Metamorphic Imaginaries: A Conversation Between H. L. Hix and Dante Di Stefano

Reading The Gospel was a profoundly moving and unsettling experience for me, mainly I think, because of the way that you redress the deficits caused by translation inertia and gender tilt. You speak about this at length in your introduction to the book, but I was wondering, if, for the purposes of this conversation, you could discuss those aspects of the text?

DD: In the introduction to The Gospel, you note: “This book is not ‘creative writing’ or ‘imaginative literature’ in the sense that applies to those works [books about the life of Jesus by Saramago and Coetzee]. I did not ‘make up’ anything here. I selected, arranged, and translated all the material, but I invented none of it: everything in The Gospel derives from ancient sources, nothing originates with me.” It strikes me that much of your work (and especially your more recent poetry collections such as American Anger and Rain Inscription or even books like Demonstrategy and Lines of Inquiry) blurs the boundaries between poetry, prose, criticism, philosophy, translation and so on; sometimes when I read one of your books, I think perhaps there are no boundaries between these modalities of engagement. You always bring me back to Benjamin: “all great literature either dissolves a genre or invents one.” Could you talk a bit about The Gospel, and your body of work, with some of these thoughts in mind?

HH: Thank you for this generous question, itself a robust modality of engagement that sees a continuity between The Gospel and my previous books.

Because the fact is so easy to forget, it’s worth occasionally reminding ourselves that genres are made up. Genres are not what philosophers call “natural kinds,” distinctions that exist in the real world independently of us, and that our categories then correspond to (or fail to correspond to). Instead, our categorizing creates and sustains genres, and they never “pull away” into an existence independent of our conceptualizing. They’re invented, not discovered, and they’re not very tidy: a novel isn’t distinguished from a short story by the same principle that distinguishes a novel from a memoir. Our genres don’t “cut literature at the joints.”

Which makes them susceptible to questioning. I would string the pearl you offer from Walter Benjamin with this pearl from Audre Lorde: “For those of us who write, it is necessary to scrutinize not only the truth of what we speak, but the truth of that language by which we speak it.” And this from Amartya Sen: “We can not only assess our decisions, given our objectives and values; we can also scrutinize the critical sustainability of these objectives and values themselves.” All three, like your question itself, point toward an urge that drives all my writing: not merely to renegotiate one particular agreement or another between us, but to reveal, and thus to make available for evaluation and revision, the “metastructure of consent” (Lauren Berlant’s term) that has been governing all our agreements.

So you’re right to pose the question of genre to The Gospel. To read for the gospel exclusively by haggling over what Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John wrote is to grant the metastructure of consent that says those four texts and only those four texts contain the gospel. But that metastructure of consent is constructed, not observed. It doesn’t describe a quality inherent in those four texts; it imposes a rule on my behavior, setting limits to what I should read and how I should read it. The Gospel is a way of asking what that rule hides from me, a way of asking what I can see if I don’t follow the rule, that I can’t see when I do follow the rule.

The fact that several poems in the Ill Angels’ first section are addressed to your students leads me to ask you a version of the same question. If you talk to students all day in class, in that modality of engagement, how important is it to talk to them also in another modality of engagement, in poems? And how important is it to you to address a particular person or group in a poem?

DD: It’s both of utmost importance and of no importance at all. In some sense, any addressee is merely a trope, part of the poem’s furniture and frame. Sometimes when I reread a poem I’ve written I feel like I’m speaking to myself in a small empty room and sometimes I feel like I’m speaking to all the round earth’s imagined corners.

I do speak to students all day long in my job as a schoolteacher, and sometimes those conversations are poems, sometimes those conversations die into poems, sometimes poems die into those conversations, but most of my students will never read the poems I write. Still, addressing my students in a poem shows that I care for them deeply—it’s a form of prayer for their wellbeing and future success. Deep attention is the highest form of love; embodying and engendering deep attention is the work of poetry and the work of teaching.

The greatest two words in all of literature are the epigraph to E. M. Forster’s Howard’s End: “only connect.”

After the birth of my daughter, it became very important to me that in the future she might read my poems and understand something about her parents that might otherwise remain hidden to her. In a very real sense, my wife and my daughter are the ones I am always speaking to in any poem I write.

Who do you see as the ideal audience for The Gospel? Who is this book for?

HH: The glib answers to this question—It’s for everyone! and I write for myself—do point toward something that I think is not at all glib. I myself experience an awe before the world and a wonder at experience that could be called “religious” because they convey a sense that in what meets the eye there is more than meets the eye. But I haven’t found (yet!) an institutional form or a heroic figure or a codified set of beliefs adequate to that awe and wonder. I wrote The Gospel for myself, then, in that the awe and wonder I feel invite continuing exploration in preference to settling on (or settling into) a received framework. And The Gospel is for everyone in that of course I’m not the only person who feels awe and wonder, or the only person intent on continuing to look toward what I can’t yet claim to be looking at.

While we’re thinking about who is speaking to whom, the first poem in Ill Angels, “Reading Dostoyevsky at Seventeen,” ends “This is the part where I take your hand in / my hand and I tell you we are burning.” If angels are messengers, as the etymology of the word suggests, does the “I tell you” in that last line alert the reader that the speaker is one of those ill angels in the book’s title?

DD: I hadn’t thought of that possibility, but I think it’s a smart reading of those lines. The ill angels from the title are the ill angels from Poe’s “Dream-Land,” which begins: “By a route obscure and lonely, / Haunted by ill angels only.” To me, “Dream-Land” is a “fantasia of the unconscious” (to borrow a phrase from D. H. Lawrence); it’s a poem about journeying deeply into the self in order to turn outward more ardently. These ill angels are the legion woes that amass in the four chambers of our hearts as we go through this life; they are our dead, our regrets, our wounds, our arnica and eyebright, our hopes, our dear ones—they hold out the possibility of seeing ourselves the way a stranger does, unfolding in moments. In some sense, all the personae speaking through these poems, and all those spoken to, are these ill angels.

On an entirely different tack, I was reading in The Atlantic about Thomas Jefferson’s redacted New Testament, which he called The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth. Jefferson’s version expunged all the supernatural elements from the gospel. Your version adds miracle upon miracle from the ancient source material. We have, for instance, the baby Jesus taming dragons on the flight into Egypt, a trip during which he collapses distance and time. I was delighted by these stories, especially the ones from Jesus’ childhood. Has your conception of Jesus (as character, as metaphor) changed during your selection, arrangement, and translation of this material? What can we learn from the Hixian Jesus? How does this Jesus speak to our era?

HH: Jefferson was very concerned with the operation of things. How did things happen? How do thing happen? How will things happen? That concern invites historical and scientific accounts, which are especially good at answering those questions. An answer to how things happened should leave out miracles. There are no miracles in the domain of cause and effect.

I value historical and scientific accounts, and I am interested in how things happen, but I am even more interested in what things mean. I share Jefferson’s sense that the answers to those questions should be coordinated as far as possible, but I don’t share his strategy of coordinating them by only asking how things happen. I share Jefferson’s assessment that how things happen is an important concern; I choose not to follow him in making it so exclusive a concern.

A person who wants to know how things happened (what actually took place in the Middle East 2,000 years ago?) or how things happen (how do political institutions and religious institutions shape one another?) should get rid of supernatural elements in the narratives. A person who wants to understand what things mean might decide to attend to those supernatural elements, with the possibility in mind that they have more to do with significance than with cause and effect. Historical narratives are really good at answering how things happened, and scientific narratives are really good at answering how things happen. Literary narratives are really good at answering (or, I would say, at addressing) what things mean.

I don’t for a second think that a real goddess named Athena really appeared in the guise of Deiphobus to trick Hector into squaring off with Achilles, but I don’t take that or any of the other supernatural elements out of The Iliad, because I’m not reading The Iliad to find out how things happened; I’m reading it to find out what things mean. For me, it’s the same with reading a Gospel. I don’t believe, as an historical record of actual events that really occurred between physical entities, that baby Jesus tamed dragons, any more than I believe, in that way, that Beowulf slew a fen-dwelling monster named Grendel. I don’t think the writer who recounted the baby-Jesus-taming-dragons story in the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew is offering me, and I’m not reading that particular story for, an historical record of actual events that really occurred between physical entities. I do think the writer of that story is signaling me that Jesus is exceptionally attuned to what today we might call the more-than-human world. I’m not any more worried about whether baby Jesus really tamed actual dragons than I am whether Gregor Samsa really turned into an actual giant beetle. So, I’m happy to stock The Gospel with lots of miracle stories: bring ’em on!

