A Review of Susanna Clarke's Piranesi

Like Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, Clarke’s 2004 bestseller, Piranesi is a novel of enchanting world-building and detail, and a novel that is itself enchanted by the pursuits of knowledge-seeking and knowledge-sharing.

Piranesi, the title character of Susanna Clarke’s new novel, has appointed himself explorer and archivist of his world—an apparently endless labyrinth of stone halls lined with enigmatic statues. A vigorous sea sweeps through the lower level of the house; cloud, mist, and rain roam the upper level; stars shine through the windows at night. As far as Piranesi knows, he is the only living inhabitant of his world but for one: the Other, an academic who believes that the House holds a forgotten knowledge which can be used to unlock powers of flight, shape-shifting, and telepathy long lost to humankind.

Like Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, Clarke’s 2004 bestseller, Piranesi is a novel of enchanting world-building and detail, and a novel that is itself enchanted by the pursuits of knowledge-seeking and knowledge-sharing. Jonathan Strange layered speculative elements over a realist framework of Georgian social dynamics, emphasizing power relations and socially enforced silences. In Piranesi, Clarke has focused on a setting that reconfigures aspects of human experience and the natural world into abstract forms; a setting that recalls the parallel world on the other side of the rain to which the magicians of Jonathan Strange disappear.

Jonathan Strange is heavily footnoted, so that the novel itself could seem to be one of the volumes of magical history to which the narrator refers. Piranesi, too, is conceived as a found object, as if it has grown freely out of its own setting. The novel is structured as a series of journal entries, leaving the reader reliant upon Piranesi’s observations as a window into his world. Luckily, Piranesi is a generous observer and a meticulous notetaker: “As a scientist and an explorer,” he tells us, “I have a duty to bear witness to the Splendours of the World.” Clarke narrates so brilliantly through Piranesi as to turn his keen eye for detail and tendency toward pompousness into stylistic flourishes.

Piranesi’s frequent interrogatives make the text rich with a kind of loneliness more akin to wonder than to moodiness. “When I feel myself about to die, ought I to go and lie down with the People of the Alcove?” he writes, referring to a set of skeletons that he has discovered in the House, and to which he—like an acolyte—administers offerings of food, drink, and flowers. “What is a few days of feeling cold compared to a new albatross in the World?” he writes, as he sacrifices the dried seaweed that he burns to keep warm for a family of albatrosses that has made its home in his Halls. Piranesi’s narration is fascinated by the interconnectedness of things, and by Piranesi’s own place in the web of being that includes skeleton, albatross, statue, and sea.

The pages of the novel are studded with clever details and found objects, and part of the delight of wandering Piranesi’s Halls is in finding and listening to them. Listening to them because—though Piranesi is a distinctly quiet novel, punctuated by terse conversations between characters who tend to conceal as much as they share—every object that we discover in its pages is gorgeously in conversation with Piranesi’s universe. There are the pieces of torn-up notes found stashed in birds’ nests—evidence of a human mind in distress. There are the bottles of multivitamins and slices of Christmas cake that the Other occasionally offers to Piranesi, which suggest the existence of a world external to the House. There are the “seashells, coral beads, pearls, tiny pebbles and interesting fishbones” that Piranesi weaves into his own hair, physical manifestations his oneness with the House, which other characters would likely call his madness.

Piranesi is a thriller at times, with moments of fast-paced action and occult intrigue—but it is the interaction between Piranesi and his setting that makes the novel illuminating and memorable. Like one of Borges’ labyrinths, Clarke’s infinite house of statues is a meeting point between human consciousness and indifferent cosmos; between meaning-making and wild-beyond-meaning. As Piranesi and the Other navigate this liminal space, Clarke shows us different ways of thinking about knowledge and the natural world.

Piranesi identifies himself as an explorer and a scientist, but also as the “Beloved Child of the House”—because Piranesi’s way of knowing is also a way of loving, a way of receiving love. Piranesi’s ways of knowing are numerous: he explores the Halls by foot and notes the statues he encounters; he records patterns of star and sea, and so makes sense of the terrible tides; he talks to, and receives messages from, birds and statues. Clarke uses Piranesi as a model of knowing, and reminds us that there are areas of overlap between knowing and loving: Both ways of relating to the world can involve attentiveness and wonder.

Piranesi soon comes into conflict with the Other over the latter’s search for exploitable knowledge. Piranesi worries that this model of knowledge-seeking leads the seeker “to think of the House as if it were a sort of riddle to be unravelled, a text to be interpreted.” This objection to the Other’s motivations is not a denunciation of scientific pursuit (Piranesi, after all, is an avid mapper of stars and predictor of tides); instead, it is an intellectual cringing-away from the kind of science that views the universe as dumb stuff. To Piranesi, the universe is active—infinite in its beauty and kindness—and the worthwhile ways of knowing the universe are those which put him into greater harmony with it.

One of the few missed opportunities in Piranesi is the novel’s failure to locate its literary discussion of “madness” in relation to contemporary discourse about mental health or cognition. Clarke’s romantic treatment of madness (which is related to both childhood cognition and melancholy, and which opens the mind to magic) feels at home in the Georgian context of Jonathan Strange. It seems disappointing, though, that Clarke’s treatment of madness has not evolved in Piranesi: Though several characters are contemporary academics, discussions of Piranesi’s state of mind are conducted in the same, general, poetical terms as in Jonathan Strange.

Piranesi’s prolonged stay in the House, we learn, has caused him to suffer from memory loss and other side-effects. Piranesi, however, does not sense any disconnect between his consciousness and the totality of things. “The World feels Complete and Whole, and I, its Child, fit into it seamlessly,” he writes. “Nowhere is there any disjuncture where I ought to remember something but do not, where I ought to understand something but do not.” Piranesi’s state of mind (his memory loss, his dissociation from his former identity, his familial feelings toward birds and statues), which other characters call madness, seems to go hand-in-hand with his ability to understand the House.

Madness figures into Piranesi as a literary device, as it does in Jonathan Strange or the Romances of Chretien de Troyes. Given the cleverness with which the novel resolves some of the other puzzles of relation between the normal, human world and the House, it seems a shame that Clarke has not weighed in more explicitly regarding the extent to which Piranesi’s cognitive state might connect to something literal.

There are also moments of awkwardness toward the end of the novel, when the action between characters becomes the central focus of the narrative, and Piranesi’s relationship with the House seems to take a backseat. The narrative’s sudden insistence on straightening out Piranesi’s literal circumstances (on the Resolution of the Plot, as Piranesi might write) feels a rude awakening after we have been so happily immersed in the mysteries of the House, which ought to evade resolution.

