Say Yes: An Interview with Lindsay Hunter

Don’t Kiss Me, Lindsay Hunter’s stunning second story collection, is a negative imperative: at once a warning and a challenge. With its title and vaguely menacing cover (a tube of red lipstick nestled between glimmering, dagger-sharp letters), the book lures readers in and then dares them to resist.

Don’t Kiss Me, Lindsay Hunter’s stunning second story collection, is a negative imperative: at once a warning and a challenge. With its title and vaguely menacing cover (a tube of red lipstick nestled between glimmering, dagger-sharp letters), the book lures readers in and then dares them to resist.

Similarly, the twenty-six stories inside Don’t Kiss Me attract and repel. Hunter’s characters are women who kiss their much older teachers and lust inappropriately after nine-year-olds. They take terrible advice, they stay with abusive men, they overeat, and they accumulate far, far too many cats. Hunter presents her readers with humiliating, demoralizing, hopeless-seeming situations, and challenges us, in the midst of it all, to laugh at the jokes, connect with her characters, and appreciate every little glimmer of hope.

As with her stories, there is, refreshingly, no pretense with Lindsay Hunter. Her twitter feed is a dizzying, hilarious string of self-deprecating jokes and confessions. Her blog is a mix of meaningful ruminations on writing and gender roles, pictures of her beautiful baby, and fart videos. She is every bit as eccentric, entertaining, and irresistible as her writing. I was delighted to have the opportunity to chat with Lindsay over email, and to hear her thoughts on reading aloud in public, keeping friends at the dog park, and being grateful for the writing life, even when it keeps her up at night with a pounding heart.

*

Liz Wyckoff: First, Don’t Kiss Me is a killer book title. And the cover design is such a nice complement: there’s a toughness, a sharpness to the book, but also something kind of inviting. Was it hard to choose the title, or did this one speak to you right from the get-go?

Lindsay Hunter: It was very hard! I went around and around. Initially it was going to be called Trash/Treasure. As in, “One man’s trash is another man’s treasure.” But my husband was like, “That’s real easy fodder for the critics.” Ha! Then I wanted to call it All Them Skies because the sky is in basically every story, and I’ve gotten shit for using the sky so much, and I kind of wanted to be in your face about it. But that didn’t seem to fit either. I always really loved the threat and challenge of Don’t Kiss Me, which was the title of the final story in the book, and I realized it was the perfect title for the book as a whole, which to me is like you said—tough and sharp but desperately, desperately inviting.

Liz Wyckoff: In what ways does this collection feel different to you, as compared to your first collection, Daddy’s?

Lindsay Hunter: It feels more sure of itself. Maybe because it’s my second book, and not my first, and so I’m projecting those feelings onto it? But there was a special kind of self-torture in putting my first book out; I remember being convinced that everyone would hate it, and then I had to ask myself why I’d put something I was convinced would be hated out there. I had to come to terms with it being mine, and trust that even if it was hated, I loved it, and that was enough. So I had all of those battle scars in me when Don’t Kiss Me became a thing, and I had become more sure of the stories I wanted to tell, of the “mineness” of them. And it was like a maturing for me, much in the way that the stories in Don’t Kiss Me feel more set in adulthood, while those in Daddy’s feel set in adolescence.

Liz Wyckoff: Many of the stories in Don’t Kiss Me are written in the first person, narrated by women who are really struggling—to overcome fears and loneliness, to make sense of awful things they have done or awful things that have happened to them, to pull themselves up out of some pretty mucky situations. These women are unquestionably unique, but they occasionally share a similar outlook or sense of the world. How do you go about inhabiting these characters?

Lindsay Hunter: I usually hear a sentence they’re saying, and I’ll write that down, and their voice kind of reveals itself to me as I go. Like it’s already there and I’m just kind of brushing away the debris hiding it. I just learned that Elmore Leonard said something like “if it sounds like writing, I rewrite” and YES to that. I want it to feel like life. Ha! As if that’s some kind of revelatory statement for a writer to make. But it’s nonetheless true.

Liz Wyckoff: I’m interested in the rules that govern your stories—what I’ve heard Kevin Brockmeier describe as “ground rules.” For example, “Three Things You Should Know About Peggy Paula” is arranged into three long paragraphs describing the three things we should know. And the narrator of “Like” inserts the word like into almost every one of her sentences. Do you consciously set constraints like this when writing?

Lindsay Hunter: I do, sometimes! Not always before I sit down to write. But as I’m going these constraints I’m suddenly following become clear. With “Like,” I wanted to show how the way these girls were talking simultaneously removed them from reality while also revealing it to observers. Like, like, like. Instead of “is” or what have you. With “Three Things You Should Know About Peggy Paula,” I think I originally set out to just write a series of random facts about Peggy Paula, and it became three essential things.

I will say that, as the former co-host of a reading series where everything had to be under four minutes, I’m very used to writing stories that fit within that time constraint, so that might be one I set unconsciously for myself.

Liz Wyckoff: I just read a really rollicking conversation between you and Alissa Nutting on the FSG Originals website in which you two talk about “gross stuff.” You (and Alissa, too) seem to be really comfortable with the grossness in your work—the barf, snot, turds, and farts that make an appearance in almost all of your stories. Was there ever a time when you were less comfortable with it, or anxious about what readers might think?

Lindsay Hunter: I think, actually, I kind of blindly assumed people wouldn’t be so shocked by it. I remember writing “The Fence” in an afternoon and reading it to my class the next day, very excitedly, and looking up to see people looking kind of choked by their collars. I’ve always been the type of person to want to just get past politeness or artifice, and the way I do that in my personal life is to immediately start talking about all that “gross stuff,” which, to me, is an essential part of life. But yes. Now I’m anxious about people’s reactions, now that I fully understand how shocking some of this stuff is to people. Like when my dog park friends wanted to read Don’t Kiss Me, I felt sad, like, “Well, there go our evenings at the dog park.” (But happily I was wrong!)

