How Much We Compromise: An Interview with Vanessa Blakeslee

This novel is heavily rooted in history and the Catholic Church, and is remarkably researched. Can you tell me about the research that went into this novel? How much of the story was formed before research, and how did the story evolve through the process of research?

RACHEL KOLMAN: Before Juventud, you’ve been known primarily as a short story writer. How was the process of writing and putting together this book different than your collection, Train Shots?

VANESSA BLAKESLEE: I don’t find one form particularly more challenging than the other—just different challenges, and I enjoy both. I found constructing the novel with the compactness of a short story to forever be a challenge—I’m an over-writer, certainly in the long form, and so I have to cut and cut and cut. Even when I think a scene or passage is tight, chances are I have to cut. Hopefully I’ve learned something about this when I sit down to draft the next novel, about focus and concision. On the other hand maybe that’s just my process, and those tangents shed light on other characters or as-yet-unforeseen places where the story needs to go. Occasionally you can repurpose what you cut, although not most of the time.

I see the main challenge between the two forms residing within the impulse at inception—asking myself what container the conflict is calling for, and what kind of meaningful satisfaction am I chasing? For the satisfaction of writing a short story is entirely different than that of a novel. I love both, I can see myself working in both for the rest of my life because I’m a dedicated reader of both forms. And yet there is nothing quite as gratifying as an epic story well told. As humans we are awed by sublime creation on a grand scale; it’s embedded within us. Or so Longinus pointed out centuries ago. I tend to agree, although that just may be my mood of late—a longing to lose myself in a bigger world, an epic story.

RK: This novel is heavily rooted in history and the Catholic Church, and is remarkably researched. Can you tell me about the research that went into this novel? How much of the story was formed before research, and how did the story evolve through the process of research?

VB: When the premise for Juventud took root in my imagination and I knew the story largely took place in Colombia, I had two main concerns: 1) how to set high dramatic stakes (life or death) and 2) how to keep my own interest in the material for the months or years it takes to write a novel. Many Americans have a cursory, if erroneous, understanding of the conflict in Colombia, gleaned from sound bites they’ve picked up about the drug war, cartels, perhaps the FARC, but little else. The more I researched the history of the guerilla movement and the formation of the cartels and the key incidents on the timeline, both on the Internet and in fairly dense scholarly works, the more riveted I became in telling a story that more truly captures the sociopolitical landscape of Colombia—one that shines a light on the atrocities of the paramilitaries as much as the guerillas, and includes the millions of displaced alongside the wealthy. The depictions we’re so used to seeing from the movies play up the “sexy danger” of Latin America: armored cars, bodyguards, lavish estates, gorgeous women. Those exist in Juventud, too, but in a way that I hope is much more balanced, lyrical, and revelatory.

Not surprisingly, the more facts I unearthed in my research fed the shaping of the characters: their wants, actions, and the eventual themes. I studied everything from YouTube videos of Colombian peace rallies from the time, to AP releases on hostage crises, to interviews with paramilitary leaders. I also reached out to Latin American Studies experts for the most recent, reliable, and often dense, texts on the subject. The brutality of the guerilla and paramilitary atrocities’ in the lives of peasants is unbelievably horrifying, and propelled me onward—the book became much more than a love story I wanted to tell, but about the voices of so many in Latin America who scrape by day-to-day in terror, and are silenced. I wrote a lot that didn’t end up making it into the final manuscript, but I hope that those who are moved by the novel will seek to uncover more about that part of the world on their own.

Characters are literally born from whatever fictional earth your story takes place. And in that sense, I felt it was inevitable that Diego have been a cradle-Catholic who came into manhood at the height of the cartels, lost his faith, and when ego brought him down, struggled to reclaim it. And when I came across the event in spring, 1999, of the ELN kidnapping the congregation of La Maria Church in the wealthy Ciudad Jardin district of Cali, I knew this had to affect my characters in some way, and La Maria Juventud was born. I had been wondering what kind of occupation—or preoccupation—to give the young man who was to become Mercedes’ lover, that her father wouldn’t like but would make him sympathetic to the reader, and this was it—that Manuel and his brothers would head up a youth movement for peace, and Manuel would reveal himself to be a natural leader. Through this lens, I found I could also explore other facets of Catholicism in a natural way—that the sexual awakenings between teenagers would clash with the Church’s doctrines on birth control, marriage, and the like. Mercedes is an atheist at the book’s beginning which allows her to observe her Catholic friends (and father) neutrally, although I see her as more of an agnostic by the end.

