An Interview with Sheldon Lee Compton

So, you establish this grave sense of danger, and this insular need to protect self, family, and to defend against that ‘evil’ at large. Willing to address this? Is this a recurring theme in your work?

Robert Vaughan: Hey buddy! I was up in Boston over the weekend for Tim Gager’s DIRE literary Series and I fell into a time warp. Good news is I was able to start reading your book, The Same Terrible Storm. Man, can you write! I’ve always been an admirer of your craft. We’ve crossed paths in many different places online, and off. But I was drawn into your stories immediately, and can’t wait to dive into the interview. Such an honor to get to chat with you about this heavily awaited book. So, let’s start at the beginning. How long have you been working on this? How many drafts? Tell me about the progression of this “final” birth of your book.

Sheldon Lee Compton: The Same Terrible Storm is a collection of stories completed over the period of about three years, many of them published in some generous literary journals and others just now seeing the light of day. Of the stories in the book, I’d say I put each through three or four drafts for the longer stories and a couple for the short-shorts. This was a decision that came fairly late after talks with Stephen Marlowe at Foxhead Books, the press that published the collection, the idea to include both long stories and shorter stories in this collection.

I can’t say how happy I was to have a collection on hand for Stephen when he and I first talked about my sending something to the gang at Foxhead. I sent two collections – one that became The Same Terrible Storm and a second titled Where Alligators Sleep, which is exclusively short-shorts. I had a lot of input on the book itself, from the final content to the cover, which was handled by the talented Logan Rogers and his crew. My plan for the next collection is to add several short-shorts before publication, maybe even double the number of stories currently in the submitted draft.

RV: Sounds like such a dream come true. Also, this organic process you describe (varying lengths of stories turned into a collection or anthology) seems to be more common currently. It’s great that you had such a supportive team at Foxhead, makes me thrilled to hear this score for indie presses. I wanted to discuss your opening story of TSTS, I was so immediately captivated. You build such a fierce, tender relationship between the narrator and Mary, and son, Dennie. From page 5:

‘I don’t even like insects to bite her. That’s how personal I take it.’

Also: ‘But Dennie was to be raised Christian and that made learn- ing hand-to-hand combat maneuvers tricky. Self-defense didn’t fit into Mary’s plans all that well. But she knew the world was mean, cruel and hard, so she left it alone. Only thing, she didn’t want to see Dennie coming at me with sweep kicks and throat strikes, so we stayed at the east end of the field, away from the house. I felt like I was in a familiar place out there in the field, just like in the war. It was those times out there with Dennie when I would go hours without a drop of anything, and not even miss the smell. If we could’ve stayed in that field forever, hand-to-hand, learning how to keep the world from swallowing us up, I might have had a better chance at being a good Christian.’

RV: So, you establish this grave sense of danger, and this insular need to protect self, family, and to defend against that ‘evil’ at large. Willing to address this? Is this a recurring theme in your work?

SLC: I for sure inject that sense of danger you’re talking about with most of my work, but I suppose it’s not always an evil-at-large type of situation. Often the danger is very focused. But, as anyone who reads the book will see, the stories are set in Eastern Kentucky and this region often functions as a character in its own right, and usually in opposition to the hopes and dreams of the people who populate my fiction. I’m not trying to make the place I come from worse than it is, but at the same time I’m not interested in sugar-coating anything, either. When I write about the people I’ve grown up with and live with now, most folks are of one of two mindsets — there are those who will argue that the mountains that surround are protection from the rest of the world, or those who feel the mountains are hardly more than prison bars, stopping any notion of improving our lot in life. This is a black and white sort of thing, and something I like to do is find the gray in those instances. It’s what I hope I’ve achieved in this book, nothing is completely honorable and nothing is without a certain amount of darkness. But if there is a consistent danger or opposition throughout my work it would be the character’s region. Whether you love the mountains or hate them, this region plays a huge role in the lives of most Appalachians.

RV: I love that you addressed the region, which functions as a character (in its own right) because I feel you have such eloquence in how you write nature and environment, how it shades a story. For example, from page 12: ‘Then the drizzle lifted off, back into the clouds, which moved away in a slow bulk across the ridge and dissipated like a swarm of colorless wasps.’ It is breathtaking, the imagery so poetic. I also admire your use of character names: Burl, Spider, Torch, Mackey, Murphy…how do you decide names? Do they decide you? Also, the “double” tag names with real and call names like Michael/ Spider and Caudrill/ Torch. Are names important? If so, how?

SLC: I’m thankful for your attention to my attempt at a certain lyrical style, Robert, I truly am. Two of my influences as a writer are Breece Pancake and Michael Ondaatje, whose styles could not be more different. Pancake’s is muscular and tight, while Ondaatje writes in that highly poetic way that always reveals the poet inside him. So my influence from Pancake was in how to write honestly about my region, while I tend to lean to Ondaatje as inspiration for the individual sentence, its texture, sound, feel and possibilities. I work hard at blending these two literary devices in my work, and so I do so appreciate when anyone notices. Nature is a given with regional writing, and so it’s more often the place where I can allow myself to use a more poetic voice, even if the story is about slaughtering a hog or working at a junkyard.

I do give a fair amount of thought to character names. There are so many colorful names where I’m from that I often find myself meeting people and then writing their names down as a reminder to later use them in whatever I may be working on at the time. Each one you’ve pointed to here were either names of people I met or worked with or heard of through some local source. Spider and Torch are actual call names of two truck drivers from Eastern Kentucky. Somehow I knew I’d use them in my fiction at some point. I simply couldn’t resist. One of my favorite character names was German — a character from an early draft of the story “Snapshot ’87.” I hated to edit that character out when revising only because I liked the name so much. It was taken from a guy I worked with in the coal mines when I was a teenager. It was his birth name. I still find that terribly cool.

RV: Names in general are cool! For instance, I love that you call me “hoss.” Even though you might call everyone this, I’ve often wondered if I ought to respond by calling you “little Joe.” With all brotherly respect, of course. Tell me a little about your writing life- do you write in the morning? Only certain days? Computer or long hand? How do you tap into a muse, or is that just horseshit?

SLC: Nothing but brotherly for you there, hoss, and feel free to lay some “little Joe” on me! The writing life for me is a full-time job and I’m thrilled about that. In October and I took the leap and left the workforce until very recently. While writing full-time I worked about eight to ten hours a day, waking at five-thirty in the morning and working through the day, allowing myself a couple breaks here and there and an hour for lunch. I found the old saying that it takes a great deal of discipline to pull that off is so very true. The upshot is that even though I’m back in the workforce, I can still manage about six hours a day of writing, doing most of the work in the early morning before I ever leave for my grunt work. Other than needing that instant gratification of the computer for the actual process, I don’t have many tangible needs to write. I once wrote in longhand, but since college my penmanship is simply too poor. I can write a note and if I don’t refresh myself before bed by going over it I’ll not be able to read it the next morning.

Like all folks in this craft, I gain my inspiration, if you can call it that, by reading. I can read a passage from Barry Hannah and get really pumped about trying to write that clean and naturally, or pick up books like How They Were Found by Matt Bell or Mel Bosworth’s Grease Stains, Kismet, and Maternal Wisdom and Mostly Redneck by Rusty Barnes, just to name a few, and be reminded that I actually know writers who are doing it right so it can’t be too far out of reach for me. Sometimes just turning other people’s books over in my hands and reading the blurbs is enough to remind me that this work can be done and done well. The trick for me as a writer of fairly heavy themes is to not take myself too seriously while doing it, though. I usually write about Eastern Kentucky, as I’ve said, and the people here. Most of what has been published until the last five to ten years about Appalachia has been a little too soapbox for my tastes. It’s difficult to write about a culture and keep social commentary out of the picture, but I hope I’m coming close by concentrating on the characters and simply telling their story in an entertaining and compelling fashion.