Piranesi is a shapeshifting, dynamic creation that keeps the reader guessing as to what kind of thing, exactly, it is. It is a book about magic and alternate worlds, and also a book about science and learning. At the core of the novel is an abstract conflict that transcends human action; yet the pages are too saturated with Piranesi’s emotive consciousness to read as a straightforward, disinterested allegory. Gorgeously imagined and meticulously constructed, generous and sharp, it is one of those rare books that cuts through the heart of things but leaves that heart beating.

A Review of Four Quartets: Poetry in the Pandemic

Three deep bows to the editors of this rainbow, this cornucopia, this star-studded cast of gifted poetry makers. . . . On page after page, they invite the reader to view this pandemic through a renewing prism. COVID-19 will be fuel for all kinds of art in the future; kudos to these poets for writing insightfully about something so immediate.

Three deep bows to the editors of this rainbow, this cornucopia, this star-studded cast of gifted poetry makers. They did not trick out the poetry with fancy fonts or graphics; the words speak for themselves and that feels right.

At least one poet had the virus, some are old, some young, some write in pairs, one has been translated from Korean. One displays show-don’t-tell photographs. On page after page, they invite the reader to view this pandemic through a renewing prism. COVID-19 will be fuel for all kinds of art in the future; kudos to these poets for writing insightfully about something so immediate.

Each poet deserves to be experienced as to style, format, historicity, influences, philosophy, and more, but a book review must, regretfully, skip through this rich trove with but a few brush strokes for each. Perused at your leisure. There is so much to think about, so much to savor. If you think you know this pandemic, think again.

Jimmy Santiago Baca’s first people’s heritage thumps through his poems. The archetypal buffalo brings us back to the real, the power, the spiritual bedrock.

Gentle heart you are,

I would say

Sumo-sweetness, the prairie breeze

So bracing it recalls your soul

To times you ambled in amber citrus fields…

Sumo-sweetness, what a way to describe the heavy, powerful, surprisingly lithe buffalo!

Yusef Komunyakaa and Laren McClung, teamed up. Their lush language encompasses all living matter, from the moment when creatures emerged from the swamp to today, from here to Papua, New Guinea. One poem stops to witness “the way a coyote or band of raccoons/might wander out of Central Park/up Fifth Avenue & climb the MET steps.” Here. Now. The pandemic world is just one of their many, but “Don’t worry, love, there’s nothing in the world of mirrors that is not you looking back…”

Stephanie Strickland’s poems are notional.

Belief

in

The existence of other human

beings as such

is

love

The punky, punchy groove climbs into the reader’s head and bounces around until it lands someplace, and you say, “Yeaahhhhhh.”

Mary Jo Bang’s poems creep in at a petty pace: today, today, today. “Today I thought time has totally stopped. There is no/foreseeable future and the present so overwhelms the past/that it hardly exists.” She presents Purgatory, neither here nor there, a dreadful aloneness. Her head is “Kafka’s crawl space in/which something alive is always burrowing.” “The world is too much,” she writes, “too much with me.”

Shane McCray’s poems feel like they fell off the back of a truck. He tosses off his observations in delightful, unexpected, well researched detail. While skateboarding, he is in a “city where there isn’t/A city anymore.” He inhabits his physical self “as if my body were haunting my body.” Things are not as they were, as they seem, or even as he can properly understand them, which gives him a chance to become something new. His poems reveal great intelligence but little salvation, perhaps some guideposts to understanding.

Ken Chen is discursive, fluent, erudite, political. He sees out today’s Apocalypse unfolding “under the sallow iPhone lamp…Shout over the police who have prohibited even breathing…the planet spools out its fraying thread of days…where they threw hoses at prisoners and led them into the burning forest…” Chen’s recitation of horrors flows on, from the obscene photos of the dead boy on the beach in Bodrun to some cute deaths involving Harry Potter and Minnie Mouse. He exhorts the reader to remember them: “I inspected each name and mounted them in the bezels of the text.” There is a surprise ending. Chen snaps his fingers, “what we remember/replaces what remains, the lost are soon forgotten, and We hold hands, we run,/we leap into the waters.” May it be so.

J. Mae Barizo offers the prayer that “…the light/will lick and lick the damage clean. That it is not/ruin already.” She ushers the reader through first poems filled with flowers and light, into a place where the prognosis is poorer. Her metaphors are delightful: “outside the pedestrians gleamed like pinpricks, or listening to lovers/sleep, breathing/like monster trucks.” Her spirit cannot resist hope despite evidence to the contrary, and the reader is taken on a soft-loving ride through the ruins.

Dora Malech tours the headlines of this dire time, writing as if in a diary. She reminds us of the little girl who drowned on her father’s back as he tried to cross the river to America, of the penguins starving in the winter, torahs. She writes “I had waded into the Information and come back dragging a/haul of names. Still soaked, they marked a trail in the sand/behind me as I pulled them from the River.” Malech is trying to keep up her hope while suffering in the strange, unexpected ways that we are all suffering.

Smack dab in the middle of the book comes B. A. Van Sise with his photographs. A welcome visual break. They are evocative, not pretty. Why is that man the only one not wearing a mask? Why is that other man clutching his child with such sad determination? Hail to that essential worker, serving in the boring convenience store to save us. Thank you, editors Kristina Marie Darling and Jeffrey Levine, for including these photos among the poetry.

Jon Davis is an old man with nothing to lose. Might as well tell the truth as he sees it. He confronts the pandemic and learns what he already knows, only more so. Life is an uncertain enterprise. He mentions the “layers of history”, recalling the work of another elderly poet, Stanley Kunitz and his poem The Layers. Such is impermanence—layers of good on bad, rich on poor, happy upon unhappy. He rewards us with humor: “we remembered the ‘kids’ were thirty-something…speaking a language we didn’t recognize at all.” And how about this, “the skunks ambled through the arugula like mental patients.” Favorite metaphor: “…music seeping into the lobby like radiation.”

Lee Young-Ju’s work is translated by Jae Kim, and bravo to him. It couldn’t have been easy. If Salvador Dali had written poetry, it might be like this, full of trompes d’oeils, flippant about the rules, running through a place that is familiar but not like anything you’re ever seen.

Lee is Korean, and her poems have sieved through a different history, a different culture. As in much Asian art, there is no attempt to keep time and space in perspective. The poetry is made of images, smells, wind on the skin. “Languages are afloat, like feathers,” or “What’s this breeze that has leaked out of my soul?,” or “Girls gather in the alley and talk without moving their lips.” The reader can see, hear, and feel it, and the rhythm and pungency carry her along, as if she were in the blind tunnel at the amusement park. Though some images are of wreckage and despair, they’re still yummy. “I remain in the whirlwind and continue to be thrown away.”