Liz Wyckoff: Has your relationship to readers, or that vague idea of “audience,” changed over time?

Lindsay Hunter: Definitely. Well, maybe it’s more that I go back and forth between kind of nervously hoping what I’m writing will land well and writing toward an audience that’s cheering me on. It depends how strong I’m feeling on that particular day.

Liz Wyckoff: Speaking of writing for an audience, as you mentioned earlier, you’re a co-founder of Quickies!—a bi-monthly reading series in Chicago. What does reading (specifically your own work, aloud, in public) mean to you as a writer?

Lindsay Hunter: It means everything! I encourage all writers to read their finished stories aloud to themselves, a partner, an audience at a reading, whatever you can get. It reveals so much. Forming the words in your mouth is a different thing than typing them onto a page. For me, it helped me take ownership of both my physical voice and my writing voice. I needed reading practice badly, and Quickies! gave me that, and it gave me a slightly buzzed audience who were all mostly listening.

Liz Wyckoff: Interacting with other writers seems to be a pretty big part of your life. Do you find that there are good and bad things about surrounding yourself with writer friends?

Lindsay Hunter: A professor once told us we should say “Yes” to everything, because it would open up so many other opportunities for us. I took that to heart and began saying “Yes” to reading at my friends’ reading series, writing stories for their journals, going on tour, doing interviews, etc. Before I knew it I was part of something. That professor was so right! Being a part of a writing community keeps me involved, challenged, aware, all of which, if you want to forge any kind of writing career, is so important, and so easily lost.

The bad part about being part of this community is all the envy and self-doubt and constant comparing. It’s a very dangerous place to find yourself, but I think every writer goes through it. “Shit, this guy wrote two novels in a year AND publishes a story like every week. I watched Breaking Bad all weekend and wrote a single tweet. Therefore I am worthless!” You have to live the life you want to live, and celebrate that. Part of that life is being surrounded by incredibly talented people, so let yourself celebrate them, too.

Liz Wyckoff: I was really moved by one of your recent blog posts called Real Talk. In it, you discuss your decision to become a writer, the importance of showing gratitude, and the recurring theme of trying. You describe the decade between your initial decision to start writing and the publication of your first book as a decade “full of love and travel and fear and doubt and tries and tries and tries.” It sounds so simple, but I think trying can be really terrifying! Do you feel terrified, too, sometimes?

Lindsay Hunter: Always! Just last night I laid in bed, wide awake, even though I have a cold and I’m exhausted and there’s no telling when my son will wake up, so I should have been sleeping, but I couldn’t. I was filled with terror about my novel, and what comes after, which I in no way can see clearly. But if someone had said to me in January 2000, when I decided to focus on writing, “Hey, guess what, it’s going to be an entire decade before you get a book published,” I would have been paralyzed. So you just keep pushing through. You keep living your life, loving the people in it, being grateful for all of it, all of it, instead of worrying about what you don’t have or what you don’t know. Sometimes it’s easier said than done and you find yourself listening to your husband and child and dog snore the night away while your heart pounds itself to a pulp. But you try.

Liz Wyckoff: You’re writing a novel! Other than keeping you awake with a pounding heart, how’s it going?

Lindsay Hunter: It’s going! But there is that issue of having time, which I don’t have enough of these days. So I fear my novel will suffer because of it. Like a neglected child. Still a child, but something is off. I just keep telling myself, Well, it HAS TO BE FINISHED AT SOME POINT. And on that day I shall drink the largest goblet of Sauvignon Blanc the world has ever seen.