Miracle stories or not, literature remains connected to real events and real people. We’re engaged in this conversation as a deeply contentious election looms, and I’ve written one book called American Anger and another called Counterclaims. I just want to hear anything and everything you have to say in relation to your lines “Here in America, trauma and rage / dovetail, become birthright, counterclaim us.”

DD: The poem that those lines come from (“National Anthem with Elegy and Talon”) is about the intergenerational impacts of mental illness and domestic abuse, as much as it is about notions of national belonging and the experience of living in the United States in the early twenty-first century.

As many writers have noted, due to systemic racism, widespread misogyny, income inequality, a variety of broken social institutions (the public-school system, for example), and so on, daily life in America has been traumatic for many people for a long time. Fear, pain, and hopelessness accrue into rage and/or apathy (American Anger charts some of these tributaries). Any degree of safety and comfort we might experience as American citizens is underwritten by violence at home and abroad; this violence makes demands upon us all. No wonder that, in W. C. Williams famous formulation, the pure products of America go crazy, driven by a “numbed terror / under some hedge of choke-cherry / or viburnum, / which they cannot express—.” The Trump era has rendered much of this suffering, anguish, and violence far more legible to far more Americans than ever before.

In the beginning of Counterclaims, you note: “Poetry offers instead a field in which transformation becomes intelligible: a metamorphic imaginary, a landscape of renewal. The new self enters the world first in and as imagination. The new self is made by making.” Huge swaths of American life run counter to a metamorphic imaginary. I feel my self being constantly unmade, as a consumer, as a citizen, as a man; the feeling of that unmaking might be where a commitment to poetry begins.

Thinking of this kind of unmaking calls to mind the claims that the canonical gospels make on western readers. Reading The Gospel was a profoundly moving and unsettling experience for me, mainly I think, because of the way that you redress the deficits caused by translation inertia and gender tilt. You speak about this at length in your introduction to the book, but I was wondering, if, for the purposes of this conversation, you could discuss those aspects of the text?

HH: Thank you for drawing attention to these two concerns, which were very important motivations for my undertaking The Gospel. The concern I call “translation inertia” is that a great many word choices in existing English translations of the canonical Gospels have become fixed by convention, even though the English language is continually changing (as are human societies in which English is spoken). Those word choices have become static, even though the relationship between the Greek word being translated and the English word used to translate it is dynamic.

I give a few examples in the introduction, but the list could be expanded. To follow up on one example that is only mentioned in the introduction, every previous English translation I’m aware of translates the Greek word christos as Christ, an obvious enough choice since the English word is a transliteration of the Greek word. But that “obvious” translation distorts something very important. The Greek word does not only refer, it also describes. In this it resembles, for instance, the English word president. “The President” refers to an office or to the person who holds that office, but it also describes the office or person as one who presides. The noun president relates to the verb preside, and the noun christos relates to the verb chrio, to rub a body with oil or dye or ointment. The English word “Christ,” though, doesn’t have a correlative verb form; it only refers, without describing. To capture that missing descriptive element, in The Gospel I translate christos as “salve,” which does function as both noun and verb: I can salve a wound or apply a salve to a wound. So “salve” describes as it refers, the way the Greek christos does, but the English “Christ” doesn’t.

The impulse to contest gender tilt is slightly different. Insofar as The Gospel is at all successful in resisting translation inertia, it is to that extent closer to, truer to, the original language of the sources; insofar as The Gospel succeeds in resisting gender tilt, to that extent it compensates for a limitation of both source and target language.

We recognize a problem with, say, Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling, a limitation in its depicting God as a thickly-muscled, light-skinned, heavily-bearded male, and we recognize a similar problem in referring to God as a male, and assigning God masculine roles such as father. The Gospel is an experiment in not doing so. I didn’t figure out a way to get The Gospel to pass the Bechdel Test, quite, but I hope its approach to degendering references to God and Jesus at least helps it not flout the Bechdel Test!

On a lighter note, I nominate you for President of National Poetry Month, and for “emotion recollected in tranquility” I substitute “a world less rickety, ricocheted with uncompromised shining.”

DD: Then, I’d recommend replacing “spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings” with your lines “…it is our work to send you careening / from consciousness to consciousness like tumbling down a hill.”

One of the stories from early in The Gospel stayed with me:

Walking once with xer mother across the city square, Jesus saw a teacher teaching some children. Twelve sparrows flurried down from the wall, bickering, and tumbled into the teacher’s lap. Seeing this, Jesus laughed. The teacher, noticing xer laugh, was filled with anger, and said, What’s so funny? Jesus replied, Listen, a widow is on her way here carrying what little wheat she can afford, but when she gets here she’ll stumble and spill the wheat. These sparrows are fighting over how many grains each will get. Jesus didn’t leave until what xe’d predicted had occurred. The teacher, seeing Jesus’ words become accomplished deeds, wanted to have xer run out of town, along with xer mother.

There’s so much to note and wonder about in this passage. We glimpse Jesus’ sense of humor, but its architecture remains a mystery. We see a link between Jesus’ clairvoyance and the clairvoyance of the sparrows. And I am left with many questions. Why is he laughing at the sparrows? Why does Jesus wait to see his prediction come true? Why doesn’t he help the widow? And so on. I will think of this anecdote every time I think of Jesus; it has subtly altered my perception of the metaphysics of the world presented in the Christian scriptures. What moments from The Gospel stay with you? What moments have altered your perception of the world presented in the Christian scriptures? And, out of personal curiosity, what’s your take on the passage I quoted?

HH: There are a lot of reasons to love that story, I’m sure. A couple of resonances are particularly strong for me.

One is by connection with Kierkegaard’s take, in Fear and Trembling, on the Abraham and Isaac story. Against the reassuring moralistic reading of the story that highlights God’s substitution of the ram for Isaac, and takes the point of the story to be something like Never fear: no matter how bad things look, God will rescue you, Kierkegaard foregrounds God’s command and Abraham’s obedience to it. The takeaway Kierkegaard registers is more like God is not bound by your judgments of value; God does not have to act the way you think God should. I hear something similar in this story, a reminder not to get too lazy or too cocky in thinking that Jesus just performs my vision of what’s right. Maybe Jesus is a rounder character than that, and maybe my vision of what’s right isn’t finished and perfect yet, but needs continuing adjustment and refinement.

Another resonance for me is with contemporary events. In the story, the teacher, confronted with truth, does not respond with self-correction and grateful embrace of truth: he responds with rage, and an impulse toward violence against truth and the bearer of truth. The teacher in the story seems to me to share a temperament with Trumpist America, the rage and violence being acted out against the truth of racial injustice, and against the bearers of that truth.

We live in an era where “facts” and “truth” are being constantly called into question in public discourse. For a collection that feels securely “grounded” in “real life,” Ill Angels also seems ready without warning to venture into surreal or dream worlds (“Because all the animals are kings and queens, / I wait for the rain to paint me”). How do those worlds connect for you? How do you want them to connect in the poems?

DD: William Blake’s visionary phenomenology inspires me. In one of his letters, Blake famously wrote: “The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing which stands in the way… As a man is, so he sees.” Most of the times, I see the green things in the way, but I want the tears of joy. I want to learn to bear the beams of love. I want “To see a World in a Grain of Sand / And a Heaven in a Wild Flower.” Poetry trains me in this direction: in a poem, I hold open the palm of my hand and hope for infinity with its skylarks and lambs and caterpillars and lions and oxen and owls and, even, its poisons…

I think Blake would have loved your translation of the Sermon on the Mount as much as I do; this sermon forms the heart of any version of Jesus’ teaching. You translate, for example, the famous “Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth” as “Graceful, the unassuming: they will inherit the whole earth.” Could you discuss your translation choices for the beatitudes? Also, how does the additional material you included change the sermon itself?

HH: I’ve been dissatisfied for a long time with “blessed” as the translation of the Greek word makárioi in the beatitudes. It has been the obligatory translation ever since the King James: everyone translates it that way. But there’s something deeply misleading in that choice. Blessing comes to me from outside. I’m not blessed in myself, but blessed by something. Which allows for blessing to be transactional, part of a system of reward and punishment. It sets up “for” as the translation of the Greek hóti, to suggest that the blessedness derives from what comes after the hóti: the meek are blessed because they will inherit the earth, their blessedness consists in their inheritance.