Rachel Eliza Griffiths is another prose poet. Reading her work is like going to the spa; every touch, smell, warmth, and chill is palpable, meaningful, and healing. She addresses the pandemic in its atomic expression, taking us through the near death feelings when engulfed by a 103-degree fever. She shows us the virus from inside the body of a person suffering from it. She wonders, “Will I come through this if my body does not come with me?” She honors Tamisha, the forensic technician who places daffodils on body bags in the hospital morgue. In a bow to another aspect of our times, she remembers the Black lives lost. She steps back from the atomic in the end to comment, “The virus rears in sunlight, devouring bodies that will not mask, separate, isolate, listen. The virus is the arrow of the nation’s ego.”

A.Van Jordan’s poetry skims along accessible, meaningful. He encounters quarantined, sheltering people and “I ask them/and—is it possible, for the first time?—/I truly wanna know” echoing Meghan, Duchess of Sussex’s recent op ed that pleads with us to ask each other in this perilous time, “How are you?” Jordan picks and chooses his vocabulary and his allusions. He “hangs out,” talks of “swagger,” then he turns to Prospero, Caliban, Queen Elizabeth I, Shakespeare. His comparison of the words of Queen Elizabeth I and Donald Trump is a walloping riposte to those who dismiss racism and repression. Yes, this has been going on a for a long time. He quotes Langston Hughes, “I dream a world.” The juxtaposition of the high-fallutin’ with the everyday jolts the reader into acceptance of universality. Can’t keep this man down. “[.]..we continue long into night/into the coming day, a Soul Train of revolt/lining rural routes, and filling streets/in our cities with dance.”

Maggie Queeney writes “Inside the Patient is another Patient, perfect, and one/size smaller. Inside that Patient is another, and another,/perfect.” A poetic symphony of compassion for the suffering, the lost hopes, the destruction of what should have been. The patient is delivered “Into the hands of others, their palms slick with/alcohol or cloaked in latex in a blue chosen/for its quantified calming effect…” Queeney is writing what she knows, catching fragments of reality, of truth, and laying them on a silver platter for us.

She kneads the subject of “Patient” into many shapes, each enlightening, the words lovely and clear. “The Patient’s Book of Saints,” “The Patient has a History of Medical Treatment,” “The Narrative Arc of the Patient,” and so on. Not only does the situation of the Patient change, but the structure of her poems changes as she paints each with a different brush. If Queeney hasn’t been trained as a nurse, she sure feels like one, detail-oriented, caring, effective, sure.

Traci Brimhall & Brynn Saito are co-authors who sink into the senses, colors, and impressions of life, but yearn for certainty, for the power to protest. Theirs is a record of the isolation of the pandemic, but they also bring along the rising waters of climate change and the rife injustices that remain unaddressed. Ruin awaits. So what do you do?

Dusk summons me home with its sapphire curfew.

Do you want to know how I do it? I expect nothing.

And then, and then, the bright surprise of your arrival.

A poet cannot give up hope; it is her substance, her living. Who would bother to distill the essence of things if not to inspire others to rise above themselves and save us?

Denise Duhamel jumps right in: “I saw the best minds of my generation (i.e., Fauci, Birx)/Undermined by Trump….” This poem is titled “Howl,” a reference, perhaps an homage, to Allen Ginsberg. Just when you thought you’d heard the first draft of history told in every possible way, she comes up with a new way. She condenses the tiresome facts into an energy pill, then repeats: canceled doctors’ visits, essential workers, no visits to mom, masks. Duhamel pummels the reader again and again. “2020/always sounded to me like a sci fi year/but now it is here with a pandemic predicted/by both scientists and sci fi.” That doesn’t sound like poetry, but in Duhamel’s hands, it is. Here is our Samuel Pepys. Here’s the bam bam bam, and then bam, bam, bam, of indignity, sacrifice, loneliness, helplessness, the revitalization of Nature as everybody stays home, the lies, the needless death, the brutality—read on.

Rich Barot is the perfect final act, a series of effortless (lol, as if), funny, insightful, touching poem-paragraphs full of images, turns of phrase, palpable reality. Here is the last of them:

During the pandemic, I listened. Things hummed their tunes.

The pear. The black sneaker. The old-fashioned thermometer.

The stapler with the face of a general from Eastern Europe.

Once, my father confessed he had taken the padlock from his

Factory locker and clipped it on the rail of a footbridge at the

Park. He had retired. The park was near his house. Each time

He went there, I imagined him feeling pleased, going to work.

*

This review is but a tiny taste of a novel and enchanting work. Keep it at your bedside for a laugh, a tear, a thought, an inspiration.

A Review of Francesco Levato's Arsenal/Sin Documentos

Francesco Levato has created a disquieting and challenging book that provokes more questions than answers.

Francesco Levato has created a disquieting and challenging book that provokes more questions than answers. Reading the book pulled me into a dialogue with it, almost an argument, questioning it as much as it questioned me, challenging me as I challenged it. The book fits into no easy categories, and describes itself as “a work of poetry and concept art." This is an apt description.

The title, Arsenal/Sin Documentos, packs a lot of information about the book. It is nearly a complete summary. The slash cuts the title in two, apposing English with Spanish in a dialectic juxtaposition. Arsenal is an English/Spanish cognate, and according to the Merriam Webster Dictionary, it means “an establishment for the manufacture or storage of arms and military equipment.” The word can also refer to a store, repertoire, or set of resources without necessarily denoting weaponry; as for example, “she had developed an extraordinary arsenal of mathematical techniques.”

The right side of the title, the part following the slash, ‘Sin Documentos,’ is Spanish for ‘without documents.’ This seems an explicit denial of fact for the book is itself undeniably a document. Moreover, the book consists almost completely of official U.S. Government documents. So, the title, Arsenal / Sin Documentos, is a paradox that works simultaneously on multiple levels.

Sin, that prominent middle word has the joy of living in both languages, but with different meanings in each. Clearly, sin connects the left half English word directly with the right half Spanish one. Sin sits between them like a fulcrum, balancing the left and the right hand parts of the title in a kind of sour bilingual pun. The title connects documents, their absence, weapons, and sin.