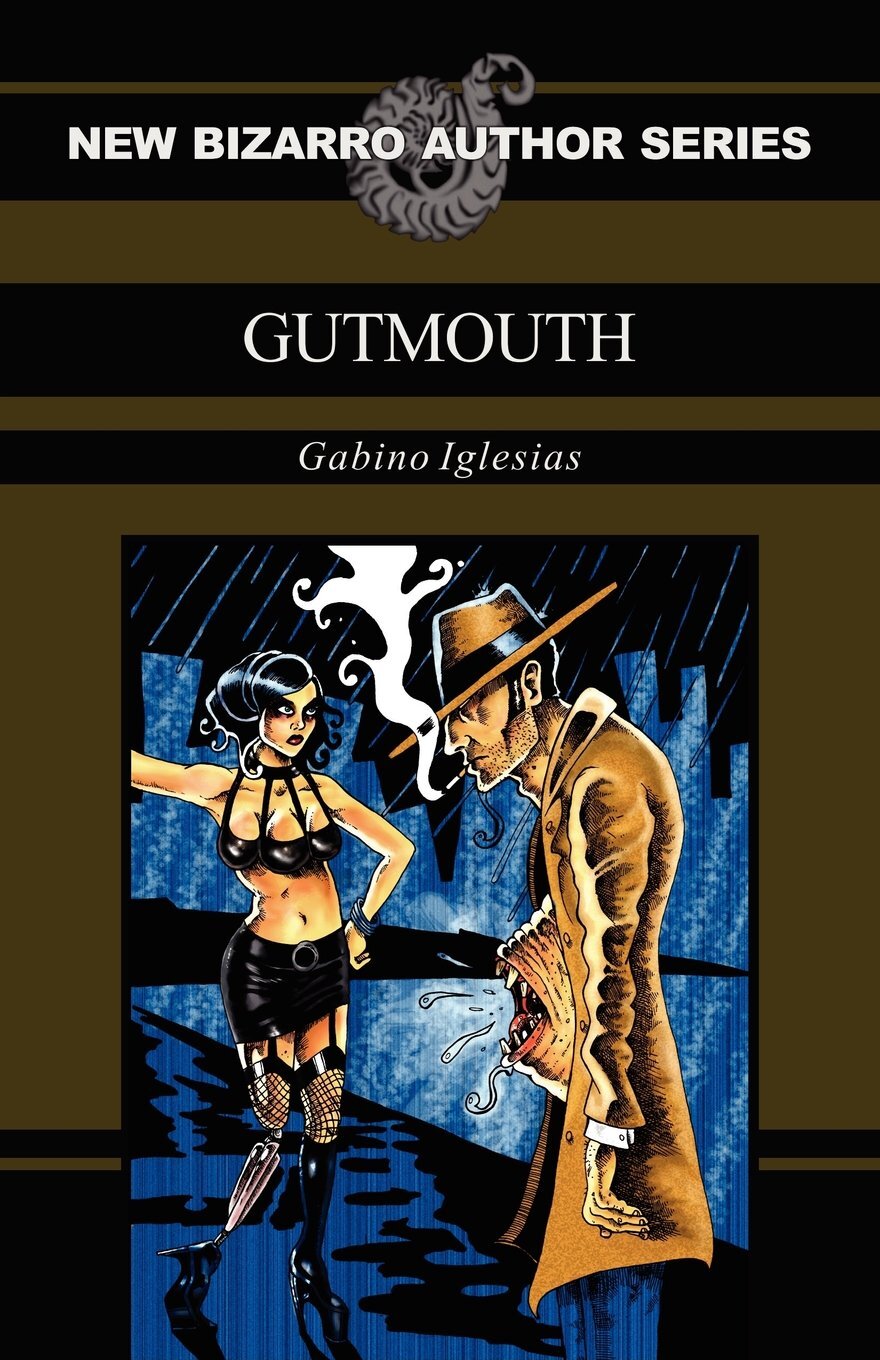

Defying Genre and Categorization As It Scoffs At Attempts At Civility: On Gabino Iglesias's Gutmouth

Considering how Iglesias ups the WTF factor (I’m sorry, but there’s no other word to describe it) with every chapter, I wouldn’t be surprised if in future works, he punts the bizarro to another stratosphere.

I haven’t read much bizarro fiction so I had no idea what to expect when I picked up Gutmouth by Gabino Iglesias. Expectations were shattered as the book was wilder than I could have imagined. Told in first-person, this is a visceral, intense read that grips you by the throat, defying genre and categorization just as much as it scoffs at any attempts at civility. There is a mouth called Philippe growing out of Dedmon’s stomach, a literal “gut mouth,” that poses an odd contrast with his fine tastes and British accent. As strange as that may seem, the world is even more twisted.

I looked up at the dark sky. Huge artificial asses hung from extension poles on top of every lamppost. The asses had been installed as method of crowd control when the New World transition began. The devices were designed to rain down acid diarrhea. Kind of like a postmodern version of a lachrymatory agent with an olfactory punch.

Olfactory punches abound and you will need to lift up your mental defenses as they will get bloodied and bruised by the barrage Iglesias volleys at readers. Dedmon was a repo man before MegaCorp took over the world and enlisted his skills to become a hunter. He tracks down “criminals” whose infractions against consumerism include not buying enough allotted products and “stubborn citizens who wanted to grow their own food.” Their punishment is inhumanly severe and even though MegaCorp “enjoyed using death row inmates as guinea pigs for new products,” there is an almost sociopathic apathy to Dedmon as he arrests the perpetrators without empathy. The combined Mr. Dedmon and Philippe are a misogynistic and misanthropic pair, brutes in every sense of the word. Satire and horror feed off each other, racing to chapter’s end with an absurdity that would make Kafka seem tame (and this despite the kleptomaniac roaches). Iglesias makes no attempt at being politically correct, but instead embraces the world with all its dark gory brutality. The implication is that since everything is commoditized, morality is tossed aside or at least distorted to an unrecognizable norm. Easily offended readers will find themselves turned off by some of the caustic exchanges as well as the expletives. But if you can see beyond it, then the societal criticisms and attitudes implicit in such a world provoke deeper questions. Take for example the medical technology that is so advanced, it allows for the reversal of pleasure and pain along with limb growth (spurred by salamandar DNA). The rampant genetic testing in part results in a pimple on Dedmon’s stomach that expands into the eponymous mouth. At the same time, it is also a parable for the modern man, torn into hundreds of different directions and driven by insatiable hunger and perpetual discontent. As though that weren’t bad enough, enter the love, or lust, of his life:

She wore a bologna bikini and a Viking hat. The thin slices of fake meat barely covered the nipples on each of her three breasts. Her skin glistened like a wet olive… By the time Marie was done jumping with her slimy stump buried deep inside the convulsing fat monster on the strength, I knew I had found the love of my life.

Dedmon’s conflict transfigures into a mutation of the traditional skew on dualism that is neither a Cartesian split, nor Hegelian dialectics, but instead, a mouth (Phillipe) that sticks his tongue inside Marie’s genitalia to arouse her, in turn arousing a vicious jealousy in the brain (Dedmon) that incites him to murder. In other words, the most fucked up love triangle I’ve read, seen, or heard to date. Shed the squid guards, the rat friend, the Genital Mutilation and Erotic Maiming Center, and a world torn apart by steroidal madness, and the bizarre is rendered in sympathetic flashes. Dedmon is just a poor bum in love with the wrong woman.

Without having breakfast, I got my clothes and shoes from the safe, dress and left. My feet carried me straight south to Shlicker Park. I sat on a beach, eyes still blurry with drink, heart broken and senses reeling. For the next few hours, I sat and watched the serpent-trees snag bloated pigeons in mid-air. The crunching of their tiny bones mixed with the frantic cooing from the survivors to create a perfect melody for a Saturday morning in the park.

Considering how Iglesias ups the WTF factor (I’m sorry, but there’s no other word to describe it) with every chapter, I wouldn’t be surprised if in future works, he punts the bizarro to another stratosphere. For now, I wonder if there is a secret mouth under Gabino Iglesias’s stomach that he is hiding from the rest of the world. I wonder what it will spew if given free rein. I hope it is not too hungry. I don’t want to be eaten.

