation should unfold," but how much of the critique is just their personal preferences or how they would write it? Art is really hard. It's not like being an accountant. But you absolutely shouldn't forgo the critique process, because there's always some piece that will resonate with you and you never know from whom it will come. I remember working on a novel when I was in the master's program at Towson, and in my novel critique class there was this guy I just couldn't stand. You know, he was that guy. And yet in one offhand remark, he solved a huge problem hanging over the plot of my novel, so I was grudgingly grateful, LOL. So the process can be infuriating but also mysterious and wonderful — writing in a nutshell.

Speaking of clouds, we haven't talked about that mysterious fog writers must fight through after publication, you know, how to actually get the word out to readers and convince them to buy your book in a field of 30 million others! Has the pandemic impacted your book tour plans, or the way in which you hope to market your book, or maybe some new and different opportunities have emerged in the process? You've been teaching on Zoom now for over a year, and you're such a natural on camera! I would totally go to a virtual K. E. Flann reading.

KF: I couldn't agree more about the experience of being in a workshop with someone I find, ahem, challenging. I have seen this both as a workshop participant and a workshop facilitator. Quite often, there's someone whose interpersonal skills leave something to be desired, and yet has razor sharp insights about the other writers' stories. That's a hard combination. If someone has bad interpersonal skills and little insight about the work, we can dismiss that person's opinion. Or conversely, if someone has great interpersonal skills and great insights, well, we love that person. So in either direction, that relationship is easy. But someone who offers razor sharp insights with a razor-sharp delivery style can be tough to take. And I think the knack to receiving criticism is finding a way to hear that person and even to relish that feedback because it is direct and easy to understand, not obscured by niceties. We don't have to incorporate that feedback, but we don't have the chance even to consider it if we're not willing to listen. I've had the same experience as you have of receiving a key piece of criticism, something that solved a big problem, from someone who rubbed me the wrong way in that moment.

Speaking of big feelings, though, you asked about the post-writing fog — that period of promoting something that's finished. I'm sure you're going through that right now, too, and with so many books under your belt, maybe you can give me some advice. I'm so nervous about the release of How to Survive a Human Attack that I find it hard to focus on loading the coffee maker, let alone on writing something new. Also, I drop items made of glass and bump my head on open cabinets. It's like the Benny Hill show at my house. How do you cope?

JM: Oh no, K. E., I see you! I totally understand. And the experience is different every time you have a book out, depending on your publisher, your intended audience, what's expected of you in promotion. I always tell people that promoting your book is your second job, the one you go to after you get off work (or maybe before work), on weekends, on vacation. You have to keep your book out there, make it feel inevitable in people's lives (and bookshelves) while at the same time not turning people off. It's almost an impossible equation, and people tend to scatter to two opposite poles — those who are too timid, embarrassed even, to promote their work and those who are the marketing equivalent of a flamethrower, piling it on everywhere and anywhere. I tend to fall into the former category (I literally cringe sometimes before I hit the post button to share something), but at the end of the day, the only person who really cares about your book (unless you're Stephen King's agent) is you. No one else is going to do it for you, and although you may have varying levels of help, it's up to you to make the case for your work.

And you should promote it how you're comfortable (or to the edge of your comfort zone). I know someone who only visited book groups — for his debut novel, he scheduled visits with 50 groups! Other people might not be able to handle such repeated intimacy, and maybe online marketing is better for them. Maybe you do a lot of giveaways. For my first novel, The Tide King, I did a lot of readings — I visited bookstores, colleges, reading series, classes, and a few book groups. But I found that I didn't sell many books that way, or I couldn't figure out which venues produced book sales. Once I had an event of 50 people, and nobody bought a book, and another event, 6 people showed up and I sold 6 books (weirdly, they were all bought by the same person — I always wondered what happened to her). It was then I realized, unless you are a highly industry-supported author with some Reese Witherspoon movie option, your book's success is really a crap shoot.

Which was kind of freeing! There's so much you can't control, from how the publisher promotes your book (eg, either spending tens of thousands of dollars on your campaign or giving you a stack of bookmarks and wishing you good luck) to a 2-year pandemic that obliterates family, friends, and book tour. So this time I didn't set a goal for the "success" of my book. I literally don't have any expectations. There was a time when I was extremely worried about being a "successful" author, and it really was depressing and an awful strategy for maintaining a healthy self-esteem. Now that I'm older, it's not the most important thing in my life anymore, thank goodness. (I still have "I'm such a failure" days, but that's sort of like a colonic for my soul.) Being healthy, the people I love being healthy, and trying to have fun amidst random body pain are much more important. Plus, you get to define what makes you a "successful" author. I'm happy my book is out, I'm happy I wrote it, I'm happy that strangers so far seem to like it, and that's good enough for me.