RV: In your last response, you touched on the subject of themes in your work, referring to yourself as “a writer of fairly heavy themes.” In this collection alone, you broach religion, divorce, drinking, single parenting, blue collar jobs (and unemployment), lies. Can you tell me what draws you to what you write? Does it come organically, or are you turning life into fiction (to draw from Robin Hemley’s great book about craft)? Do themes come to you as you craft a story, or are you aware in advance of what you will be delving into for a certain story? Also, where do you find the motivation for your stories? You mentioned the Appalachians and breath-taking region in which you live, is there more? Maybe give us a tale not yet written . . . what’s something you’ve not yet explored and why?

SLC: I do draw on my life experiences in my work. Not as much as some might think, but a fair amount. I’m sure we all must to an extent. But, admittedly, I’ve happened to have had an interesting life so far, though most of it has been a darker, more difficult, span of time than some others. I was never really very aware my themes tended to be “heavier” than others until readers began making mention of it here and there. I was aware there were good writers and great writers out there who were not writing about the unemployed, single-parenting, divorce, drinking, the confines of religion, and so on. Just as much as I was aware there were writers, like myself, mucking around in those waters and mudholes. I don’t feel so much drawn to write about the subjects I take time to consider long enough for such a thing. I just believe strongly that each person, no matter if they’ve lived next door to one another for fifty years, have their own vital and unique way of seeing each and every thing and person around them.

I’m fascinated by that fact, and even more fascinated and eager to discover what my experiences look, feel, taste, sound like in only the way I can experience them. In order to truly do this, you have to share it with others in whatever you can. It’s funny you should mention if there are any tales I’ve not touched on yet, because there most certainly is, a glaring one, in fact. My maternal grandfather, Bob. He died when I was about four, so never really knew him. I knew he grew up as an orphan and lived by plowing fields for supper and other chores for a bed to sleep in. My family has always said the community raised him. It created in him a strange sense of looking out for himself, much to the hardship of others, especially his wife and children. He exists only in story form to me, and the stories are countless, an absolute well of stories. In all the years I’ve been writing, I only recently started a story based on him. It’s called “The Favor” and should appear in Where Alligators Sleep, if all goes well.

RV: I look forward to reading that story about your grandfather, Sheldon! Let me ask if you ever judge your work, while crafting, or even after a piece has been published? I recently sent off 24 poems to Gloria Mindock at Cervena Barva Press for my upcoming poetry chapbook, Microtones. And right after I clicked the “send” button, I experienced these deep pangs, like she is going to hate them! (good news, apparently she didn’t!) Do you go through this? If so, how?

SLC: I love that you’ve got a chap coming out, hoss. Hats off on that note, and that’s a fine title, too. As for judging my own work, well, you better believe it. Oh, yeah, man. I judge harshly. Old West hard. I can, in all honesty, say I’ve only written five or six stories I knew were good stories at the time I finished them. And like any of us who’ve been working it that long, you’re talking hundreds upon hundreds of stories. Twenty-four years and that’s it. Five or six stories, maybe. Of the two novels I’ve worked out of me like rotted teeth, I threw the first in a creek behind my house, the only copy written on my first typewriter when I was nineteen, and the second, which is good but needs a few major surgeries, remains trunked. It’ll see the light of day, though. As long as I know it’s good, I’ll keep working to see if it can be better. The others, the stories, became tolerable after several drafts, enough drafts that I eventually never wanted to read them again. That’s how it goes, sometimes. Work it until you drop. Somebody will notice. They’ll see how you’ve sweated and heaved and pulled and pushed and never let up. That work will show in your words. And it’ll show if all you did was sit back on your thumb, too.

RV: I thought you were going to say, sit back on your keyster! Hahaha. Okay, I’m going to mix things up now. Time to get off YOUR DUFF, little Joe. Here is a line from a recent Tin House New Voice novel, Glaciers, by Alexis M. Smith: ‘She decided against washing her hands.’ Write a 50 word (or less) piece using any or all of that line. Go!

SLC : Ha! Off my duff I come! Here goes nothing:

“The carpenter held her fingers, the last load of old shingles already hauled off. He stayed on awhile after, picked the yard for torn pieces of the old roof and nails. She sat on the porch while her carpenter softly parted blades of grass. She decided against washing her hands.”

RV: Nice use of white space, very provocative, too. Okay, you’re on an island in the Pacific looking for Amelia Earhart’s remains. Name five different parts of her body and a favorite song you are listening to at the time you discover said part.

SLC: Okay, let’s see here – Crossing a small creek while listening to “Take It On the Chin” by William Elliott Whitmore, I find her jawbone, strong and determined, even in that tiny vein of water. Later, along a ridge north of where we came ashore, I trip across her leg, the boot laces still pulled tightly into an impressive knot. I’m listening to Townes Van Zandt’s “Flying Shoes” while admiring the sturdy boot and the leg that had flown so high for so long. I grow tired after several hours and find a shanty of some sort made of slim branches and great leaves spreading out for a roof.

As I enter, listening to Tom Waits’ “The House Where Nobody Lives,” I find a large stone. Along the side of the stone is a single fingernail seemingly embedded into the rock, seemingly still clutching for purchase. I’m about to heave when I leave the leafy shanty and lose my footing, sliding several yards into a clearing. At my feet I see what at first appears to be a dead animal, its fur matted and clumped. The closer I come to the thing I see its hair, a half inch of her scalp stretching across its underside. The Pixies “Hey” finally rolls through my ears. I can still hear that distinct cry of the guitar as I make it back to the shore line. I’m the first there, so there’s no news to share. I walk the line, listening for the others when a foamy wave moves in over my ankles and then out again. And now she’s looking at me. Those eyes, blinding if stared at for too long, pushed back from the sea and onto the shore of her private and expansive cemetery. And as I look at her eyes, and only her eyes, Hank Williams is there singing “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry.” And I do.

RV: Dang, Little Joe, you’re good. I say, expand and submit that one! Now, I will give you a “word bank,” five from Matt Bell’s new novel, Cataclysm Baby: empty, scars, soot, taste, & swallowing. You can use any or all of them in a 50 words or less piece.

SLC: I’ll tell you something, hoss, those are some fun words to throw together. Here you go: The room is empty as scars without stories when Ben wakes. It is a knocked about box made of soot, and, as he feared, most of the food burned along with all the hope left. Though he cannot taste what is not there, he continues swallowing as if in prayer.

RV: Great imagery there. You’re a natural born poet, my friend. I want to ask you about your online journals. I know you’ve started a few. You took my triptych, “A,B,C” at A-Minor when you were at the helm there. We also cross paths at Fictionaut, a member-only online writer’s community. Tell me how your writing has shifted since the advent and rise of online writing. Any positive or negative influences?

SLC: It was a pleasure to publish “A,B,C”, no doubt. Wonderful work. And, yeah, just realized I tossed in a rhyme without realizing it with the “there” and “prayer”. Well, well. Thanks for suggesting I have a little poetic notion. I think poets are on the front line in the literary world. To write and consider each word, each comma, each line space with such deliberation is something to be admired. To speak directly to your question, man, I cannot overstate how important the online communities of writers and what many consider the indie writing scene have been for me. With each small journal, print or online I either founded or co-founded, I received such satisfaction going through submissions and finding just the right story, the one I just couldn’t wait to read aloud to someone.

With Cellar Door, the first journal I co-founded, we didn’t go online. We paid for a run of two-hundred and fifty copies and sold them from the back seat of our car. We actually stacked the envelopes full of stories in the middle of the living room floor and parted them out into two basically even piles and started reading. That’s where I was first introduced to writers like the late Carol Novack, Matt Bell, and an already well-established Joey Goebel, and many others I never heard from again, but remember their stories as clear today as the second I read the first sentence of their submission. With online journals, I co-founded Wrong Tree Review and then, within the first issue, became interested in starting an online journal that offered readers something new each week. So, A-Minor Magazine came about, which I edited for about a year and stepped aside. I loved the experience, but am not currently involved with any journals. Of late, I’ve been a little selfish. I want to focus on my own work and simply enjoy the work of others. In the past week I’ve added seventy-four books to my wish list at Amazon, not to mention my drop-ins at Fictionaut, the writer’s community you mentioned. There’s always something great to read there. All in all, I would say the positives in the rise of online publishing greatly outweigh any negatives. I think print and online can exist, if not complement the other. People are always eager and pleased to find new options to communicate with each other, share stories.