Even This, Even All of It, You Must Love: A Review of Micheline Aharonian Marcom's A Brief Hisory of Yes

A love story told backward, the end of it. August to August. Dry, bloodless heat.

A love story told backward, the end of it. August to August. Dry, bloodless heat.

A Brief History of Yes by Micheline Aharonian Marcom tells the story of the end of an affair. He is a blond, blue-eyed American man and she is dark-haired, Portuguese-born. In her, she carries the memory of the city where she was born, near the Targus River in her native land; and of her father, full of rage and violence. And of her marriage to a man with whom she had a son. She left him, in the end. But now it is she who is left.

“Maria, you are not right for me,” he says.

“We were not good for each other,” is what he said. The first man who broke my heart. He had taken the train down to my apartment. He had slept in my narrow bed while I sat up awake all night.

This was long after it had ended. He was trying to make me understand something I did not.

I did not ask him anything more. I nodded as if the logic was clear, as though even a child would understand.

“It’s not that I didn’t love you,” he said as we climbed the stairs to the train station platform. “It was never that.”

And then he was gone.

My mother was born to Portuguese parents, her father from Lisbon, her mother an island girl – San Miguel in the North Atlantic Sea.

For a year, I took lessons in Portuguese language, the rounded guttural sounds gravelly and heavy on my tongue.

I remember those months as a kind of weight pressing down on me. A dimly-lit classroom in the afternoon. Fluorescent light. Struggling with unfamiliar phrases that carried nothing of my own history, Korean-born adoptee that I was.

But dutiful. Obedient. Well-trained. I waited for my mother on the concrete steps in front of the school building. In the car, I would recite the day’s lesson. Haltingly I might say in Portuguese: “In summer, the ships leave port. In winter, the men return.

“Let me tell you a story,” Maria says to him, “of a girl a boy who meet up on the California coast where the girl dreamed him up, dreamed him up.” “You dreamed me?” he asks. “Yes. I called to you, first to the full moon on the bluffs at Salt Point where I sometimes go when I am sad and sit there, then to you, and you arrived.”

There is a Portuguese musical tradition called Fado. It is steeped in sadness. My mother took me to a restaurant one evening when she thought I was old enough.

Dark room. Velvet drapes. A low stage where a woman stood at a microphone while a man sat to her left, playing guitar. She wore a red blossom in her hair. Her voice was warm and low and filled the room with its vibrations. Old men sat at tables near the stage. Some wiped their eyes.

I sat across the table from my mother. Her hair long and brown. Her face turned to the stage.

On the ride home, she said: “I thought I loved your father. Maybe I did. I thought I knew. I thought if love was real, I would know.” And then she was quiet.

I had not yet met the man who would first break my heart. I was a blank sheet of paper on which the vagaries of love had yet to be written.

Maria has an old friend she speaks to on the telephone. After her divorce, he tells her, “Maria, you most open your heart. . . . There is no joy otherwise.”

Later, she asks him, “How do you tell, how can you, the truth of love from the illusions of it?”

When I met him, the sun was shining. It was summer. We were cast in the same play, a production of West Side Story. Although his hair was dark, he was fair-skinned. He was a “Jet.” And me, dark-haired, dark-skinned, I was a “Shark.” A dancing girl. Night after night, I painted my lips red, thrust my hips out and danced.

In the hallways of the empty school where we rehearsed. In the wings behind the stage. In the parking lot late into the night.

When it is over, Maria drives north to Salt Point where she walks the rocky cliffs and imagines, fleetingly, throwing herself against the rocks, or diving into the sea below:

Hello despair, she does not say (only the next day when others ask her of her holiday and she begins to weep).

Hello sea, air, sky, and black cormorants.

There is nothing good today in my heart. All is lost, all forsaken. My son with his father and the horsy faced girl. Me on these bluffs one-hundred-and-fifty miles from a city which is not my natal city, Pai gone, my uncles aunts cousins across the Atlantic in an old small inconsequential country where my old memories were made. I loved a tall, blond, blue-eyed American man; eventually he did not love me back. Looks again at the sea. Looks again at the sky. Lies next to the bush and would like to be the bush, the sky, the sea, seaweed, and cold autumn air.

It stretched on for years. There were others, between. But he was like a place I remembered from my youth and returned to again and again, recognizable. He was the path behind my childhood home that led to a broad ancient oak. He was the cool Atlantic waters that rose to meet me in long summer days. Something in him familiar and knowable to something in me. The way you might know that you will love someone even though you have only just met. And that it will not matter how long they love you, or how well. You know they will enter you, take root. That they will reside there, graft themselves onto your heart.

When it ended, it was in autumn. He was moving to New York. I did not yet know that this would be the end. I did not yet know that he would choose the dark-skinned, dark-haired woman he had loved for years. The woman alongside whom I had loved him in parallel. I did not yet know that he would take her with him to the rocky California coast. That would come later.

We spent the afternoon in his bed, the windows thrown open, the cool breeze chilling us. The leaves were turning and falling. In the distance, the wide Charles River flowed past. As night fell, I rode the bus home.

My mother’s mother was engaged to be married to an island boy who worked the sea. My mother’s father came to the island from the city and “the next thing anyone knew,” my mother would say, “they were coming to New Bedford.” City boy and island girl.

When she died, after fifty years of marriage, he followed soon after. As the story goes he said, “What is my life without my love?”

Her lover has a wound across his chest. A concavity where the bones did not form properly.

“It’s what you don’t understand,” she tells him, “how the wounds can be an opening.”

“In Portuguese, we have a word: saudade. In English you don’t have this word, and there is no accurate translation of it. Is it nostalgia? Or yearning for the absent one? Or the love that remains after the beloved has gone? All of this could be saudade.”

But he does not want to speak of love or yearning. He wants to go out. He tells her there is something playing at the cinema. And shouldn’t they go out. And she says Yes.

—

When it ended, I thought I could not bear it. That surely, the weight of his absence was enough in itself to crush the life from me, to break me, starting with my fragile heart.