This was a long way of saying, I think as long as you're genuine, people understand, and they're not going to roll their eyes when you've posted for the 50th time on Instagram about your book. It's a hard job, I have an instant soft heart for every post I see on social media of someone hawking their book. Also, I hope everyone buys your book — you always make me laugh, and having your book is like having you make me laugh whenever I need it! At any rate, if I may quote myself, you’ll be fine.

KF: This is reassuring to hear, Jen. I’ve appreciated the advice (from several corners now) to do as much promotion as one is comfortable doing. I mean, if we took that advice too literally, we might do none? But I think the point is that there’s an endless amount one could do, and at some point, we have to say, Okay, I’ve reached my capacity for now.

I wrote the book out of an urge to make people happy. Life is hard, especially now, and what can you do sometimes but laugh? Yet, out of that urge to buoy people in some small way, I’ve ended up the recipient of support from so many people in the literary community. It’s enough to make you think humans are actually all right sometimes.

To Shoehorn a Cat: A Conversation with Reese Conner

The dying or death of a cat allowed for a general exploration of grief, yes, but it also led to questions about what we are allowed to grieve, how much we are allowed to grieve, and who is allowed to grieve.

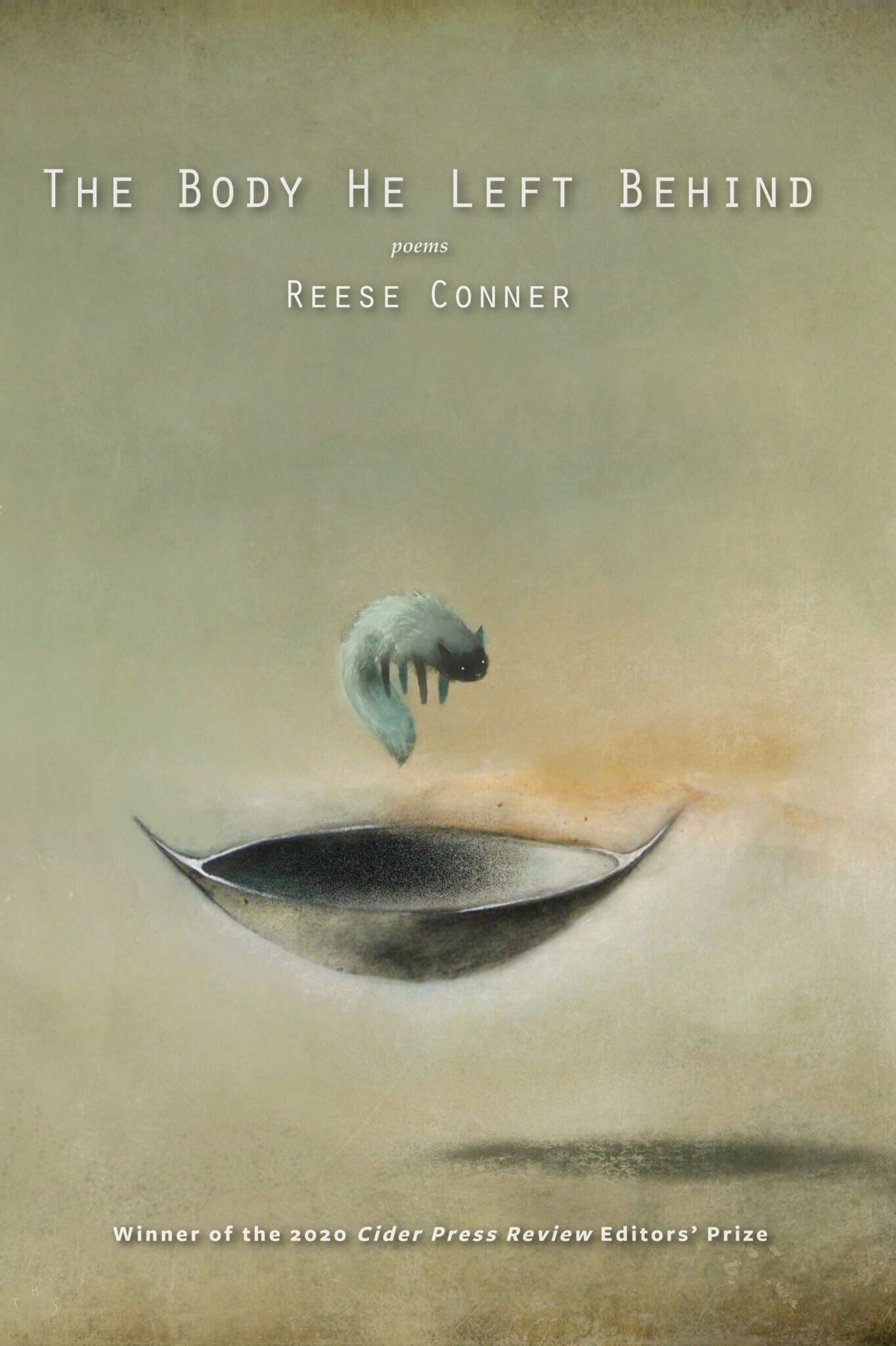

Reese Conner is a poet, teacher, and winner of the 2020 Cider Press Editors’ Prize Book Award for his debut poetry book, The Body He Left Behind. His work has appeared in Tin House, The Missouri Review, Ninth Letter, Barrelhouse, New Ohio Review, and elsewhere. His writing has received the Turner Prize from the Academy of American Poets and the Mabelle A. Lyon Poetry Award, and he has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Reese teaches composition and poetry workshops at Arizona State University.

I first met Reese in 2012 in Tempe, Arizona, where we were both incoming MFA Creative Writing students at Arizona State University. In the years since, I’ve been fortunate enough to have Reese, not only as a peer, but as a trivia teammate, Dungeons and Dragons comrade, and breakfast buddy. It has been a pleasure to see Reese grow as a poet in the time I’ve known him, to see his work become more biting, more introspective. I admire Reese’s ability to mix humor and earnestness, for his ability to look at what others want to turn away from. You can preorder The Body He Left Behind, a heartbreaking book of poems about cats, grief, and the ways we love, from Cider Press or your local bookstore.

*

Dana Diehl: We’ll start at the obvious place. What, for you, makes a cat such an enticing subject for a poem?