RV: I like how you’ve worn so many hats leading to this new one: published author (of your new book: The Same Terrible Storm!!!) Explain how this latest transition has changed you, if it has at all. And who are the authors you’ve read lately? Any that stand out?

SLC: Shortly after I learned Foxhead accepted the collection, I made the decision to leave the traditional workforce and write full-time. That has been a major change, and a positive one so far. I’ve been working full-time at this craft since October with the support of my loved ones, and I couldn’t be more fortunate. The true blessing for any writer is to have people on your side who understand that it can be work, not just a hobby. It takes a certain type of person to realize this is a craft, a true pursuit of labor, without actually being a writer themselves. I don’t know if I’d be able to make that leap or not, but I’m thankful to be surrounded by those who can.

The daily grind of writing full-time is a fair amount more challenging than I’d expected, but it’s good work. It helps me to have a few projects going at the same time. Currently, I’m writing the novel and also working on a book of photographs with accompanying flash fiction pieces, each of thousand words, for a future book to be called A Thousand Words. My wonderful lady Heather McCoy is the photographer for the project so we’re getting the chance to work together. The hardest part at this point has been picking my favorites from her portfolio. At one point I had I roughly three hundred pictures sorted out and then realized that would be a pretty huge book at one thousand words each. We’re aiming now for one hundred photographs and stories.

I’ve also been buffering my work day with reading, so I’m glad you asked about what’s off my shelf and beside my laptop these days, Robert. Since I’m in novel mode, I’m reading more along those lines. On tap for now is Ron Rash’s Saints at the River, Tom Franklin’s Crooked Letter, Crooked Letter and a couple story collections with Kyle Minor’s In the Devil’s Territory and Chris Offutt’s Out of the Woods nearby, as well.

An Interview with Amelia Gray

Can you talk a little about what brought you to the book? What were the conditions that led to your picking it up for the first time, and why did you want to talk about it here with me?

For this series I’m asking the writers I love to recommend a book. If I haven’t read it, I read it. Then we talk about it.

In this installment, I’m talking with Amelia Gray about Airships by Barry Hannah.

* * *

Colin Winnette: Can you talk a little about what brought you to the book? What were the conditions that led to your picking it up for the first time, and why did you want to talk about it here with me?

Amelia Gray: This great book! I first found Barry Hannah teaching at Texas State, during my first year of grad school. I was 22, and here was this motorcycle-riding troublemaker writing the best fiction I had read in my life. Can you imagine? I couldn’t handle it.

CW: Oh wow, so you studied with him? How fortunate! Were these workshops? One-on-ones? How was it structured and what was it like?

AG: I sort of studied with Hannah. Really, I was a bystander for the others who were studying with Hannah. We were only allowed one workshop semester with a visiting writer and I figured I was a young idiot (I was right!) and that I should hold out for Denis Johnson in my last year. Still and all, I feel very lucky about it. I sat in on some one-off workshops and he was about how you might expect — feisty, intimidating, kind in his way. He was approachable. He liked to shoot the shit.

CW: It’s interesting, knowing your work, but not knowing before that you studied with Hannah, I would have probably listed him as one of your influences. Is there anything about your approach to writing, or even living, that you trace back to him specifically?

AG: One thing he said in a Q&A I’ve since quoted to other people a million times, to the point that I’m paraphrasing it, but he said that a story starts as a diamond in his mind, perfect in every way, and when he sits down to write, the diamond crumbles into dust. It crumbles a little more slowly as he gets older, but no matter how many times he sits down to write, it crumbles. That idea has always been a comfort to me.

CW: Some might say you can never recreate/re-present an idea, which occurred to you in a specific context, and in a specific way, so every time you sit down to write, you’re not destroying what was there before, you’re just not able to make it again as it was. You can’t. You’re making something else.

AG: I don’t think it’s willfully destructive so much as it is a simple study in the imperfect leap from brain to page. Like the lady who destroyed the fresco last month — she had an image in her mind and she did the best she could.

CW: When we were setting up this interview, you mentioned you only recently came to Airships. What was your initial reaction to this particular book? Did it differ from the work of his you read as a 22-year-old?

AG: Well, so I was young when I met his work, and so star-struck that I had him sign two of his books: Bats out of Hell and Yonder Stands Your Orphan. I was working my way through Bats out of Hell, reading his stories aloud to boyfriends, but I found I didn’t feel comfortable reading the book. I mistreat books, I break the spines and leave them face-down on the sink while I’m washing my hair and whatever. I wanted to read this book and mistreat it but I couldn’t bring myself to, maybe because he wrote in it and he was mythologized in my head. Every story he wrote was brilliant and changed my writing, and that was a little scary. I was afraid to break the spell. Then he died and I was too sad to read him for a while. Then, finally, recently, I was neither sad nor afraid. Turned out I’d read half the stories elsewhere so it’s not quite true that I hadn’t read it anyway.

What a book! What mastery in such considered writing that seems loose and funny! There’s so much life and air and love and light. I feel lucky that I didn’t read some of these stories when I was 22, that I saved their first experience for when I had the heart to appreciate it. I’m borrowing argument from the Catholic virgins here.

CW: Yes! There is irresistible heart at the core of Hannah’s stories, even the more brutal, such as “Coming Close to Donna.” I think it has a lot to do with the fact that he doesn’t shy away from love. Some kind of intense love is at the heart of almost all of these stories, and few writers other than Hannah can so boldly and confidently say something like, “Love slays fear,” (“Escape to Newark”) and make us really and truly feel it, while at the same time keeping it in voice, buried in the characters in the story, distancing himself from it. Is this something you’ve felt while reading, and, if so, can I ask you something as simple as, how do you think he does it?

AG: Yes, exactly. I’m glad I wrote that paragraph above about love and light before I read this one, because now I feel we are in a synchronicity. “Nothing in the world matters but you and your woman. Friendship and politics go to hell.” I suspect he does it because all of his characters have enough of him within them that they each can burst forth with this unique, authentic voice. He’s really writing the same story over and over again, his own heart, the song of himself, whatever you’d like to call it. That he does it so damn well is where you’ve got to sit up and pay attention.

CW: I’ve had this itch about Airships for awhile now, or a curiosity, and it’s about the way Hannah uses religion from story to story. It feels a little different each time, as if he’s approaching it from a variety of angles, and I begin to wonder about this personal relationship to religion. Having known him, what do you make of the biblical references scattered throughout Airships?

AG: Hannah had a near-death kind of experience right around the time I knew him and he told us that he found Jesus in that time. I think I remember him saying that Jesus actually came into to the hospital and sat with him. He wrote in one of my books: “Christ is the strength that you do not have to pray for. Thereness, my lass.”

CW: I’m tempted to let that hang, because it’s beautiful and strange and I really love your answer, but not knowing about your upbringing/your relationship to religion, I have to ask what that meant to you? His message, and his honest belief that he was visited by Jesus? Just as a reader of his work and a fan.

AG: I found it to be an honest belief from the man, the belief that he was visited by Jesus. I was raised in the Presbyterian church and have heard that stuff enough that I don’t find it that strange. I hope that if Jesus ever visits me it’s cool hospital Jesus and not freaked-out jail cell Jesus.

CW: Is there a story that best exemplifies, for you, what this collection can do? Is doing? I think of a story like “Testimony of Pilot,” its range, the strange violences, the characters brutalized by love and the mere passing of time, it feels like this story shows so much of what Hannah is capable of, and he seems so completely in control of all of it. It feels vast and airtight.

AG: Actually I was thinking ‘Testimony of Pilot’ too. There are others that are tighter in terms of plot but I just love ‘Testimony of Pilot” for just that organized appearance of chaos. “Appearance of chaos” instead of “chaos” because there is that work there, yes, though the seams are all stitched tight. And it has one of my favorite lines of all time.

CW: Not to ruin it for those who haven’t read, but I’m guessing it has something to do with a dragon?

AG: Oh yeah, you got it.

