Fragile Threads, from Earth to Sky: A Conversation Between Cindy Rinne and Toti O’Brien

Cindy: The story looks at gay rights, women and those identifying as women having a voice. Although the story is set in the distant past, the issues are current.

Toti: Mine is not a story of flight, but it's a story of long distance, of the courage it takes to part from one's roots while still remaining, somewhere, connected.

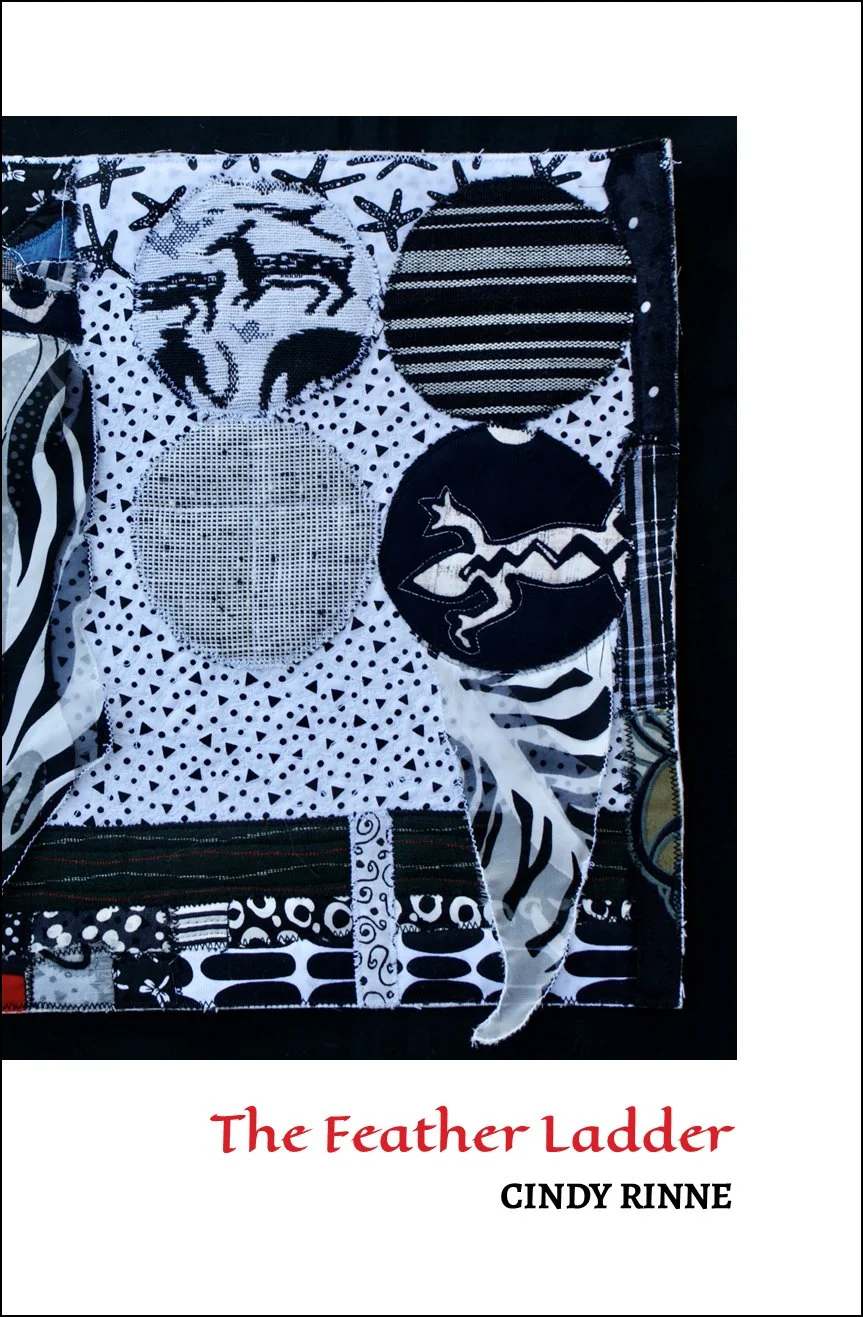

Cindy Rinne creates fiber art and writes in San Bernardino, CA. A Pushcart nominee. Her poems have appeared in literary journals, anthologies, art exhibits, and dance performances. Author of: The Feather Ladder (Picture Show Press), Words Become Ashes: An Offering (Bamboo Dart Press), Today in the Forest with Toti O’Brien (Moonrise Press), and others. Her poetry appeared in: The Journal of Radical Wonder, Mythos Magazine, Verse-Virtual, and others.

