An Interview with Roxane Gay

I’m interested in why we read what we read. Why we pick up the particular books that we do, and why we keep at them. What brought you to Battleborn? What led you to read it for the first time, and why did you want to talk with me about it here?

For this series I’m asking writers I love to recommend a book. If I haven’t read it, I read it. Then we talk about it.

In this installment, I’m talking with Roxane Gay about Battleborn by Claire Vaye Watkins.

Roxane Gay’s writing appears or is forthcoming in Best American Short Stories 2012, New Stories From the Midwest 2011 and 2012, Best Sex Writing 2012, NOON, Salon, Indiana Review, Ninth Letter, Brevity, and many others. She is the co-editor of [PANK]. She is also the author of Ayiti. You can find her online at http://www.roxanegay.com

* * *

Colin Winnette: I’m interested in why we read what we read. Why we pick up the particular books that we do, and why we keep at them. What brought you to Battleborn? What led you to read it for the first time, and why did you want to talk with me about it here?

Roxane Gay: This book was sent to me by a publicist at Riverhead. I hadn’t even heard of it, but once I started reading, I couldn’t put the book down. I was excited to discuss the book with you because it has been, by far, my favorite book of the year in a year of great reading.

CW: Most, if not all, of these stories focus on characters who are struggling with the past, and who will likely continue to struggle after the story’s end. In your opinion, what is the function of a book like this? To observe and report? To capture a state, or states, of being? Are there therapeutic efforts here? All/none of the above?

RG: I’m sure writing is therapeutic for many writers but I think there’s a lot more than that going on here. This is a book about how strength is forged and how sometimes, we cannot help but succumb to our weaknesses. The collection’s title really shapes how the stories are read and really helps each story capture this sense of what it means to be battleborn.

CW: Or, more specifically, what did the book offer you?

RG: As I read these stories, I wanted nothing more than to keep these stories near me, always. There is such control and grace in each story. Watkins tackles complex and intense subjects but there’s no melodrama here. Not only did I derive an immense amount of pleasure from reading Battleborn, I learned so much as a writer.

CW: What is a story like “The Diggings” doing in a collection like this? It was one of my favorites, but it’s certainly an outlier.

RG: I don’t really think “The Diggings” is an outlier. On the surface it seems like that because it’s set during the Goldrush and it’s a story about brothers but it’s also a story about desire and desperation and suffering and you can see those themes in most of the stories in this collection. I tend to think of this book as a masterclass. The range of stories is simply amazing and so when I consider Diggings within the context of the rest of the collection, I think, “Of course.” Not only does it fit thematically but it also fits with the diversity of the overall collection.

CW: I recently drove from Texas to California. We passed through Las Vegas on the way and eventually began to see the brothels in the small towns that surround it. It was a peculiar sight: rows of 18-wheelers and compacts alongside a few double-wides marked with a sign that read something like “Shady Ladies Ranch.” Watkins takes on one of these brothels in “The Past Perfect, The Past Continuous.” A lot of us have images of the places written about in the book — Vegas and the surrounding desert are iconic images — but few of us have experienced the intimacy of a life lived there, or even an extended visit. Watkins gives us insight into these intriguing places, or helps us imagine them a little more fully. How did you react to the function of place in this book? In many ways, the book is its setting, and those who populate that setting.

RG: Place is everything in this book, an inescapable gravity for the stories. I felt totally immersed in the stark beauty — both natural and manufactured — of the West and how that starkness shapes the people living within that landscape.

CW: Which story sticks out to you as best exemplifying what this book has to offer? If you could only recommend one story, rather than the collection, which would it be, and why?

RG: My favorite story is “Rondine Al Nido,” but my first instinct was to say that every story is the best in its own way. “Rondine Al Nido,” though is something else. The narrative frame intrigues me because it keeps you sort of off kilter. The story is disturbing but we see these rather unpleasant moments unfolding in really subtle increments. The horror, for lack of a better word, builds so slowly that it becomes almost bearable. The elegance of how this story was told takes my breath away.