But that’s not the flavor of the Greek at all. Makárioi is the collateral form of mákar, the primary meaning of which is the disposition, the well-being, of the gods, by contrast with that of humans. Its other uses are extensions of that primary meaning. Mákar is a godlikeness. It inheres in me, arises from within rather than being bestowed from without. It’s not a change of state imposed on me by something other than myself, it’s who I am. In the usual English translation it’s a transaction: if you are meek then you will be rewarded for that meekness by inheriting the earth, by which reward you will become blessed. But in the Greek the quality of being mákar is attended by inheritance of the earth. In the usual English translation, the value of being meek is utilitarian, teleological: it’s good to be meek because of the good results it brings. The value is in inheriting the earth. The usual English translation makes being meek a sound investment, and makes the rationale that runs through the beatitudes “rational self-interest,” the profit motive. In the Greek, though, the value of being meek is intrinsic, deontological.

I’ve tried other approaches. In a previous version of the beatitudes, the one in the sequence called “Synopsis” (in Legible Heavens and then First Fire, Then Birds), I used “replete” for makárioi. In The Gospel, I chose “graceful.” Maybe better, maybe not, but what I was aiming for was restoring the implications of the original that makárioi inheres in the person and has value in itself.

The beatitudes work by repetition. The intense repetition in your “Solo” feels like the intense repetition in A Love Supreme, which “Solo” cites (and there are numerous other jazz/music references throughout the book). But “I am beyond professing music now,” one of your speakers says in a later poem. How do experiences of music and other art forms relate to your work as a poet?

DD: Music and the visual arts nourish me as much as poetry; both artforms suggest a range of possibilities for what a poem can be (picture a poem as expansive and effusive as a Mingus composition, a poem as repetitive and minimalist as a Philip Glass piano etude, a poem as gesturally complex as a Jackson Pollock canvas from the drip period, a poem as Baroque and phenomenologically complex as Velázquez’s Las Meninas).

The work ethic of Jazz musicians inspires me. The romantic images of Sonny Rollins woodshedding to the wind on the Williamsburg Bridge and Charlie Parker playing for the cows in a pasture belie a daily and total commitment to their art that is common to all of the artists I most admire.

The goal for me is to be always engaged in poetry, to dwell in poems the way I might dwell in the red ochers and umbers of a Caravaggio or the blazing hues of a Basquiat.

Another moment in The Gospel that moved me occurs after Jesus goes to the Mount of Olives and then returns to the temple to teach; the scribes and pharisees bring before Jesus a woman caught in the act of adultery for whom Mosaic Law mandates death by stoning. The scribes and pharisees ask Jesus what they should do with this woman. Jesus’ lengthy response turns into a Whitmanesque (and Blakean) view of divinity and humanity—the godhead in the biosphere: “This is wholeness of life, to know oneself in and of the whole.” I am thinking of the section that runs from “I am the first and the last” to “I am xe who cries out and xe who hears the cry” (104-106). What do you make of Jesus’ discourse at this moment?

HH: I share your attraction to that passage, which comes from an amazing text called Thunder, Perfect Mind, part of the Nag Hammadi find, that gives a first-person address by a female deity. It does have that quality you point out, that is familiar to us from Whitman and Blake. I think what I am drawn to is the contrast with our more usual epistemology. That dominant epistemology (whose champions would include Descartes) posits that everything is in principle explicable to the human mind, everything is subject to human reason. But what if that’s just not true? What if nothing is subject to human reason? Who am I then? How do I stand in relation to the world? This passage seems to me to take those questions seriously.

That passage doesn’t fulfill the usual preconception, the norm that has come to be associated with gospel writing. “Brief Instructions for Drawing…” is not a “My love is like a red, red rose”-type love poem. (Nor are the love poems that follow it.) What impels the veering away from that “normal” approach?

DD: Because of the misogyny embedded in the courtly love poem, the English and American poetic tradition has always invited a subversion of the power and clichés associated with erotic and romantic themes; Shakespeare’s sonnets are, of course, a huge pivot in the tradition.

In my own life, I’ve found that nothing has been more productive and more challenging than the love I share with my wife. Being in love is a choice, full of daily unromantic tasks and realities. Being in love is a political and moral act; for me, writing about love should be too. Being in love is both the most transformative and the most mundane experience a human being can undergo. To return a phrase of yours I quoted earlier, love offers us “a landscape of renewal” like the field offered by a poem. In a poem and in love, a new self is made by making.

HH: A related question arises for me in relation to your “Epithalamion with References to Philip K. Dick, Paul Klee, and Gene Roddenberry.” Your titles seem to equal parts orientation for the reader and disorientation. What is the relation for you between a poem and its title? What do titles do for you?

DD: Sometimes a title is like a light switch in a darkened room; it’s the first place you go to illuminate a text. Sometimes it’s a dimmer switch. Sometimes it’s a circuit breaker. Sometimes it’s a live wire, exposed and sparking. Sometimes it’s not wired into the structure of the poem at all. Sometimes it’s a satellite, a dose, an antidote.

My titles tend to be expository, subversive, allusive, and metapoetic. I’d like any title to orient and disorient simultaneously.

The Gospel constantly reoriented me as I read it. The passage I mentioned (about the discussion between Jesus and the scribes and pharisees) also recalled the ways in which The Gospel nuances (challenges, confirms, reorients) my understanding of gender and misogyny in the Christian scriptures. Is The Gospel a feminist text? Did your synthesis of the source material reorient your understanding of gender and misogyny in the Christian scriptures?

HH: Readers will have the final say on whether The Gospel is a feminist text, but my intention was to compose it as a feminist text, and my hope is that it may prove to be so. I take this as a criterion: if there is gospel—good news—that any given Gospel (Matthew’s or Thomas’s or mine) tries to give an account of, that good news is equally available to all persons. If it’s good news for white persons but not for persons of color, then it’s not good news at all. If it’s good news for men but not for women, then it’s not good news at all. I don’t claim success, but I did attempt to incline my Gospel in the direction of that feature of the gospel. It’s the impulse behind the gender-neutral pronouns for God and Jesus, and the coinages such as fother and xon.

An impulse behind a work is susceptible to personification as a muse or spirit. Asked who has been appointed in heaven as presiding spirits over this book, I would guess John Coltrane and Gerard Manley Hopkins. Who have you requested as presiding spirits?

DD: Those are the two greatest saints in my litany. Others for Ill Angels would include: Marc Chagall, Katsushika Hokusai, Cy Twombly, Frida Kahlo, Edward Hopper, Andrew Wyeth, Billie Holiday, Nina Simone, Elizabeth Cotten, Thelonious Monk, Sun Ra, Charles Mingus, Louis Armstrong, John Fahey, Django Reinhardt, Robert Johnson, Chet Atkins, Jerry Garcia, Mississippi John Hurt, Sleepy John Estes, Hounddog Taylor, R.L. Burnside, Akira Kurasawa, John Ford, Sergio Leone, Christopher Smart, Christopher Gilbert, William Blake, Lucille Clifton, Wanda Coleman, Gwendolyn Brooks, Thérèse of Lisieux, Theresa of Avila, Augustine of Hippo, Søren Kierkegaard, Li Bai, Federico García Lorca, Kobayashi Issa, Matsuo Bashō, Rainer Maria Rilke, Jorge Luis Borges.

Some fictional spirits I’d invoke: Prince Myshkin, Anna Karenina, Don Quixote, Pierre Menard, Bartleby the Scrivener, Malte Luarids Brigge, Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi’s Zebra, Helen Dewitt’s Sybilla, Tom Bouman’s Henry Farrell.

In your author note at the end of the book, you mention your retelling of the Book of Job in First Fire, Then Birds and your redaction and translation of a sayings-gospel in Rain Inscription. How did writing those poems prepare you for writing The Gospel? Why do you consider those texts as poems, but you don’t consider The Gospel a poem? How would you compare your book God Bless with your project in The Gospel? Aren’t both projects conceptual poetry? What makes a poem a poem? Where do selection, translation, and arrangement end and invention, imagination, creation begin? (Note: I’m also thinking of some of the things you say in Demonstrategy and As Easy as Lying here.)

HH: Just to reiterate: thank you for this level of engagement, putting The Gospel into a context that includes my previous work. It is an act of intellectual/spiritual generosity, and I am grateful.

For me, this relates to the question we broached above, about genre: maybe my sense that genres are not tidy boxes only reveals how bad I am at keeping my writing in those boxes! But it also has to do with how much of my life experience is mediated experience. I spend a far larger portion of my waking day reading books and scanning screens than I do gazing at where two roads diverge in a yellow wood or listening to gathering swallows twitter in the skies. Consequently, as an attempt to come to terms with my life experience, my writing is more curatorial than diaristic, more about selection and arrangement than about production, more to do with composition than with invention.