But didn’t my stubborn heart surprise me with its resilience? Even as I lie there in my bed, willing it to stop beating?

I did not yet understand that love contains its end as life does. I did not yet know.

the absence created by the end of a love affair is another form of presence. And memory sings it, and singing it the blond blue-eyed lover returns. “Hello,” Maria says to him, “estou com saudades tuas.” And he, “Hello, Maria, I am here,” while he arrives departs arrives again until all things eventually arrive at their end.

And I did not yet know that a wound can be an opening. And that if one is to love life (and what is there to do but to love it?) one must also love these wounds, these openings, unbearable though we bear them.

Even watching as the train pulls away from the station. Even the rocky cliffs that lead down to the cold sea. Even the dying leaves of trees. Even one’s own stupid heart that knows no better than to keep beating, even as it is breaking. Ever breaking.

Even this, even all of it, you must love.

An Interview with Joseph Michael Owens

I think Shenanigans! provides a little slice of slice-of-life writing. It’s almost like an appetizer sampler platter. You sort of get a taste of the various things that take place in a couple characters’ day-to-day lives that may seem uninteresting at first but becomes interesting (I hope) by humanizing them in a relatable way; but at the same time, you also never spend too much time on one thing in order to prevent it (again, I hope) from getting boring.

Recently, I’ve had the wonderful opportunity to read Joseph Michael Owens’s short story collection Shenanigans! and I must say that I’m really into his style! For those of you who don’t know, Joe is also the Web Content Manager here at the Lit Pub, and once I had read his work, I was really happy to know that I was working with some highly talented writers here. Joe was very gracious in his allowing me to interview him, and his intelligence and generosity definitely shine through in his writing and in his discussion with me.

I hope you all enjoy learning about Joe as much as I did!

Sam Song: It was a pleasure to read Shenanigans! What were your major inspirations for writing this piece?

Joseph Michael Owens: Shenanigans! was a collection that began its life as my MFA thesis and turned into something more. The inspirations are probably too many to count, but the most prominent books that influenced it were Nicholson Baker’s The Mezzanine, David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, and Joshua Ferris’s Then We Came to the End. These books all have the ability to sort of charm their readers with closely examining what’s happening in their characters’ lives. I think Shenanigans! provides a little slice of slice-of-life writing. It’s almost like an appetizer sampler platter. You sort of get a taste of the various things that take place in a couple characters’ day-to-day lives that may seem uninteresting at first but becomes interesting (I hope) by humanizing them in a relatable way; but at the same time, you also never spend too much time on one thing in order to prevent it (again, I hope) from getting boring.

SS: What were some of the influences for Ben’s and Anna’s characters? Do you know people like them in real life?

JMO: Half of the answer is likely predictable; the other half might not be. Originally, the characters were actually based on Jennifer, the woman who I’d eventually marry, and I. However, I saw a lot of potential in other couples whose relationships I admired, as well as stories I’d read with characters who were genuinely likable. I feel like there is so much fiction being written right now where characters are either unlikable or unrelatable (by design) that I thought it might be fun to give a glimpse into people’s lives where the worst things that were happening were trivial, mundane things. Eventually, the characters became less and less Jenni and I and more themselves, which I loved. I’m leaving it up to the readers to figure out which parts are based on real events and which are completely made up.

SS: Why did you have what happened to Ben happen? For instance, why did you make Ben bike up a freezing cold mountain or have him spill scalding coffee all over himself?

JMO: One of those events may or may not have happened to either me or someone I know. I think with Ben’s bike ride up the mountain, it was sort of a way to show how people can do these amazing things when they don’t know they aren’t supposed to be able to. Ben basically sets off riding a distance he’s probably covered many times but isn’t really thinking about the fact that it’s nearly all uphill, which, having ridden a bike my fair share of miles, I can tell you, there is a big difference. He dresses for the weather at the base of the mountain, not considering how cold it’s going to be at the top. He just knows he wants to ride up the damn thing and so he does it. It’s only later he realizes that it isn’t the easiest thing in the world to “just do.”

The coffee story is, in some ways, an homage to shows like The Office and movies like Office Space. A fun fact is that the story is actually the first chapter of a novel I’ve been working on set in the same office with the same characters. Now that it was published in Shenanigans!, it might get cut from the final draft, but there’s certainly going to be more of Ben and Anna because why not, right? I really think the coffee scene is mostly indicative of the chaos and insanity that sort of defines most professional office settings. I work/have worked in them since I was eighteen, and this just seems like something that could (basically) happen. People are rushing around; the break-rooms and kitchens are often small but see heavy traffic; it’s the minutia of the day that really tends to get under people’s skin. I just set out with the hopes of recreating a sense of that.

SS: Is the idea of “just doing” an aspect present in other chapters in Shenanigans! as well?

JMO: If not for the characters, then it definitely is for the writing part. For example, “We Always Trust Each Other…” and “Ninjas! . . . (In the Suburbs?)” were both stories I started sketching out with no real idea of what they’d be or even if they’d be anything at all. One thing I really like to do is include free associations in my writing. I think the finished product stays a step or two short of becoming fully absurdist — e.g. in the vein of Mark Leyner or Jon Konrath — but it allows me to sort of take things to their strangest- and most extreme conclusions (i.e. ones that could feasibly happen).

SS: It seems pretty clear that Ben indeed cherishes his dogs. Why did you decide to let dogs be a huge part of his life? Are you a dog person yourself?

JMO: One thing I can say is that the dogs in the book were based on real life. I’ve always had dogs. Right now, Jenni and I have four total, but we’ve had as many as five. I thought it might be kind of fun to have a couple who don’t have kids but instead, a rowdy pack of dogs that keep them more than busy. We’re animal lovers, in general. I think it’d be hard to write a book without having some furry companions in it.

SS: Continuing the topic on Ben’s and Anna’s dogs, I notice that you even give them distinct “voices” and personalities. Mish and Brock are notable examples, in that they “speak” directly to Ben. Can you elaborate as to what this reveals about Ben’s relationship with them?