From early on in my research and drafting, I understood that to not include the Church would be impossible, if I was to be true to the story and the setting. Colombia is an overwhelmingly Catholic country; the very philosophy behind the guerilla movements in South America is that of Marxist liberation theology, which interprets the Christian faith from the perspective of the poor, and in the early days of the guerilla movements, the 1950s and 60s, adopted Marxist teachings in their advocacy for social justice. I was also in the midst of shifting away from the fervent Catholicism I’d been practicing in my mid-twenties because I couldn’t reconcile my personal stance on women’s and gay rights with the Church’s doctrine, but found myself reluctant when it came to Catholicism’s stance on social justice—a cornerstone that I believe Christianity, but especially Catholicism, very much gets right. I’m a huge proponent of “faith in action,” in that respect—the only way spiritual principles make sense to me is if they are lived out in practice. Otherwise, what’s the point?

The Catholicism also prompted me to bring in the Jewish thread to the book—I’m always looking how to complicate threads further to create more contrast and meaning. Wouldn’t it be interesting, I thought, if her mother is not only American but Jewish, and if her mother is on an identity-quest of her own, and if Mercedes eventually goes to visit her in Israel? And then we have the contrast between another decades-long conflict, that of Israel and Palestine, and the Colombian civil war. So in the latter half the book expands outward to reflect not just the issues of social justice and violence in South America, but the global conflicts still raging today. The common ground between Judaism and Christianity is unearthed, but also the divide between the religious and secular. Not to mention the resonance of what Mercedes has escaped from, after she learns the history of her maternal Jewish family prior to World War II.

RK: Tell me more about Mercedes, our narrator. Spending so much time in her voice, I imagine you grew very close to her. How did you develop her character? How was it to write her as fifteen, young and in love in Colombia, and then again as an adult?

VB: From the beginning the voice posed many challenges, not in the least that I didn’t know the ending to the story—the adult section—for quite a while. When the why? behind the story eludes you, the answer lies in probing the dramatic question more fully. Because the dramatic question focuses on how the events of her youth, and most crucially, how she sees them, impact her life long-term, the story belongs to Mercedes. Once I got there, I felt more certain that the book speaks solidly to a mature audience, not excluding the sophisticated younger reader. I suppose I could have structured the narrative differently—say, three third-person narratives, one following Mercedes, the others following Manuel and Diego—but I was more interested in Mercedes as an embodiment of the global citizen of today, the highly-educated Millennial who inhabits several different identities and cultures, and how she navigates the paths available to her. Education and access to birth control are enabling women around the world to make strides and command their destinies for the first time in human history; I found myself more invested in giving a female protagonist full rein, seeing how her roots in a conflicted country leave their imprint on her emotionally as she otherwise achieves success. I wasn’t so much interested in following Diego or Manuel as closely; their inner struggles wouldn’t have touched so much on the identity issues I was intrigued by in Mercedes. Structurally, I felt it should be fully Mercedes’ story in that it is presented as a memoir she’s writing—there’s a self-consciousness about the narrative, then, which hopefully allows the book to transcend the themes of love and career and illuminate her relationship with herself.

By following her out of Colombia and into adulthood, we also get the parallels and contrasts between the developing world of South America and the U.S., the violence Mercedes grew up with in 1990s Cali and that of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict when she takes her birthright trip to Israel. Much can be learned, I think, from studying how some countries long ravaged by war, corruption, and atrocities eventually do arrive at a lasting peace—even though this hardly means that the inequalities, prejudices, and the like have been solved. Far from it, but if this novel illuminates how no one escapes unscathed, by no means the elite, then I’ve done my job.

RK: There’s a great theme in this novel about the power of the truth and the idea of using lies to protect the ones we love. Was this a concept you meant to explore, or did it sort of fall into place? To you, how important is the idea of finding “the truth?”