CW: There’s a brilliant move in TOP, where Hannah allows his narrator to get sort of out of control, to work himself up to a frenzy — I’m thinking of the recital led by Quadberry — and (credit where credit’s due, Adam Levin first pointed this out to me in a writing seminar at SAIC) Hannah acknowledges it, owns it, and sort of cuts right to the heart of how storytelling works and why we bother to do it. The narrator gives us a nod, after it’s all said and done, and he admits how memory distorts and that he got carried away. He’s mythologizing. What are your thoughts on that reading? Is Hannah writing this self-reflexively? And where else does he exhibit these kinds of acrobatics?

AG: That recital scene is exactly what I’m considering when I think of the appearance of chaos. It feels out of control because we’re not used to that kind of structure in a long story like this. It reminds me of some other writers, ‘How to Tell a True War Story’ by Tim O’Brien, parts of Train Dreams by Denis Johnson.

CW: What’s your position when it comes to control over a story? Do you let a story run away with you, or is each piece carefully plotted beforehand?

AG: Every time I write, I’m trying to run away from the careful plot, but the plot drags me back in. It’s like one of those bungee runs or the third Godfather.

CW: If you could only recommend one story from the collection?

AG: ‘Love Too Long’ gets me every time.

The Way I Sleep Is Sporadically and Often Desperately

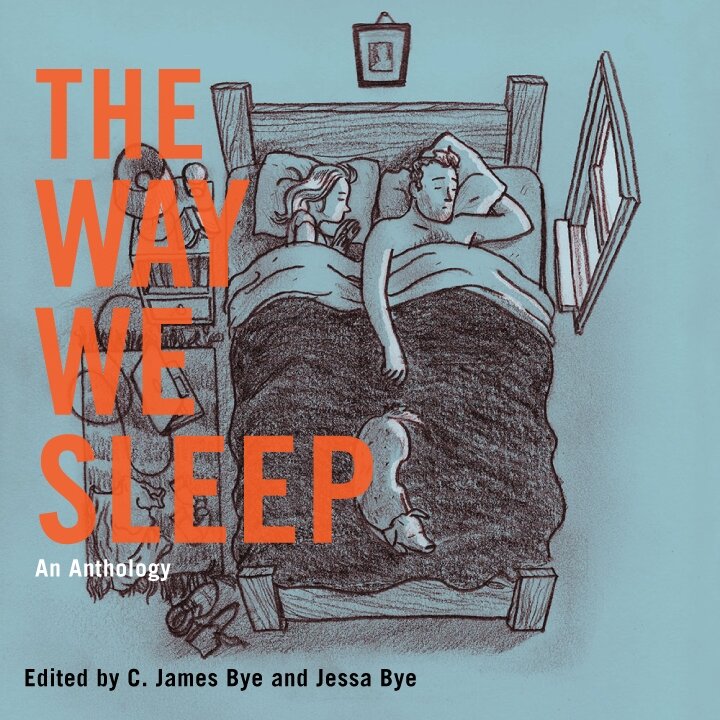

The Way We Sleep really covers everything, even the things that haven’t happened to me. It’s beautiful and grotesque and touching and tragic and funny and playful and philosophical and magical.

If you were to see my bed or even my bedroom, it might be hard to think someone sleeps there. Books, paper — so much paper just somehow everywhere — clothes, letters, those envelopes and boxes people mail books in, Gameboy Advance games — only Pokémon, really—a toothbrush, pens, used up batteries, and all kinds of random cords that belong or once belonged to something I needed. The way I sleep is sporadically and often desperately. Somehow, The Way We Sleep captures all of this and so much more.

I don’t like anthologies and have maybe read one or two before picking up Jessa Bye and C. James Bye’s The Way We Sleep. Knowing I had a deadline to read this, I was not looking forward to it. Dreading it, really. Anthologies or even just normal short story collection can take me months upon months to get through and so I was expecting to have to send some disappointing emails this week, explaining I was still only on page 20. But then just three sittings later, it was all over and I was shocked by how quickly it went, how easy it was, how beautiful and painful those pages were.

I have had a very tumultuous relationship with sleep and my bed. Dreams, though, we’ve always been on the same team. But the bed, it can be a lonely place, often a haunted place, a crippling and emotional place. Now, if I were to try to explain what my bed means to me, I’d probably just hand someone The Way We Sleep. It really covers everything, even the things that haven’t happened to me. It’s beautiful and grotesque and touching and tragic and funny and playful and philosophical and magical.

The writing in here is mostly top notch, with my favorites being by Roxane Gay, J.A. Tyler, Etgar Keret, Matthew Salesses, Tim Jones-Yelvington, Margaret Patton Chapman, and Angi Becker Stevens, whose story was my absolute favorite and the one I still cannot stop thinking about. There are a few stories that fall short, but this book is really full of amazing things, and for every story that misses, there are five that hit in ways you never imagined.

And it’s not just full of short stories, but also quick and funny and weirdly insightful interviews and comics. The comics were one of my favorite parts of the reading experience. Right in the middle of the book, it works as a sort of breather from the prose. Playful and funny and emotional, the comics really rejuvenate you and make it so you need to keep reading. For me, even more than that affect is the fact that I dream weirdly often in cartoon. I mean, to see my dreams reflected in a book is one thing, but to see them drawn out is really something else. Something deeply satisfying and beautiful.

The Way We Sleep just works. Maybe it shouldn’t, but it does. Jessa Bye and C James Bye have done a tremendous job here, because editing a book like this is much more than simply checking grammar. The structure and juxtapositions of this book make for an extremely gratifying reading experience and allows the pacing to never get bogged down by similarity of content or tone or style. This is a collection of stories, comics, and interviews that just speeds by.

Being released just in time for the holidays, I can’t recommend it enough as it would be perfect for friends, lovers, and family. There’s something in here for everyone, whether they’re looking for sex or love or humor or just something to pass these cold wintry nights.

So, yes, The Way We Sleep is something you want to read. But be sure to keep it next to your bed, just in case.

Skinlessness: An Interview with Kim Parko

In times of confusion, it is best to stay in the pocket of a bigger animal. There you can be alive and safe in a confined, dark space. Pick a pocket that is only slightly larger than you are so that you can move around a bit.

In times of confusion, it is best to stay in the pocket of a bigger animal. There you can be alive and safe in a confined, dark space. Pick a pocket that is only slightly larger than you are so that you can move around a bit. Pick an animal that is kind and will not eat its young if its young appear to be sickly. Your confusion might be mistaken for sickliness. When you’re in the pocket, just stay curled up. You might even want to suck your toes. Don’t wear clothes in the pocket; the pocket will serve as your clothes. The pocket will keep you warm in winter and cool in summer. Hopefully the pocket is worn over the animal’s heart. You will hear only the noise of the heart. You don’t want to bring your pocket radio, because all you need is the noise of the heart. If the animal’s heartbeat quickens while you are in the pocket, stay calm. Now that the animal is holding you, she will protect you with her life. If the animal falls to the ground and you notice the pocket growing cold, peek your head out and look carefully around you. Has the danger passed? Are there any other animal pockets for you to crawl into?

—Kim Parko, from Cure All

Megan Alpert: The character in the first part of Cure All was so vivid. As I moved from poem to poem, I felt like I was reading about this person who was unique in her sensitivity to the world. And then later, in the poem “Rapist,” when she finds a way to cure the rapist, rather than running from him, I felt that I was reading about the grown up version of the girl from the first several poems. In the book, when you use the word “I” is it always the same “I” or are you drifting in and out of different characters?

Kim Parko: I think that it’s the same in the sense that I have this sort of central character that’s often at the base of what I’m writing about. But it’s not like I’m thinking “This is Patty and this is what happens to Patty here and then this happens to her later in life.” It’s not that kind of character. It’s interesting, though, what you said about her being extremely sensitive — that’s something that I work with a lot and that’s probably a reflection of my own understanding of being in the world the way I am, that is just naturally coming through this character. And so I think when I put that character, that persona, into extremely difficult or painful situations, it’s a way of grappling with how it feels to be that kind of a person. So the “I” doesn’t necessarily always have to be the same person, it’s more the essence of what that character is running through those personas in a very fundamental way.

