Too Restless to Conclude: A Review of CHALK SONG by Gale Batchelder, Susan Berger-Jones, and Judson Evans

Their voices appear to emerge from the cave itself , telling a forgotten history that suggests Plato’s cave along with the obscure borders of personal memory.

Traditionally the ekphrastic poem pairs a single still image with a text, creating a tension between the spatial characteristics of the image and the temporal movement of the poem. The poem may perform a variety of functions, explaining, extrapolating, interpreting and setting the image into motion. It can unravel an allegory or develop a narrative that leads up to or completes the frozen moment of the icon.

In Chalk Song, Judson Evans, Gale Batchelder and Susan Berger-Jones apply the tradition to Werner Herzog’s film Cave of Forgotten Dreams, a documentary about the Chauvet Cave in Southern France, the oldest site of Cave Art in Europe, a place where art history begins in the shadow of an inhuman geology that both inspires and guides its formation. Their voices appear to emerge from the cave itself, telling a forgotten history that suggests Plato’s cave along with the obscure borders of personal memory.

By appealing to the film the three poets begin with an already moving image, complicating the image/text relation by essentially working beside the film echoing its concerns and animating the cave images themselves. In Chalk Song, everything moves, the text and its immediate referent, leaving no resting place for a definitive interpretation. The poems, while pointing back to the film and echoing each other, refuse resolution, too restless to conclude. The sequence further complicates the ekphrastic framework by appealing to an artwork that itself explores an earlier artwork. The poems then confront a site that has already been cinematically interpreted. Refusing to treat the film as a transparent representation, the poets acknowledge it as another interpretation, another voice in a sometimes cacophonic chorus of voices.

The cave represents a site of origins: of art , of technology, of humanity itself. “The altar was the first machine” writes Evans in a metaphor that sees magic as an early form of technology. Tellingly a recurring analogy in the film sees the cave as a proto cinema, a silent film animated by moving flashlights and headlamps. One expert describes the cave art as a message transmitted from the past to the present and posits the cave drawings as the origin of figuration and a prefiguration of film. The poems follow up on this assertion. Susan Berger-Jones refers to “the way errata blooms/sputtered through silent films”(57). Elsewhere, the shaman in Evans’ “Sediments”, gives way to a “flickering projectionist” an image that neatly conflates projector and projection, art and artist, both of which are obscured by the passage of eons.

Yet the shaman/projectionist remains a palpable absence in the cave’s imagery with its by depictions of animals ranging from horses, ibex, elks, wolves, and hyenas to birds, insects and butterflies. The single exception is a minitour like creature with the body of a bison and the head of a woman. As a scene of origins and emergence, the cave becomes a womb that asserts a commonality with the world of creatures even as it depicts an incipient differentiation between human and animal, nature and art.

The time that haunts the sequence is both the time of projection and the longer durations of history and deep time. In a startling surreal image in Berger-Jones’ “Hunted Circus, “a child is torn from her daguerreotype” and “fields are strewn… with charcoal horses,” a juxtaposition that collapses the history of image-making, as it leaps from the nineteenth century back to the stone age. Elsewhere the poets variously point to more mundane items of the twentieth century as disparate as Polaroids, radios and the internet, all of which hark back to the red hands on the cave walls as marks of ritual and human making.

While inevitably selective, the poems address the full range of the film’s images and information and in the process its interpreters. Gale Batchelder catalogs a number of talking heads zeroing in on their idiosyncratic histories; a circus worker who becomes an archeologist, a perfumier who locates caves by smell, a man who demonstrates archaic weapons. Each is a shaman of sorts sounding of the cave and its history for further information and nuance.

In spite of the myriad voices there’s a sense of continuing enigma, of the impossibility of the full knowledge of origins, of a complete return. Like the bison woman, “you can’t draw yourself out of the rock” and its mystery. “The footprints collapse into deeper footprints” writes Evans. What’s left is a sense of language echoing and, like torches, playing over the surface of a cavern that invites speculation yet keeps its secrets.

Echoes of Duality: A Review of Brandon Rushton’s THE AIR IN THE AIR BEHIND IT

While Rushton gives name and shape to seemingly minuscule commonplace daily activities, one has to also be ready to navigate the unfamiliar contrasting territories that are somehow both beautiful and frightening.

Even the cover of Brandon Rushton’s, The Air in the Air Behind It, is an invitation to consider echoes and reverberations, the shadow lives that reside in one’s daily existence. Rushton’s lines and descriptions are at once equal parts familiar and surreal. In his proem, “Milankovitch Cycles,” the setting can simultaneously contain mundane routines like calling children in for dinner, set apart by an unlikely event such as “a meteor cuts through the low cloud-cover and all the stampeding herds abruptly stop…” While Rushton gives name and shape to seemingly minuscule commonplace daily activities, one has to also be ready to navigate the unfamiliar contrasting territories that are somehow both beautiful and frightening.