VB: I love mind-bending novels where you find out, at the end, the way things happened turns out to be very different from what it seemed: The Blind Assassin, Atonement, Never Let Me Go, The Secret in Their Eyes, to name a few. In such stories perspective is key. So I wanted to explore those limitations, but didn’t exactly know how, nor if I could pull it off. I do believe that sometimes, it’s necessary to have reservations about what we divulge to those we care about. As a fiction writer, I’m always fascinated by the grey zone of moral ambiguity and how we navigate that as humans.

There are different types of truth: the kind we perceive, which is shaped by our own perceptions and flawed by our limitations, the truth that resides in facts and evidence, and the emotional truth. The diligent research required of the project only emboldened my interest and commitment to the book, for the more facts I uncovered, the more harrowing and urgent and true I found the themes. Juventud translates to “youth” in Spanish, and speaks to not only the singular world of the novel at a certain place and time, but the ongoing humanitarian crises in South and Central America—tens of thousands of children illegally crossing the US border, the continuation of horrific cartel violence in Mexico and other nations. Eventually Mercedes flees Colombia for the U.S. and her mother’s family, fully embraces her American identity, works first for the State Department and then becomes a journalist. I can’t think of another major work of literary fiction that so vividly illustrates the outcome of neoliberal economic policies in South America, their impact on the guerilla and paramilitary violence of late 1990s Colombia entangled with drug cartel operations, and how through these characters, the crises facing Latin America today are precisely and poignantly illuminated. In Juventud, landowners and upper class such as Mercedes’s father, Diego, Uncle Charlie, Ana’s parents and others wield a firm grasp on their wealth by secretly funding paramilitary armies who violently “cleanse” the countryside of uncooperative peasants or those they believe sympathetic to the guerillas’ (FARC and ELN) cause. Through the artifice of fiction, the novel stirs up disturbing and necessary questions about the decades-long crisis in Colombia, and the very “grey” role played by the United States in the implementation of solutions.

My hope is that readers of Juventud will gain a sharper understanding of what it means to live in Colombia and to greater extent, Central and South America, where the disparity between the “haves” and the “have-nots” is much greater than in the US—although the gap is widening here, quickly— and how violence and bloodshed arise from such disparity to negatively affect everyone, rich, poor, and in-between. This is also a story of how our perceptions very much shape our desires and decisions, not always to our own best interest. Inevitably we are molded and driven by what happens to us in our youth and how we perceive those events, a perspective which is limited and therefore flawed, yet unbeknownst to us at the time, and often for many years afterward. Through Mercedes, the novel reveals how we grapple to make sense of these formative individual experiences – and how as adults, we have the opportunity and means to gain clarity, responsibility, and forgiveness, and ultimately understand and transcend our past even if it will always remain part of us.

RK: The novel also explores some great feminist issues: there are times that even the 15-year-old Mercedes can see how she is being controlled and stifled. How does feminism inform your writing? Do you feel it’s important as a woman writer to contribute to the feminist conversation?

VB: First, I’m so glad to hear Mercedes’ cognizance of how she’s being manipulated at times by the men around her came through; getting her burgeoning awareness to hit the right notes took numerous drafts. I am a feminist, and I am a writer. Your questions remind me of the quote by Flannery O’Connor, from her wonderful collected writings, Mystery and Manners: “Your beliefs will be the light by which you see, but they will not be what you see and they will not be a substitute for seeing.” Because I believe in a woman’s right to have control over her own body, no matter what, in access to safe and affordable birth control, that as soon as any state power gains the ability to control a body, it has then seized control of the individual, male or female—these beliefs naturally trickle up through my imagination and into my fiction. Was I to consciously impose them upon the work, the whole experiment would turn brittle and fall apart, because the rules of art won’t allow for it.