MA: The situations you put her in are painful, but she always seems to survive them.

KP: Yeah, I think it’s about trying to show how overwhelming or harsh the world can be if you’re especially sensitive. And that it’s not really a weakness, it’s not about an idea of victim — I mean there’s some sort of power in that sensitivity as well, so that that character can feel a lot and can be overwhelmed and can go through intense emotional states but that at the end, it’s just a rawness of dealing with the world and ultimately being able to survive it. And what that experience brings to one’s perception of the world.

MA: How did the book come together? Were you always writing these pieces as part of a whole work or did you gather together disparate pieces of writing? Did you always know that the book was going to be about cures?

KP: I’ve always been interested in the idea of the body. The body is so easily broken and so vulnerable to the physical world. When I was five, my favorite book was a book of skin disorders and I used to love going through it and looking at the pictures. So I’ve always been fascinated by what can happen to the body and ways that the body can heal.

In terms of the way the book was put together with the interludes of different cures, the interludes were part of the structure I submitted to Joseph Reed at Caketrain. We worked together on some of the organizational scheme and on creating some cohesion with the characters and settings in the individual pieces.

MA: You have an undergraduate degree in fine art and you work at the Institute of American Indian Arts. Has visual art influenced your writing?

KP: Definitely. I’m extremely visual. It’s easy for me to conjure up these worlds and I see them very vividly. Visual art can be frustrating to me because it’s a lot harder for me to create that internal space than it is with the written word. With visual art, I’m much more limited in what I can actually create. When I draw, it’s a similar process to writing in that I usually start with a line or a form or a shape and embellish from there without any preconceived idea of exactly where the piece is going to go. It’s similar to my writing in that it always ends up being a form or a creature or world. But with writing I can create a much larger scope. It can take me hours and hours to draw one of these creature-forms I’ve been working on, whereas my writing is just populated with all these creatures and settings.

MA: I’m thinking of your poem “Push,” where a girl grows green fur on her breasts. There are so many weirdly strong images like that in Cure All. Do you ever start with an image and feel uncertain about whether it should be a poem or an object of art? Do you have to work your way through multiple art forms to find out what something wants to be?

KP: Lately I’ve become much more interested in mixed media performance renderings of the stories that I’m working on. I’ve done some costuming and some performing of the scenes in the manuscript I’ve just finished. So I’m working on how these different modes of expression are interrelated for me and how they might have a much clearer relationship. Through turning my characters into visual art, I gain a stronger understanding of them. So if there’s a character that has some sort of strong physical attribute that you wouldn’t normally see in the “real” world, I have to think how will I translate that, how will I make it into a sculpture or costume or an actual object of art.

MA: In several poems you mention a character or object called The Curtain. Could you talk a little bit about that idea and where it came from?

KP: Something that I work on with my writing is the idea of an all-powerful being—God or whatever, just the notion of that sort of existence and what it means to my existence. The Curtain is the thing that is obscuring what’s really there, but it also is what’s really there. So it’s both things. It’s the boundary, but it’s also the thing beyond the boundary.

I often grapple with that idea, seeing what is beyond this reality, what is beyond what I can observe or see. I really like thinking about it. In my newest work I have a character called No One In Particular. People are always asking No One In Particular these questions and No One In Particular is always not answering. But it’s present. Just because it’s been named, it’s there.

Something About KA-BOOM: An Interview with JA Tyler and John Dermot Woods

No One Told Me I Was Going To Disappear combines writerly with painterly, harnessing the energy of a natural formal conflict and resolving it toward the common purpose of so much art—the love story. No One Told Me I Was Going To Disappear tells us a great deal. Not only do we find a story in which to lose ourselves, but a lesson in the nature of story-telling itself.

Stories, like the universe, are born of conflict. Electrons combine and collide, energy is born, KA-BOOM. Characters shout or sexualize, murder or meddle, KA-BOOM. As readers, we yearn for the KA-BOOMy climax. We lose ourselves in 800-page novels, needing to know what happens next. That’s narrative.

Sometimes a conflict is born off the page, between the reader and the words. The reader doesn’t quite comprehend what’s written, stops reading, thinks, and then, KA-BOOM. The reader emerges victorious over the un-understanding.

Like this, conflict makes us smarter, too.

So — here’s a Picasso quote with which I found myself conflicted:

“Often while reading a book one feels that the author would have preferred to paint rather than write; one can sense the pleasure he derives from describing a landscape or a person, as if he were painting what he is saying, because deep in his heart he would have preferred to use brushes and colors.”

I opened No One Told Me I Was Going To Disappear believing all art forms equally valid. But, like Picasso assumes above, still in conflict with each other. While painting beats writing for Picasso, most writers, I believe, will disagree. Because — KA-BOOM — writing is the most versatile of forms, a kind of code that worms into the hard-wired emotions. No matter how beautiful the painting or song, language can match (or exceed) it. (As a writer with no talent for drawing and deeply imperfect pitch, I have to believe this).

But in this extraordinary piece of art, JA Tyler and John Dermot Woods refuse the matter. No One Told Me I Was Going To Disappear combines writerly with painterly, harnessing the energy of a natural formal conflict and resolving it toward the common purpose of so much art—the love story. No One Told Me I Was Going To Disappear tells us a great deal. Not only do we find a story in which to lose ourselves, but a lesson in the nature of story-telling itself.

KA-BOOM.

*

Over the last few weeks, J.A. Tyler and John Dermot Woods were kind enough to elaborate.

JOSEPH RIIPPI: You likely won’t be surprised that what I want to begin asking about regarding No One Told Me I Was Going To Disappear is the relationship between the text and artwork. Can you talk a bit about that relationship with regards to the writing of the book? How much did the art inform the text, and vice versa? Were the artwork and prose created simultaneously or responding one to the other? What can you say with regards to your being “co-authors” as opposed to author and illustrator?

J.A. TYLER and JOHN DERMOT WOORDS: No One Told Me I Was Going to Disappear is a novel composed in art and text where each individual piece of art is a new chapter in the story, and each individual text is likewise a new chapter. But in terms of how the book as a whole was created, it was very much a dialogue between artists. Once we had struck a deal to do a project like this, which mostly consisted of a few emails saying “Want to do this?” and “Hell yeah,” John composed the first piece of art, the opening chapter, and sent it to J. A. Tyler. Tyler then wrote a piece of text as a response or conversation with that piece of art. When Tyler was done, he sent that text to John who would then compose a new chapter of art as a response to Tyler’s words. We did this, back and forth over the course of nearly a year, and the result was a co-written novel, a book that we believe is pretty unique in that it isn’t illustrations for a text and it isn’t a graphic novel, it is a collaborative narrative told in two mediums, by two authors, one chapter at a time.

JR: There seems to have been a conscious decision on your part to keep the artwork on equal terms with the text, too. The first and last chapters of the book, for instance, are pieces of artwork. Can you talk about that decision, to introduce your reader via artwork as opposed to language?

JATAJDW: It wasn’t exactly conscious to begin and end with art. John started the story and he decided to draw something. We also found an end in a chapter that happened to be drawn. We were interested in the narrative possibilities of words and images working together, but not in the more organic mode of comics in which they occupy the same space. Once we finished the book, we were pleased at how complementary the two storytelling approaches are. There is certainly no impression of ‘illustration’ or ‘captioning’ in this novel. It does seem that despite our increased ability to interact with non-textual work, images still largely work as inessential elements of literature (as ‘added bonuses’ or as a marketing element). We’re glad that No One Told I Was Going to Disappear functions as story told in words and told in pictures.

JR: Many independent presses are known for taking a great deal of care in the production of their books. Jaded Ibis goes even a step further with their fine art and sound editions. In the fine art editions for this, the reader has to make a decision between destroying the artwork to get to the words, or destroying the words to get to the artwork. Doesn’t this in some way contradict the “normal” edition of the book, where the text and artwork mingle? Are the fine art and “normal” editions meant to stand alone, or should they be considered equal parts of the larger artwork?