The landscapes within this work evoke stark contrasts and counterpoints for consideration. How can peaceful evening routines be tinged with dread, fear, melancholy, and doom? “Family members joined at a dinner table/bless the food, made/of chemicals bound to break their bodies/down.” Each poem begins with normalcy perhaps “kids kickstanding their bikes,” or a bus in a city “that smells and sounds just like a bus/in every other city.” There is a sense of comfort while navigating these scenes, however, these images and places quickly shapeshift to reveal poems that grapple with climate change, the end of the world, the role of the media, and how everyone’s very lives are held at the mercy of capitalistic goals and metrics. These end times feel closer than ever when visited in Rushton’s verses, well within the readers’ grasp of turning pages or the passing of another year.

Somehow Rushton likewise makes his readers certain that they aren’t the victims here and are complicit in the damages inflicted upon one another and the world. Rushton asserts “No one has enough/guts to do the good thing,” while lines later he goes on “It is so appropriately us, sizing up an abandoned/house from the street, deciding whether or not/to credit card the door lock and take a look around.” People can place blame and critique the actions of others all they want, but Rushton reminds them that no one is completely innocent in this lifetime.

Lest one think that Rushton’s work is one of indictment or preaching pithy lessons for how humans can live better, and do better; this book is a far cry from that summation. He masterfully culls together structured poems with three-line stanzas that ground, reorient, and release the tension. “The season smelled/like orchard work and you/in a dress time won’t allow me/to describe.” But he doesn’t leave anyone there for long and in fact, moves to “This place that hardly/now exists. I take a photograph/to memorialize the view. I shake it still./It is the shaking not the stillness/that persists.” Even in the calmest lines, Rushton continuously pulls the orderly rug out from under his reader, keeping them cascading into skinny short lined poems, or losing themselves in sprawling prose poems. They’re never quite sure whether they will return to a peaceful suburban town or one that makes them consider the collapse of the economy or fish washing up on a local shore. And in doing this, the reader is forced to embrace the beauty that can exist alongside the acceptance of their own eventual collapse and demise.

Rushton’s poems each connect to the next, line by line and page by page, filled with riddles of striking images to unpack and later revisit. This is a book that needs multiple readings to discover and digest all that Rushton shares. At first, a poem’s darker theme and tone stand out, but then subsequent readings reveal the work's lighter gauzy words and layers. Rushton is an expert of enjambment with dizzying turns of phrase and nuance that is concurrently succinct and poignant, yet feels effortless on the part of the poet. Whether he is exploring the dual meanings of phrases and couplings, like “puddle jumper,” or delving into the “private life is on the public train,” all will delight in savoring each one. His book is proof that when everything else is stripped away, stories are all that remain as “time/has trouble keeping up/it lengthens and then retracts.” “The wake splits behind/and then apart a lot like leaving.” The natural world and daily living are tenuous at best, but lucky enough for Rushton’s readers, The Air in the Air Behind It will be there to shepherd them through the chaos of the world.

An Ode to Lava, in the Voice of Lava: A Review of Katy Didden's ORE CHOIR, THE LAVA ON ICELAND

Layering source text, poetry, and photographic fragments of the Icelandic landscape, the images give testimony to the earth's predilection for breakage and change. Word and letter islands erupt as patterns over a landscape, only partially revealed.

Ore Choir sings an ode to Lava, in the voice of Lava. Yet, like Whitman's song these visual erasure poems belong to all creation. God-like in the power to destroy and create, Lava makes land that resembles the life of humans and their spiritual yearnings: "Here a soul found the origin / desire / under all things...." It is the soul and desire of rock that resounds, sung now and long after human life is gone from the planet. Lava shares our mortal fear: " I still blanche at the void. / The answer is, / again and again, / to erase the ground."

Layering source text, poetry, and photographic fragments of the Icelandic landscape, the images give testimony to the earth's predilection for breakage and change. Word and letter islands erupt as patterns over a landscape, only partially revealed. The volatile topography crinkles, heaves, and vanishes under the poems, the images resembling rodent-nibbled pages of an illuminated manuscript. Precise photographic detail defers to the sweep and gesture of graphic art, the texture often blurred by text, smoke, and steam, to nuanced effect.