JMO: Dogs are so hilarious. I’ve always sort of had different voices for dogs in my head based on their mannerisms and expressions. It’s easy to forget that they aren’t actually human and responding in that way. I think this is something a number of people probably also do, but it adds an element that is new or weird to readers who perhaps aren’t “animal people.” That being said, non-animal people would probably get annoyed with the number of times dogs or horses or wildlife appear in my stories.

SS: Boxcars and Bomb Pops is different from the other chapters in that it isn’t so much about Ben’s present experience as it is about his flow of thought. In this chapter, Ben arrives at this epiphany that in society, “there is something wrong with or different about them if they find themselves not wanting, if they find things and stuff somehow unappealing”. What moved you to acknowledge this idea? Are these your own thoughts, someone else’s, or ones you fabricated for Ben’s introspective character?

JMO: There is this sort of unsaid and overarching idea in the book that people are (of course) incredibly multi-faceted and even go as far as to have different voices, depending on the situation they find themselves in. Ben is kind of a goof, but he’s also hyper-analytical at work as well as kind of introspective in ways that many of those that know him perhaps don’t recognize when he’s by himself. Ultimately, I think, when people are all alone and spending time with their thoughts, everyone is introspective. I liken it to wizened older people who don’t talk a lot but say almost profound things when they do talk; people who might not have a formal education, but are more in touch with the way things work than “book smart” people who’ve never really experienced much of the world outside of a classroom. These are two extreme examples of course, but the idea is that people are smart, in general, especially when they are allowed to sit down and just think about things outside of the hubbub of society.

SS: Do you yourself perceive this idea to be true?

JMO: I think it was something I first noticed in myself, certainly. It seems like when it comes to wanting something, the process of wanting is the driving factor, not actually acquiring the thing was that was wanted. This is really evident in hobbies that involve a lot of tinkering. When the project is finished that someone spent “X” amount of time tinkering with or upgrading or modifying, the person usually moves on to a new project. There are even commercials now about upgrading cell phones before the typical two years a person waits between new phones because there is always something newer and shinier on the market or just around the corner. All of this isn’t really what’s surprising. What’s surprising is that we really don’t like our bleeding edge device (e.g.) being rolled out with planned obsolescence in mind. (But that’s just my two cents.)

SS: The final and arguably most complex short story of Shenanigans! is The Year that Was…And Was Not. So much happens in this chapter, and instead of merely a glimpse at a moment in Ben’s life, we are presented with a dire prospect of his future. Why did you decide to make this chapter such an emotional roller-coaster for Ben and his family and Anna? Why the interplay of the good and the bad?

JMO: A lot of the motivation behind the last chapter was selfishness on my part. It was kind of my way of not wanting to let go of the characters, so rather than have everything tidied up in a nice complete package, I wanted to show that the young couple still had most of their lives together ahead of them. Life is a bit of an emotional roller coaster, regardless of how exciting a person’s life is – or is perceived to be, and nothing is either 100 percent terrible or 100 percent awesome. What is a huge crisis to some of us may seem like no big deal to others. Ultimately, we’re all just here on the planet trying to do the best we can within the situation(s) we find ourselves.

SS: I’ll end my questions about the plot of Shenanigans! here; I don’t want to spoil it for all the lovely people at The Lit Pub! Why don’t you share with us some of your upcoming projects?

JMO: I’m currently working on two very different novels. One is a sort of spin-off of Ben’s character in Shenanigans! called Human Services where it focuses on the people who work at The Agency and all of the insanity that occurs in a professional office setting. I would say it’s pretty much solidly in the literary fiction camp.

The other thing I’m working on is a project I’ve been kicking around in my mind for a few years now, which is a sort of literary epic sci-fi/fantasy novel tentatively called “Of Gods and Men.” I grew up reading lots of sci-fi and fantasy — especially the latter — and always kind of wanted to do something in the genre that inspired me to be a writer. It wasn’t until recently, with the popularity of the A Song and Ice and Fire series (aka Game of Thrones) that I sort of realized that this was a viable option for me. That is to say, I’d really been wanting to use the skills I’d picked up writing literary fiction the past seven or eight years and apply it to something more genre related. Perhaps the work most responsible for this epiphany, even more so than Game of Thrones, is M. John Harrison’s unbelievably impressive Viriconium omnibus. The prose is awe-inspiring and the way he includes elements of surrealism and bits of magical realism is something I can’t begin to do justice here. You’d simply have to read it yourself.

SS: Is there a particular writing process you go through?

JMO: My process is pretty un-process like. I’ve got severe ADD, so it’s almost impossible for me to get into anything that resembles a regular writing schedule. I basically write when I can and/or when I’ve got an idea that’s begging to be put down on paper. Though when I do, I typically draft longhand first; it’s always been that way for me. I find it easier to compose with a pen than I do with a keyboard. Then I’ll type out a first draft, print that draft, and proceed to edit the printed copy with a pen. I know there are a lot of steps, but this has always been the best method for me, personally. There seems to be a number of established writers who do this too, so I don’t feel quite so weird about it. I feel like I could probably write more if I decided to skip the longhand and type everything — editing it solely within the word processing app — but my current method feels to me like what I do write is better; quality over quantity!

SS: People have often told me that if I want to write, I must first ask myself why I want to write. So, Joe, why do you write?

JMO: I think a lot of people describe their reasons in terms of zen sayings or for their sanity or they profoundly muse on their destiny or life’s calling as writers, but for me it’s really so much simpler than that: I just really like to do it! Admittedly, I feel bad — or maybe guilty is the right word — sometimes when I don’t write, but there can be significant gaps in my output during a given year. I think I feel worse because I know it’s easier to stay in a kind of writing flow than try to repeatedly build your momentum back up, but it also comes down to your own personal capacity: write as much as you can within the amount of time you feel like you want to spend doing it.