JATAJDW: Debra DiBlasi (our publisher) might be able to answer this question better than we can, at least in terms of her idea of doing these editions for all of our books. But, for us, we wanted an edition that basically indulged the obvious fault line that we had left in our work. Our collaborative method of composing a whole novel together, but sections independently, leaves the scars of our work showing. By not combining words and pictures in single sections, the separation, and hopefully tension, between these two methods of storytelling remains obvious. We wanted the fine art edition to irritate this threat that the words might overtake the pictures or the pictures might consume the words, and basically force our reader to do just that.

JR: The jacket copy describes the book as both “horror story and love story.” In my first read, it felt much the latter, perhaps because that’s the kind of story I was looking for at the moment. But in a second read, I found myself more drawn to what I guess one would call the “horror” aspects, the moments of separation. (Maybe it’s the same reason). The tension between the images and text, and the tension within the images and text themselves, seems to draw from this simultaneous coming-together and ripping-apart, emotionally. I’m curious if you find or found yourselves falling one way or another in your own emotions for the book. Does your own unified voice (as in these answers) come from equal-and-opposite forces, or parallels?

JATAJDW: Wow, Joe. I think the answer is “yes.” You described our exact experience. As we passed the story back and forth, the constant challenge was to invent (change) but by harnessing what had been given to us. The fact that this novel ended up being a story about the absolutely terrifying nature of love — the fear of loss, both of self and the person or thing that you can’t control — seems to be a likely result of the way we worked together.

An Interview with J.P. Dancing Bear

Recently I had the very good fortune to talk with J.P. Dancing Bear about his new collection Family of Marsupial Centaurs released by Iris Press. This mesmerizing collection of poems originally emerged from a desire to respond to friends on their birthdays and grew to a year-long project producing over 1400 pieces that offer a gifted poet’s integration of visual art, biographical information, and personal remembrance.

KMA Sullivan: Recently I had the very good fortune to talk with J.P. Dancing Bear about his new collection Family of Marsupial Centaurs released by Iris Press. This mesmerizing collection of poems originally emerged from a desire to respond to friends on their birthdays and grew to a year-long project producing over 1400 pieces that offer a gifted poet’s integration of visual art, biographical information, and personal remembrance. Let’s take a look at the work and a few of Bear’s thoughts on the collection.

Saint HelenaAugust 10

you hear the voice of Federico Garcia Lorca weeping: in every guitar: which are always of two minds: one searching for the strumming hands of a musician: the other desiring to sing for everyone: and does not care if it is discovered by the clumsy feet of a Galapagos turtle: which reminds you of Napoleon Bonaparte: in exile: where he took to standing on the back of a turtle: (one sailors had brought to solve the entire loneness of the Atlantic Ocean): because the turtle was so adept at ravaging the emperor’s vegetable garden: Napoleon had finally reached a compromise with something: he rode standing on the shelled back: in windswept mornings: hand in vest: reading the great philosophers: to his reptilian companion: at night: after the turtle would eclipse in heavy underbrush: then trundle over to forage the garden: the emperor would weep: having lost everything: again: even the slow moving turtle moon: with its wide O-mouth: mimicking the singing face: of a weeping guitar

—for Mark Doty

KMA Sullivan: I have to tell you that because you are the only person I know who I address as “Bear” and because you show up in my email as “Dancing,” I declare your name: Best. Name. Ever. But I feel compelled to ask — what does the J.P. stands for? If you get asked this all the time or don’t like the question feel free to ignore!

J.P. Dancing Bear: I do get asked it a lot. Jerold Pierre. Just a mouthful. I used to just go by “Dancing Bear” when I first started, but there was a singer-song writer in Santa Cruz who used that name, and another poet on the east coast who apparently did so too. And then people who didn’t know me, kept calling me “Dancing” and I just decided that adding the “J.P.” at the beginning made things easier for everyone. Although, I still get the occasional address “Dancing” . . .

Tristan and IsoldeFebruary 27

together they marry: she is always reaching out: he, with his dandelion head, is afraid of weather: in their uneven seams of shadow small animals have made a home: first mice: he has a pair of entwined trees for an advocate— roots snaking this way and that: she believes in the power of wheelbarrows: she is a strong supporter of underbrush: many birds move into her hair: there is a storm on the horizon: light breaking everywhere: and then he realizes that she is not reaching but positioning her hands to protect him from a gust of wind

—for Oliver de la Paz

KMA Sullivan: These poems are described in your introduction as at least partly ekphrastic. Could you talk about the role of visual art in the emergence of this collection? How do you think of the ekphrastic elements of the pieces as being in relation to the personal reflections about the friends whose birthdays are the springboards for these poems?

J.P. Dancing Bear: I used the artwork as the backbone. What would happen is on the occasional days where the writing workload was not too much, I would spend a few hours looking at art and would say have a feeling that it might be something I could use. I liked the various movements of surrealists best, probably because they were more malleable to the project at hand. So I had a bank of hundreds of paintings and sometimes photos. Then I would go to each friend’s Facebook wall and read their recent statuses, their hobbies, their interests, favorite music, movies, and quotes. Then I would take my notes and find a piece of art that would best go with the them. This meant my idea window for writing was something of about 20 to 30 minutes. I would generally do this in the morning, then reread in the afternoon before posting. I would say this worked about 300 days out of the year. The other 60 I would struggle harder with the work, but the idea of loosing the challenge I had given myself would finally motivate me to finish.

Floating Away at NightMay 26

you see a boat: almost too white in the night: as if the universe had forgotten to tell it to dim: its reflection ripples and drifts back to where you are: and now this feeling of needing to be on it: as it noses further into the dark: beyond the few visible white crests of waves: and it’s not for the leaving that makes you want to be onboard: not because you feel entrapped: it has nothing to do with escape or freedom: it is that brightness: slipping into the unknown: casting light where only the blackness of night is expected

—for Martin Vest

KMA Sullivan: In your introduction you mention settling on a form for this collection that you first encountered in CD Wright’s work. I am intrigued by your use of prose poem blocking while employing colons to separate thoughts. It feels as if you are imposing a type of lineation on an intentionally unlineated form. I love the tension you create with this choice. Could you talk about the ways in which this form supports the poems in your collection? What were you trying to accomplish through the form and do you feel you achieved it?

J.P. Dancing Bear: First off, the prose/colon blocking was probably about 90% of the poems; there were some straight-on free verse poems and a few gacelas, but they are not in this collection. At first, when I started the project I wrote mainly traditional prose pieces. I was satisfied completely with the end-result. Prior to this process, I wrote mainly free-verse, with an occasional venture into rhyme and meter or prose poetry. I’m not sure why I remembered two C.D. Wright poems “Song of the Gourd” and “Crescent”, it is probably because I had heard her read these poems and (because I generally consider sound above all else in my work) the form seemed a good way to build more sound into the prose work I was doing. I was instantly satisfied with the result and the style took over. When I was in the editing process, looking to submit work to journals, I rewrote a lot of the earlier prose poems into this form. I still use it to write some of my new poems.

Still Life with MandolinMarch 28

sound hole of seeds: a thumbnail moon to strum the strings of a lyric body: nourishment and lullaby: blue curtain night: greensleeves on greenleaves: ear twitch: god tonight the animals want to sup on the tender flesh of music: sprout tune: vibrate: glisten: blossom and root: fill the room with acoustic aroma: tart sweetness: seed queen: lean into lyric wondering: tendril and pluck: the musicians gather: fruit heart: they bow: they plead play in the new day

—for Ada Limón

KMA Sullivan: While the poems you created are not entirely biographical in nature, they were inspired by specific birthdays and you have mentioned using biographical information such as hobbies and interests posted on Facebook, as starting points for the different poems. Did any interpersonal issues arise as a result of this? How much license did you feel comfortable taking in the service of the poems? And did anyone respond negatively to the poem written for their birthday?

J.P. Dancing Bear: In the total 1408 poems I wrote, there were two people who responded by saying that they didn’t think the poem accurately captured them. The feeling I felt is very much the same as when you give a gift to someone that’s “wrong.” It’s a little more than embarrassing and I guess I should count my good fortunes that it didn’t happen more than that. The main reaction that I got from the poems were a lot of people were really thrilled by their poem and I still get messages from people thanking me for the gift. I think this has brought me closer to a lot of the recipients, as mutual fans, contemporaries and friends.