The front cover shows a detail from the last image, speaking to nonlinear time. Words scatter or congeal to soften the impenetrable material of stone. This is work the book takes on—uncovering sentiment-free tenderness in what might appear to be only the violence of volcanoes and the hardness of rocks. " In love, / beyond these stones, / like water, / I rise." Land erased by lava, and lava, reimagine themselves, a phantasmagoria at once gleaming and terrifying: "Lava IS the dragon. / I clot the sky with gold."

A fainter pulse of the human in a dynamic universe suggests heavenly calm, glimpsed through the rain of lava and color washes of Iceland. Lava wields wisdom of geological and mystical realms: "I add land / and undo the maps. / Leaders stride / across trackless paths, / following the turning law back to the source." The poems flow with the internal logic of Lava as set forth in the book. Lyric time is deep time. Beginning at the center: "Art is central— / sun and stone. / I trace the beginning / of the modern; / I paint vales."

Thwarting the brain's expectation for saturated colors—specifically red and orange, the fiery reality of lava—the book offers photographs rendered in muted earth tones, (also gray blues and greens). Only occasionally does rock flush with the color of a drying wound. The poems mention the word 'red' only briefly. This strategy allows the reader to perceive Lava as pure force and being, rupturing and covering what exists in order to make it new. What is left unsaid, and what is omitted from the spectrum, the reader creates as afterimage. On the page, Lava throbs with white heat.

The Völva, the Priest, and the Scientist join the choir with questions. Answering the voice of the Scientist, Lava says: "I unmake eternity, / rewild gold, / fluent as the migratory birds / that reverse the ground." The Scientist asks: "What was fixed? What was fluid?" Lava's answer: "Lobes crept in hollows. Birds fled." These are questions we can ask about permanence and erasure, addressing the meaning of absence—the making and unmaking of a country, planet, or a self. When the priest asks Lava, after a great volcanic disaster and miracle: "How do I pray now?" Lava answers: "Nothing lasts. Bless that." This makes sense in deep time, and signals the inevitable return of earth to a place without humans. The questions arise: Is there light in this? Shall we mourn?

Ore formed, as a wish to: "know poetry..." and "... (ran) to put an end to war." War and poetry rear up like newly formed mountains in this chronicled metamorphosis. Geologically there are no surprises, because everything is a surprise. Capitalism gets its own succinct page—a blip in time, eternal consequence: "Capitalism co-opts ore, air, water, hour, epic." The elements join the ephemeral hour. Nothing is spared.

The final question of the book is the Scientist's: " What lingers? This invites us on a journey into the ore of possibility, and to seek human company in the face of climate change and suffering. In the voice of Lava: "Will you lean on each other / when I wreck the seasons?"

The relatively shallow space of the visual poems, despite streaks of distant vistas, creates an intimate space for the reader. This is, paradoxically, the perfect space for the eye-of- god vastness of the subject. At the edge of each image, a nomadic coastline is suggested, impossible to measure.

It is worth mentioning some of the compelling source texts that shimmer behind the upheavals, sometimes creating their own fire. They range from a Siggi's yogurt label to a Historical Dictionary of Iceland. A recipe for volcano bread makes a cheerful appearance. Benjamin Franklin, W. H. Auden, Jules Verne, and John Ashbery among others, speak from behind and formulate new meanings, interlaced with the lava fields. In this realm of restlessness, Lava is master.

Observant Eye: A Review of Stelios Mormoris’s THE OCULUS

The idea of a “compound eye” is very much a part of Mormoris’ vision. Joys and sorrows intertwine in this collection and Mormoris illuminates them with his observant eye.

The title of Stelios Mormoris’s The Oculus is based on his background in architecture and his fascination with the “round or oval opening, small rounded window, with or without a glass panel, which is generally located at the top of a dome.” His attention has long been drawn to examples of oculi in architecture, but he emphasizes that none of these has “more significance than the oculus of the eye.”

What the poet doesn’t mention is another definition of oculus, namely the botanical and zoological definition: “an eye, spec. the compound eye of an insect.” The idea of a “compound eye” is very much part of Mormoris’ vision.

The first poem, “Return of Icarus,” a persona prose poem, establishes the first lens of the oculus, the Icarus who didn’t just fail, but “set out” to fail, gifted “with wings of wax and feathers, every child’s sleeping and waking dream.” Rooted to the world with his “arsenal,” his choice was clear. He “flew straight into sky’s pandemonium,” listening to the sea below him and the sun above him.

This Icarus is drawn to the oculus of the high dome, but he sees with the oculus of the compound eye.

Icarus returns out of love and finds “the color of murder,” his lapsed friends, his cat, his father sleeping, each a visual detail, the cat “purring in a stand of reeds,” the father “sleeping with his hands on his face.”