We love magical origin stories for our works, according to which the poet or evangelist is the vehicle of a Higher Power—the Muses, or God—who speaks through the writer. But even pop-culture bromides such as “Genius is 1% inspiration, 99% perspiration” work at debunking the magical origin stories. As a poet, I find it liberating to eschew such origin stories: I perceive myself as having more agency if I’m working, not only hanging out, waiting for a visit from the Muse. And the texts themselves of the canonical Gospels indicate that their writers selected and arranged material from sources: in that regard, my Gospel is simply following precedent.

In addition to “mediated” cultural presences animating your poems, there are “immediate” physical presences. Apples, for instance, recur throughout. But it doesn’t feel to me like apple-as-mythic-symbol; it feels more Cezanne-ian or something…

DD: You’re right, there is something impressionistic (or post-impressionistic) about the way the apple recurs in my poems. I love the geometry of apples. I love the sound of the word “apple” and the almost endless number of varietals and their evocative names: imagine an orchard of Empires, a bushel of Jubilees, an Autumn Glory held in the palm of your hand. I’ve always loved apples and being in an orchard. My friend owns an orchard and I helped him plant many of the trees in it. My father dreamed of owning an apple orchard. My grandmother always used to make homemade apple sauce. I don’t employ the apple out of nostalgia, but I am drawn to it; it’s a deep image for me, as it is for many other people.

Last month, I was reading As Easy as Lying, your collection of essays on poetry published by Etruscan Press in 2002. At one moment in that book, you mention that nobody reads your first book anymore, Perfect Hell (Gibbs Smith, 1996). Of course, I immediately bought a copy. I was struck by the way Perfect Hell contains all the wilding seeds that would orchard your oeuvre…Even The Gospel is there, and yet, in many respects, it’s a very traditional debut featuring short lyric poems. This assessment isn’t meant in a derogatory sense; it’s an amazing book, for the dialogue opened through your titles alone. And the poems! (I love “Another Winter, Farther Away” and “Reasons” and “1 Is the Point, 2 the Line, 3 the Triangle, 4 the Pyramid”). The point is, I would never guess that the poet behind Perfect Hell would one day write Chromatic or Rain Inscription or, indeed, The Gospel. Could you talk about your journey from Perfect Hell to The Gospel? How has poetry changed for you? How has poetry changed you? How has the poetry world changed?

HH: One way to respond to this would be to connect it to our earlier discussion of the beatitudes. Perfect Hell tries to perform (its poiesis is) ergon, the root of such English words as work and urge and orgy. The Gospel values mákar more, and seeks to do/be makários. That long-lost me wanted to secure a place in the world, and apparently thought he could. These days, the perplexity more present to the present me is how to let go the world.

When I was writing Perfect Hell, the metaphor of building would have seemed apt to what I thought I was doing; nowadays, the metaphor of mushroom-hunting seems more applicable.

There’s a moment in the Investigations when Wittgenstein says “The real discovery is the one that makes us capable of stopping doing philosophy when we want to.” In my Perfect Hell days, I wanted to be capable of doing. In my Gospel days I want to be capable of stopping doing.

Both books, Perfect Hell and The Gospel, aspire to the attention-to-everything that gives your poems such precision! (“… filigreed like the grip / of a cavalry officer’s pistol / in a black and white western…”) How does one sustain such precise attention?

DD: In As Easy As Lying, you mention that we might think of the training of a poet in the same way that we think of the training of an Olympic athlete (as an ongoing everyday process). You mentioned Fear and Trembling earlier and Kierkegaard’s insight from that book comes to mind: “faith is a process of infinite becoming.” The ongoing training, the infinite becoming, that manifests sporadically as poetry demands this kind of attention. Paradoxically, attaining this type of attention, if not sustaining it, drives such training and becoming forward.

Put more simply: to invoke the awe and wonder you also mentioned earlier, there is so much to love and to uplift and to be stupefied by in this world, there is so much strangeness and grotesquery and astonishment to be undone by in this world, how can a poem not recognize such richness (and such lack) in all its intricate particularity?

In your excellent book on W. S. Merwin, you mention Merwin’s notion that one should find a poet or two to read exhaustively and repeatedly. Besides Merwin, who have been those poets for you? Also, I know we share a love of G. M. Hopkins. I was wondering if you could share some thoughts about him?

HH: I’m sure we all have our lists of those poets whose work has had an especially transformative effect on us, and/or whose work has been an especially lasting presence for us. Hopkins is definitely one of those poets for me. I’ve tried periodically, though so far unsuccessfully, to write an essay about why Hopkins was transformative for me and remains a lasting presence.

At least one element of my response to Hopkins, though, has direct connection with The Gospel. I was raised in a religious tradition committed to the doctrine that divine inspiration has ceased. God spoke through the writers of the books of the (Protestant Christian) Bible, I was taught, but then, once those books were written down, stopped speaking. (I take the point to be, not that God is capricious or has withdrawn from involvement with humans, but that the Bible is complete and sufficient.) But when (in second-semester British Lit, sophomore year, sitting at the plywood desk in my dorm room) I read “The Windhover,” I felt that it was not so. This was the first clear moment of my departure from received religion, the sense “The Windhover” secured to me, that I could not have put into words at that time but did experience viscerally: that inspiration had not ceased, and that if any words were the words of God, those words were.

My religious beliefs are quite different now from how they were at that time, but Hopkins still exemplifies for me the principle that if I want to address what is “higher” than myself, I need to “elevate” my language. If I want to be in touch with what exceeds me, I’d better “language up.”

I hear in your work that same impulse to be in touch with what exceeds you. It’s hard not to take your question addressed to your daughter as a question any poet might ask, so I ask it back to you: “… these lines might not survive / their own inception, but so what?”

DD: For me, as for you, and for most other writers I am sure, we cannot live otherwise. I read and write because I know the truth of John Donne’s “Since I die daily, daily mourn.” I choose to live in the word because it allows me to enter more fully the greater mystery of being alive, in all its unbounded ecstasy and deep sorrow. My reading and writing lives lend me the discipline to try to move beyond the manifold vertiginous fictions of the self, to continue a turning outward, to love more, to more fully be.

What impact has translating, selecting, and arranging The Gospel had on your poetry? What project are you working on now/next?

HH: I hope they have informed one another, been integrated and reciprocal in their mutual influence.

By received distinctions (such as the genres we discussed earlier in this conversation, or disciplinary divisions as they are codified in university departments) my work is a discombobulated mess. And maybe that assessment is accurate! But I experience as unified and coherent the life commitment that received distinctions identify here as poetry, there as translation.

It all feels of a piece to me.

Moving and Mesmerizing: A Review of Robert Wrigley's Nemerov's Door

On the day I received the book, I decided to wade in, reading just one chapter before bed. Instead, I didn’t put the book down until two hours later, having read ten of the eleven essays. You might say that this a book about rivers that pulls you in like a river.

Nemerov’s Door is a collection of eleven autobiographical essays about poetry. It is both moving and mesmerizing. Themes that pop up throughout include family; mortality; politics, nature, man’s relationship to nature, and most essentially, poetry: what it is, how to read it, and why it matters. In form the book is a hybrid: part poetry/part prose; part academic essay/part autobiography; part bildungsroman/part ars poetica; part nature diary/part spiritual meditation.

On the day I received the book, I decided to wade in, reading just one chapter before bed. Instead, I didn’t put the book down until two hours later, having read ten of the eleven essays. You might say that this a book about rivers that pulls you in like a river.

There is an element of hodge-podge among the essays, as if Wrigley threw essays in to fill out the book. You’ll find essays here about My Fair Lady; Frank Sinatra; arrowheads; the Salmon River in Idaho; and the book concludes with a wonderful long poem to Wrigley’s children, largely about Idaho and the state of the nation. But the core of the book, and my favorite part of it, is a series of close readings of the poetry of a handful of modern American poets: Richard Hugo, Edwin Arlington Robinson, Etheridge Knight, James Dickey, and Sylvia Plath.

Early on Wrigley writes that none of these essays would exist if it weren’t for his being a teacher and it is easy to imagine him as an excellent one. About halfway through, I began to feel like Dante being led down the corridors of poetry by Virgil. As a teacher, Wrigley is plain spoken but enthusiastic, esoteric without ever being scholarly or dry. He’s madly in love with poetry and unafraid to say so. (He describes his entry into poetry at age 21 as walking into a cathedral he had passed many times with disinterest). He has an excellent ear and is keenly attuned to the music of poetry which he describes as the condition of poetry. He describes poets as working with the “fierce concentration” of a “ditch digger” or “mountain climber.”