*

Toti O’Brien: Cindy, I remember when I first heard you read from The Feather Ladder. You were handling the very first copy! The book had just been released. It must have been the Fall of 2021—of course, we were grappling with the pandemic, trying to keep our creative souls and hope alive. I was sitting on the floor of the gallery where your reading took place in conjunction with an art opening. I recall being literally carried upwards by both your imagery and delivery, lifted in a world magical and mysterious that defied gravity. In a landscape of intermittent lockdowns and endless isolation, your aerial verse invoked the idea of escaping the labyrinth from above.

Can you briefly explain the core idea of this book?

Did you actually conceive it during the pandemic? If not, did the pandemic influence its development or its final shape?

Could you say something about where the original impulse came from?

Cindy Rinne: This novel in verse is a coming-of-age story for The Feather Keeper. He is sought out by a group of birds to help them fulfill their dream. He also discovers his mysterious origins because of this quest. Prophecies weave through the story for The Feather Keeper to be fulfilled as he chooses to take this journey.

Owl responded, Owl magic to protect your skin. It will be a night to your fingers.

The original story, which was longer, was conceived several years before the pandemic. The only effect the pandemic had was that the publisher delayed publication until things opened again.

The original impulse came from an idea about a group of birds speaking with The Feather Keeper about their idea to build a ladder reaching from earth to the sky. Then humans could get off the ground and out of their routines.

I made up this myth based in Neolithic times. In the story several times, their new idea receives opposition because there is fear of change. There is also support. As the journey continues, several characters who are not birds help them and The Feather Keeper. They meet with Sitka Spruce, Thunder Sun, Clear Sky, and Stone Woman.