Yet, there is a voice from above that wants Icarus to return, the voice that “was heaven’s blame in cloud-shredded rays.” Icarus, the I, is “back in the aegis,” he is “sheltered from sun,” and his home is “an eye a marrow of light, my oculus.”

Having established his perspective, the poet offers three sections of work: Sentries, Aureoles, and Verdicts. From a compound eye, Sentries explores facets of a love relationship, Aureoles views many places in the world, and Verdicts explores his relationship with and observations of his mother.

In Sentries, “Mimosa” begins with “You cut me,” immediately clarifying the depth of the relationship. The poet takes the reader through detailed images like “you were a bubble of air / rising in a water glass” and “you lifted my limp fingers / like unwatered stems,” to the point where the you,

took me by the hand into the garden

to stand before the greening lawn

as if it were a well

and said my name.

“The Fog” is past and present. “The fog becomes memory of fog…” and the “I” is “not exactly lost but in fear of being lost,” driving in the fog, holding “to the white neon dashes of the road.” There are images of descent, literal and figurative: “abysses everywhere that invited descent,” “shifted down for my safety,” and “lie down / at the nadir in a field of moss,” all of which rise to the final line, “I was in love.”

In the remaining poems of this section, many reference physical love, but all are detailed, imagistic, and linguistically original: “Poseidon’s spears spar,” “The insistent plea / that ‘love will end the madness’ / slithered inside me all day,” “the prized butterfly quivering // in a field of torn milkweed,” or the extended metaphor of trying to restore the “flung cup”,

white tips of light,

blue enamel lips of porcelain,

and the handle like a lost ear

falling forever.

In Aureoles, circles of light that surround something, especially as depicted in art around the head or body of a person represented as holy, the poet turns his eye on aureoles around the globe. He begins in Spain with “Corrida.” The poem snakes down the page as the poet recounts a bullfight interspersed with the observer’s comments, the “The false threat of the bull” that “looms like a cloud lowering,” the “silk’s scarlet red…catching my foreigner’s conscience / as a parody of blood and lapsed royalty,” the “dark maroon rivulets,” the cape slipping “to the ground like a dinner napkin.”

Whether in Paris, where tourists are “grazing on the excess grandeur of gargoyled boulevards,” or in San Francisco, where the poet remembers 1963 when he “straddled a pair of gleaming silver tracks,” waiting for a trolley, or in Oyster Bay, where the “tethered dinghy stirs, awakens, and makes a slow, circumspect circle like a clue,” each aureole has its own special time and place. In Kaiki Beach, he reminds us that even as there are circles of light, there is also darkness. The seafoam is like “torn lingerie,” and “a priest in a swath of black robe… gives his blessing to the unborn baby,” but this is followed immediately by “and, here, a coiled snake readies its strike in the tide’s aqua shallows.”

The third section, Verdicts, focuses on his mother. In this strong section, images of details sing and bring the mother to life. He begins with Barley, “barley crammed into thick honey laced with thyme.” Two thirds of the way through the poem,

she was dead

while we ate in the pew

together, children again,

and the reader, through the three word “she was dead,” is plunged with the poet into grief.

In “At Midnight,” the “mother’s thin hands” pull the plug on the Christmas tree lights which “froze into a filigreed silhouette of needles.” The poet waits for hunger to pass, for snow “to fall in the glass globe’s lens,” and to “bury my father / toppled like a log beside his dogs.” The juxtaposition of basic hunger, the small detail of the globe, and the enormity of burying a father heighten the large and the small.

In “The Apron,” the poet puts on his mother’s apron, shocked to find it

…hanging

on a nail, slump-shouldered,

as if she had just slipped out

in a rush to die.

So many details offer the reader a different perspective. In “Lord & Taylor,” the poet looks down to see “

…the delta of veins,

crepe skin over knuckles linked

like vertebrae, your wedding band gone…

then concludes “I knew you were broke.” This slant approach to the fact gives the fact potency.

Later in the section, he gives us his mother’s earlier years, first in “Margarita,” when the poet watches his mother put her “face on to face the morning,” then in “Mass in Harlem,” where he goes “straight to mass in Harlem,” where his mother was born. In “The Consommé,” he reminds the reader that

There will always

be spices in the spice

rack I can smell,

that refuse to perish,

reminding the reader that as long as he remembers her, blessed by the words “agapi mou,” she will have a form of eternity.

The poet dedicates his work to Margaret Zitis Mormoris with a quote from Kahlil Gibran: “We choose our joys and sorrows long before we experience them.”

Joys and sorrows intertwine in this collection and Mormoris illuminates them with his observant eye.

