The Fun Part About Experimental Literature: On Ken Sparling's Dad Says He Saw You at the Mall

The premise of Dad Says He Saw You at the Mall is simple enough; the narrator, a Canadian library employee also named Ken Sparling, is concerned about his relationships with his wife Tutti and their son, Sammy. The stress of these relationships is clear, and his memories of his mother, father and stepmother (the fictional Sparling’s parents divorced when he was a child), help the reader understand that he didn’t have functional models for adulthood, so he has no idea what to do once he gets there himself.

I was first introduced to Ken Sparling’s work at — where else? — AWP, when I bought his book, Hush Up and Listen Stinky Poo Butt, and one of Ben Tanzer’s books as a package deal from Artistically Declined’s table. Admittedly, I was sold on Sparling’s book because of the title, and wasn’t prepared for the tightly episodic, slice-of-life prose therein. By the time I’d reached the halfway point of Hush Up and Listen, it occurred to me that Ken Sparling is one of the best kinds of writers, by which I mean the kind who shows readers that all the rules they learned from workshop are total bullshit.

So naturally, I jumped at the chance to review one of Sparling’s earlier novels, Dad Says He Saw You at the Mall, and it’s awesome, too. It doesn’t have the focus or grace of Hush Up and Listen, but it does have the same sense of fractured desperation and the same wayward, perhaps futile search for meaning. In much the same way that Philip K. Dick had to write We Can Build You before Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, this book is Ken Sparling’s realization that he’s onto something big.

The premise of Dad Says He Saw You at the Mall is simple enough; the narrator, a Canadian library employee also named Ken Sparling, is concerned about his relationships with his wife Tutti and their son, Sammy. The stress of these relationships is clear, and his memories of his mother, father and stepmother (the fictional Sparling’s parents divorced when he was a child), help the reader understand that he didn’t have functional models for adulthood, so he has no idea what to do once he gets there himself.

This all sounds like a fairly conventional middle-class domestic novel, but Sparling delivers it in vignettes that, through repetition and a non-linear structure that bounces between the present and the past, make for an uneasy atmosphere. The idea that he is dissatisfied with his wife and stays with her out of numb resignation isn’t stated, or even described, but the reader can sense it as their interactions become more terse and mundane as the book progresses.

The same can also be said of the narrator’s paternal frustrations; although he freely declares his love for his son (“I cannot believe Sammy will ever turn out to be less than perfect” and “I love him so much it is all I can think about sometimes” are two examples of this), the narrator’s fear that he is a mediocre dad wears on him as much as the messes, tantrums, and other exhausting realities of parenting.

Sometimes the narrator makes direct appeals to the reader, which range from taunts to challenges (“But you try telling the truth. Just try it sometime. Maybe you think you are already doing it.”) to questions that feel like cries for help (“will I have moments of clarity, moments just long enough to understand where I am and what is happening to me?”). These, along with a few sparsely sown moments of stunning description (“when she blinked, her eyelids fell like torn rags in the wind”) should be enough to keep readers invested.

The full effect of Sparling’s work — that is to say, the effect his structure has on tone and atmosphere — creeps up on you as you read, and that’s the kind of experimental approach that rewards the reader for his or her effort. I kept thinking about how something like this would get savaged in workshop, just torn apart for the arbitrary movements of the narrative lens, the mundane dialogue, the apparent refusal to ratchet any of this material into a conventional story with a rising action and so on. I kept hearing a well-meaning but persistent voice saying “show, don’t tell” as passages were crossed out or circled with a red pen.

That’s the fun part about experimental literature (which is really just plain old literature), though: there are few things more exhilarating than watching someone break rules and not only get away with it, but pull it off. Ken Sparling does that in spades.