Prostitution remains much more peripheral in the novel than the contraceptive subplot, but no less important. The openness and prevalence of prostitution in Latin America is perhaps what shocked me most during my travels. Colombia has laws similar to Costa Rica regarding prostitution, meaning that it’s legalized and regulated to certain zones, bars, brothels, etc. This, along with mandatory STD testing, serves to protect women (and society at large) as well as eliminate pimping. I hesitate to say “empower” because I find the practice of selling sex hardly healthy or empowering; if you’ve ventured into any of these “whore bars,” the mood is unmistakably sad. Mercedes’s brief brushes with putasare crucial to contrasting the different social classes: paths available to women, and lack thereof. This, I hope, illustrates the privilege of Mercedes and her circle—there are only so many jobs with airlines, hotel chains, or zip-lining tourists through the jungle, and far more women who must fare for themselves and provide for children, with far more limited options. I hope these subtle, more tertiary notes shed greater light on Mercedes, her dreams and fears. At one point when her plans to flee to Medellín with Manuel are taking shape, she mentions her fears of ending up in a barrio among prostitutes and the displaced. How quickly may any of us fall, without a safety net? Again, in this context, her fixation on a flight attendant career path ought to make more sense. I hope astute readers will see some of the broader social justice issues that the storyline barely scratches.

I also wanted to explore the assertiveness in Mercedes’s character through her sexual coming-of-age—to show a young woman who is comfortable enough in her body and her relationship to be proactive about losing her virginity in a healthy way, and up front about experiencing and deserving her own pleasure. She and Manuel “wait” a respectable amount of time before having intercourse, so they get to know each other’s character; I saw them as trusted friends by that point, and hope readers will, too. There are too few instances, in books and on the screen, that tastefully depict young men pleasuring young women, which prompted the bedroom scene with Manuel and Mercedes on the night of her birthday party. I’m not aware of cunnilingus concluding a chapter elsewhere in literature. Please enlighten me if such a scene exists!

RK: The second half of the book shows Mercedes in her twenties, with many of her decisions informed by the way she views her past in Colombia. I love the idea of how our misconceptions distort our worldview. Can you talk more about that idea and how it played into the novel?

VB: As we grow older and gain experience, we witness our ideals smacking up against practicalities that compel us to bend, to compromise if we want to keep after our missions at all, versus throw in the towel. When we’re young we usually can’t see the other factors at play, or if we’re aware of them we can’t yet understand the gravity nor nuanced entanglements that come along with the territory, and so it’s easy to profess a cut-and-dry approach. I suspect this reflects the gulf in generational thinking and subsequent behavior across the globe, cultural differences aside. The younger generations organize protests and take grassroots action; the elders legislate and hold summits. The youth cry, “Do something now!”; the elders say, “Let’s step back and discuss first.” To act wisely requires making decisions from somewhere in the middle—from the head and heart, so to speak.

How much we compromise, now that is the stickler, isn’t it? For I believe young people’s ardent convictions are a crucial reminder to older generations of the human spirit not standing for what is unjust, absurd, against liberty and basic human decency, and to press forward to behave better. So the trick as we age is to learn how to bend and accept realities that we can’t change, those that are relatively benign, and still work feverishly with the end goal in mind, without growing jaded and bitter.

Moreover, the overarching lesson in Juventud is a warning about what happens when emotions are running high, and we jump to conclusions and react impulsively. Nothing can change the past, and Mercedes has got to reap what she—and La Maria Juventud–have sown. But I think it’s also important to see the events through the cultural milieu, and consider that in a nation rife with corruption and vigilantism, “innocent until proven guilty in a court of law” is not necessarily in the citizens’ mindset—and likely wouldn’t have been in Mercedes’, until she came to the U.S. True to her upbringing as the daughter of Diego Martinez, in ultimate crisis teenage Mercedes learns to “take matters into her own hands” and unfortunately pays the price. But I think it’s very possible for her to forgive herself and heal the rift within her family.

RK: Some of my favorite parts to read were the moments of gorgeous imagery: walking the streets of Colombia, lying in Manuel’s bed with the fan whirring above, the image of her father in his bandana. Do you have a favorite moment or scene in the novel, or something that is of particular significance to you?

VB: The scene where Mercedes is on her way to Ana’s engagement party, and her driver stops on the valley road for her to talk to Papi as the sugarcane burns ranks among my favorites for imagery and lyricism, but also emotion. Still, whenever I read that passage, the poignancy of the moment between father and daughter moves me almost to tears.