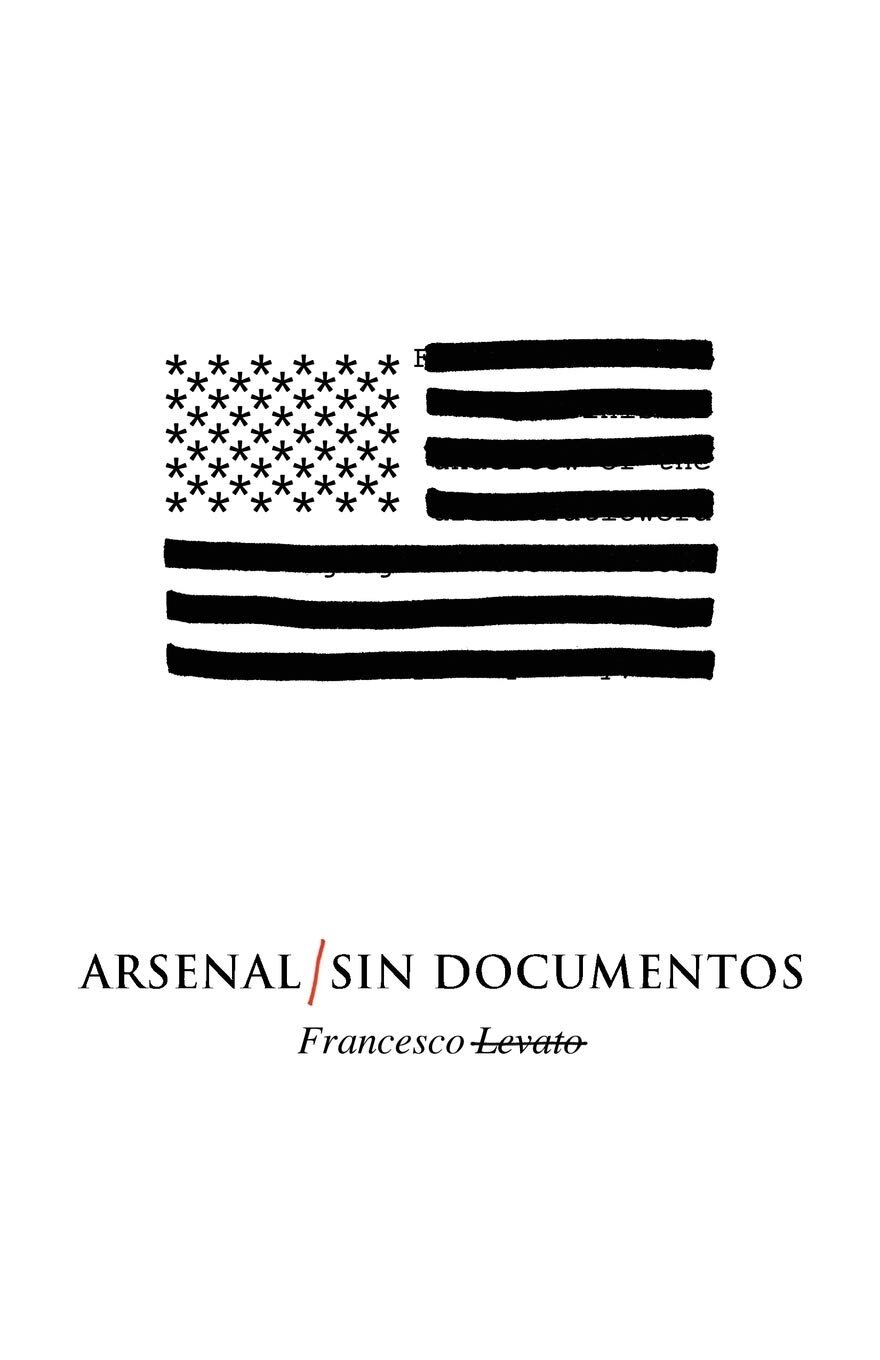

The cover of the book displays a couple of graphic elements that reflect the core of the book, its purpose and message. One of these graphic elements is the way the author’s name is printed. While the first name, Francesco, is in normal text, the family or surname is in bold font with a strikethrough; i.e., Levato. The visual impact of the strikethrough, featured on the cover, prominent under the title, is visually disturbing, bizarre, and absurd, which is consistent with both the core message of the book as well as the compositional techniques Levato uses.

Roughly about half the pages in the book contain text that, not only has a strikethrough, but been completely obliterated with a thick, heavy, black marker pen. On flipping through the book, the effect is undeniably eye catching and dramatic. These pages look as if an outraged state censor, intent on demonstrating his fury, worked these pages over. Page after page contains text that is completely unreadable. These are not polite, carefully executed erasures. These pages have been violently obliterated. The visual impression these pages communicate is the intentional destruction of the text; they are a visual embodiment of anger. They look like the product of an imperious totalitarian government. The anger works on two levels. One level is Levato’s own rage at the text of the government documents he obliterates. The other level is the subtext of emotion and affect contained in the original government documents themselves that provoke Levato’s rage. Notes at the end of the book state that the “. . . book consists of a series of linked documentary poems composed of appropriated language from U.S. government documents such as: Customs and Border Patrol handbooks, the Immigration and Nationality Act; the U.S. patent for Taser handheld stun guns,” and so forth.

Levato structured the book into fifteen parts, each part beginning with an untitled but numbered policy statement, ranging from Policy .01 through Policy .15. Each of these policy statements is followed by one, two, or three additional documents on a variety of topics, some in Spanish, some in English. This organization parodies the government documents and the bureaucracy that produces them. The book’s index displays the book’s general outline and organization, with the numbered policies, sections and subsections, definitions and so forth, mercilessly printed in a standard government format and font that is intentionally designed to minimize any sense of humanity and to discourage reading. Importantly, these documents form part of the government’s arsenal of regulations, policies, procedures, and other weaponry employed to secure our borders. The documents describe the specific levels of violence acceptable for the enforcement these policies; and in the process of enforcement, apprehending, harming, brutalizing, criminalizing, and if necessary, killing the alien morphed to victim/villain. Levato uses these texts as a canvas on which to expresses his rage at the text and what it embodies. Thus, the book is a collection of Levato’s passionate abstract expressionist sketches of anger and outrage reflected back onto the text that itself embodies anger and outrage. In this respect, the book is more a work of visual art than of linguist art.

The cover has still more to say about the book. A large portion of the cover is devoted to a black and white rendering of the American Flag. The fifty stars are fifty black asterisks. The flag’s thirteen horizontal strips, normally alternating red and white, are rendered in black and white, the black being another heavy black maker pen redaction, completely obliterating whatever is under it. Thus, the cover, with the strikethrough, the heavy blacked out redactions, and the reference to a caricatured nationalism of the flag, displays several main compositional elements of the book. These elements include the obvious fact that everything in the book is printed in black and white, not only on the page but also in its world view.