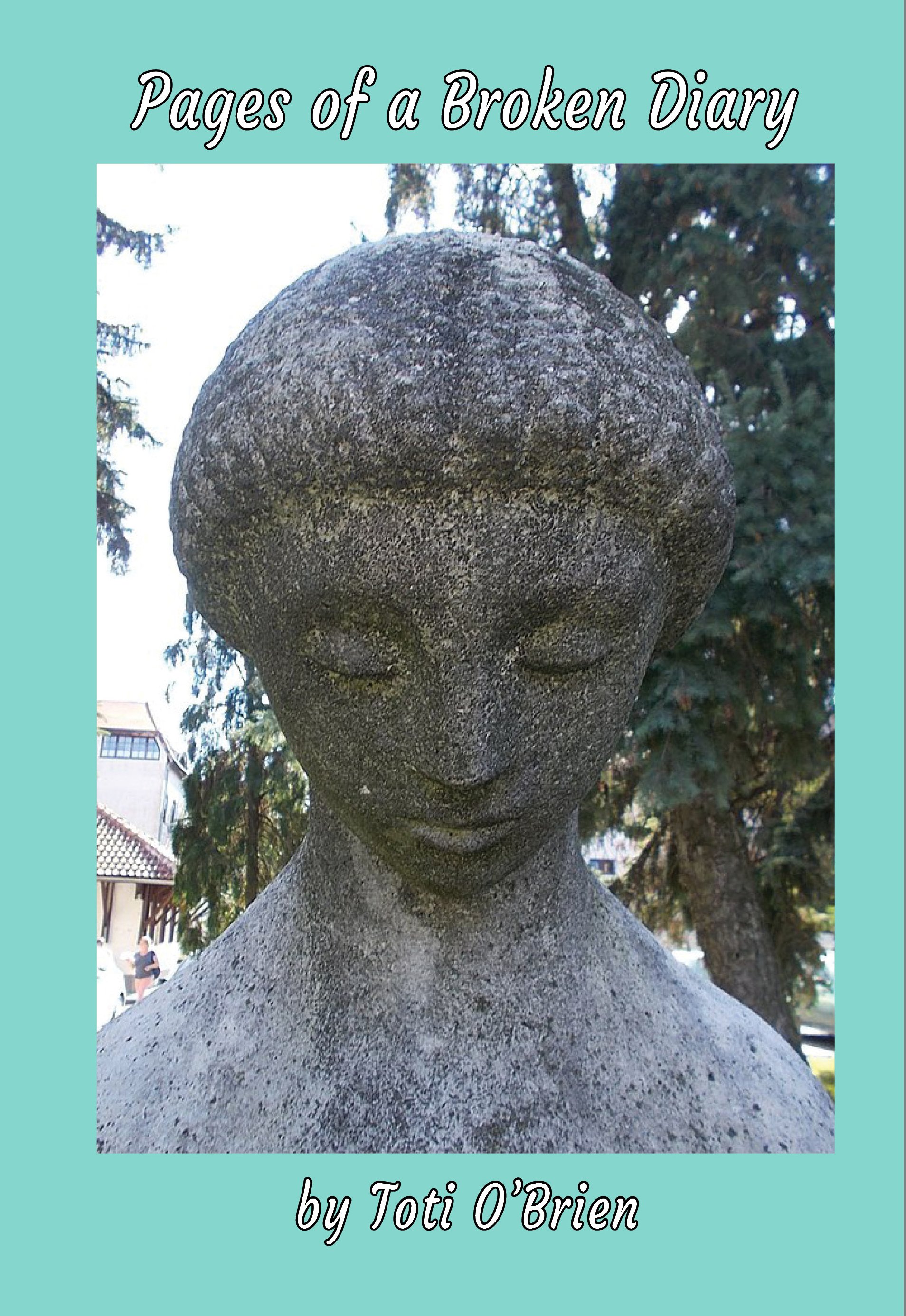

A year later with various versions of COVID, Pages of a Broken Diary is launched in the same gallery captivating the audience. Your delivery is passionate. Although I know you well, there is much to discover in this book. Can you talk about the form in this book? Do you see it as a memoir in fragments through prose or short stories? Why not poetry?

This book seems to go deeper and is your most vulnerable. “I am an orphan at soul.” The origins? Why now?

TO: Thank you, Cindy. “There is much to discover,” is probably the best comment a book could wish for! I see Pages of a Broken Diary as a collection juxtaposing different “formats” and “tones” rather than different “genres.” Some “pages” are clear, memoir-like narratives. Other pages are indirect, elusive. Some are very brief and read like prose poems. This contrast of voices and moods is deliberate. For me, it echoes the kaleidoscope of memory—the way life and its complexities speak to our mind/heart when we reflect on our past.

The book “reads as a memoir” because it strongly focuses on childhood and coming-of-age, family and relationships, motherland and displacement. Still, it doesn’t trace a life story, and the margins between fiction and nonfiction are never defined. My intent was to gather into a cohesive whole my reflections in the above-mentioned areas, delving into them with whatever means I could handle—thoughts, feelings, recollections, hypotheses, sheer imagination, irony, paradox, the lyrical, the documentary, you name it—and then offer to the reader not the result of my questioning, but the questioning itself.

I would think of a memoir as a detailed photograph, with recognizable scenery and portraits—sometimes, as one of those collages juxtaposing many small pictures—sometimes, maybe, as an album one could leaf through. Pages is none of this. Imagine it as a scatter of incomplete, blurred snapshots. Some of them might be distinct, and you seem to recognize this or that—but in the next one the same face is blurred—in the next one, the character or the landscape or the epoch have changed. Think of it as a bunch of puzzle elements sparse on a coffee table. The puzzle must be assembled, and each reader will do it in her unique fashion.

Origins, you say. I love how you simply speak the word, how you just pose it there. Are you asking me why I look back? What I am seeking? Let me ask you first, then… Why did you made up a myth based in Neolithic times?

CR: I decided to push the story back in time when community just began to be a concept and tribes with a chief were starting to form. The Neolithic culture includes farming and the use of metal tools. This was a time when the earth, goddesses, and the stars were honored. We need to bring this back. They wore animal skins. Cave paintings show hunting. I could include hyena and lynx.

The Feather Keeper talks with animals instead of hunting or farming. He’s still a nomad. This character didn’t begin as a Two-Spirit who embodies both the masculine and feminine. I discovered this term at an art exhibit of photographs after the myth had been written. It felt right. He probably would have been accepted back then, but LGBTQ Americans and beyond remain vulnerable to violence and hate. I write ancient / present and brought issues of today into the story.