Nautical Still LifeAugust 11

you are watching on the breezeless deck: as though you have stumbled upon a still life: a square is mocking another square: because it has found a life boat: canvas bunches to make the outline of a face: you say quit casting shadows: but only more lines fall: you call out: the aura of oars: but they stand straight-faced: not a hint of laughing: even the flags are twisting: they dream of becoming boomerangs: almost free enough to soar away: you test the rigging: yes—taunt enough: the oars are jealous: of the lifeboat’s rudder: everything is so anxious in its aspiration: you can see the sun starting to sink: red skies—those damn lucky sailors

—for Dana Guthrie Martin

KMA Sullivan: Could you take us through the process you employed in taking a set of over 1408 poems and cutting that down to 82 in the finished book? This seems a mind-bending task. Did some of your thoughts about the collection shift during the editing process?

J.P. Dancing Bear: I didn’t actually go back and begin editing the originals until I was half way through the project. At that point I started pulling the poems that I felt best about and began the normal editing process of evaluating word choices and phrasing. Then some of the decision process was made by poems being published and some of the responses I received from those published poems. When I was contacted by the publisher, I had a group of about 160 poems that had gone through the editing process at least once. I then read through them and picked the ones that I thought went best together. I’m still going through the birthday poems and editing them now, and more have been published since then. I now have a second manuscript of birthday poems put together and ready.

By DesignMay 17

someone is always crafting something: an animal built for travel: retractable wings: rudder: engine room: and wheels: here you say love is the possibility of shapes: down a hallway and you are following ribboning lines: and you think about language: being fluid: flowing: here you say a language without love would surely die: someone is stitching fabric to a couch: one they have imagined: framed: cut from wood: here you say love is building a place where your friends can relax—stay a while—and talk

—for Patty Paine

KMA Sullivan: The strict parameters you set for yourself regarding poem generation within this project are striking. Has that working process influenced your current creative process?

J.P. Dancing Bear: YES! Since the birthday poems project ended, I started a Facebook group that has a weekly ekphrastic challenge. And so once a week, at least, I usually can sit down and write a poem to a painting. The birthday poem project also made me realize that writer’s block is a mental block writers imposes upon themselves for whatever reasons.

SymbioticSeptember 30

the woodpeckers are in love with your new look: ruff of a burl: ball dress of wood: you prefer peacocks: the eyes of Argus: look out: o look out: for the predators of burrowing birds: nesting near hoops: in knotholes and grains: they flap at all intruders: you feel safe in their graces: this family of beaks and quills: you watch after the fledglings: when the parents forage: they nuzzle in tight: under the eaves of your collar: sometimes the adults bring you a bouquet of dandelions: pulled out by the roots: you’ve developed a common language of life: you help preen their speckled bodies: they stencil your gown: in a pattern: percussing a code: a code: a code: of love

—for Julianna Baggott

KMA Sullivan: Can you tell us something about what you are working on now?

J.P. Dancing Bear: I just finished a year long project of 52 love poems based on a lot of surrealist artwork. And I’m still working in the Facebook Ekphrastic group, and out of that group I’ve realized a sub-project of “days” which started last year when I wrote a poem titled “Labor Day” and one titled “Father’s Day”. I’ve written four more since then and now I’ve realized what it is, I’ll finish it out. And I have a second manuscript of birthday poems now compiled.

KMA Sullivan: Thank you so much to J.P. Dancing Bear for offering his time and his poetry. Let’s finish with one more from Family of Marsupial Centaurs.

WritingNovember 19

today you sit down to write in long hand: you dress the part: in garb from another century: quill pen and inkwell: but this is only for mood and ambiance: you work through the process slowly: you build stanzas: intricate metrics and geometry: tiered lines: words with angles: each as valid as the other: spheres orbiting refrains: edges are created: sections are not X’ed out: so much as an exit to begin new ideas: you embody the poem: taking on its features and angles: or it becomes you: bringing to light those curves and corners you had not realized are there

—for David Yezzi

Saying Just the Right Thing At Just the Right Time: A Round Table Discussion with Billy Longino, Alex Taylor, and Jenny Hanning

What these three writers have in common is a mastery of setting. They deliver their stories with the confidence only a native character born inside their storied worlds could give; they have the ability to say just the right thing at just the right time.

Weeks after weaving through the overwhelming crowds of AWP, I finally got around to tackling the large pile of books I had acquired. Black Warrior Review (BWR), issue 38.2, was at the top, and I found it to be chock full of amazing work. So, instead of concentrating on one voice to represent the whole journal, I found three unique writers who came up with three individual stories, as distinct in setting from one another as war-torn Mexico is from the backwoods of the southern United States — different, but interestingly similar as well.

What these three writers have in common is a mastery of setting. They deliver their stories with the confidence only a native character born inside their storied worlds could give; they have the ability to say just the right thing at just the right time.

In “The Burial,” by Billy Longino, we meet an albañil whose son has just been killed, and who’s been given the mission of burying his son alongside his mother’s family, in a cemetery many miles away, in a village that was “abandoned when the silver mines closed and the maquiladoras opened in the city,” a dangerous city, a city so dangerous the priest refuses to travel to them and, instead, gives last rites over the telephone line. “The Burial” is as much about interring the child as it is about the place the child is being buried — and it is the author’s language that makes both the character and the place come alive.

Alex Taylor’s story, “Spare Parts,” is likewise connected to its scenery through language. He uses a language that is both of the junkyard and . . . other. Taylor intermixes junkyard jargon — “give him a dose of Keystone and then take him to the dirt” — and intelligent descriptions that are, perhaps, smarter than the narrator himself: “What he wants is a spell to get a peek at your wang. Lute is enamored with wangs. He peruses them. The reason for this is Lute’s own pecker is a deformed oddity pinched between two of his brown fingers, thin as a cowboy-rolled smoke, the head knotty and swollen.” The narrator relies on the junkyard, is a participant in that world, and yet, he gives us an experience of that place that makes the junkyard universally understood.

Another premise all three of these stories utilize is the source of silence, of Truth, of something — and this something torments the narrators.

Jenny Hanning’s “A Family Price,” describes this silent something as a misunderstanding in our brain. She calls it “The Blink Effect”: “Of the human senses, our most powerful is sight. The human eye sees faster than the human brain can process. . . . An average blink is two hundred milliseconds, eight hundred short of a full second, maybe the curl of the tongue in preparation of saying one Mississippi. A beat behind, the brain struggles, stutters, fills in the blanks base on familiarity or fears.” Miscomprehension occurs in Hanning’s story in the same way it does in Taylor’s and Longino’s: both literally and emblematically. Each story describes itself in a physical setting, staged gorgeously, and with a tangible climax, but each story also alludes to a silent something with which the main characters struggle.

Here’s what the authors had to say:

The Lit Pub: So you’ve all been published in the same issue of BWR. Have you read each other’s stories? What do you think of the issue, of BWR in general, and how did you go about choosing to submit your stories there?

Alex: I’ve read Mr. Longino’s story but have yet to set down with Ms. Henning’s. I was quite impressed with Mr. Longino’s tale and I am honored to be in a journal with as long and prestigious a history as the Black Warrior Review.

Billy: Alex’s language was fascinating to read, it’s very acrobatic. And I thought Jenny’s interjection of “The Blink Effect” was enviable. The reason I submitted to Black Warrior Review was just because they have a consistent, unique aesthetic, visually and in the work they select, that I greatly admire, which Alex and Jenny’s work fit very well.

Jenny: I have also read—and enjoyed—Billy’s and Alex’s stories. When I submit, it’s to journals that I like to read, so it was a real pleasure to be included in BWR alongside so much interesting work.

Literary journals can be hard to pin down at times; they can have hard-to-describe aesthetics — even after reading a few issues. However, after reading the three of you, I think I have a better sense of what the BWR editors (of this issue at least) were looking for. You are all three completely unique writers, and I think that is the very attribute that makes your writing attractive. You create unique worlds, and it’s only in these worlds, with their explicit languages, that the story can exist.