Wrigley doesn’t suffer much hubris. He is aware of his status as a privileged white male, stating in his essay on Etheridge Knight that out of the 39 poets included in Donald Hall’s anthology Contemporary American Poetry, 0 are black women; 1 is a black man; 4 are white women; and and 34 are white males. “Based on the evidence I had at hand, [I deduced poets] were pretty much all white men.“ It is significant then that of the five essays dedicated to close readings of modern American poets, one is devoted to a black poet (Etheridge Knight) and one to a woman (Sylvia Plath).

I entered the Plath chapter with some skepticism, with a feminist feeling of “ok, show me what you’ve got,” but Wrigley did well with the subject, calling the poems of Ariel a kind of “hyper-lucid and incendiary suicide note” whose emotional content is “sheer force” written by an “agonized consciousness” (90) living in a state of “terrified introspection.” Such, he writes, was her “electrified suffering” and the “strange ecstatic horrors” of her situation that she exhibits a “monstrous sensitivity” like Van Gogh’s. In a line that’s flat out funny he writes that if Sylvia Plath were a character in one of his son’s NBA video games, “her every drive on the basketball court would be trailed by flames.” In the last days before her suicide, he writes, “She was on fire. She was in another place. She had left the rest of us behind. She felt more than most of us ever will for any reason....She [was] seeing into the heart of things.”

With the possible exception of the beautifully conducted close reading of Richard Hugo’s “Trout” (“The Music of Sense”), “Nemerov’s Door” is the book’s most powerful essay and is itself more poem than essay. That eponymous essay is a meditation on Wrigley’s relationship with his father, a car salesman with little aptitude for poetry. In the essay father and son blur, passing in and out of each other like ghosts. The “door” of the title is the door of poetry the poet’s father almost supernaturally leads his son to. It’s a mystical essay brimming with love, the strangeness of life, and the fluidity of generations. “Somehow,” he writes, “in all of this you are yourself and you are your father and you are the small boy in Nemerov’s ‘The View from an Attic Window’ coming into the knowledge of time and mortality.”

But what makes the book most mystical is Wrigley’s John McPhee-like appreciation for nature. One of the book’s most striking moments is Wrigley’s description of waking up on a beach with his son and seeing the sky bent down low over them “all eyes and personality,” as if the cosmos were a curious and gentle creature intimately staring at this sleeping man and his son. Another is his description of waking up on a rock in the wilderness to find a group of coyotes staring from a distance, wondering whether he was dead or alive. Another a description of coming upon a bear in the wilderness rearing on hind legs transfixed by a host of yellow butterflies in front of its nose. These glittering images and many more are scattered across the forest floor of this book.

You will get the most out of this book if you are a poet or at least seriously interested in poetry, but in truth, any sensitive person—especially any person in love with the idea of disappearing negatively capable into nature—can be pulled into these essays as easily as into a river you won’t mind floating—or drowning—in.

This Present Moment: A Review of Alan Michael Parker's The Age of Discovery

Parker’s collection is all now. Wherever and whenever the speaker travels, is this present moment.

“For Now”, the opening poem of Alan Michael Parker’s The Age of Discovery, is an invitation, rather, an invocation to the reader as the muse whom the poet aims to court. It segues into “When Everyone Wrote a Poem”, a celebratory roll call of the quotidian. That quotidian is the launching pad that jettisons these poems into discovery of the present. The poet’s age, past the middle, I assume, is the book’s age of discovery. Looking in the rearview mirror to perceive the present.

Parker’s collection is all now. Wherever and whenever the speaker travels, is this present moment. Even when the poet is engaged in reading of Neruda and his mistress’ memoir, Matilde Urrutia is singing now, not then. It is a moment of discovery.

The deeper I read into this collection, the deeper I wanted to go. Parker’s concerns are modern life, automation, displacement, the natural world and God. The mundane magic of the poems, their drifting from voice mail to Polish cupcakes to blue as a unit of measure, captured me. Maybe it was their diction, colloquial and conversational. This poet is always talking—to us, himself, a lover, his future self as a hummingbird—mostly to himself.

Parker’s skills are most apparent in his charming handle on simile: “The dogs snooze on the sofa like session drummers. Like hipsters, the houseplants wait for whatever” and “limoncello viscous as the night.” His shortish lines hug the left margin and are often in uniform tercets; no experiments with white space or punctuation. A poem with almost entirely 3-line stanzas might include one or more quatrain or singlet. Form is secondary to the poem.

“Two Men Disagree, and Row Out to Sea”, opens with “The boat was right for their anger.” This first line, echoed later, has a nursery rhyme bounce and allegorical feel. Its repetition of phrase, of recast line, is reminiscent of a villanelle if Mother Goose had penned a villanelle. Throughout the book, Parker uses repetition deftly. Although the phrase and words that reappear vary, the device creates a familiar pattern and welcome echoes. In the title poem, “and someone” becomes a meme partnered with actions and ways of being that resonate with the speaker and lay bare our connectedness.

Where Parker stands out is with surreal imagery, such as when he writes that watching a painting “was like being a plum”. Or this opening stanza from “Half the World Is Ours”:

Why all the secrets

sewn into the lawns

and into the fields

and into the clouds with needles of light?

Parker has an excellent ear for rhythm and sound that he uses to good purpose. In “The Trains All Arrived”, the stanzas count down 3, 2, 1, in the cadence of a locomotive. The varying meters in these lines from “When I Am a Hummingbird” bounce from iambs to land on a spondee.

I love the dog who leans

matter-of-fact in her need

and the big smile of the small Pit Bull

The speaker isn’t always alone in these poems. Characters in the poems are often strangers. The character of the driver in “The Ride” is “a girl who needs a listener”, as she blathers on injecting serious news she must share. Overall, this collection is conversational in tone; big news is dropped in like mail through the slot of the front door.

There is a lot of delight and humor in The Age of Discovery. Comparisons might be made to Billy Collins or Ron Koertge, but Parker is more relaxed than Collins and more acerbic than Koertge. Any sweetness tasted here is mellow, warm, never cloying. Parker’s poems are freewheeling. Less confined to regular lines they may veer into a heady space or the sky or the heart. “Later, Love” opens with “Who among us has just had sex?”

I believe this speaker. As a young reader I gravitated towards James Baldwin and Carson McCullers. It was the authority in their voices, in short stories, novels, essays, that drew me to them. Parker’s voice has a similar effect on me. Out of the blue statements, magical thinking-like, surrealistic, yet I believe them. I hear that voice most loudly and assuredly in “Neruda on Capri”, an 8-part poem. It is the center of book literally and figuratively. It is part narrative, part meditation and borrows lines from Matilde Urrutia’s memoir.

On the heels of “Neruda on Capri” comes “A Fable for the Lost”. I wondered if it is a commentary on the preceding poem. After the less formal shape of the Neruda poem, this “Fable” is bold on the page with tercets leading with anaphora, opening phrases that act like an incessant kickstart to what the fable might possibly be about.

The litany of “Egypt, North Carolina” takes a turn in the second unprayer-like stanza:

Soon, it will be my time.

I’ll take out the trash,

ill-fated as any Pharaoh,

and stand myself in the can.

“The New World” follows with the humming of a hymn and an unknown woman crossing herself. The world, or at least the speaker’s reality, becomes an ark for this collection of the public that is a diner. Parker holds a taut line here where we, prodded by TV—a character in this poem—cannot surrender our suspicion that someone has a gun.

“When the Moon Was a Boy” repeats phrases and we hear another nursery rhyme at its core.

and he wanted to give the sun a pear,

and he wanted to give the wind a pear,

and he wanted to give the rain a pear,

The speaker in these poems has been around the sun long enough to know what daybreak can bring. “Hold still, the whole scene says, before the sun drives in the first nail”, he writes in “Aubade with Two Deer”. Lacking nostalgia, the poems have a knowing wisdom that is sometimes self-mocking and at other times exquisitely, magically sage. Knowing what daylight can bring, means knowing what it has brought. These are twilight poems. Anyone who has had a colonoscopy understands the twilights that its process and its anesthesia evoke—being of an age to have the procedure and the quasi-existence of the twilight sedation where one is sort of aware, but not really. Therefore, Parker’s “Psalm”, which is akin to a Shaker hymn, is a perfect ending for this collection. It is a bedtime story, a kiss goodnight.