RK: What were you reading while writing this novel? What works inspired you?

VB: Caucasia by Danzy Senna helped me hone the voice in later drafts, as Senna’s is very much a novel about identity and estranged parents, and how the narrator perceives her reality as a child vs. how she later comes to view those events as a young adult. Cat’s Eye by Margaret Atwood, also about memory although structurally different and rendered in present tense; I often turn to Atwood for her astounding imagery, and smart, fresh, often funny turns-of-phrase. I suppose The Lover was an influence, for the lyrical way Duras depicts a fifteen-year-old’s discovery of forbidden sex in the tropics. The Kite Runner, for plot and story; even though it centers on a friendship and not a love affair, the novel still deals with the subject of the now-Americanized global citizen returning to a homeland long ravaged by war, confronting individuals from the past, and navigating family dynamics. And many more of course: Julia Alvarez, Ben Fountain, the Greek playwrights, all at some point influenced Juventud.

You Can Let Go: A Review of Ben Tanzer's Lost in Space

Given that I’m a person who has never really wanted to have children, you might wonder what got to me about Lost in Space (a book of essays by Ben Tanzer relating to his fatherhood).

Given that I’m a person who has never really wanted to have children, you might wonder what got to me about Lost in Space (a book of essays by Ben Tanzer relating to his fatherhood). Admittedly, Tanzer managed to hook me with similar themes (though fictional) in his novel You Can Make Him Like You. Still, I have no kids and no real interest in having any . . . but I was interested in checking out this book.

I tried to figure out why Lost in Space intrigued me. It’s not just as simple as me realizing that I’m at least the child of a father and wondering what it might have been like on the other side, though that’s certainly part of it. For one thing, it isn’t like I haven’t had to consider the possibility I could become a father. There’s always that. Actually, now that I really think about the topic, I could probably keep listing reasons as long as I keep pondering. Motherhood or fatherhood (potential or actual), what was it like for one’s parents, or whatever, there are any number of reasons why people with or without children might be interested in someone’s thoughts on being a parent. Bottom line: this is a huge part of human life and I want to see inside.

Getting to the book itself, Tanzer delivers marvelously in these essays. I think of books on fatherhood and I immediately worry about schmaltz, oversentimentality. I worry about Todd Burpo. Whether it’s fair or not to have that as an immediate concern when sitting down with fatherhood writings, it’s what I worry about. However, I didn’t find that to be a problem in Lost in Space. There is sentiment, but not excessive sentimentality (this selection from “Towers”):

From the start, your relationship with him prompted you to feel things you had not allowed yourself to feel before. Emotions you had hoped to bury or avoid. The idea of them embarrassed you. You were above all that, and not because you were better than anyone else, but because you were not willing to embrace any of it. It was all too messy and real.

But not with him, never with him, you can tell him you love him all day long.

You can also imagine shaking him, though. Some- thing you never think about when dealing with adults. You know you’re not supposed to feel this way, much less actually say it out loud, and it’s not that you can truly imagine doing it, it’s just that you can’t not imagine doing it either.

He stops moving around so much.

“You can let go,” he says.

Parenthood essays also leave me cold when an author tries to hard to seem like a perfect parent, or when an author sounds like a parental version of Gomer Pyle. We all know no one is perfect, and we also all know that no one is really prepared. The big problem for me with either of these extremes is that they feel like poses, a mask the author has decided to present instead of his or her actual emotions. However, Tanzer makes clear that he is only doing the best he can at the same time that he doesn’t overplay it. The approach doesn’t end up feeling like a pose to me. To the contrary, it feels honest and real (this selection from “The Unexamined Life”):

Children are different of course. The shadows come later, but even talking about having children makes the chance for adventure seem less likely, and Debbie and I have definitely not been on enough adventures together. And yes, I know, people go on adventures when they are parents, but will we? I don’t know, which makes me think even more about regret and shadows, which leaves me spinning.

It also makes me want to run away.

Not that I want to run away from the idea of parenthood or Debbie, but for at least one last time I want to think I can be someone who takes chances and can live in the moment.