Reese Conner: Firstly, and I cannot stress this enough, I actually like cats. Let me tell you, actually liking cats did some hefty lifting when it came to writing a book chiefly about cats. The truth is I struggle mightily to simply start writing a poem, which I understand is a common issue for writers, so I don’t imagine myself unique. One way I found to combat that looming failure-to-launch was to shoehorn a cat into every piece I could because it created an immediate investment for me — I cared about the cat, so it made it easier for me to imagine the reader caring for the cat, too. That, in turn, made it easier for me to imagine the poem being successful and, therefore, worth writing.

Secondly, cats acted as vehicle to tackle some pretty big abstractions. For example, I was particularly interested in the ways we prepare for, encounter, and react to grief. The dying or death of a cat allowed for a general exploration of grief, yes, but it also led to questions about what we are allowed to grieve, how much we are allowed to grieve, and who is allowed to grieve. In one poem, “The Necessary,” I make this quite explicit by ranking griefs in order of importance. The point is not that an objective measurement of griefs coming from an external source is actually valuable, rather the point is that the ranking of griefs is a powerful, tacit thing that we already do. And that becomes wildly hurtful when one’s internal, subjective measurement of a grief does not align with where others think it ought to be. In particular, this comes into play with the father in the poems, who deeply loves his cat but does not feel comfortable mourning a cat on account of traditional masculinity. Come to think of it, exploring the effects of masculinity by way of a beloved cat is essentially the SparkNotes of my book. Even though I gave you the SparkNotes, I still hope you read it, though!

DD: I think there’s this fear that in writing about pets we risk being “cheesy” or overly sentimental. Is this something you actively tried to avoid while writing these poems? Or were there other challenges you felt you faced?

RC: Hmm…this is a really good question. I was certainly aware of the risk of sentimentality because I had been warned, but I guess I never really worried about it. In fact, I like to think that I purposefully approached the sentimental because, while it is often regarded as “cheesy” and lowbrow and not appropriate in a poem, there is a reason it is so ubiquitous, right? It speaks to shared experience. It must. We have Hallmark cards and abstractions because they resonate with just about everyone. And so, since the collective “we” has a penchant for getting overly sentimental about our pets, it seems pretty valuable to explore why. Pushing that further, it seems pretty valuable to explore why it is considered overly sentimental do so, especially if it is so common. Why is it that there is a perception that dead or dying pets should not be worth the grief we give them? I’ve certainly felt it — there is a guilt associated with mourning a pet so powerfully, and, in my experience, that guilt is a reaction to the idea that it is just a cat or just a dog, again referencing that unspoken hierarchy of griefs. In my book, I guess I wanted to legitimize mourning a pet so powerfully by exploring why the sentimentality makes sense and why we shouldn’t look down on it.