Not all of the pieces of the book are dramatically overwritten and blacked out. A much smaller number of documents appear so faintly on the page they are virtually impossible to read with the exception of a few words scattered here and there. These pages of faint text contrast with the black heavily marked out text that dominates the book. The faint, disappeared text reminds us not only of how privilege afforded to the wealthy is visibility while poverty is assigned invisibility; but also, the disappeared text calls to mind the disappeared. With these faint texts, Levato manages to evoke the disappeared, to call attention to those missing. He makes this move with great subtlety, so we pause and mourn.

This book has an absolute unity of purpose and singleness of vision. It realizes an overarching inspiration and design. It is by no means a collection of separate individual pieces; rather, it is a single unitary creation. The document’s appearance on the page, its physical embodiment contains, illustrates, and conveys its meaning. This 151 page book, in its entirety, is more like a passionately conceived, concrete poetic monograph than anything else. It is a convincing, deeply satisfying, compelling, yet emotionally disturbing document to spend time with. I have never encountered anything quite like it.

An Interview with Matthew Thorburn, author of The Grace of Distance

The poems in The Grace of Distance have to do with a variety of distances—between people, between cultures, between different physical places in the world, between faith and doubt—as well as the sense of perspective and understanding that can come with distance, whether it’s a matter of physical distance or time passing.

Marcene Gandolfo: I read The Grace of Distance in the summer of 2020, and your poems, which meditate so eloquently on the very nature of distance, spoke to me with a profound immediacy and relevance. Of course, I know that you composed these poems long before you knew of the impending pandemic or the social distancing that would ensue. Still, can you speak to the collection’s current relevance? From writing these poems, have you acquired insights that help you face challenges in these uncertain times?

Matthew Thorburn: Thank you for asking—that’s a very timely question, and something I’ve thought about too. The poems in The Grace of Distance have to do with a variety of distances—between people, between cultures, between different physical places in the world, between faith and doubt—as well as the sense of perspective and understanding that can come with distance, whether it’s a matter of physical distance or time passing. That’s what I was thinking about as I wrote these poems over quite a few years, and certainly when LSU Press published this book in August 2019.

But it is strange, isn’t it, to think about how the word “distance” has taken on such a different meaning this year? So many people are enduring all kinds of terrible hardships right now—whether it’s sickness, caring for a loved one who’s ill, financial hardships, loss of employment, or other personal difficulties. I can’t help thinking of distance in terms of the loved ones who I’m not able to see right now, such as my parents and aunts and uncles, as well as many friends. Spending time by yourself has its virtues and can lead to a kind of grace, I think—as a writer, or even as a reader, this seems especially true—but being separated from family and friends is a hard (though right now very necessary) thing to do.

However, I also know I am immensely lucky that my parents and other loved ones are healthy and doing okay, and I am very fortunate that I’m able to do my work from home. Spending most of this year working from home has meant much more time with my wife and son—the opposite of distance—which has been an unexpected gift. I try to keep that front and center in my mind and just take things day by day.

MG: Can you say something about your composition process? Do you write daily? Do you engage in writing rituals? In particular, what role did this process play in the construction of your book? In particular, how did the theme of distance emerge?

MT: Prior to the pandemic, I did most of my writing on mass transit, during my commute from my home in New Jersey to my office in New York City, and back. I also had a good routine of working on poems during my lunch hour. Each day I would carry printed copies of poems I was currently working on, and I’d mark these up with edits during those times. Then I’d type in my edits at home, print clean copies, and do it again the next day. Or if I was working on a manuscript, I’d carry a copy of that in my briefcase to reread and mark up. It might not sound ideal, but this writing practice worked very well for me. It’s how I wrote many of the poems in this book—and these days I sometimes daydream about my favorite spots in midtown Manhattan where I could sit outside to eat my lunch and work on my poems.

The Grace of Distance originated in a file folder where over the years I saved poems that didn’t make it into my previous books—mainly for thematic reasons—but that I thought were still very good poems and wanted to keep. (There were also a handful of shorter poems I’d written while working on my book-length poem, Dear Almost.) Eventually, as that folder grew thicker, I read through these poems again and came to see that they hadn’t fit into those other books because almost all of them were about something else—those different kinds of distances. Once I recognized that, I continued writing new poems with this theme in the back of my head.

MG: In “A Poem for My Birthday,” you write, “ . . . “Whatever happened / to longing, you ask, but I long for that / red barn town where I was born . . . ” As these poems continuously travel, do they unremittingly search for home, escape from it, or simultaneously do both?

MT: I think they probably do both. As someone who grew up in one place (the Midwest), then lived for nearly two decades in a very different place (New York City), and now lives in still another different-feeling place (small-town New Jersey), my sense of “home” is complicated. I find myself looking back to Michigan, as in the poem you quoted, as well as writing poems that are set in and focused on the landscape where I live now. When it comes down to it, if you said “home” to me I’d probably picture Lansing, Michigan, where I grew up—though I have to tell you, after nearly three years here in central New Jersey, I feel very much at home here too.

Having said that, though, I find that it often works best for me to be somewhere other than the place I’m writing about—to be looking back at where I’ve been, to have that distance. And certainly, as I get older, I find myself writing more about the past and childhood memories. This is probably why this theme of distances came so naturally to me—why I discovered I’d actually been writing poems about it for years!

MG: In the collection, several poems explore the role of art in bridging interpersonal distances between time and space. Could you elaborate your thoughts on this subject?

MT: I love writing poems about visual art, especially paintings, as well as about music. I’m really drawn to the stories that works of visual art can suggest. And it amazes me to stand in a museum and look up close at a painting and think about the fact that Vermeer once stood in a similar position and put this paint on this canvas. To me that suggests a distance that expands and contracts all at once. As I describe in my poem “Forgotten Until You Find It,” seeing the Girl with A Pearl Earring at the Frick Collection was a powerful experience for me.

In writing a poem I want to share something—to try to enable the reader to see what I’m seeing and feel what I’m feeling (even if those sights and feelings are ones I’ve imagined). I think it was Philip Larkin who said a poem is like a river you can step into in the same place again and again. There’s a sense of connection I feel in reading the poems I love best, or looking at paintings I love, and I hope I am able to create something like that in my poems too. Paintings are made to be seen, usually, just as poems are usually written with the intention that others will read and hear them—so I think that’s something we have in common.

MG: In a number of the poems, you speak of language in relation to space and travel. For instance, in the poem “No More,” you write “As though many little doors, slow to close, / are closing now: how the doctor speaks of her dying. / Stepping over the puddle of each period / the reader lets each sentence slip away . . . ” Could you comment on this metaphorical connection?