Debbie is not interested in any of that.

“Go, go somewhere I have been,” Debbie says, supportive, though maybe hedging her bets a little, “but go, and then come back, cool?”

My main impression from Lost in Space is being next to a confiding friend on a barstool. Mind you, not just a ‘bro’ with whom conversation only goes so far: sports, women, and no more. Instead I mean one of those close friends who really need to talk and let it all out . . . to tell you things that have real, personal gravity (this selection from “I Need”):

I need sleep, long and deep and full of dreams about love, sex, pizza, Patrick Ewing, and Caddyshack. In these dreams I will be so happy, smart, funny, and full of esprit de corps that interns will float by my office in low-cut blouses begging to hear my innermost thoughts on Game of Thrones. I will not worry about bills or love handles, and I will not think about my children, not for even one moment, yo. If they happen to make an appearance they will say “excuse me,” “yes,” and “please,” eat over the table using actual utensils, and not constantly bang their heads or mysteriously find their hands around the necks of one another.

In the end, Tanzer hooked me just as much with Lost in Space as he did with You Can Make Him Like You. He manages to hit a lot of different topics in these essays: whether or not he does the right things for his boys, worry about what could happen to them, concern about who they will become, desire to share in their lives, the need to have life of his own, trepidation about having children, and the decision to go ahead with surgery finalizing what children he will have. There are a variety of different aspects of fatherhood in here, approached in a variety of different ways. I still don’t think I truly know what it is to be a father after reading, but I think I have shared some of what it’s been like for Ben Tanzer.

I found Lost in Space to be intimate, insightful, and vulnerable. It has a weighty subject, but the writing doesn’t rely on the subject’s weight to get by. Whether you have kids or not, I can’t imagine someone reading this book and not being affected. In short — it’s good, yo.

He Makes us Laugh and Grieve Simultaneously: A Review of Joseph Bates's Tomorrowland

Literature — like all forms of art — is most successful when it entertains us andenlightens us. Sure, there’s a certain merit to a superficial tale whose only purpose is to help us pass the time, just as there’s a justification for relentlessly aggressive music or the shamelessly voyeuristic fad of “torture porn” (a genre which speaks volumes about our sadistically desensitized culture, of course). But to be truly worthwhile, a story should mirror our own fears, hopes, secrets, experiences, and hypocrisies with ingenious subtly and plenty of imagination.

Literature — like all forms of art — is most successful when it entertains us andenlightens us. Sure, there’s a certain merit to a superficial tale whose only purpose is to help us pass the time, just as there’s a justification for relentlessly aggressive music or the shamelessly voyeuristic fad of “torture porn” (a genre which speaks volumes about our sadistically desensitized culture, of course). But to be truly worthwhile, a story should mirror our own fears, hopes, secrets, experiences, and hypocrisies with ingenious subtly and plenty of imagination.

That’s exactly with Joseph Bates does in his latest collection, Tomorrowland. In fact, he does it ten times.

A resident of Oxford, Ohio (where he teaches creative writing at Miami University), Bates established himself as a visceral voice in the lit community long before the emergence of Tomorrowland. His debut work, The Nighttime Novelist, was published in 2010, and his fiction has appeared in several places, including InDigest Magazine and The Rumpus. As for Tomorrowland, its opening pages are covered with positive feedback, which isn’t very surprising given the way these pieces almost always amount to a fine duality between humor and heartache; his characters often find themselves in ridiculous situations that serve to demonstrate commentary on the human condition. In this way, he makes us laugh and grieve simultaneously.

Take opener “Mirrorverse” for example. A bittersweet sci-fi saga, it’s one of two selections that feel like lost Doctor Who episodes. Told in the first person, it actually begins as a jab at product reviewing (which makes writing this a bit ironic, I suppose). The speaker’s editor tells him to review a new invention (“The Belton Multiverse Spectrometer”) over the weekend. Essentially, the device projects alternate realities on televisions. From there we’re told that the editor wants a positive review, as is shown by this exchange:

I don’t know if I mentioned it, but they’re paying us for a decent review. So there’s that.

So it’s an advertisement,” I say.