DD: Please tell us about the process of writing this collection. At what point did you know you had a book on your hands?

RC: I want to preface by making clear that I do not necessarily suggest the route I took because much of it was flailing about and generally having no idea about a great many things regarding publishing.

All right, so the one talent I know I have when it comes to writing is my ability to get lost in the weeds. I am consistently proud of my moment-to-moment choices within poems. You know, diction, line breaks, the particular idea I am trying to get at, etcetera? I’m proud of those. I really pay mind to have a rationale for each of those smaller choices in case the never-going-to-happen scenario of someone publicly holding me accountable for one such choice actually happens. This means that I am pretty confident in each poem I have written because I have the bandwidth to consider a full poem at a time. Unfortunately, that talent for the microscopic seems to have adversely affected my ability to see the big picture, which made organizing all my poems into a cohesive book quite the task.

And so, my process was mostly to lean into my talent and simply focus on each poem as a standalone. There was additional logic behind this approach because the idea of ever winning a book prize and publishing a book felt impossible, so it made sense to devote my attention to publishing individual poems. I didn’t really realize I had a book until I had enough poems to make a book. At that point, I took stock of what I was actually doing in my work as a whole.

All right, to be fair to myself, I may be being a bit misleading about how little I considered a book-length work. It’s not that I had never considered what my book might look like. For example, I knew, even as I was writing standalone poems, that fathers and cats and domesticity were through-lines for my work. I also knew exactly what the first and last poems in my book would be, and I knew the important poems that needed to go in-between in order to make the narrative work, but I had the vaguest idea of where those poems belonged. Essentially, I felt overwhelmed. When I had enough poems to meet book-prize criteria, I slapped together an iteration of my book that was significantly longer and less cohesive than what it is now. It also had a different title that I consider embarrassingly pretentious in hindsight: An Expectation of Broken Things.

Anyways, at this point, a wonderful friend and fellow writer, Melissa Goodrich, offered to slog through my mess and to help me out. I owe an incredible debt to her suggestions on ordering, cutting, and even the title of the book. Truly, I cannot overstate how integral Melissa’s involvement was in making my book what it is. You should absolutely check out her fiction and poetry because she’s not just an organizing maestro, she’s a damn good writer, too. When I read through my book as assembled by Melissa, I knew I had something to be proud of (and I knew I had someone to thank).

DD: In the first section of the book, there’s a focus on the physicality of the cat: old cat made of bird bone and balsa, broken rubber bands / heavy as ball bearings. However, as the book goes along, there’s a shift to the human body, as well. How are the body of the cat and the body of the boy connected for you?

RC: I guess those specific bodies are not terribly connected for me. Bodies, in general, were an important topic in the book, though. I wanted to really wrestle with the distinction (or lack thereof) between the body and the mind, which I know sounds like pseudo-philosophical bullshit, so we can roll our eyes together. Still, I recall a time when I was young where I honestly did not consider the two things as separate. That has changed. Now, when I define “me,” I am thinking of my mind primarily. And so, I am very interested in locating that last time when I hadn’t separated the two, when my body was “me” as much as anything else. Exploring that transition as well as exploring how we often define others as their bodies rather than their minds were important considerations when writing my book.

DD: This book takes a stark look at violence, as it is inflicted both by and on the subjects of these poems. The speaker loves his cats, while simultaneously observing their potential for brutality, their propensity to kill. The speaker begins to see violence in himself, as well.

I love this line from “I Was Innocent After All”: She told me / I had been good incorrectly […]

And this one, from “The Necessary”: To be clear, he is not a monster. / He simply decided that progress / meant putting things / where they do not belong […]

What do cats, or other animals, teach us about being a monster versus being innocent? Is it possible to be both at once?