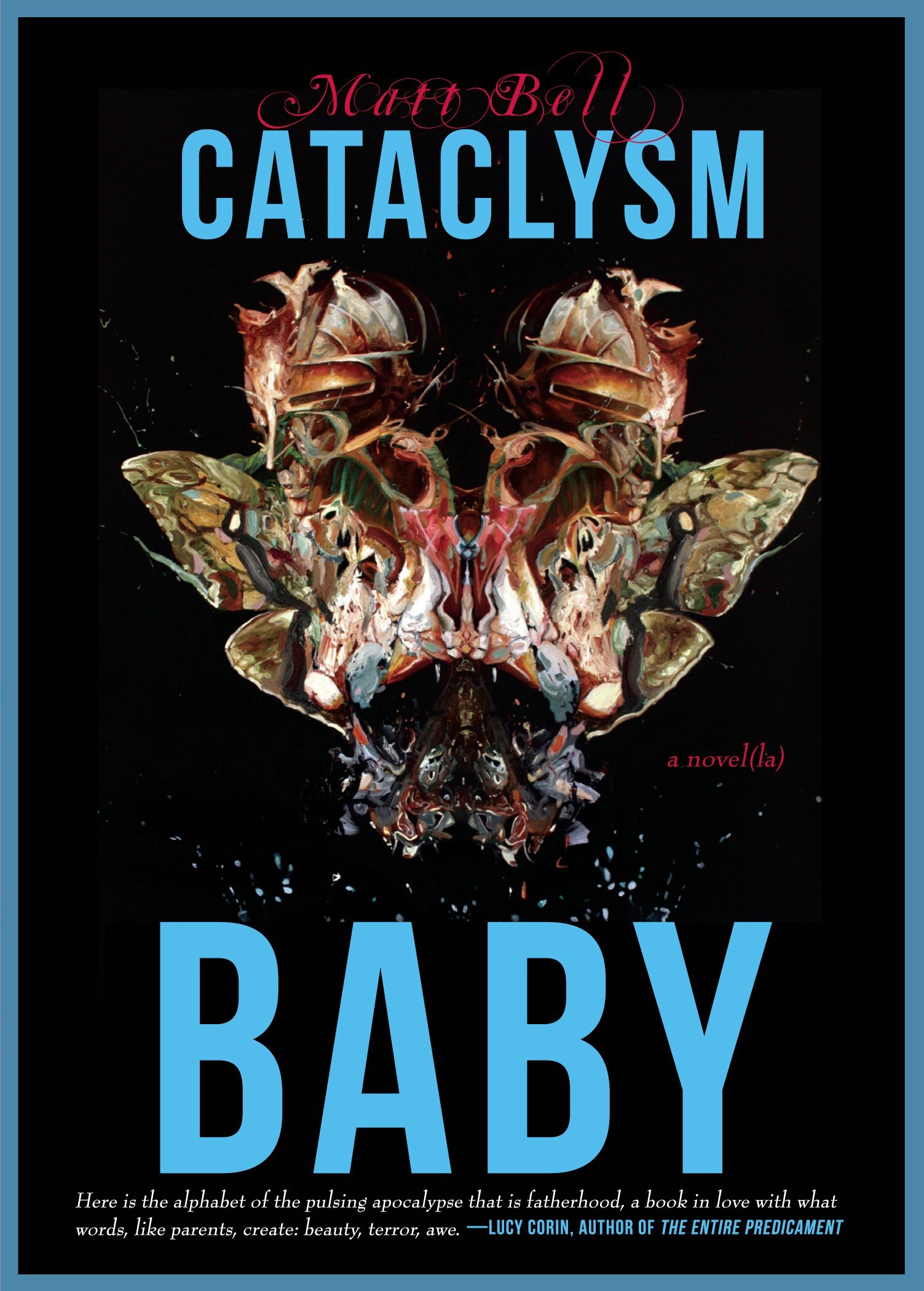

How to Save Your Friendships: A Review of Matt Bell's Cataclysm Baby

What keeps Cataclysm Baby from being just another menagerie of impossible disasters are the variations in the fathers themselves, who each struggle to deal with the guilt, anger, pride, and obligation fatherhood brings with it, apart from the apocalypse-fractured world outside the window. Some fathers regard their strange children with single-minded affection, others with scorn. Some sacrifice their mutated children, and some others sacrifice themselves. As the lights go out on the human race, some cling to hope that their children represent some sort of future, while others hold onto only what they can.

You know when someone develops a deep love for a movie, TV show, book, or video game and, before too long, it’s all they’ll talk about? Or how repugnant your sister is in the first few weeks of her new romance? We, as humans, are compelled to express our deep love for things, a habit which will murder your relationships unless you find people who love the same things you do (the reason people who like weird stuff like dubstep and electrocution tend to gather together).

This isn’t really a recommendation that you buy this book. Matt Bell’s name on the cover should be all the incentive you need to do that. But when you buy Matt Bell’s Cataclysm Baby, which you absolutely should, I’d recommend you buy at least a dozen copies, or one for each friend and family member you’d miss when they get tired of you obsessively talking about this book and stop returning your calls. Supplying all your loved ones with copies is an invitation into your new-found pleasure and will hopefully keep them from having sudden emergencies just as you arrive and staging interventions.

And talk about this book you will. You’ll talk about Bell’s prose, some of his finest yet, which has something of the biblical in it, something of the prophecy. About how you can imagine these stories told in dusty, burned-out rooms by grizzled fathers with thousand-yard stares sliding down the other side of survival. You’ll talk about this passage, and dozens more like it:

The day [my son] turns thirteen, he tells me I will wait three more months before I sneak into his room and read his diary, and that by then it will be too late.