The Way I Sleep Is Sporadically and Often Desperately

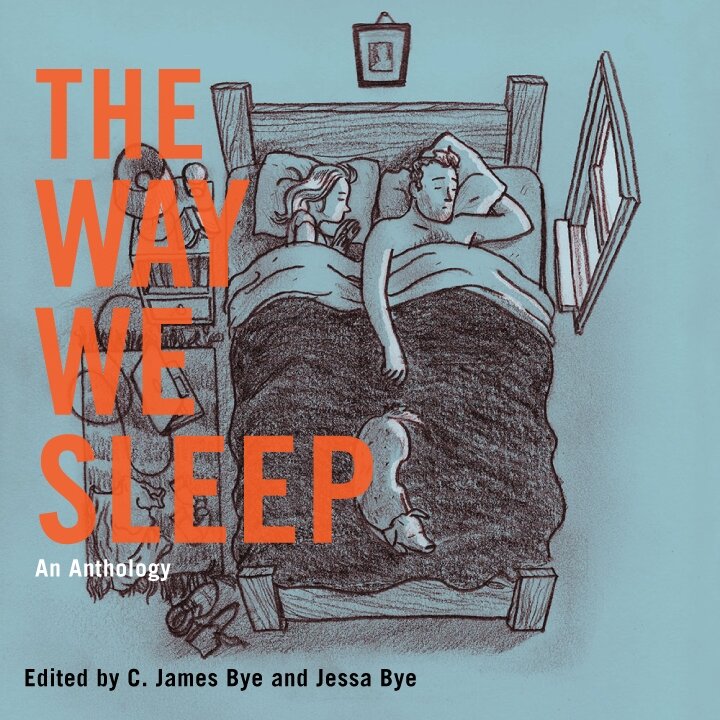

The Way We Sleep really covers everything, even the things that haven’t happened to me. It’s beautiful and grotesque and touching and tragic and funny and playful and philosophical and magical.

If you were to see my bed or even my bedroom, it might be hard to think someone sleeps there. Books, paper — so much paper just somehow everywhere — clothes, letters, those envelopes and boxes people mail books in, Gameboy Advance games — only Pokémon, really—a toothbrush, pens, used up batteries, and all kinds of random cords that belong or once belonged to something I needed. The way I sleep is sporadically and often desperately. Somehow, The Way We Sleep captures all of this and so much more.

I don’t like anthologies and have maybe read one or two before picking up Jessa Bye and C. James Bye’s The Way We Sleep. Knowing I had a deadline to read this, I was not looking forward to it. Dreading it, really. Anthologies or even just normal short story collection can take me months upon months to get through and so I was expecting to have to send some disappointing emails this week, explaining I was still only on page 20. But then just three sittings later, it was all over and I was shocked by how quickly it went, how easy it was, how beautiful and painful those pages were.

I have had a very tumultuous relationship with sleep and my bed. Dreams, though, we’ve always been on the same team. But the bed, it can be a lonely place, often a haunted place, a crippling and emotional place. Now, if I were to try to explain what my bed means to me, I’d probably just hand someone The Way We Sleep. It really covers everything, even the things that haven’t happened to me. It’s beautiful and grotesque and touching and tragic and funny and playful and philosophical and magical.

The writing in here is mostly top notch, with my favorites being by Roxane Gay, J.A. Tyler, Etgar Keret, Matthew Salesses, Tim Jones-Yelvington, Margaret Patton Chapman, and Angi Becker Stevens, whose story was my absolute favorite and the one I still cannot stop thinking about. There are a few stories that fall short, but this book is really full of amazing things, and for every story that misses, there are five that hit in ways you never imagined.