RC: I think animals can teach us quite a bit about both monstrousness and innocence, particularly regarding the nuance of intentions mattering while concurrently not mattering at all. For example, in my poem “Like a Gift,” I address this head-on when the speaker is holding his cat to protect it from the neighbor’s dog. The cat recognizes the danger that the dog poses and would likely prefer to run away, so being arrested in the speaker’s arms probably doesn’t sit too well with the cat. And so, the poem posits that at some point the cat’s instinct to run from the dog becomes an instinct to run from the speaker, as well. This, in turn, poses the question of whether the speaker is correct to “save” the cat from its own instincts simply because the speaker has good intentions and the power to impose them. If the answer to that question seems simple and that the speaker was wholly in the right, then I would offer another set of questions regarding at what point the cat loses enough agency for the loss of agency to matter; at what point micromanaging the cat’s instinct becomes a trespass; and at what point the intention to save the cat from itself becomes monstrous. Obviously, I do not think there is an easy, blanket answer to these questions, which is why I do not offer one in the poem and why I won’t offer one here. What I do know is that many people seem to think good intentions earn a clear conscience, end stop. I believe that mindset can be incredibly dangerous and is often incredibly condescending, which is why it is something I address pretty heavily in my book.

DD: What are some other obsessions in your life right now? Do you find that they influence or inform your writing in any way?

RC: This is not a “right now” thing, but I have been obsessed with movies, television, and music for as long as I can remember. Each influences and informs my writing in powerful ways. In fact, I would say that my primary mode of experiencing stories is not through traditional reading but through those other modalities. I used to be pretty self-conscious about that because I felt like I couldn’t be a strong writer if reading traditional texts wasn’t my main source of reading. I do not think this is as widespread as it once was, but there is often an elitism when it comes to types of writing and, therefore, types of reading. I wholeheartedly disagree with it, but I’m sure you’ve heard this mantra: “Those who can’t write poetry, write short stories. Those who can’t write short stories, write novels. Those who can’t write novels, write screenplays.” I have heard that exact quote in multiple workshops throughout my career as a writer, and it always stung. I get it, though. Follow that proposed escalation in quality of writing and you essentially find the converse of who makes the most money from writing. Considering that, I can understand why some would want to believe in that hierarchy. After all, you’re not going to make much money from poetry, so it would be nice to believe that it is the purist expression of the lot. So, while I understand where the cliché comes from, I adamantly disagree with it and, more than that, think its utter bullshit. Good writing is good writing.

On a lighter note, I will offer one movie, television show, and song that helped inform some part of my book.

Movie: In Bruges.

Television show: Dollhouse.

Song: “Night Moves” by Bob Seger.

DD: If The Body He Left Behind had a soundtrack, what are a few songs that would be on that list?

RC: “Independence Day” by Bruce Springsteen. “As the World Caves In” by Matt Maltese. “Father and Son” by Yusuf / Cat Stevens. “Prison Trilogy (Billy Rose)” by Joan Baez. “Cat’s in the Cradle” by Harry Chapin. “Divorce Song” by Liz Phair.

DD: Finally, what advice do you have for emerging poets trying to finish or publish their first books?

RC: Well, I’m not sure if I have any advice on how to finish a first book other than to write it in a way that works for you and to take every bit of advice on how to write a book with just the biggest grain of salt. There are so many “truths” about what you need to do in order to be a writer and, while I think most of them are well-intentioned, they often serve to gatekeep who gets to be a “real” writer. As a wise interviewee once said: good writing is good writing.

As for publishing a first book, I do have some advice, and you may take it with whatever sized grain of salt you see fit: submit. Honestly, that’s it. I know so many ridiculously-talented writers who are too intimidated to submit, too afraid of rejection to submit, or who just don’t quite believe the mountain of failure that happens behind the scenes for just about every successful writer. If you are an emerging writer and you have conviction in your work, submit more than you think is necessary because that is what’s necessary. Get as comfortable as you can with rejection because, unfortunately, what you’ve heard is true: publishing is a numbers game.

Lastly, and this has nothing to do with finishing your own book or publishing your own book, but I’m going rouge with some unrelated advice: urge your own ridiculously-talented writer friends to submit, too. Be the good kind of envious when they succeed and support them as fully as they deserve.

Memory vs. Truth: a Review of Oliver’s Travels by Clifford Garstang

As Ollie develops Oliver’s character, anyone who has attended a freshman creative writing workshop will be amused to recognize the young writer trope of prosaic fantasy-fulfillment, the way a twenty year-old reveals their gushiest visions of their ideal selves, while casting love interests as props to their main character’s self-discovery.

All novels are mystery novels, a seasoned author tells hopeful writer, Ollie. At the core of everything we read about a character is their greatest desire. The mystery, as in real life, is what will the character do, and to what lengths will they go to attain this desire?