A Review of Four Quartets: Poetry in the Pandemic

Three deep bows to the editors of this rainbow, this cornucopia, this star-studded cast of gifted poetry makers. . . . On page after page, they invite the reader to view this pandemic through a renewing prism. COVID-19 will be fuel for all kinds of art in the future; kudos to these poets for writing insightfully about something so immediate.

Three deep bows to the editors of this rainbow, this cornucopia, this star-studded cast of gifted poetry makers. They did not trick out the poetry with fancy fonts or graphics; the words speak for themselves and that feels right.

At least one poet had the virus, some are old, some young, some write in pairs, one has been translated from Korean. One displays show-don’t-tell photographs. On page after page, they invite the reader to view this pandemic through a renewing prism. COVID-19 will be fuel for all kinds of art in the future; kudos to these poets for writing insightfully about something so immediate.

Each poet deserves to be experienced as to style, format, historicity, influences, philosophy, and more, but a book review must, regretfully, skip through this rich trove with but a few brush strokes for each. Perused at your leisure. There is so much to think about, so much to savor. If you think you know this pandemic, think again.

Jimmy Santiago Baca’s first people’s heritage thumps through his poems. The archetypal buffalo brings us back to the real, the power, the spiritual bedrock.

Gentle heart you are,

I would say

Sumo-sweetness, the prairie breeze

So bracing it recalls your soul

To times you ambled in amber citrus fields…

Sumo-sweetness, what a way to describe the heavy, powerful, surprisingly lithe buffalo!

Yusef Komunyakaa and Laren McClung, teamed up. Their lush language encompasses all living matter, from the moment when creatures emerged from the swamp to today, from here to Papua, New Guinea. One poem stops to witness “the way a coyote or band of raccoons/might wander out of Central Park/up Fifth Avenue & climb the MET steps.” Here. Now. The pandemic world is just one of their many, but “Don’t worry, love, there’s nothing in the world of mirrors that is not you looking back…”

Stephanie Strickland’s poems are notional.

Belief

in

The existence of other human

beings as such

is

love

The punky, punchy groove climbs into the reader’s head and bounces around until it lands someplace, and you say, “Yeaahhhhhh.”

Mary Jo Bang’s poems creep in at a petty pace: today, today, today. “Today I thought time has totally stopped. There is no/foreseeable future and the present so overwhelms the past/that it hardly exists.” She presents Purgatory, neither here nor there, a dreadful aloneness. Her head is “Kafka’s crawl space in/which something alive is always burrowing.” “The world is too much,” she writes, “too much with me.”

Shane McCray’s poems feel like they fell off the back of a truck. He tosses off his observations in delightful, unexpected, well researched detail. While skateboarding, he is in a “city where there isn’t/A city anymore.” He inhabits his physical self “as if my body were haunting my body.” Things are not as they were, as they seem, or even as he can properly understand them, which gives him a chance to become something new. His poems reveal great intelligence but little salvation, perhaps some guideposts to understanding.

Ken Chen is discursive, fluent, erudite, political. He sees out today’s Apocalypse unfolding “under the sallow iPhone lamp…Shout over the police who have prohibited even breathing…the planet spools out its fraying thread of days…where they threw hoses at prisoners and led them into the burning forest…” Chen’s recitation of horrors flows on, from the obscene photos of the dead boy on the beach in Bodrun to some cute deaths involving Harry Potter and Minnie Mouse. He exhorts the reader to remember them: “I inspected each name and mounted them in the bezels of the text.” There is a surprise ending. Chen snaps his fingers, “what we remember/replaces what remains, the lost are soon forgotten, and We hold hands, we run,/we leap into the waters.” May it be so.

J. Mae Barizo offers the prayer that “…the light/will lick and lick the damage clean. That it is not/ruin already.” She ushers the reader through first poems filled with flowers and light, into a place where the prognosis is poorer. Her metaphors are delightful: “outside the pedestrians gleamed like pinpricks, or listening to lovers/sleep, breathing/like monster trucks.” Her spirit cannot resist hope despite evidence to the contrary, and the reader is taken on a soft-loving ride through the ruins.

Dora Malech tours the headlines of this dire time, writing as if in a diary. She reminds us of the little girl who drowned on her father’s back as he tried to cross the river to America, of the penguins starving in the winter, torahs. She writes “I had waded into the Information and come back dragging a/haul of names. Still soaked, they marked a trail in the sand/behind me as I pulled them from the River.” Malech is trying to keep up her hope while suffering in the strange, unexpected ways that we are all suffering.

Smack dab in the middle of the book comes B. A. Van Sise with his photographs. A welcome visual break. They are evocative, not pretty. Why is that man the only one not wearing a mask? Why is that other man clutching his child with such sad determination? Hail to that essential worker, serving in the boring convenience store to save us. Thank you, editors Kristina Marie Darling and Jeffrey Levine, for including these photos among the poetry.

Jon Davis is an old man with nothing to lose. Might as well tell the truth as he sees it. He confronts the pandemic and learns what he already knows, only more so. Life is an uncertain enterprise. He mentions the “layers of history”, recalling the work of another elderly poet, Stanley Kunitz and his poem The Layers. Such is impermanence—layers of good on bad, rich on poor, happy upon unhappy. He rewards us with humor: “we remembered the ‘kids’ were thirty-something…speaking a language we didn’t recognize at all.” And how about this, “the skunks ambled through the arugula like mental patients.” Favorite metaphor: “…music seeping into the lobby like radiation.”

Lee Young-Ju’s work is translated by Jae Kim, and bravo to him. It couldn’t have been easy. If Salvador Dali had written poetry, it might be like this, full of trompes d’oeils, flippant about the rules, running through a place that is familiar but not like anything you’re ever seen.

Lee is Korean, and her poems have sieved through a different history, a different culture. As in much Asian art, there is no attempt to keep time and space in perspective. The poetry is made of images, smells, wind on the skin. “Languages are afloat, like feathers,” or “What’s this breeze that has leaked out of my soul?,” or “Girls gather in the alley and talk without moving their lips.” The reader can see, hear, and feel it, and the rhythm and pungency carry her along, as if she were in the blind tunnel at the amusement park. Though some images are of wreckage and despair, they’re still yummy. “I remain in the whirlwind and continue to be thrown away.”

Rachel Eliza Griffiths is another prose poet. Reading her work is like going to the spa; every touch, smell, warmth, and chill is palpable, meaningful, and healing. She addresses the pandemic in its atomic expression, taking us through the near death feelings when engulfed by a 103-degree fever. She shows us the virus from inside the body of a person suffering from it. She wonders, “Will I come through this if my body does not come with me?” She honors Tamisha, the forensic technician who places daffodils on body bags in the hospital morgue. In a bow to another aspect of our times, she remembers the Black lives lost. She steps back from the atomic in the end to comment, “The virus rears in sunlight, devouring bodies that will not mask, separate, isolate, listen. The virus is the arrow of the nation’s ego.”

A.Van Jordan’s poetry skims along accessible, meaningful. He encounters quarantined, sheltering people and “I ask them/and—is it possible, for the first time?—/I truly wanna know” echoing Meghan, Duchess of Sussex’s recent op ed that pleads with us to ask each other in this perilous time, “How are you?” Jordan picks and chooses his vocabulary and his allusions. He “hangs out,” talks of “swagger,” then he turns to Prospero, Caliban, Queen Elizabeth I, Shakespeare. His comparison of the words of Queen Elizabeth I and Donald Trump is a walloping riposte to those who dismiss racism and repression. Yes, this has been going on a for a long time. He quotes Langston Hughes, “I dream a world.” The juxtaposition of the high-fallutin’ with the everyday jolts the reader into acceptance of universality. Can’t keep this man down. “[.]..we continue long into night/into the coming day, a Soul Train of revolt/lining rural routes, and filling streets/in our cities with dance.”

Maggie Queeney writes “Inside the Patient is another Patient, perfect, and one/size smaller. Inside that Patient is another, and another,/perfect.” A poetic symphony of compassion for the suffering, the lost hopes, the destruction of what should have been. The patient is delivered “Into the hands of others, their palms slick with/alcohol or cloaked in latex in a blue chosen/for its quantified calming effect…” Queeney is writing what she knows, catching fragments of reality, of truth, and laying them on a silver platter for us.

She kneads the subject of “Patient” into many shapes, each enlightening, the words lovely and clear. “The Patient’s Book of Saints,” “The Patient has a History of Medical Treatment,” “The Narrative Arc of the Patient,” and so on. Not only does the situation of the Patient change, but the structure of her poems changes as she paints each with a different brush. If Queeney hasn’t been trained as a nurse, she sure feels like one, detail-oriented, caring, effective, sure.