How It Began Before It Ended: An Excerpt from WITHOUT SAINTS by Christopher Locke

Without Saints is a breathtaking journey to rediscover hope between the ruins: Poet Christopher Locke was baptized by Pentecostals, absolved by punk rock, and nearly consumed by narcotics. Like Denis Johnson’s propulsive Jesus’ Son, Without Saints is a brief, muscular ride into the heart of American desolation, and the love one finds waiting for them instead.

It was two a.m. The Jetta was parked at the curb and I sat in passenger seat, top down. I felt vulnerable in the dark, uneasy with the city’s brick tenements and low sound. Directly overhead, a streetlight flickered like a dying brain. It was humid and I was dressed in shorts, a black t-shirt. I thought about my wife and daughter asleep back home and shifted my weight; my thighs stuck to the leather seats.

I replayed the evening in my head: After dinner, I finished grading my students’ papers on Thoreau’s theory of needs vs. wants and reread five pages of Marquez’s 100 Years of Solitude for another class. I changed Grace’s diaper and handed her off to Lisa, kissing them both and saying I’d be back by 11:00 at the latest. I went to my car, did four bumps of coke off the house key, and squeezed my eyes shut until the stinging passed.

When I arrived at a party in town, I had some whiskey, a little more coke, and then another whiskey. A white kid with dreadlocks got angry because all the tiki torches outside made the lawn resemble a landing strip, burning a symmetrical pattern that made him furious somehow. He pulled them out of the ground, one at a time, and threw them sputtering into the pool. A glass table followed.

That’s when Billy showed up. And what we wanted was only twelve minutes away. We would look for Psychs again. My heart raced. On the way, we drank beer from red plastic cups and talked about our students; we worked at the same school. The latest batch of kids seemed more docile, Billy said. I mentioned how much I liked the new boy from Jersey and all his mad energy, the love for Emerson he professed in my English class. A quarter of the students we worked with were at the school for drug abuse, the others had social/emotional issues, learning disabilities, or a combination of all three. We were viewed as one of the best therapeutic boarding schools in the country. We counseled kids in three-days-per-week groups. Just the day before, I sat across from a girl and spoke in a soft tone as she held her head in her hands and sobbed. Her long red hair fell around her wrists like spun fire. “I can’t believe I’m here,” she choked. I know, I said. I know.

At graduations, I was always a favorite to speak on behalf of a graduating student. For example, I discussed how hard it’d been for ___________, that he’d overcome massive trauma. Back home, he saw someone get tied to a tree and then set on fire for not paying a drug dealer. The sound of that boy screaming woke him up every night. This young man learned, I said, to love his family, and himself, again. At the end of the speech, as with all my speeches, I cried. The student cried. His family and the other well-dressed families cried. “You can do this,” I said. We embraced and then, bravely, he went back into the world.

We found Psychs where we did last time, hanging out in front of the small, withered park downtown. He wore a red Chicago Bulls jersey, cargo shorts and was sitting indifferently atop a cement ledge. I don’t think he remembered us. As we drove him to the place, Billy asked if I could front the money for the heroin. I said I didn’t have the money, thought he had it.

“What,” Psychs said from the back. “You ain’t got the fuckin’ money?”

“No, no, we’ll get it,” I promised. “Where’s that ATM machine around here?”

The last time we did this, which was also the first night we ever met Psychs, we managed to do the exact same thing: try and score heroin without remembering the money. “It’d be a bad night to get knifed,” Psychs said then, and I pictured a cartoon Arabian sword being pushed through the seats and into our backs, Psychs rolling our stupid corpses out onto the curb. “Stay in the suburbs,” he’d say as he drove off in the Jetta.

This time, after collecting one hundred dollars from the ATM, we pulled up in front of the apartment and Billy turned to Psychs. “Don’t give us any of that white boy shit,” he said. “We want the normal dime bags, ten of them.”

“Hey, don’t fucking talk to me,” Psychs said. “Just give me the money.” He took the five twenties, quickly exited the Jetta and crossed the dark street, disappearing like a spider down a flower’s throat. I was starting to feel hung over and the coke had worn off.

Silently, Billy and I waited ten minutes.

“That motherfucker better not screw us,” Billy said. A car moved softly down a cross street, left no evidence that it had ever been there.

“Fuck it. I’m going in.”

“In? In where,” I asked.

“Don’t worry, I’m just gonna see if he’s in the stairwell or something.”

Billy left and I sat in his Jetta alone.

I kept waiting for the police to roll up behind me with their spotlight blinding the mirror, their careful approach to my door as they asked to see my hands.

I could feel sweat prickling the back of my neck.

Someone came out of the building and walked with great purpose towards me.