He says, I know you could save us if you read it today, but I know you won’t.

You’ll talk about the references, the intelligent re-workings of Greek mythologies, Arthurian legends, and biblical stories. The Sirens make an appearance as three daughter mimics, luring villagers out into the floods destroying their world. A man, driven by the ghosts of his daughters, builds tower after tower, not to get closer to God, but to find the voice of his wife. A tanker carrying the world’s last women floats off the West coast, waiting for the world to be clean enough to deserve their return. A man chooses his own calf-child for sacrifice in a lottery. Bell’s handling of the sources is elegant, keeping to the core of what the stories are about, and might provide enough conversation material to ensure that your favorite barista will never ask how your day is going again.

You will probably, more than anything else, talk most about the endless variety Bell achieves, despite adhering to a restrictive formula. In almost every story, children are born deformed, mutated, something other, into a drying out or burning or drowning world. Of course, Bell shows off his impressive imaginative range with the “wrong-born” infants: some only balls of fur, some born as only invisible puffs of air.

What keeps Cataclysm Baby from being just another menagerie of impossible disasters are the variations in the fathers themselves, who each struggle to deal with the guilt, anger, pride, and obligation fatherhood brings with it, apart from the apocalypse-fractured world outside the window. Some fathers regard their strange children with single-minded affection, others with scorn. Some sacrifice their mutated children, and some others sacrifice themselves. As the lights go out on the human race, some cling to hope that their children represent some sort of future, while others hold onto only what they can. The family dramas, the reality of the fathers in these stories trying to hold onto a world that inexorably spins away, keep these stories from being just another meditation on the ways the world could end.

And the end. You will talk about the ending, the last chapter.

Obviously, this is the kind of book that can leave a reader sitting by himself on the bus, other passengers clutching purses and children while he mutters under his breath about how no one reads great books anymore. You don’t want to be that guy, so get a dozen copies. More if you actually like your family.

Robert Kloss On Reading

“I’ve never really thought about why I read or what it means to me. I’ve never had the need to justify the action, even when my father or my teachers made me feel like it was a less than healthy activity — I just sneaked around to do it. Honestly, I think I just fell into the habit when I was very young and I always kept at it…

"I've never really thought about why I read or what it means to me. I've never had the need to justify the action, even when my father or my teachers made me feel like it was a less than healthy activity -- I just sneaked around to do it. Honestly, I think I just fell into the habit when I was very young and I always kept at it. But, then again, I was always good at it and it was one of the few things I was good at so for whatever reason it was a natural activity. It was also one of the few things I liked to do so I did it whenever I could. At the moment I started to read I also started to write and I think the two have always been bound up in each other. Writing was the other thing I liked to do that I was also good at. Had I been able to draw or had I been able to sing or had I been more athletic things may have worked out differently. Slowly I think the writing cannibalized the reading, so now most or all of my reading happens so that I can write -- it's research or its inspiration, searching for power. I read how Melville wrote Moby-Dick while reading Shakespeare and Greek tragedy and Sterne and Rabelais and how those geniuses somehow unlocked his own genius. I have to admit I have always tried to do the same thing, with not quite as startling results. So I suppose if I have any requirement of the books I read, now, its that they should startle me. I don't read for a good yarn or to gain some insight into why people do what they do or some other abstract insight: I suppose I read to be startled and amazed by something brilliant and awesome, like an old time prophet caught in the glow and hum of the burning bush."

Michael Stewart Has Nothing to Apologize For

Michael Stewart’s The Hieroglyphics is a book we had to publish, & here’s why: We are our roots, and books that take those roots, both linguistic and visual, and churn them / crank them / rev them up into something modern and lyrical and rife, that is what drives Mud Luscious Press forward.

Michael Stewart’s The Hieroglyphics is a book we had to publish, & here’s why: We are our roots, and books that take those roots, both linguistic and visual, and churn them / crank them / rev them up into something modern and lyrical and rife, that is what drives Mud Luscious Press forward.

Michael Stewart came to us with The Hieroglyphics in its completed manuscript form, headed by the following description (read disclaimer):

"Horapollo Niliacus, who most likely never existed, wrote the original Hieroglyphica. It was a collection of some 189 interpretations of the Egyptian hieroglyphics, which were entirely, & unintentionally, fallacious. The collection was divided into two books, the first -- the one I am using in the excellent Boas translation -- dealt with seventy hieroglyphics & the second book with the remaining 119.