SS: What advice do you have for aspiring writers?

JMO: Part of this can probably apply here, but the most important thing people who are aspiring writers can do is read as much as they can. Stephen King said you have to read a lot to write well, and I think that still holds true. I think it’s especially important to read books you like, which may seem obvious, but often students will get bogged down reading stuff they are assigned to read or reading stuff they’ve been told they should like. I’m sorry to say, but not everyone is going to love reading Faulkner (e.g.), especially if their style is more similar to, say, Barry Hannah, to compare two Southern writers. Maybe you’d be better off reading George Saunders than John Updike, or Zadie Smith instead of Margaret Fuller. I’m just throwing names out there, but the point is, find something you love and read as much of it as possible.

SS: What are some of your own aspirations as a writer?

JMO: I think my biggest aspirations as a writer start simple: #1, to finish projects! People with ADD tend to start a million projects and finish a few, if any, of them. So for now, my priority is to finish both Human Services and Of Gods and Men. Beyond that, I just want to write books that at least a few people really like. It’s an incredibly humbling thing when someone tells you that your work really resonated with them. It makes you want to write a special book just for that person because they took the time to read your work that they could’ve spent doing any number of other things. Time is a hot commodity in 2013, and people never seem to have enough of it. My biggest aspiration is that I’d really love to write for a living. I don’t even mean becoming rich and famous because of my work — though I’d certainly not turn it away. I just mean I’d give almost anything to spend each of my days with my imagination and churning out ideas on the page, and through that work (because make no mistake, writing is work!), be able to support/contribute to supporting my family. I think that’s a pretty kickass definition of “happiness!”

Dreaming to (Be)come Alive

In the way of the shaman, led by her own totemic animal guides (her animal selves), Hélène Cardona takes us on a journey through her inner-world, into the labyrinth of the poet’s unconsciousness where anything and everything is possible.

For Australian Aborigines, the beginning of the world is the ‘Dreaming’ (or the ‘Dreamtime’). Here the ancestors became manifestations of all living creatures and the elements. The Dreaming is the sacred seat of the Earth and infuses and inspires all aspects of tribal life; it is this network of complex relationships with the natural world reflected in the creation myths and songs that makes, evolves and informs everything.

In the way of the shaman, led by her own totemic animal guides (her animal selves), Hélène Cardona takes us on a journey through her inner-world, into the labyrinth of the poet’s unconsciousness where anything and everything is possible.

The dream opens forgotten worlds of creation.

(“Pathway to Gifts”)

In dreaming is the Divine created.

(“From the Heart with Grace”)

This, of course, is Jungian territory; yet, Dreaming My Animal Selves, does not offer conjecture on the meaning of dreams, there is little interpretation here; this is a poet’s personal metaphysical journey of discovery, where, by tapping into her ‘collective unconsciousness’, she reveals her ‘truer’ inner-self and begins to unravel the alchemical symbols of her very existence.

In the words of Jungian scholar, Marie-Louise von Franz, “If a man devotes himself to the instructions of his own unconscious, it can bestow this gift, so that suddenly life, which has been stale and dull, turns into a rich unending inner adventure, full of creative possibilities.” These, it seems, are the forgotten worlds of creation that Cardona is re-discovering, re-awakening.

And, through the Dreaming, the reader is informed that these forgotten realms may well be what the real time is (is there time on the outside?). As the poet tells us, you can’t capture a dream, you can simply move into its stream. The dream world is not only more real. It is entirely effortless.

…it’s so easy on the other side.

(“Illumination”)

The mind flows through like wind.

(“Breeze Rider”)

The more the poet explores her childhood at the foot of the Alps, on Lake Geneva, the more her fragments of memory intertwine and interweave to reveal a poetically invigorated mythology, a mythology built upon the bricks of both ancient archetypes and her own modern visions. Like the shaman, with the help of her animal selves, Cardona is conjuring herself (back) into life.

Through the glow I witness / the melodious dance of the wistful / wizard, statuesque sleek crane.

(“Isle of the Immortals”)

Eagle teaches / me to hunt … raptor / uncovering secret codes …

(“Parallel Keys”)

The dream is the wellspring of her creative healing process, the creature voices (now eagle, now coyote, now Peruvian horse), her guides—transmuting familiars who may be herself, or may, indeed, also be her ancestors.

In dreams like rain

my mother visits.

A bird in the shower

takes messages …

(“In Dreams Like Rain”)

And, who help her find her way without a map:

I’ll […] rely

on memory embedded in my mother’s embrace

on stormy nights at the foot of the Alps.

(“Dancing the Dream”)

Oh, but there is a map. The map of Cardona’s inner world is the book itself.

For the Indigenous Australians, ‘songlines’ are tracks across the land that mark the routes created by their totems during the Dreaming. Bruce Chatwin explores this in his interviews with tribal elders in his book The Songlines: “Aboriginal Creation myths tell of legendary totemic beings who wandered over the continent in the Dreamtime, singing out the name of everything that crossed their path — birds, animals, plants, rocks, waterholes—and so singing the world into existence.”

Cardona’s imagistic dream poems are timeless artifacts, little ‘songs of innocence’ from a primordial / universal age. Cardona’s Dreaming My Animal Selves is not only a poet’s spiritual awakening, but a sacred journey whereby each individual poem (or song) serves as a marker within the larger map of her inner geography, a map which, in turn, guides her through and breathes her back into her physical world with a renewed vigor—

On the cliffs where the wild ones come

to show themselves.

(“Pathway to Gifts”)

Reborn again, Cardona,

. . . seeps into sand in search of treasures.

(“Shaman in Residence”)

This is the poet as enchanter. We can’t resist the urge to follow her inside.

Her voice will not be silenced

for it is formidable

and echoes those of all beloved.

(“Dreamer”)

He Is In Every Sense An Awful Man But He's Also Sympathetic

What’s immediately impressive about Big Ray is that it works exactly the way that memory works, at least some of the time. Daniel Todd Carrier’s father has, by the time the novel begins, died for some reason.