The book is about social justice, courage, and magic. Myths last because of truths contained. I am a storyteller. Most of my poems contain a story. Sometimes I tell the story over several poems like this novel in verse does.

The style in Pages of a Broken Diary is conversational. Unpolished. Raw in places and lyrical in others. I feel I am with you in the push / pull of uncertainty, a timid present. How spontaneous is your writing? Do you think this allows the reader to bring their story easily? Is this important to you?

TO: As you say, the style in Pages is sometimes conversational, sometimes lyrical. I would not say unpolished because, as an ESL writer, polishing for me is a must—it needs to be agonizing, relentless. But, yes, my first drafts are spontaneous, unplanned, uncontrolled. To me, that is the only way to let “row” and “vulnerable” freely emerge. When they do (boldly show themselves in the nude) they speak to the reader in a different way. Closeness to the reader is important to me. I seek for a dialogue to be established, as authentic as possible, even if mediated through the written page. When I write in a conversational mode I am truly speaking with you, whoever you are. When I withdraw into the lyrical, elusive, non-linear, I am inviting you to behold a monologue happening in a “public sphere of privacy.” I am alone, but the spotlight is on, and you are welcome to witness the “push / pull of uncertainty.”

I firmly believe that the most vulnerable, the most open is the writing, the most it allows readers’ feelings and stories to resonate and emerge in response. And that is the whole point, is it?

You have mentioned “fear of change” as one of the motifs in your book. It is what creates obstacles that need to be overcome in order to build the ladder. But your novel is also permeated by the opposite force, a desire for change, which finally prevails. I wonder if “a desire for change” in the present is what prompts you/us to look back, as if wondering, “how did we get here?” As if, gazing at the past with clear eyes, we could see what we wish to keep and what we don’t want to repeat. Is there something in particular that your book sets to change, might be able to change?

CR: Opposition comes from those who say, Humans were not meant to fly. This can include the idea of are dreams possible? When my first book was published, I realized I was an author. A dream to have a book barely seemed possible. This dream included community from critique sessions to poetry readings. There are many allies in this story.

The ego rises up and says, You are not a good enough writer. Do people care about myth? On the other hand, others can be jealous or try to sabotage. The ladder builders face destruction but learn determination. For me it means a lot when a story or poem touches one person. You and I have discussed the power story holds.

It takes courage to follow your dream and to navigate the unknown. Pushing through the fear is a test for the birds and The Feather Keeper. He says, I will climb when no one else is willing. Recently, I decided to do performance poetry. I love making the writing real in a different way using props, costumes I make, and the movement of my body. In The Feather Ladder, he takes a stand. Opposition comes in the form of power struggles. The Feather Keeper acts in the balance of knowing when to negotiate, be humble, and when to be bold. He keeps the focus of the bird’s dream. In the process, he discovers what is important.

The story looks at gay rights, women and those identifying as women having a voice. Although the story is set in the distant past, the issues are current. I look at the situations of climate, ecological, political, and cultural chaos today. Even think about how this could be a banned book like the feather ladder falls apart. Then I wonder if I/we can find a gift to share with others like The Feather Keeper did? Can we work together to bring change and follow our dreams?

We weave worlds magical and mysterious and defy clear formats. Even in what appears to be very different books, there’s links. Discuss.

TO: Yes, there are definitely links between these two books! Otherwise, we probably would not be having this conversation. I can think of two main connections, right away. One is almost obvious. As per our visual art, we both build books out of fragments, juxtaposing bits and pieces instead of embracing a unified, fluent narrative. As per our visual art, we both use shards that are asymmetrical, different in texture and size. I have discussed my frequent and deliberate changes of tone, POV, format. The building blocks of your book are all poems, but they vary as well. The story is told by a polyphony of voices, the POV constantly shifts, even the font/format does. It seems that we both like sharp angles, such as the zigzag point you frequently use in your textiles, or my ripped shreds of papers.

Another, very strong similarity pertains to contents. Both of ours are coming-of-age story, though “age” is not insisted upon—a detail that rather likens them to tales of initiation, testimonials to a process of inner growth. Mine is not a story of flight, but it’s a story of long distance, of the courage it takes to part from one’s roots while still remaining, somehow, connected—as it happens to the unnamed character of “Her Kind,” which dreams to be attached to a pole and runs until sheer momentum lifts her from the ground. Though she’d like to be a bird, she knows she’s not one. Still, she stubbornly enjoys her parcel of levitation.