MT: Well, language is one of the main things that connects us, one of the ways we make connections with other people—and I see metaphors like those as not only elements of poetry, but also one of the ways we can understand complicated aspects of life—or in this case, of death. In “No More” I was writing about my grandmother, who had a stroke and lost the ability to communicate verbally. Over time she regained quite a bit of her speech but was never able to talk the way she once had. I think that’s a metaphor—those closing doors—that I came up with in thinking about her last days in hospice and how the human body can go through a process of shutting down. Turning off the lights in a house, room by room, is another way I pictured this, though that didn’t end up in the poem.

MG: What is next? Are you engaged in any new writing projects? If so, would you like to share a bit about your current work?

MT: Thanks for asking about this. Right now, I’m working on two projects I’m very excited about. The first is a book-length sequence of poems about a teenage boy’s experiences in a time of war and its aftermath. He loses his family, friends, virtually everything, but somehow survives to tell his story. This book is a real departure for me, stylistically, because the poems are written almost entirely without punctuation—except for a period at the end of each poem. “Go Together Come Apart,” my poem about Matisse’s collage “The Swimming Pool” in The Grace of Distance, is a preview of how this mode of writing works for me. For years I was resistant to poems without punctuation and didn’t like reading them. But then the experience of reading my friend Leslie Harrison’s amazing second collection of poems, The Book of Endings, completely changed my mind. Seeing what she did without punctuation—the possibilities that open up when you remove punctuation—inspired me to try writing this way. (You can read a couple of poems from this manuscript online here and here and here.)

The second project, which is still taking shape, is turning out to be a book of elegies—looking back to childhood, as I mentioned earlier, as well as trying to remember loved ones and hold onto memories of them in words. The manuscript is anchored by two sequences of poems—one about my grandmother, Majel Thorburn, and one about my mother-in-law, Fong Koo. This manuscript is also somewhat of a formal experiment. For years I’ve thought about trying to write more prose poems—and in fact quite a few of these poems are prose poems and Haibun. I’m still writing and revising these poems, so I’m excited to see how my imagining of this book will gradually come to life over the next few years. I find with each book it’s a little different, but always a process of discovering.

A Review of Lord Baltimore by Peter Ramos

There is little anger or recrimination within these pages, although you feel that at times it might have been justified; instead, what comes across is a benign maturity, a sort of kindness.

Poets all too often forget their responsibility to give the reader at least a chance of making sense of their work, or they choose to be deliberately opaque to disguise a lack of meaning, of purpose. Let us then give thanks for this fine collection by Peter Ramos, associate professor of English at Buffalo State College, which offers Intelligent, original and accessible poems that awaken the senses and reignite one’s enthusiasm for verse.

The book opens with a thoughtful little piece, dedicated to his children, about the end of a summer day; a day defined as “an open melon / thrumming with insects and minutes” which at night, inverted and reflected in the water, is “completely awake and truer than time.” There’s a lovely sense here of magnanimity in the heavens. It’s a gentle introduction to a series of poems which gather pace and vitality: qualities which are nowhere better expressed than in the title poem. In twenty-three parts and spread over sixteen pages, it is ambitious and various, never once flagging in interest or readability. It tells of a young man and his entirely unromantic existence as a would-be writer in the city of Baltimore.

In the first of numberless studios he has high expectations of high art and “green bohemian chatter”, with rusty industrial landscapes as the backdrop to his idealism. But the reality is somewhat different — the heat, the peeling plaster, the “accumulations of dandruff, the dead skin of decades” forcing him out to the street “with a gathering unbearable thirst”. Money is short, and he takes on dead-end jobs to pay the rent, such as painting a porch, or working at a sewage treatment plant where his boss has a steel rod in his back, and is afraid that a lightning strike might “solder my asshole shut.” He drinks too much; he dines on canned tuna and a six pack, and comes home to dust clumps and mice droppings, hearing his mother over the phone asking “in a tiny, wavering voice: are you okay?” He finds companionship and sex with a girl who could not love him — nor he her:

. . . both of us

sweating, furiously holding on

to each other in our twenties.

and goes on to consider:

How we shone in that place

then, freshly devirgined, stars pulsed and slow

to go out.

How pretty now when you blur your eyes:

green jewelry glittering down

black glass, crackling

as it fades to cinder, to shadow —

trash.

Beautiful. I could quote endlessly from this poem. It’s quite an achievement to depict someone alone, small and terrified and out of step with the world, with a combination of strong imagery, wit and honesty, and which asks for neither pity or approbation; which so thoroughly captures the life of one who could say:

Here’s to you, Lord Baltimore, not Poe. I’m yours

truly, sunk, un-publishable, a mere scribbler

bon vivant, my glasses cracked & knocked

askew. By noon, I’m just another

dipshit local drunk.

Such a sense of failure pervades the piece. At last, after questioning himself and his existence among the empty factories and “smokestacks, chemical sludge, the sunset bruised with propane” he decides he has had enough and:

I got out.

Walked for years, the flames

eating my skin

less and less, dumb and dazed,

afraid but steadying, toward no place

I’d ever known.

It’s a wonderful piece of work, seeded with lyrics from Harry Nilsson’s “Everybody’s Talkin,” to lend atmosphere, and snippets of historical fact about Cecil Calvert, the second Lord Baltimore, to add perspective and contrast. It is most unusual, in my experience at least, to come across a poem that is quite so thoroughly engaging.

But there is so much more to admire here; so much variety and energy and colour: from a lyrical, if discretely troubling hike in Virginia without books or medicine, watches or spirits:

just musical gnat-clouds

over the brook, the light-dazzle

on water’s skin

and wet pebbles

to an anecdotal piece on teenage rebellion and bravura summed up in a hundred fizzing words. From a pool-side scene in Hawaii featuring women in almost nothing but anklets, lipstick and nail polish who are, and have always been, wholly out of reach, to the simmering discontent of a group of working-class men on a hot fourth of July. Accessible maybe, but these poems lack nothing in depth or meaning, and have that rarest of qualities — they merit further visits.

There’s a solidity of detail within these poems; an absence of obscurity or blind alleys. A Firebird takes the place of an abstract noun, a Flying V for an adverb. You’ll find Catholic iconography and ranch houses; high-jinx and hangovers; mildew blooming in the bathroom and astronomical fire. This sort of construction, this directness, can sometimes be far more efficient in summoning a memory or evoking an emotion than a more reticent, a more delicate approach; and that, after all, is what being a poet is all about. This is not to say there isn’t subtlety here — there is allusion and metaphor aplenty — but there is also real content; something to get your teeth into. Who is not taken by a description of American mothers as “sewn up & impersonal, lost in daytime cable”, or a night of love in a jacked-up GTO by a dumpster, after which “Morning wiped out the stars & seagulls cried like bats”; who cannot empathise with someone who, in a boozy, down-beat moment sees the horizon peeling open with “phony billboards” featuring “faded cars, bad lawyers & disconnected numbers”?