Traci Brimhall & Brynn Saito are co-authors who sink into the senses, colors, and impressions of life, but yearn for certainty, for the power to protest. Theirs is a record of the isolation of the pandemic, but they also bring along the rising waters of climate change and the rife injustices that remain unaddressed. Ruin awaits. So what do you do?

Dusk summons me home with its sapphire curfew.

Do you want to know how I do it? I expect nothing.

And then, and then, the bright surprise of your arrival.

A poet cannot give up hope; it is her substance, her living. Who would bother to distill the essence of things if not to inspire others to rise above themselves and save us?

Denise Duhamel jumps right in: “I saw the best minds of my generation (i.e., Fauci, Birx)/Undermined by Trump….” This poem is titled “Howl,” a reference, perhaps an homage, to Allen Ginsberg. Just when you thought you’d heard the first draft of history told in every possible way, she comes up with a new way. She condenses the tiresome facts into an energy pill, then repeats: canceled doctors’ visits, essential workers, no visits to mom, masks. Duhamel pummels the reader again and again. “2020/always sounded to me like a sci fi year/but now it is here with a pandemic predicted/by both scientists and sci fi.” That doesn’t sound like poetry, but in Duhamel’s hands, it is. Here is our Samuel Pepys. Here’s the bam bam bam, and then bam, bam, bam, of indignity, sacrifice, loneliness, helplessness, the revitalization of Nature as everybody stays home, the lies, the needless death, the brutality—read on.

Rich Barot is the perfect final act, a series of effortless (lol, as if), funny, insightful, touching poem-paragraphs full of images, turns of phrase, palpable reality. Here is the last of them:

During the pandemic, I listened. Things hummed their tunes.

The pear. The black sneaker. The old-fashioned thermometer.

The stapler with the face of a general from Eastern Europe.

Once, my father confessed he had taken the padlock from his

Factory locker and clipped it on the rail of a footbridge at the

Park. He had retired. The park was near his house. Each time

He went there, I imagined him feeling pleased, going to work.

*

This review is but a tiny taste of a novel and enchanting work. Keep it at your bedside for a laugh, a tear, a thought, an inspiration.

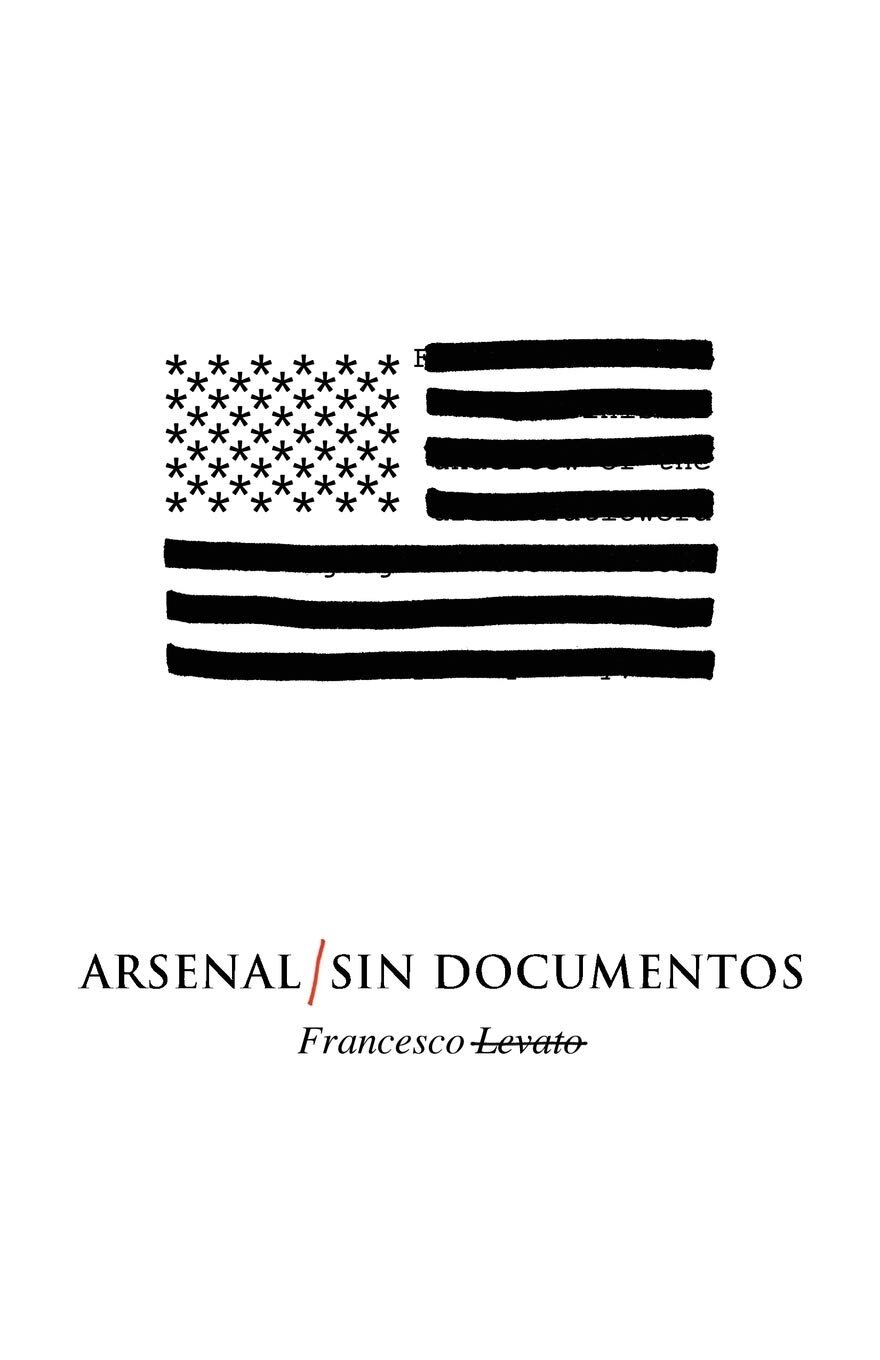

A Review of Francesco Levato's Arsenal/Sin Documentos

Francesco Levato has created a disquieting and challenging book that provokes more questions than answers.

Francesco Levato has created a disquieting and challenging book that provokes more questions than answers. Reading the book pulled me into a dialogue with it, almost an argument, questioning it as much as it questioned me, challenging me as I challenged it. The book fits into no easy categories, and describes itself as “a work of poetry and concept art." This is an apt description.

The title, Arsenal/Sin Documentos, packs a lot of information about the book. It is nearly a complete summary. The slash cuts the title in two, apposing English with Spanish in a dialectic juxtaposition. Arsenal is an English/Spanish cognate, and according to the Merriam Webster Dictionary, it means “an establishment for the manufacture or storage of arms and military equipment.” The word can also refer to a store, repertoire, or set of resources without necessarily denoting weaponry; as for example, “she had developed an extraordinary arsenal of mathematical techniques.”

The right side of the title, the part following the slash, ‘Sin Documentos,’ is Spanish for ‘without documents.’ This seems an explicit denial of fact for the book is itself undeniably a document. Moreover, the book consists almost completely of official U.S. Government documents. So, the title, Arsenal / Sin Documentos, is a paradox that works simultaneously on multiple levels.

Sin, that prominent middle word has the joy of living in both languages, but with different meanings in each. Clearly, sin connects the left half English word directly with the right half Spanish one. Sin sits between them like a fulcrum, balancing the left and the right hand parts of the title in a kind of sour bilingual pun. The title connects documents, their absence, weapons, and sin.

The cover of the book displays a couple of graphic elements that reflect the core of the book, its purpose and message. One of these graphic elements is the way the author’s name is printed. While the first name, Francesco, is in normal text, the family or surname is in bold font with a strikethrough; i.e., Levato. The visual impact of the strikethrough, featured on the cover, prominent under the title, is visually disturbing, bizarre, and absurd, which is consistent with both the core message of the book as well as the compositional techniques Levato uses.