After all, my book ends on something aerial as well: the airmail letters, light as feathers, going back and forth across the Atlantic, “fragile threads creating the legend, stretched over oblivion.”

Bird of Ashes and Fire: Toti O'Brien reviews SURVIVING HOME by Katerina Canyon

There’s a holiness to this poetry collection, as boldly and blatantly secular as it is. A profound, human holiness.

“Here is my pain,” says a poem from Katerina Canyon’s newest collection, Surviving Home. “Consume it.” And it ends, “Then do absolutely nothing.”

Canyon’s pain, stark naked and shining, is what the book unveils for the reader. Without a single doubt, it’s a pain that inherently resists consumption. It’s the pain of the Phoenix, bird of ashes and fire, lava and resurrection, introduced as Canyon’s spirit-animal in a poem that adds to the intensity permeating all verses a sudden, bright vein of humor. This Phoenix has short, black feathers and looks like a stubborn chicken, pecks at bugs and roosts on the windowsill of a hospital room. Where else should a Phoenix be? Barely reborn, yet soon bound to burn again—as like Icarus, she can’t help flying towards the sun—it isn’t someone’s chimera. It is the real thing.

So, what does resurrect from its own ashes? Is it the poet? The poetry? Is it memory? Is it pain itself? I believe what is meant to stay is the inextricable mesh the book is made of, the tight tapestry of suffering and resilience, experience and reflection, witnessing and rebellion.

“Here is my pain,” Canyon writes, and there’s a holy echo to her words, as if she were hoisting a calyx and saying, “this is my blood.” The same biblical quality is found in the first poem, “Involuntary Endurance.” Since the opening lines, “My story is not one revealed with chapter / And verse. It is expressed in blood and bone,” a new genesis is announced. The word becomes flesh.

Sparsely, yet throughout the book, the poet carries a conversation with the kind of god who is a white, male, supposedly loving father. The dialogue is a peer-to-peer exchange. Canyon doesn’t forgive this god who allows pain to be widely and unevenly distributed. She looks straight in his eye, unafraid to let him know she doesn’t abide by his rule. As the book proceeds, we feel that the balance between human and divine shifts, that the girl who talks back to god wins the argument, takes things into her hands. And we trust her. It is she that we now believe. There’s a holiness to this poetry collection, as boldly and blatantly secular as it is. A profound, human holiness.

What pain is this? Societal gravity funnels pain so that the heaviest burden weighs on black women. Even more, depending on when and where they are born. Add childhood, and you’ve got the vantage point from which Canyon writes. So the pain she refers to is the agony endured by the square inch of skin, the inch cube of female/black bone that supports in its whole the magma of the world.

Still, with the sheer honesty that is her true signature, the poet manages to shun the spotlight, identifying a locus of more suffering. In one of the indelible poems she devotes to her younger brother, she talks about whiplashes. “I just remember / Twitching as is each crack were / Against my back

But they were not. I am just a witness.

I hover through storms and report

The heat index of memories.

Father’s whip stopped when the scream of the child stopped. This is the brother to whom the book is dedicated, the boy who’s locked inside a closet all day when he howls his bothering “rabbit scream.” The elder sister is sent in as well, “as a sedative.” The routine is narrated in a poem that is central to the book both physically and metaphorically. The dark closet where the siblings are bundled and confined is a womb in which—like the phoenix—they will find a way of being reborn. Rather, to re-create the world they unwillingly were born into. It is the alchemic athanor allowing them to transform the one thing on which they have control: their perception. Their imagination. There, in captive suspension, paradoxically they will find inner freedom. They will turn the world on its hinges, like an afterimage, and decide the cell in which they are entombed is an open, luminous immensity.

Perhaps.

Father-with-the-lash, father closet, father shark, father snake has no mercy and the book has no mercy on him, yet doesn’t pronounce verdicts. Father is a dispenser of pain, a main instrument of pain, yet a vehicle too, as pain passing through his hands is bigger than he is, and comes from further back, elsewhere.