Ollie’s desire is multifold: his most urgent need is to find his Uncle Scotty, and ask him why Ollie is haunted by childhood memories related to him. Underneath this urge runs the very familiar, existential dread of the recently graduated. But in Ollie’s case, this includes the question of his sexuality. In Oliver’s Travels, Clifford Garstang interrogates the folly of memory and meaning through a deeply flawed, possibly traumatized, occasionally problematic main character, asking, how do we know a thing, or how do we come to accept something as known?

Oliver’s Travels is indeed about travel, including the travels Ollie should have taken; “I should have gone west, like the man said,” the novel opens. But rather than follow this romantic cliché of young adulthood, Ollie does what many young people are forced to: move back in with a parent. At first it is in Indianapolis, with his divorced father and “wounded warrior” brother, Q in the house where Ollie grew up. One day, Ollie is looking through family photographs when he becomes curious about his father’s estranged younger brother, Scotty. His father tells him Scotty is dead. His mother tells him Scotty is dead. Neither of his siblings, Q or Sally-Ann can recall what happened to him. But Ollie’s memories of his adventurous uncle, and his lack of memory of his death, point to different conclusions.

When staying with his father becomes unbearable, Ollie moves in with his mother in Virginia. Once again, he fails to go west. He admits, “I’m deficient in the courage department.” There Ollie accepts a job as an adjunct professor of English at a community college. He meets another teacher, a prim young lady wearing a cross necklace named, appropriately, Mary, whom Ollie begins half-heartedly dating. Immediately he begins projecting a version of himself that he suspects she wants: a passionate teacher, and a nice guy certain of his future.

But Ollie is anything but certain of his future. What will he do with a degree in Philosophy? He realizes he greatly misses the structure and challenge of school. He was inspired by his relationship with one professor in particular, which ended abruptly. Yet the influence of Professor Russell is clearly embedded in Ollie’s consciousness, as Ollie’s chronological narrative is interspersed with his memories of the professor’s lectures and their meditation sessions.

Meanwhile, Mary and Ollie are all wrong for each other. They disagree on nearly everything, with little crossover in interests and tastes, to a comical degree. Ollie is a wimp and Mary is a ninny. As such, their convergence only makes sense, the one too scared to leave the other, despite their obvious incompatibility. Mary, he thinks, represents things he should want: a nice, churchgoing girl who reads books (albeit not “good” ones), plays piano, sings “like a Siren,” and knows she wants to be a teacher, a wife and a mother. She has also continued living with her parents for three years after graduation, a thought that is mortifying to Ollie. But when he meets her brother, Mike, suddenly Ollie wants to spend as much time with Mary as possible. Why can he not get him out of his mind, Ollie wonders? And does it have to do with his patchy memories of Uncle Scotty?

Since cowardice and indecision render him incapable of running the trodden path of young male fortune-seekers, Ollie lives out his fantasies another way: on the page. He invents “Oliver,” an alter-ego who possesses the adventurous spirit Ollie lacks, journeying to distant lands with an “exotic” woman by his side. As Ollie develops Oliver’s character, anyone who has attended a freshman creative writing workshop will be amused to recognize the young writer trope of prosaic fantasy-fulfillment, the way a twenty year-old reveals their gushiest visions of their ideal selves, while casting love interests as props to their main character’s self-discovery. With characters’ names barely changed from their counterparts (“Oliver” and “Maria”), Ollie re-imagines himself as charming and courageous, and Mary as exciting and dangerous. It is at times agonizing (read: triggering) to watch as a scared young man wastes an ambitious young woman’s time, abusing her trust while he figures himself out. And yet Mary may have a secret or two of her own. Meanwhile, the possibility of his childhood trauma looms heavily over Ollie. We are beckoned, if not compelled, to give him a break.

Ollie’s relationship with his father is especially pertinent to his wavering confidence. Ollie was born with only four toes on each foot, a harmless expression of some genetic trait. “One of the clearest memories I have of my childhood,” Ollie recalls, “is my father’s insistence that I wear something on my feet while in his presence–socks, shoes, slippers.” When one day young Ollie compares his number of toes to his brother’s, he finally notices the discrepancy and begins to cry. “But it wasn’t the missing toes I was crying about. I had finally understood why my father hated me.” Reading Ollie as a possibly-not-heterosexual character, this strikes an especially emotional note, as he realizes his father hates him not for his choices, but for the way he was born.

As snippets of his childhood return to Ollie, he wrestles with the imperfect and erratic nature of memory and truth. If others have no memory of an event, and your own is patchy, did it happen to you at all?