It’s a reviewvertisement,” he says.

Anyone who’s ever written reviews can definitely relate to this dilemma. Once the story gets moving, Bates explores the all-too-familiar idea of trying to recapture lost love, as the protagonist uses the machine to explore untapped possibilities in which he and his ex-wife (who’s since remarried) indulge in the full potential of their “innocent” movie nights. Like everything in Tomorrowland, it results in a funny twist with moving undertones.

Bates also messes with form in two stories: “Gas Head Tells All” and “Survey of My Exes.” The former is a serious of questions and answers between an interviewer and the protagonist, whose head is literally a ball of flame. It’s a very detailed exchange overall, with plenty of unique details and honest reactions that make Gas Head feel as real as any other character in the book.

As for the latter, well, it’s absolutely brilliant; in fact, it’s easily the best of the bunch. A man sends the same series of questions (including “Do you know I never meant to cause you pain?” and “Did you know that I’m finally better?”) to all of his exes, ranging from Samantha (4th grade) to Shelly P (grad school). We’re told that the man suffered from depression in his thirties, and thus we get the impression that he’s trying to make amends to these women. These conversations reveal a plethora of refined yet monumental sentiments, and their implications are devastating (because this could happen to any of us).

The theme of unfulfilled potential also looms heavy over a few stories, including “Boardwalk Elvis” and “Yankees Burn Atlanta,” in which two middle aged men face embarrassment and self-loathing in the wake of trying to achieve their unique ambitions. These men are sorrowful yet charming (especially Elvis), and as a guy in his mid-twenties, I can envision myself in a similar situation in a few decades (reflecting on my lost goals, not dressing up Elvis or Sid Bream, just to be clear).

Perhaps the most important commentary in Tomorrowland is related to the increasingly narrow barrier between politics and religion, extremism and tolerance, and between authority and manipulation. “How We Made a Difference” is a humorous account of a bizarre Halloween night in which neighborhood children supplement the “trick or treat?” cliché for the mindless conservative rhetoric of [we assume] their parents and the media. For example, the first kids say:

You can’t trust Bob Jamney. . . . He’s a tax and spend Liberal. Can I have a Snickers?

and

Did you know that Embryonic Stem Cell Research takes developing embryos from the still-growing wombs of unwed teen black mothers impregnated by Phil . . . by Phil Clinton?

At first, it just seems silly, but when one considers the real life basis for cases like this (such as the Westboro Baptist Church), the story becomes a thinly veiled (and wildly intriguing) cautionary tale.

Likewise, closing chapter “Bearing a Cross” tells of a town that elects an egotistical Christian zealot as its new mayor. Naturally, the man (Wayne Butts, ha-ha) starts out with modest legislation and only slightly spiritual speeches, but soon his need for absolute power drives him to turn the city into a prison for anyone who doesn’t obey the rules. Eventually, sinners literally bare a cross for their misdoings. As imaginative and ludicrous as it seems on the surface, Bates is also striking up a very relevant and biting conversation about the possible outcome for America if we continue down this path. In other words, Wayne Butts serves as a stand-in for any one of the countless Bible Thumpers plaguing our society.

In the end, Tomorrowland does just what its title suggests—it expresses several potential worlds (both internally and externally) for our future. These pieces are filled with creative surprises, empathetic characters, and simple yet rich emotional consequences, which exemplifies how well Bates balances his own humility and confidence. There’s a level of originality and boldness here that is rarely seen, and these tales will stay with you long after tomorrow ends.