Also strength and resilience come from far. Among Canyon’s most moving poems are those highlighting vertical legacy, the lesson of black women from the past (“Sojourner”) and especially the mother-daughter, mother-son bonds. From “Playing with Roses”:

Your talent resides

somewhere within me

Memory is enough

to make it bloom

[…]

We are daughter and mother

Bound by the same sanguine root

From “Before God”:

When you cried, I nursed

you in bitter milk.

Breaching through secrets,

you asked

if I ever wanted you.

Shouting through clouds

My son, I wanted you

before my own birth,

Before first sword cut to stone.

Bathe in my tears, my blood

Know that I wanted you

Before God.

Love legacy is so deeply felt and expressed, it seems to imperceptibly lift the overwhelming weight of abuse. At least show another path, another perspective.

A few poems touch at language in interesting ways. From “Scrabble”:

[…] Some letters are

worth more than others. Some words

worthless, as the tiles reveal.

[…]

When it’s over, I’m left with a blank.

A long conversational poem (“I Left Out ‘Bells and Whistles’”) enumerates words and expressions coeval with the poet’s birth (from “magnet school” to “assault weapon”, from “black-on-black” to “delegitimize”)—a smart, subtle way to show how heavily an era-and-society’s clichés affect those they directly concern.

In a similar way, this collection made me ponder a trope of our present time—“trigger”—all too naturally associated with Canyon’s powerful poems. Content triggers. I am often perplexed by their practical application, but this book made me doubt the concept itself. Made me ask how legitimate “triggers” are, when it comes to poetry. When it comes to this.

She says, “Here is my pain.”

Look and listen. Then, let it resonate.

"Bleeding Roses," the poetry of Adeeba Shahid Talukder

Shahr-e-jaanaan: The City of the Beloved, is Adeeba Talukder’s first full-length poetry collection. As the author states in her preface, all the poetry contained in the book occurs “in dialogue” with the Urdu tradition of Ghazal, which Talukder has studied and translated for years.

Shahr-e-jaanaan: The City of the Beloved, is Adeeba Shahid Talukder’s first full-length poetry collection. As the author states in her preface, all the poetry contained in the book occurs “in dialogue” with the Urdu tradition of Ghazal, which Talukder has studied and translated for years.

“Dialogue” pertinently defines the complex interplay of Talukder’s creation with its literary sources. Such meeting takes a number of forms, from translated or rather “transcreated” quotes to reinventions of entire poems, from tributes to famous authors to the borrowing of traditional characters, imagery and tropes.

The universe of Ghazal freely and fluently inhabits the page, self-deciphering as the reader proceeds, without need for punctual explanation. Although, at the end of the book the author clarifies her references, giving context to the authors she quotes as well as to the characters that she borrows from them. To revisit the book after reading the final notes is a different and worthy experience.

*

But what really counts is obviously the first reading, the one before the notes. Ghazal originated in 7th century within the Arab tradition, later spreading to Persia, Turkey, and the entire Indian continent. Its theme is unrequited love, as a combination of shrill pleasure and unbearable suffering, with its trail of grief and insanity. It is the kind of love we find in the Song of Songs, in all mystical literature and, slightly tamed, in Medieval Courtly lyrics. The language describing it is quintessentially ecstatic, inextricably mixing the spiritual and the sensual, an explosive collusion of carnal and divine.

“Shar-e-jaanaan” is bravely themed after this type of love, which Talukder lets detonate through the pages, allowing it to bounce back and forth a thousand of years, across continents and civilizations, without losing a drop of intensity.

*

The book is articulated in sections titled after Ghazal tropes such as wine, the nightingale, chains, dancing courtesans, the tearing of the clothes, and more. Characters and motifs, though, don’t abide by such grouping. They make loops, go underground and reemerge, circulate at leisure, as if those partitions were loosely drawn Tarot cards, ready to be shuffled again.

The imagery Talukder sifts from Ghazal and then makes her own truly recalls ancient Tarots, even sharing their colors (red, black, white and gold), as well as it evokes European folktales, which of course weren’t European to start with. They condensed East and West as they gathered, preserved and passed down a legacy of symbols drawn from the collective psyche.

The echoes of those tales, not even consciously acknowledged, amply enable the western reader to appreciate “Shahr-e-jaanaan” without mediation.