Michael Kimball’s Big Ray is the kind of book that will occupy your complete attention for at least fifteen minutes after Molly Gaudry hands you a copy to look through in her living room. You’ll be drinking tea and eating tea cookies, but you’ll have to stop drinking the tea so that you can turn the pages. You’ll keep eating the tea cookies, which you’ll shovel into your mouth faster and faster as you follow Kimball’s narrator’s brief flashes of sequential memory farther down their self-amending rabbit hole. You’ll be so into it, that you’ll be a little peeved when Molly takes the book away.

What’s immediately impressive about Big Ray is that it works exactly the way that memory works, at least some of the time. Daniel Todd Carrier’s father has, by the time the novel begins, died for some reason. His death could be attributed to any number of reasons, but those are hardly important. This isn’t a murder mystery or a medical exposé. This is a human novel about how a human son remembers his human father, who has recently become very humanly dead.

Kimball’s narrative unfolds through some of the most authentic, most honest prose that I’ve come across. When I was reading Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle, someone told me that he wrote a chapter a day. It made sense; this method explained how he never got long-winded, how one chapter broke so naturally into the next. Despite the impossibly apocalyptic Ice-Nine and the off-the-wall Bokononisms it seemed honest, even confessional. Kimball’s bite-sized chapter sections, the longest of which are two and three paragraphs, do a great deal to make Big Ray feel at least as immediate, at least as “true.”

The titular Big Ray is a big, disgusting, abusive, dead man. His presence looms larger than his 500-pound frame in this book, and it’s easy to write him off as a caricature at first glance, but it’s hard not to sympathize with him. We see him as a boy, as a high school student that looks like James Dean, and as a Private First Class in the Marines, but never as someone who sets out to do the wrong thing. He is in every sense an awful man but he’s also sympathetic, and he’s a figure who you’ll find yourself wanting to know by the time you’re through the first few chapters.

Our POV character is a grieving son, who is equally intriguing. He leads us through memories of the immediate fallout of his father having been found dead in his apartment, and alternates this narrative with one constructed of childhood memories. All of these are presented from the perspective of an adult mind rationalizing these experiences little-by-little.

Toward the middle of the novel, Daniel Todd Carrier has been relating his history of abuse at the impossibly fast hand of his father Big Ray, when he offers this tiny, reflective interruption: “Sometimes, I still get the urge to fight my father. If my father weren’t dead, I would kick his ass.” This kind of evaluation is tempered with flashes of memory that express another kind of sentiment entirely: “Sometimes, in the mornings before school, my father would look at the way I was dressed and say, ‘Looking sharp.’ That always made me feel really good.”

Big Ray is a novel full of terrifyingly dry wit, disgusting medical problems, beautiful sympathy, and honest-to-god people. It’s a page-turner in the best sense of the phrase, and you’ll have a damn good time reading it.

You Just Need to Talk to Somebody: A Review of Scott McClanahan's Hill William

Some people might be a little startled to pick up a book and find a first sentence that reads: “I used to hit myself in the face.” However, Hill William wasn’t my first experience with Scott McClanahan.

Some people might be a little startled to pick up a book and find a first sentence that reads: “I used to hit myself in the face.” However, Hill William wasn’t my first experience with Scott McClanahan. Familiar with at least the gritty and quietly intense Crapalachiaand Stories V! out of the McClanahan canon, I was somewhat prepared. Of course, that’s still a hell of a hook line. No one can ignore that.

In brief, Hill William presents a main character who is pretty messed up:

I couldn’t get rid of the sick feeling in my stomach. I couldn’t get rid of the tightness in my shoulders like my head was going to pop off. And then it started playing in my head — the bad memories, the old bad memories. I made a fist. I took my fist and punched myself right in front of her. She shrieked and followed me into the bathroom.

She cried and said, “You need help baby. You just need to talk to somebody. You’re kind of fucked up.”

She said kind of to soften the blow. But I kept doing it—pop, pop. I fell to the floor. She screamed. I did it with the left hand. She screamed. I did it with the right hand. She screamed. Stop it. Stop it.

After McClanahan has his screwed up character solidly in our hands, the reader completely on board, the book descends into the character’s past. We proceed headlong into “the old bad memories.” What kind of experiences makes a person unable to help from mutilating themselves? What exactly happened that plays back like that in his head? Don’t worry, McClanahan quickly provides.

I just wanted to be cool. Derrick was a lot older than I was (like fifteen), and I thought he was the coolest. I was nine. He was always shooting guns, or sighting in his bow, or chewing tobacco, or talking about how he was going to kick some guy’s ass. I was six years younger and I always followed him around. One day he asked me to come and play Atari Pitfall with him. It wasn’t fifteen minutes into being there that he disappeared into his mom and dad’s bedroom. It seemed like he was gone for a long time, but I just kept playing and didn’t really think anything about it until I got killed or something.

I heard Derrick saying, “Hey. Come back here. I want to show you something.”

The prose is quiet. McClanahan just lays it out there. For a character who spends a great deal of time in worry and fear, there isn’t anything in the words to discernibly manipulate what the reader is going to feel from a given scene. There is a kind of bare poetry to the way the words are arranged, but it just is what it is. The writing comes across with such a this is what happened kind of tone that you almost start to feel before you quite realize what you just read. Frankly, it is so straightforward that you don’t see it coming. Then it hits you.

There is some real power in this book. It moves, and it moves mountains. It’s all the more impressive because McClanahan makes the movement seem effortless. If you can see the man behind the curtain as you read then you have better eyesight than I do. I just sat back and appreciated.

Though the subject matter certainly isn’t pleasant, my reading experience actually was. I enjoyed Hill William. McClanahan vividly brings “the old bad memories” forth, but the reader won’t be traumatized by them and start hitting themselves in the face. To the contrary, I think Hill William is a book people will be glad to read. I sure was.