The Way I Sleep Is Sporadically and Often Desperately

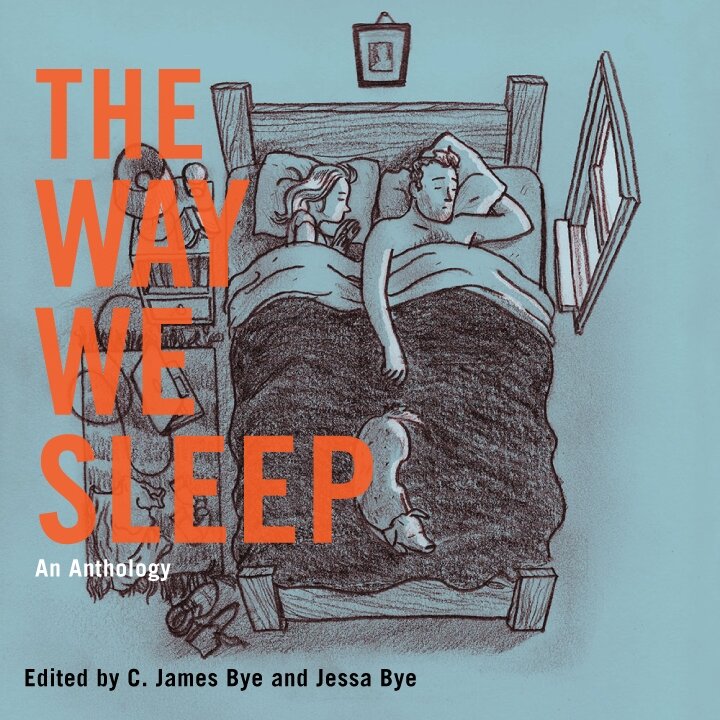

The Way We Sleep really covers everything, even the things that haven’t happened to me. It’s beautiful and grotesque and touching and tragic and funny and playful and philosophical and magical.

If you were to see my bed or even my bedroom, it might be hard to think someone sleeps there. Books, paper — so much paper just somehow everywhere — clothes, letters, those envelopes and boxes people mail books in, Gameboy Advance games — only Pokémon, really—a toothbrush, pens, used up batteries, and all kinds of random cords that belong or once belonged to something I needed. The way I sleep is sporadically and often desperately. Somehow, The Way We Sleep captures all of this and so much more.

I don’t like anthologies and have maybe read one or two before picking up Jessa Bye and C. James Bye’s The Way We Sleep. Knowing I had a deadline to read this, I was not looking forward to it. Dreading it, really. Anthologies or even just normal short story collection can take me months upon months to get through and so I was expecting to have to send some disappointing emails this week, explaining I was still only on page 20. But then just three sittings later, it was all over and I was shocked by how quickly it went, how easy it was, how beautiful and painful those pages were.

I have had a very tumultuous relationship with sleep and my bed. Dreams, though, we’ve always been on the same team. But the bed, it can be a lonely place, often a haunted place, a crippling and emotional place. Now, if I were to try to explain what my bed means to me, I’d probably just hand someone The Way We Sleep. It really covers everything, even the things that haven’t happened to me. It’s beautiful and grotesque and touching and tragic and funny and playful and philosophical and magical.

The writing in here is mostly top notch, with my favorites being by Roxane Gay, J.A. Tyler, Etgar Keret, Matthew Salesses, Tim Jones-Yelvington, Margaret Patton Chapman, and Angi Becker Stevens, whose story was my absolute favorite and the one I still cannot stop thinking about. There are a few stories that fall short, but this book is really full of amazing things, and for every story that misses, there are five that hit in ways you never imagined.

And it’s not just full of short stories, but also quick and funny and weirdly insightful interviews and comics. The comics were one of my favorite parts of the reading experience. Right in the middle of the book, it works as a sort of breather from the prose. Playful and funny and emotional, the comics really rejuvenate you and make it so you need to keep reading. For me, even more than that affect is the fact that I dream weirdly often in cartoon. I mean, to see my dreams reflected in a book is one thing, but to see them drawn out is really something else. Something deeply satisfying and beautiful.

The Way We Sleep just works. Maybe it shouldn’t, but it does. Jessa Bye and C James Bye have done a tremendous job here, because editing a book like this is much more than simply checking grammar. The structure and juxtapositions of this book make for an extremely gratifying reading experience and allows the pacing to never get bogged down by similarity of content or tone or style. This is a collection of stories, comics, and interviews that just speeds by.

Being released just in time for the holidays, I can’t recommend it enough as it would be perfect for friends, lovers, and family. There’s something in here for everyone, whether they’re looking for sex or love or humor or just something to pass these cold wintry nights.

So, yes, The Way We Sleep is something you want to read. But be sure to keep it next to your bed, just in case.