*

For example, the opening poem, a prelude to all sections, coming back in a different version at the end of section v, deals with reaching womanhood with all that such passage entails. As she realizes she no longer can “wait to be beautiful,” the poem’s speaker pushes “bangles upon bangles” onto her wrist, rubbing her “hands raw with metal and glass.”

Each time a bangle broke, I watched

the blood at my veins

with a grim face

feeling more like a woman.

If the wrist is a trope of Ghazal poetry, symbolizing, the author explains, female fragile elegance, so are bangles, dancers’ most typical ornaments. But the association of female pre-nuptial adornment with self-mutilation is practically universal, as is the ambivalence of desire for sex and abhorrence for the loss of freedom and integrity implied by marriage.

So the blood profusely spilled throughout Shahr-e-jaanaan, namely or else in the shape of scattered rose petals (a literal, constant “defloration”), rusty leaves, henna stains, is both menstrual blood and blood of lost virginity, the same bled by all little mermaids when their tail is split into legs. We easily recognize it.

Moreover, wrists like ankles are to the human psyche portals through which bad and good enter our core in order to heal or destroy it, and the same is true for the neck from which Majnoon, a Ghazal character to whom Talkuder devotes many poems, repeatedly tears his collar, shedding basic protection, making himself a pray because of despair. Majnoon is the fool, the one who has lost his reason for love.

And the bangle, the bracelet, is just the first loop of the chain it stands for, the signifier of slavery.

From section viii, “God-shaped Woman”.

… To be a slave:

the pull of light,

the chain’s idle

bind.

So the love addressed by Ghazal poetry, Petrarch’s sonnets, mystic literature, great Romantic novels, the Song of Songs, and by Talkuder, wounds or exacts self-wounding, forces its way into the heart, maddens and enslaves.

It’s a passion we are unable to negotiate because we are too young (it is love seen by the adolescent as the fate life will force upon her) or because our psyche was crushed within the jaws of some binary, smashed by the irreconcilability of pleasure and guilt, gain and loss, want and fear.

Such tornado has multiple facets, some more pleasant than others, as it implies fusional stages and the exhilarating blur of self-boundaries, as it swings between the polarities of rejected suitor and omnipotent beloved, which of course are two sides of the same coin, a mirrored reality.

*

Shahr-e-jaanaan isn’t afraid of exploring contrasting refractions, as if perhaps an ultimate meaning could spring forth from their constant shuffling. What certainly emerges is a questioning of the whole mythology, a deep, open meditation made of shattered fragments, as if the poet had first smashed a mirror and then randomly picked shards, holding them to the light for readers to see what each reflects, finally recreating their own vision.

In the first poem of the book, the bangles have “no symmetry or sequence.” Their colors are “bright, jeweled, and dissonant”.

From “Kathak: The Dance of the Courtesans:”

… You, fragile

as glass, will learn:

you were made to break.

Should a poem be selected to epitomize the collection, a sound choice would be “When in the dark / my mind brightened.” It begins the book with striking imagery, gathering in one take the cruel rite of passage later articulated section by section. It brilliantly returns at midway, and dialogues with itself.

Also the title poem, which alone forms section vi, would be a natural choice. It describes the speaker’s admission into a mental ward, following a breakout that turns into a breakdown. Here as elsewhere, Ghazal verse and tropes seamlessly meet the present tense, traveling at the speed of light from remote ages to the now, instantly incarnated, made flesh.

My personal choice is “On Courting Calamity,” a brief poem found in section iv. Rather than exemplifying motifs, it highlights the book’s modus operandi and deeper intent. It expresses a need for joining extremes, such as an old tradition endowed with immense beauty but carrying a mortifying ideology, and a present where the ideology no more applies but the beauty deserves to live. It yearns for reconciling opposites in general, those antinomies that if not harmonized lead to insanity, such as the desire to be loved and the fear of being annihilated, the compulsion of abiding by the myths of beauty and simultaneously denying them. These conflicts are explored throughout Talukder’s verse and they materialize in the body, which they inhabit and haunt, pulling it apart, tearing at its core, unless words find the power to extend themselves over the chasm, to bridge through.

A thread

from pre-

eternity

to past time’s

end, a thread

that binds

movement

to gesture, a crow

to a narcissus.

I stretch.

My waist, this morning,

is a knot.