I found a quieter poem, but no less effective, in “Viewing”. It’s the contemplation by a neighbour of a retired schoolteacher, husband and father of two, lying in a casket — “more wax / more chemicals than human meat” — alongside photographs of him attending communion, playing golf, the saxophone, tennis. Where, he wonders, is all that history now? They would meet occasionally taking out the trash:

in the starlight – diamond

crumbs on a backcloth — to stop

with a friendly word.

We weren’t especially close.

It’s a fine poem, if a little incongruous in its sobriety in this thrilling, inventive and affecting collection presented with a sure touch and a refreshing vocabulary. The dominant tone here is one of nostalgia; a fond recollection of adolescent spirit, tempered by misdeeds and embarrassment, with questions about identity and belonging posed along the way. There is little anger or recrimination within these pages, although you feel that at times it might have been justified; instead, what comes across is a benign maturity, a sort of kindness. When poetry is so often dry, or heavy-going or, worst of all, cloyingly self-indulgent, these verses are nothing less than a surprise. Like finding buddleia breaking through the sidewalk.

An Ouroboros, A Ceiling Crack, A Celestial Scale: A Review of Anna Maria Hong’s Fablesque

Fablesque [… speaks] the language of the unspeakable by bending folklore to the speaker’s needs to confront the Korean diaspora and beyond. These poems see things as they are, not as we’ve been fooled by the legends of our forefathers to believe that they are.

One of my first writing instructors told an early workshop of mine that every time he read a particularly good story or novel, his first thought was damn, I should’ve thought of that first. I’d be lying if I said I didn’t feel that same sense of envy sometimes, as I wade through and untangle the genius, generous, boundary-pushing work of my peers and idols alike. Sometimes it’s impossible not to watch some brilliance unfold on a page in front of me and wish I had used some part of it in my own work. Other times I’m driven to pick up the pen myself and start falling down my own lines of inquiry, branching away from the inspiring material I’ve just read.

My experience reading Anna Maria Hong’s Fablesque, winner of the prestigious 2017 Berkshire Prize for a First or Second Book of Poetry, was entirely different, starting with the first lines of the first poem of the book. Immediately, upon turning through its first few pages, I recognized Fablesque as a cunning, yet untamable beast, a protean pinnacle of hybridity, courage, and wit, a text, I believe, that could only come from the mind of Hong, its creator. To me, this is the highest form of poetry, when a poet’s found a voice so uniquely their own that the power it wields seems as if it could shatter whole worlds only to bind them back together with song.

I would not hope to imitate or even try to replicate what Hong has done in Fablesque, how she balances lived experiences with the reclaiming of myth, how she moves so effortlessly from the high lyric to the narrative, to the historical, to the autobiographical. And, while it’s true that hybrid texts have been in vogue for the past few years or so now, I’ve never seen a book use its hybridity quite so deftly, so seamlessly as it’s used in Fablesque.

But Fablesque has tied itself more closely to folklore and storytelling than it has to hybridity; while many of the poems in the collection don’t directly blur genre, the majority of them engage with folklore, whether the speakers orients themselves within these poems by aligning with starving wolves, diving through the history of windows and fish ladders, or retelling sometimes familiar stories with a biting newness.

Fablesque hits the ground running with “Heliconius Melpomene,” named after the postman butterfly, which is remarkable for its ability to evolve rapidly, having become the subject of extensive study on speciation and hybridization in butterflies. “Heliconius Melpomene” starts with a fractured high lyric: “Not the branch but the dismantling. If// I could have seen the shape of it,// I wouldn’t have made the journey,” the speaker recalls before pouncing from image to image, landing on “venom in a bloodstream.” The next lines make a quick turn toward remembering the speaker’s father’s escape from North Korean soldiers at the beginning of the Korean War with the detached narration and high stakes of a fairytale: the father’s two companions, we’re told, are shot in the head, but the speaker’s father survives through an act of cunning. The poem bobs and weaves again, turning to the perspective of the speaker at thirteen: “My middle-aged father’s smooth, blankly animated face telling the parable of his own cunning and lack of disabling empathy.”

Fablesque works this way as a whole, flitting between subject to subject, speaking the language of the unspeakable by bending folklore to the speaker’s needs to confront the Korean diaspora and beyond. These poems see things as they are, not as we’ve been fooled by the legends of our forefathers to believe that they are. I’m particularly struck by the language in the prose poem “Wolf: “The wolf was entrapped by its cravings—not for the Woodcutter with whom she has no quarrel or interest but for the Woodcutter’s beasts; his chickens, hit goats, his sheep, the animals of restive living” before continuing “But the Wolf is not picky. If the Woodcutter had kept monkeys, cockatiels, or Schnauzers, the Wolf would have pursued them too” later on. Not only do we see a desperate wolf caught in a trap, but we feel her hunger, her cravings. We see ourselves in her voracious thirst.

This, I believe, is where Fablesque succeeds most: bending folklore and convention to reimagine trauma, to recontextualize real-world suffering into fable and breathe life into the world of fairytale so that it, too, can speak to living in the world today.

Poems like “Siren,” which give voice to an often-maligned creature like the siren, also strike me as particularly interesting. The first few lines are spellbinding:

“When they turned me into a bird, they

turned me into a woman,

my top half full of breasts and throat,

the bottom all claw and dirty venom.”

Not only does this poem bring sympathy to the siren (which is traditionally known for luring sailors out to sea with their song only to devour them after they drown), but it gives us her origin, her twisted body, her dirge of fate. Later lines bring humor and sympathy into the present day:

“Goals for a Monday:

—rip out the knees of the patriarchy

—practice histrionic but alluring singing

—do laundry”

And while I can’t help but find humor in the “do laundry” note at the end, the other two goals strike me as human while also doubling down on that the idea of the siren comes from a historical, patriarchal demonizing of women and their sexualities.

Many dramatic moments of Fablesque are also informed by the parataxic hybridity created by placing certain poems side-by-side, as in, say the abrupt, high lyric of “Kronos” with the fairytale-like “Snow Goose” and the more narrative “Blue Morpho.” Fablesque is a collection full of tension, but it’s a tension that fuels innovation and encourages exploration for speaker and reader alike.