And it’s not just full of short stories, but also quick and funny and weirdly insightful interviews and comics. The comics were one of my favorite parts of the reading experience. Right in the middle of the book, it works as a sort of breather from the prose. Playful and funny and emotional, the comics really rejuvenate you and make it so you need to keep reading. For me, even more than that affect is the fact that I dream weirdly often in cartoon. I mean, to see my dreams reflected in a book is one thing, but to see them drawn out is really something else. Something deeply satisfying and beautiful.

The Way We Sleep just works. Maybe it shouldn’t, but it does. Jessa Bye and C James Bye have done a tremendous job here, because editing a book like this is much more than simply checking grammar. The structure and juxtapositions of this book make for an extremely gratifying reading experience and allows the pacing to never get bogged down by similarity of content or tone or style. This is a collection of stories, comics, and interviews that just speeds by.

Being released just in time for the holidays, I can’t recommend it enough as it would be perfect for friends, lovers, and family. There’s something in here for everyone, whether they’re looking for sex or love or humor or just something to pass these cold wintry nights.

So, yes, The Way We Sleep is something you want to read. But be sure to keep it next to your bed, just in case.

Glimpses of Personal Secrets, Situations of Real Human Beings: Roxane Gay's Ayiti

Gay’s first book, Ayiti, is infused with every one of her blog’s virtues: it’s funny, sad, bristling, kind, and contemplative. The collection comprises stories, poetry, and nonfiction, and the divides between the three are artfully blurred.

Ayiti is the first book I have ever read by an author whose work I discovered on a blog. Roxane Gay is a regular contributor to HTMLGIANT, “the internet literature magazine blog of the future,” which I unearthed (and obsessed over) in my senior year of high school, desperate to become a part of the “indie lit. scene.”

I enjoyed Gay’s posts so much that I began following her personal blog where Gay writes with wit and heart about writing, rejection, teaching, her life — oh, and films, brilliantly, uproariously. (I read her reviews of both Transformers 3 and Breaking Dawn at work and nearly choked trying to suppress my laughter.) To this day the only things online I check more frequently are my email, Facebook, and xkcd.

Gay’s first book, Ayiti, is infused with every one of her blog’s virtues: it’s funny, sad, bristling, kind, and contemplative. The collection comprises stories, poetry, and nonfiction, and the divides between the three are artfully blurred. Its subject is Haiti, its central topic the Haitian diaspora experience, but its themes — among them the strength/fragility of familial bonds and the real cost of human dignity — run far deeper.

It is refreshing, after reading and hearing ad nauseam the same maudlin but feel-good narrative about Haiti, to see its stories told tenderly, straightforwardly. Like most great literature (and unlike much shameful journalism), this collection profoundly respects the complexity and diversity of the situations of real human beings.

Gay’s prose is patient and, better, patiently-revelatory. Ayiti is smart but never erudite. Frequently, the pieces feel like glimpses of personal secrets. The reader plays the role of close confidante, a receiver of souls spilled forth.

The first piece, “Motherfuckers,” begins: “Gérard spends his days thinking about the many reasons he hates America that include but are not limited to the people, the weather, having to drive everywhere, and having to go to school every day. He is fourteen. He hates lots of things.” Gay knows how to express complex truths, evoke specific senses, without asking the reader to meet her halfway.

In November, 2009, in a blog post titled, “Wish I May, Wish I Might,” Gay worried about the fate of Ayiti, then unpublished. Was it too “ethnic” for publication? She wondered, “Are there any independent publishers who don’t mind such intensely thematic writing? When I see what’s being published, I really worry that there just isn’t a place for a collection like this to find a home.” This story ended happily — Gay’s beautiful little book found its home — but the questions behind her worry remain relevant, even essential.

Ayiti is unapologetic in its focus. It is brave enough to concern itself with a million facets of human life, to employ unique lens after lens, without wavering in its decision to be about Haiti and Haitians. This quality is rare in modern American literature. Ayiti, I hope, will be encouragement that collections of its kind are valuable, even necessary. But it is, of course, an outstanding debut before it is a political statement. And more than anything I hope it is a step toward earning Roxane Gay the readership her work has long deserved.