Billy opened the door and hopped in. “Hold these,” he ordered. I looked at my hands and counted ten small plastic bags. He started the car and we drove off.

“I already had a taste,” he said, sliding the Jetta smoothly into third gear. “It’s fucking amazing.”

And I believed him because what other choice did I have?

Fragile Threads, from Earth to Sky: A Conversation Between Cindy Rinne and Toti O’Brien

Cindy: The story looks at gay rights, women and those identifying as women having a voice. Although the story is set in the distant past, the issues are current.

Toti: Mine is not a story of flight, but it's a story of long distance, of the courage it takes to part from one's roots while still remaining, somewhere, connected.

Cindy Rinne creates fiber art and writes in San Bernardino, CA. A Pushcart nominee. Her poems have appeared in literary journals, anthologies, art exhibits, and dance performances. Author of: The Feather Ladder (Picture Show Press), Words Become Ashes: An Offering (Bamboo Dart Press), Today in the Forest with Toti O’Brien (Moonrise Press), and others. Her poetry appeared in: The Journal of Radical Wonder, Mythos Magazine, Verse-Virtual, and others.

*

Toti O’Brien: Cindy, I remember when I first heard you read from The Feather Ladder. You were handling the very first copy! The book had just been released. It must have been the Fall of 2021—of course, we were grappling with the pandemic, trying to keep our creative souls and hope alive. I was sitting on the floor of the gallery where your reading took place in conjunction with an art opening. I recall being literally carried upwards by both your imagery and delivery, lifted in a world magical and mysterious that defied gravity. In a landscape of intermittent lockdowns and endless isolation, your aerial verse invoked the idea of escaping the labyrinth from above.

Can you briefly explain the core idea of this book?

Did you actually conceive it during the pandemic? If not, did the pandemic influence its development or its final shape?

Could you say something about where the original impulse came from?

Cindy Rinne: This novel in verse is a coming-of-age story for The Feather Keeper. He is sought out by a group of birds to help them fulfill their dream. He also discovers his mysterious origins because of this quest. Prophecies weave through the story for The Feather Keeper to be fulfilled as he chooses to take this journey.

Owl responded, Owl magic to protect your skin. It will be a night to your fingers.

The original story, which was longer, was conceived several years before the pandemic. The only effect the pandemic had was that the publisher delayed publication until things opened again.

The original impulse came from an idea about a group of birds speaking with The Feather Keeper about their idea to build a ladder reaching from earth to the sky. Then humans could get off the ground and out of their routines.

I made up this myth based in Neolithic times. In the story several times, their new idea receives opposition because there is fear of change. There is also support. As the journey continues, several characters who are not birds help them and The Feather Keeper. They meet with Sitka Spruce, Thunder Sun, Clear Sky, and Stone Woman.

A year later with various versions of COVID, Pages of a Broken Diary is launched in the same gallery captivating the audience. Your delivery is passionate. Although I know you well, there is much to discover in this book. Can you talk about the form in this book? Do you see it as a memoir in fragments through prose or short stories? Why not poetry?

This book seems to go deeper and is your most vulnerable. “I am an orphan at soul.” The origins? Why now?

TO: Thank you, Cindy. “There is much to discover,” is probably the best comment a book could wish for! I see Pages of a Broken Diary as a collection juxtaposing different “formats” and “tones” rather than different “genres.” Some “pages” are clear, memoir-like narratives. Other pages are indirect, elusive. Some are very brief and read like prose poems. This contrast of voices and moods is deliberate. For me, it echoes the kaleidoscope of memory—the way life and its complexities speak to our mind/heart when we reflect on our past.

The book “reads as a memoir” because it strongly focuses on childhood and coming-of-age, family and relationships, motherland and displacement. Still, it doesn’t trace a life story, and the margins between fiction and nonfiction are never defined. My intent was to gather into a cohesive whole my reflections in the above-mentioned areas, delving into them with whatever means I could handle—thoughts, feelings, recollections, hypotheses, sheer imagination, irony, paradox, the lyrical, the documentary, you name it—and then offer to the reader not the result of my questioning, but the questioning itself.

I would think of a memoir as a detailed photograph, with recognizable scenery and portraits—sometimes, as one of those collages juxtaposing many small pictures—sometimes, maybe, as an album one could leaf through. Pages is none of this. Imagine it as a scatter of incomplete, blurred snapshots. Some of them might be distinct, and you seem to recognize this or that—but in the next one the same face is blurred—in the next one, the character or the landscape or the epoch have changed. Think of it as a bunch of puzzle elements sparse on a coffee table. The puzzle must be assembled, and each reader will do it in her unique fashion.