Using Horapollo’s original chapter titles & order, as well as incorporating many of his sentences with my own, I have attempted to engage in a kind of conversation. To this end, I have also incorporated lines from the Book of Jubilees, the Book of Enoch & the Old Testament among others.

I apologize to Boas, Horapollo, & the unknown writers of those other books for what I have done to their work."

I immediately dug in and was astounded by what he had carved out of and from these baseline texts. Michael Stewart has done in The Hieroglyphics not mere translation or redefining but the building of a new world from a previous one without losing or burying or wrecking the story.

Michael Stewart has nothing to apologize for: These hieroglyphics that he read and then rendered into words mount until they topple over and through us. Mud Luscious Press will forever be grateful to have had a small hand in the largeness of our collective history.

What is most fun to me about Svalina’s work is watching reviewers try to nail this book down to a genre or a category or a placement.

Mathias Svalina’s I Am A Very Productive Entrepreneur is a book we had to publish, & here’s why: Mud Luscious Press seeks to exist in the space between fiction and poetry, and there is perhaps no greater recent example of this than Svalina’s poetic fictions about failed businesses.

Mathias Svalina’s I Am A Very Productive Entrepreneur is a book we had to publish, & here’s why: Mud Luscious Press seeks to exist in the space between fiction and poetry, and there is perhaps no greater recent example of this than Svalina’s poetic fictions about failed businesses.

I knew from Svalina’s previous books Creation Myths and Destruction Myth that his vibe was our vibe, but when I read his Cupboard Pamphlet Series mini-book Play, I had to get in touch with him directly to see what else was in his writerly pipeline. And what was in there, sitting amongst his other brilliant words? I Am A Very Productive Entrepreneur.

The reviews have been very favorable and sales have topped 500 copies in just two months, but what is most fun to me about Svalina’s work is watching reviewers try to nail this book down to a genre or a category or a placement. They aren’t sure whether it is a novella or a collection or a series of linked poems or something else entirely, but that is exactly the feat of Mathias Svalina: He exists as we want to exist, between the between.

If Mud Luscious Press is building a niche inside of a niche, our feet our squarely planted in a writer like Mathias Svalina and a book like I Am A Very Productive Entrepreneur. He is one more very important building block in the work that Mud Luscious Press wants to be known for decades from now.

I am reading your book right now. It is goddamn beautiful.

Sure, the book is dark. Maybe a bit brutal. Disturbing in parts, you know, disturbing like that horrific scene from a movie you still remember and are frightened by even though you saw the movie ten years ago? The whole book is that feeling.

Via the Facebook, I told Robert Kloss, "I am reading your book right now. It is goddamn beautiful. And I might have squealed 'oh my god now he gets a cat companion' at one point."

Kloss replied, "I don't think I could put 'love' in the title w/out a cat companion."

For me this cat companion is what Kloss’s How the Days of Love & Diphtheria hinges upon. Sure, the book is dark. Maybe a bit brutal. Disturbing in parts, you know, disturbing like that horrific scene from a movie you still remember and are frightened by even though you saw the movie ten years ago? The whole book is that feeling. That feeling of vomiting out of fear and then being forced to sit with your vomit. Spend time with your vomit. Maybe get to know your vomit and learn to appreciate it. A thing that’ll follow you everywhere and be disgusting and between your teeth and make you feel like shit.

But, you don’t have to feel this bad. You don’t. Because -- there’s a cat companion. A beautiful white mewling kitten that’ll sleep at your feet and understand you and keep you safe. I read this book much more comfortably once the cat companion was introduced.

I’ll admit I worried about the cat. I thought, What if Kloss kills this cat? I read sentences slowly. Each page, very slowly. I thought that if I read it slowly enough, the cat would remain safe. If I crept up on the words very quietly there’d be no way for Kloss to surprise me, killing the cat. I thought, if Kloss kills the cat, I am not going to be his friend on facebook. And I needed desperately for Kloss to keep this cat safe. I wish could have spoken to him while he was writing this book and told him how important this cat’s safety was to me.

I worried maybe Kloss would sneak into my house, skin my cats and then they’d be shamed, running through the house as pink-furless cats. Kloss makes me nervous, but I don’t have to meet Kloss in real life. We can be friends on the Internet, where my cats feel safe.

And I can assume and hope (from photos on the Facebook) that Kloss is also a cat lover and this cat companion’s life was important to him. I liked to think keeping the cat safe among such danger and ruin was hard work.

How the Days of Love & Diphtheria is a beautiful object composed of thoughtfully and artfully written sentences. It amasses to much more than its parts and though it’s small, just fifty pages, the motherfucker weighs a ton.