Some poems, like “Patisserie du Monde” are playful; some, like “HK Rules the Planet,” are puzzling; and others, still, are full of linguistic joy, as in “Amphisbaena: “The amphisbaena has no natural predators, being/ unnatural. Lust overlaps chastity,// bronze scales on a sealed ring.” Other poems interrogate ceiling cracks, basement wall cracks, wandering chambers, stairwells, and any number of spaces between.

After all, the work in Fablesque capitalizes on the greatest power of myth: It isn’t real, but it speaks to reality. Fables aren’t true, but they speak to truth, and, in doing so, they create a liminal space for brilliant poets like Anna Maria Hong to reclaim myth from its patriarchal past and appropriate it for their own ends. Each time I read Fablesque, I find new moments of wonder, new amusements in this carnival of language to comfort me and discomfort me, to intrigue and unsettle.

At face value, a poem like “Nude Palette” might read as frivolous with its opening line of “What a muse, what a mess, this state of undress,” though it quickly turns our attention to Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 with its continuing lines of “descending the spiral stare—to look back is/ to profess, resume the harness, and lose/ the myth of progress.” These lines, along with the rest of the poem, are enchanting, but they also have something very real to say about the treatment and placement of women in modernity and other parts of the contemporary landscape.

Fablesque is full of what an old mentor of mine would call “poetic fun,” but it’s also full of depth, intrigue, and commentary about the worlds around us, both real and imagined. As one might expect, there’s more wonder and more cunning in even a fraction of Fablesque than I could ever dream of including in this review, but I consider myself lucky for having had the chance to explore its geographies and dreamscapes, its intrepid spirit, its fearless takes on vicious beasts, astral bodies, and ancient gods alike. Any reader who gives themself the chance to fall in love with Hong’s work will find themselves grateful the same way.

The Multiple Deaths of Living: Reading Victoria Chang’s Obit

Chang reminds us that our willingness to explore the darkness of our own grief can nurture our attentiveness to the grief that occurs in other parts of the world. Our personal grief is inevitably bound to collective grief, and both types of grief are worthy of belonging in the same sentence.

If I were to say, “My friend is experiencing deep grief right now,” I suspect that most people would assume that my friend is in grief because of the death of a loved one. However, the understanding of “grief” in the collective conscience — especially since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 — has rightfully expanded so that grief includes the loss of varying life circumstances. We grieve that we longer believe in the faith tradition we had practiced since childhood. We grieve after realizing our spouse isn’t the person we had believed them to be and we can’t save the marriage. We grieve over not being able to attend in-person classes without the constant worry of potentially spreading COVID. We grieve that our current lives don’t reflect the hopes and dreams we once had for ourselves.

“The art of losing isn’t hard to master,” as Elizabeth Bishop famously remarked in her beloved villanelle “One Art.”

In April 2020, amidst the start of worldwide safer-at-home orders, Obit by Victoria Chang was released. The poems in this collection were written after her mother died of pulmonary fibrosis on August 3, 2015. Instead of opting for the traditional form of the elegy to explore her grief, in her poems, Chang chooses to engage in hermit crab writing by using the one long and skinny rectangle form of obituaries to inspect the multitude of deaths that unfurl in a human life. Though she does write about the literal death of her mother, she also writes about how her mother’s teeth metaphorically died after being pulled out. Other deaths that she writes about include her own ambition, optimism, and friendships. Interspersed in the book are tankas that Chang writes her children about subjects like death, hope, and love. In addition to obits and tankas, a lyrical poem spread over several pages is a part of the collection.

Grief is an inextricable part of our human existence. Though the specificities of individuals’ experiences with loss may differ, every human being will go through some sort of significant loss (should they live for enough years to eventually go through it). Just as universal as grief is, the need to have one’s grief be attended to is as common. I have acutely witnessed a multitude of metaphorical deaths and a literal death throughout my life, and I always felt that not even attempting to verbalize the ramification of those losses would eventually result in overwhelming agony. The first epigraph in Obit is “Give sorrow words; the grief that does not speak wispers the o’er-fraught heart, and bids it break,” from William Shakespeare’s Macbeth. After that epigraph, Chang goes on to share 81 heartrending obits. Considering how many people prefer not to talk about their grief, the wisdom in the Shakespeare quote and the high number of obits in this book make me believe that most people don’t talk about grief as much as they should in order to find some healing, and there are perils in denying and avoiding the deep pain that follows a loss.

While I intellectually know the psychological benefits of speaking about loss and grief, I do recognize that speaking about loss and grief is really hard. As I examine the poems I’ve written over the past two and a half years, it has only been within the past year that I’ve mustered the courage to transmit the emotions of my grief experiences into poetry. I also noticed that, like most of the poems I write, those poems about grief were written in a free verse lyrical style. Writing more poems about painful experiences, such as grief, is an important goal of mine, and I am fascinated by the forms that Chang uses to write about her mourning. The obit poems are not only in hermit crab forms, but they’re also prose poems, which is a form that I’m easing myself into also practicing. The tankas that Chang writes also captivate me because they’re only five lines with a total of 31 syllables, yet they are filled with rich images infused in profound statements like “I tell my children / that hope is like a blue skirt, / it can twirl and twirl, / that men like to open it, / take it apart, and wound it.” As a lyrically-inclined writer, my writing can come off as rambling, and I’m gleaning from her effective directness.

Though most of Obit addresses the losses that she undergoes in her personal life, Chang ends the book with an obit that addresses shootings in Florida, particularly at Stoneman Douglas High School. This obit also addresses her mother as it begins with “America-died on February 14, 2018, / and my dead mother doesn’t know. Since her death, America has died a / series of small deaths, each one less / precise than the next.”

I’m so appreciative that, by addressing the deaths from shootings and the death of her mother in the same sentence, Chang reminds us that our willingness to explore the darkness of our own grief can nurture our attentiveness to the grief that occurs in other parts of the world. Our personal grief is inevitably bound to collective grief, and both types of grief are worthy of belonging in the same sentence.

Like Victoria Chang and many fellow writers, I like to write about dark topics such as suffering and sociopolitical matters. I’ve never tried to write about my personal grief and sociopolitical events within the same poem, but I’m inspired to give that more of a try, especially as I become more keen on contributing to the creation of more peace in this chaotic world while simultaneously accepting the wildness of my heart and making peace with it.

As I read Obit and as I push my way through completing this essay, I struggle with the question of “What’s the point?” as the COVID-19 pandemic worsens and 2020 continues to serve one traumatic event after another.

I suppose it’s worth giving words to those feelings,

the grief.