Origins, you say. I love how you simply speak the word, how you just pose it there. Are you asking me why I look back? What I am seeking? Let me ask you first, then… Why did you made up a myth based in Neolithic times?

CR: I decided to push the story back in time when community just began to be a concept and tribes with a chief were starting to form. The Neolithic culture includes farming and the use of metal tools. This was a time when the earth, goddesses, and the stars were honored. We need to bring this back. They wore animal skins. Cave paintings show hunting. I could include hyena and lynx.

The Feather Keeper talks with animals instead of hunting or farming. He’s still a nomad. This character didn’t begin as a Two-Spirit who embodies both the masculine and feminine. I discovered this term at an art exhibit of photographs after the myth had been written. It felt right. He probably would have been accepted back then, but LGBTQ Americans and beyond remain vulnerable to violence and hate. I write ancient / present and brought issues of today into the story.

The book is about social justice, courage, and magic. Myths last because of truths contained. I am a storyteller. Most of my poems contain a story. Sometimes I tell the story over several poems like this novel in verse does.

The style in Pages of a Broken Diary is conversational. Unpolished. Raw in places and lyrical in others. I feel I am with you in the push / pull of uncertainty, a timid present. How spontaneous is your writing? Do you think this allows the reader to bring their story easily? Is this important to you?

TO: As you say, the style in Pages is sometimes conversational, sometimes lyrical. I would not say unpolished because, as an ESL writer, polishing for me is a must—it needs to be agonizing, relentless. But, yes, my first drafts are spontaneous, unplanned, uncontrolled. To me, that is the only way to let “row” and “vulnerable” freely emerge. When they do (boldly show themselves in the nude) they speak to the reader in a different way. Closeness to the reader is important to me. I seek for a dialogue to be established, as authentic as possible, even if mediated through the written page. When I write in a conversational mode I am truly speaking with you, whoever you are. When I withdraw into the lyrical, elusive, non-linear, I am inviting you to behold a monologue happening in a “public sphere of privacy.” I am alone, but the spotlight is on, and you are welcome to witness the “push / pull of uncertainty.”

I firmly believe that the most vulnerable, the most open is the writing, the most it allows readers’ feelings and stories to resonate and emerge in response. And that is the whole point, is it?

You have mentioned “fear of change” as one of the motifs in your book. It is what creates obstacles that need to be overcome in order to build the ladder. But your novel is also permeated by the opposite force, a desire for change, which finally prevails. I wonder if “a desire for change” in the present is what prompts you/us to look back, as if wondering, “how did we get here?” As if, gazing at the past with clear eyes, we could see what we wish to keep and what we don’t want to repeat. Is there something in particular that your book sets to change, might be able to change?

CR: Opposition comes from those who say, Humans were not meant to fly. This can include the idea of are dreams possible? When my first book was published, I realized I was an author. A dream to have a book barely seemed possible. This dream included community from critique sessions to poetry readings. There are many allies in this story.

The ego rises up and says, You are not a good enough writer. Do people care about myth? On the other hand, others can be jealous or try to sabotage. The ladder builders face destruction but learn determination. For me it means a lot when a story or poem touches one person. You and I have discussed the power story holds.

It takes courage to follow your dream and to navigate the unknown. Pushing through the fear is a test for the birds and The Feather Keeper. He says, I will climb when no one else is willing. Recently, I decided to do performance poetry. I love making the writing real in a different way using props, costumes I make, and the movement of my body. In The Feather Ladder, he takes a stand. Opposition comes in the form of power struggles. The Feather Keeper acts in the balance of knowing when to negotiate, be humble, and when to be bold. He keeps the focus of the bird’s dream. In the process, he discovers what is important.

The story looks at gay rights, women and those identifying as women having a voice. Although the story is set in the distant past, the issues are current. I look at the situations of climate, ecological, political, and cultural chaos today. Even think about how this could be a banned book like the feather ladder falls apart. Then I wonder if I/we can find a gift to share with others like The Feather Keeper did? Can we work together to bring change and follow our dreams?

We weave worlds magical and mysterious and defy clear formats. Even in what appears to be very different books, there’s links. Discuss.

TO: Yes, there are definitely links between these two books! Otherwise, we probably would not be having this conversation. I can think of two main connections, right away. One is almost obvious. As per our visual art, we both build books out of fragments, juxtaposing bits and pieces instead of embracing a unified, fluent narrative. As per our visual art, we both use shards that are asymmetrical, different in texture and size. I have discussed my frequent and deliberate changes of tone, POV, format. The building blocks of your book are all poems, but they vary as well. The story is told by a polyphony of voices, the POV constantly shifts, even the font/format does. It seems that we both like sharp angles, such as the zigzag point you frequently use in your textiles, or my ripped shreds of papers.