Roughly about half the pages in the book contain text that, not only has a strikethrough, but been completely obliterated with a thick, heavy, black marker pen. On flipping through the book, the effect is undeniably eye catching and dramatic. These pages look as if an outraged state censor, intent on demonstrating his fury, worked these pages over. Page after page contains text that is completely unreadable. These are not polite, carefully executed erasures. These pages have been violently obliterated. The visual impression these pages communicate is the intentional destruction of the text; they are a visual embodiment of anger. They look like the product of an imperious totalitarian government. The anger works on two levels. One level is Levato’s own rage at the text of the government documents he obliterates. The other level is the subtext of emotion and affect contained in the original government documents themselves that provoke Levato’s rage. Notes at the end of the book state that the “. . . book consists of a series of linked documentary poems composed of appropriated language from U.S. government documents such as: Customs and Border Patrol handbooks, the Immigration and Nationality Act; the U.S. patent for Taser handheld stun guns,” and so forth.

Levato structured the book into fifteen parts, each part beginning with an untitled but numbered policy statement, ranging from Policy .01 through Policy .15. Each of these policy statements is followed by one, two, or three additional documents on a variety of topics, some in Spanish, some in English. This organization parodies the government documents and the bureaucracy that produces them. The book’s index displays the book’s general outline and organization, with the numbered policies, sections and subsections, definitions and so forth, mercilessly printed in a standard government format and font that is intentionally designed to minimize any sense of humanity and to discourage reading. Importantly, these documents form part of the government’s arsenal of regulations, policies, procedures, and other weaponry employed to secure our borders. The documents describe the specific levels of violence acceptable for the enforcement these policies; and in the process of enforcement, apprehending, harming, brutalizing, criminalizing, and if necessary, killing the alien morphed to victim/villain. Levato uses these texts as a canvas on which to expresses his rage at the text and what it embodies. Thus, the book is a collection of Levato’s passionate abstract expressionist sketches of anger and outrage reflected back onto the text that itself embodies anger and outrage. In this respect, the book is more a work of visual art than of linguist art.

The cover has still more to say about the book. A large portion of the cover is devoted to a black and white rendering of the American Flag. The fifty stars are fifty black asterisks. The flag’s thirteen horizontal strips, normally alternating red and white, are rendered in black and white, the black being another heavy black maker pen redaction, completely obliterating whatever is under it. Thus, the cover, with the strikethrough, the heavy blacked out redactions, and the reference to a caricatured nationalism of the flag, displays several main compositional elements of the book. These elements include the obvious fact that everything in the book is printed in black and white, not only on the page but also in its world view.

Not all of the pieces of the book are dramatically overwritten and blacked out. A much smaller number of documents appear so faintly on the page they are virtually impossible to read with the exception of a few words scattered here and there. These pages of faint text contrast with the black heavily marked out text that dominates the book. The faint, disappeared text reminds us not only of how privilege afforded to the wealthy is visibility while poverty is assigned invisibility; but also, the disappeared text calls to mind the disappeared. With these faint texts, Levato manages to evoke the disappeared, to call attention to those missing. He makes this move with great subtlety, so we pause and mourn.

This book has an absolute unity of purpose and singleness of vision. It realizes an overarching inspiration and design. It is by no means a collection of separate individual pieces; rather, it is a single unitary creation. The document’s appearance on the page, its physical embodiment contains, illustrates, and conveys its meaning. This 151 page book, in its entirety, is more like a passionately conceived, concrete poetic monograph than anything else. It is a convincing, deeply satisfying, compelling, yet emotionally disturbing document to spend time with. I have never encountered anything quite like it.

An Interview with Matthew Thorburn, author of The Grace of Distance

The poems in The Grace of Distance have to do with a variety of distances—between people, between cultures, between different physical places in the world, between faith and doubt—as well as the sense of perspective and understanding that can come with distance, whether it’s a matter of physical distance or time passing.

Marcene Gandolfo: I read The Grace of Distance in the summer of 2020, and your poems, which meditate so eloquently on the very nature of distance, spoke to me with a profound immediacy and relevance. Of course, I know that you composed these poems long before you knew of the impending pandemic or the social distancing that would ensue. Still, can you speak to the collection’s current relevance? From writing these poems, have you acquired insights that help you face challenges in these uncertain times?

Matthew Thorburn: Thank you for asking—that’s a very timely question, and something I’ve thought about too. The poems in The Grace of Distance have to do with a variety of distances—between people, between cultures, between different physical places in the world, between faith and doubt—as well as the sense of perspective and understanding that can come with distance, whether it’s a matter of physical distance or time passing. That’s what I was thinking about as I wrote these poems over quite a few years, and certainly when LSU Press published this book in August 2019.

But it is strange, isn’t it, to think about how the word “distance” has taken on such a different meaning this year? So many people are enduring all kinds of terrible hardships right now—whether it’s sickness, caring for a loved one who’s ill, financial hardships, loss of employment, or other personal difficulties. I can’t help thinking of distance in terms of the loved ones who I’m not able to see right now, such as my parents and aunts and uncles, as well as many friends. Spending time by yourself has its virtues and can lead to a kind of grace, I think—as a writer, or even as a reader, this seems especially true—but being separated from family and friends is a hard (though right now very necessary) thing to do.

However, I also know I am immensely lucky that my parents and other loved ones are healthy and doing okay, and I am very fortunate that I’m able to do my work from home. Spending most of this year working from home has meant much more time with my wife and son—the opposite of distance—which has been an unexpected gift. I try to keep that front and center in my mind and just take things day by day.

MG: Can you say something about your composition process? Do you write daily? Do you engage in writing rituals? In particular, what role did this process play in the construction of your book? In particular, how did the theme of distance emerge?

MT: Prior to the pandemic, I did most of my writing on mass transit, during my commute from my home in New Jersey to my office in New York City, and back. I also had a good routine of working on poems during my lunch hour. Each day I would carry printed copies of poems I was currently working on, and I’d mark these up with edits during those times. Then I’d type in my edits at home, print clean copies, and do it again the next day. Or if I was working on a manuscript, I’d carry a copy of that in my briefcase to reread and mark up. It might not sound ideal, but this writing practice worked very well for me. It’s how I wrote many of the poems in this book—and these days I sometimes daydream about my favorite spots in midtown Manhattan where I could sit outside to eat my lunch and work on my poems.

The Grace of Distance originated in a file folder where over the years I saved poems that didn’t make it into my previous books—mainly for thematic reasons—but that I thought were still very good poems and wanted to keep. (There were also a handful of shorter poems I’d written while working on my book-length poem, Dear Almost.) Eventually, as that folder grew thicker, I read through these poems again and came to see that they hadn’t fit into those other books because almost all of them were about something else—those different kinds of distances. Once I recognized that, I continued writing new poems with this theme in the back of my head.

MG: In “A Poem for My Birthday,” you write, “ . . . “Whatever happened / to longing, you ask, but I long for that / red barn town where I was born . . . ” As these poems continuously travel, do they unremittingly search for home, escape from it, or simultaneously do both?

MT: I think they probably do both. As someone who grew up in one place (the Midwest), then lived for nearly two decades in a very different place (New York City), and now lives in still another different-feeling place (small-town New Jersey), my sense of “home” is complicated. I find myself looking back to Michigan, as in the poem you quoted, as well as writing poems that are set in and focused on the landscape where I live now. When it comes down to it, if you said “home” to me I’d probably picture Lansing, Michigan, where I grew up—though I have to tell you, after nearly three years here in central New Jersey, I feel very much at home here too.

Having said that, though, I find that it often works best for me to be somewhere other than the place I’m writing about—to be looking back at where I’ve been, to have that distance. And certainly, as I get older, I find myself writing more about the past and childhood memories. This is probably why this theme of distances came so naturally to me—why I discovered I’d actually been writing poems about it for years!

MG: In the collection, several poems explore the role of art in bridging interpersonal distances between time and space. Could you elaborate your thoughts on this subject?

MT: I love writing poems about visual art, especially paintings, as well as about music. I’m really drawn to the stories that works of visual art can suggest. And it amazes me to stand in a museum and look up close at a painting and think about the fact that Vermeer once stood in a similar position and put this paint on this canvas. To me that suggests a distance that expands and contracts all at once. As I describe in my poem “Forgotten Until You Find It,” seeing the Girl with A Pearl Earring at the Frick Collection was a powerful experience for me.

In writing a poem I want to share something—to try to enable the reader to see what I’m seeing and feel what I’m feeling (even if those sights and feelings are ones I’ve imagined). I think it was Philip Larkin who said a poem is like a river you can step into in the same place again and again. There’s a sense of connection I feel in reading the poems I love best, or looking at paintings I love, and I hope I am able to create something like that in my poems too. Paintings are made to be seen, usually, just as poems are usually written with the intention that others will read and hear them—so I think that’s something we have in common.