TLP: Can you comment specifically on the way your language (tone, word choice, etc.) connects to setting and character in your stories?

Jenny: I think that place and identity are inseparable. Where a person is from influences who they are in a million nuanced ways, some obvious and others not, but all equally defining. So, to me, character is an extension of setting—or a product of it?—and vice versa. It’s a goal, though maybe not one I succeed at, to represent a place, and through that, the people living in it, accurately. Life changing events happen without markedly changing daily life.

Billy: I agree. In my work at least, I think language is inseparable from setting. The way language presents the setting must come naturally out of the setting itself, otherwise it feels disjointed—unless, of course, that’s the point. But in “The Burial,” the bleakness of the landscape is totally consumed by the language and presented to the reader, or I hope it is anyway.

TLP: The language of your landscape, Billy, does exactly what (I think) Jenny is talking about when she says the representation of a place brings out the people of that place. The way you describe the open dessert, with the whipping sand and wind, makes me think of the hard work a man must commit himself to for the journey across that space. Your main character is exactly that man — the albañil, the bricklayer. What were your thoughts behind choosing that name?

Billy: I don’t really remember my initial thoughts. I think I might of wanted a character whose job was something old, almost Biblical, but also something day laborers still do. As for being nameless, people like the albañil are always nameless in our daily lives.

TLP: The Burial reminds me of the language in Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory, and maybe a little of Silence by Shusaku Endo, but unlike your characters, both these writer’s main characters are foreigners struggling with a language barrier. How do you see the intermixing of Spanish and English working in your story?

Billy: I don’t believe that any actual barrier exists between the United States and Mexico beyond the metaphorical, and I think, at least, the languages represent the illusory nature of the border in their spillover. Being white and a native English speaker in the neighborhood and town I grew up in, I was a minority. To me, Spanish has always been symbiotic with English. They seemed inseparable. It’s just what I heard every day of my life. So, for me, the intermixing of the two languages represents the complex cultural connections between the U.S. and Mexico that are largely ignored by certain political elements in this country — the same politicians building that fence-simulacrum across empty desert. Language merging is a force of intercultural systems, to which no borders exist. Sorry, I’m a little obsessed with this.

TLP: Interesting. So the Spanish wasn’t so much an insertion into your work, rather, the mixture of the two languages was native to your landscape?

Billy: Right, to think of the Spanish as being inserted is to think of it as something that doesn’t belong, when in actuality the English is really what doesn’t belong in this story, as the only one who speaks in English is the man in the church, unless you count the narrator too. But to answer the question, Spanish shouldn’t be something seen as alien in our culture, or our literature, or something inserted, which implies a sort of invasion, but something that is an intrinsic part of the daily lives of many of us in this society. Spanish and Spanish speaking people shouldn’t be seen as living on the margins of American narratives.

TLP: Alex, “Spare Parts” has a language all its own as well.

Alex: I write about people whose common everyday idiom is infused with poetry. However, it’s the poetry that has either been neglected or maligned as being evidence of ignorance. I am influenced by Zora Neale Hurston, who saw the value of the common speech patterns used by the poor and uneducated. Further, my characters often employ language that is inseparable from the rhythms of the natural world. They are noticers. They observe the metaphors inherent in the land and speak accordingly.

TLP: That’s a gorgeous way to see language. Can you recommend a work by Hurston we should all read?

Alex: Their Eyes Were Watching God and Mules and Men are the best examples of Ms. Hurston’s flair for the colloquial and the way she makes it transcend local geography.

TLP: I mentioned before that your narrator seems both of the junkyard, and aware of the world outside it. He seems uncomfortable with the situation at the junkyard, and at the same time he seems familiar with the whole scene. Can you explain his inner conflict?

Alex: Well, he’s trying to be absolved of his past sins by returning to the junkyard that’s operated by a man he tormented as a boy. I think a lot of my characters tend to wrestle with guilt. I don’t view it as an entirely unhealthy emotion, guilt. Rather, it seems to indicate a richness of soul.

All good characters have complexities.

TLP: Jenny, let’s talk about this Blink Effect you got going on. Two pages into “A Family Price,” you pause to give us a definition of it before continuing on. How do you see this specific explanation working in the story?

Jenny: I think that the pause and explanation needed to be there for the story to track. And, it’s interesting, to me at least, that we say, “Seeing is believing,” when we can’t trust our own eyes, or, on a larger level, our initial perceptions. It’s disorienting when you misinterpret something, respond to the misinterpretation, then have it corrected, and have to re-sort your reactions. It reminds me of how memory operates.

TLP: Some people might say memory has a way of attaching itself to the landscape as well, just as much as language might. What do you think?

Jenny: I agree, absolutely. A place can hold an experience, and when it’s revisited, what happened there can feel just as fresh or raw, even years later. That may be a cliché? — but it’s true! Sensory details, I think, play a large part in a landscape’s ability to recall events. All the unique qualities of a place contribute to how it’s remembered and become triggers for memory.

TLP: That’s definitely the way in which I see landscape, by how I’ve seen it before, what I was doing then.

Alex: The place I come from is burdened with memory. A friend of mine was riding over his farm one day and spied two bobcats sitting on a log at the edge of a field. A rare and exciting scene, as bobcats are notoriously elusive. As he was recounting the moment to me, he said, ‘If I hadn’t spent all my life looking at that piece of ground I wouldn’t have noticed those two cats.’ This is indicative of the attention my people pay to their surroundings. They stare long and hard at things as seemingly mundane as fallen oak trees, and they learn to remember the lay of their land so that any change is noticed immediately. I call it a burden, this looking and this remembering, but that may be inaccurate, in so much as ‘burden’ indicates hardship and toil. Perhaps what I mean is my people are wardens of memory. They are tenants of recollection, working on shares for the place that has held them close and kept them safe.

Perhaps our memories trap a place in time as much as they enhance the landscape.

TLP: The pause you give, Jenny, to explain “The Blink Effect” isn’t the only time we hear that tone of voice. We also here about the way deer pause in headlights, and how we mistakenly call the smell of gunpowder cordite. These explanations seem to be a function of the narrator. Why did you decide to narrate this story from a bystander’s perspective?

Jenny: I hadn’t thought of it like that, but I can see what you’re saying. In my mind, those asides or pauses are the same narrator as the “I” in the story, trying to give context for his experience, rather than a true bystander perspective. We describe things through comparison to clarify them, but how do you describe something that defies comparison?

You definitely wouldn’t have been able to work with that idea of the indescribable if you were to put it in the brother’s perspective. It’s interesting how the same story can be told so differently through point of view. I think it’s that silence — that miscomprehension — at the end of your story that really sticks with you.

TLP: Billy, there’s a certain stages-to-silence that happens in your story as well. In the beginning, the albañil tells his son about God. Then, once the son is killed, the albañil refuses to talk about God. Lastly, in the end, the man in the church puts a finger over the albañil’s lips and prevents him from defending God. What do these stages of silence represent?

Billy: I’m not sure I can begin to comprehend what silence means in Mexico these days. Silence is sanctuary; silence keeps you alive. But silence terrifies us; we think it’s unnerving or whatever. There is a paradox there that is sad and beautiful. Then there is the act of being silenced and what that means. The albañil couldn’t even tell God what he had witnessed. The son is silent through the whole story because he is dead. And, of course, God is silent, too. I hadn’t really thought of this before. It’s interesting.

TLP: Maybe that’s the point of stories like the three of yours, they leave you something to ponder in the silence after reading.

Billy: Thinking-in-silence is something everyone needs and do not seem to get enough of in the information age. That’s the great thing about short stories, as opposed to TV shows, you’re not immediately bombarded with more stimuli as soon as it ends, except what’s coming from your subconscious. Thankfully there’s no algorithm to implant an advertisement for low cost tombstones after my story in BWR.

Thankfully! (yet).

TLP: Thank you all so much for sharing your thoughts with us! Any last comments or reading recommendations?

Billy: Thanks.