Another, very strong similarity pertains to contents. Both of ours are coming-of-age story, though “age” is not insisted upon—a detail that rather likens them to tales of initiation, testimonials to a process of inner growth. Mine is not a story of flight, but it’s a story of long distance, of the courage it takes to part from one’s roots while still remaining, somehow, connected—as it happens to the unnamed character of “Her Kind,” which dreams to be attached to a pole and runs until sheer momentum lifts her from the ground. Though she’d like to be a bird, she knows she’s not one. Still, she stubbornly enjoys her parcel of levitation.

After all, my book ends on something aerial as well: the airmail letters, light as feathers, going back and forth across the Atlantic, “fragile threads creating the legend, stretched over oblivion.”

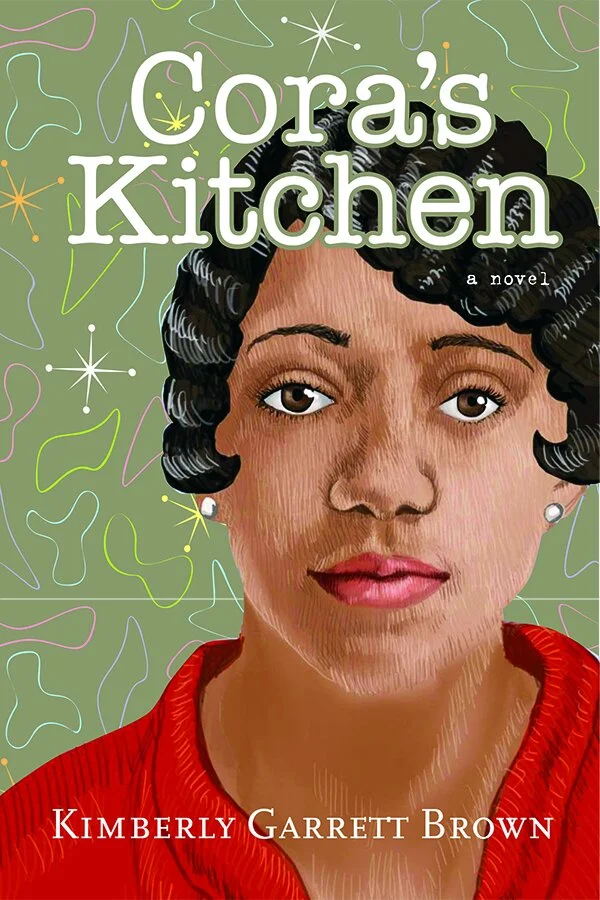

An Excerpt from CORA’S KITCHEN by Kimberly Garrett Brown

A strange thing happened this afternoon at the Fitzgeralds’. I had started supper and settled into the alcove next to the window to work on the cardinal story. The words poured onto the page as if the pen had a mind of its own. I didn’t hear Eleanor come in. When she called my name, I jumped.

May 16, 1928

A strange thing happened this afternoon at the Fitzgeralds’. I had started supper and settled into the alcove next to the window to work on the cardinal story. The words poured onto the page as if the pen had a mind of its own. I didn’t hear Eleanor come in. When she called my name, I jumped.

“I didn’t mean to frighten you,” she said as she unpinned her hat and laid it on the table. I closed the notebook and slid it into my apron pocket.

“I hope you don’t mind. I had some time while the roast was in the oven,” I said, standing up.

“Of course not. So, you write!” she said, as if it were a shock that a black woman could write. “I have always wanted to keep a journal, but I haven’t anything of interest to write about.”

I opened the oven to check the meat. The room filled with the smell of baked onions and potatoes. The juices sizzled and popped against the edges of the pan. I had a spoonful up to my mouth when I realized Eleanor was watching me. She asked what I wrote about.

“People I grew up with back home,” I said, pouring the spoon of juice over the roast instead.

“Memories?”

“Stories.”

“Like the ones in Vanity Fair?” she asked.

“Nothing like that. Far from it,” I said, though I suppose it isn’t that far from it. A story is a story. But unfortunately, the editors haven’t changed since back in the days when I wanted Mama to write down her stories for the Ladies’ Home Journal. White editors still aren’t interested in a colored woman’s stories, because she is always going to be more colored than she will ever be a woman. They don’t believe white women have anything in common with colored women.

I moved around the kitchen to look busy while we talked. She asked how I got interested in writing. I told her my mother took me to the library as a girl and I fell in love with books.

“Cora, come sit down,” Eleanor said. “You’re making me nervous, flitting around the kitchen.”

I slid into the seat across from her. She leaned forward, her elbows propped on the table in front of her. Her green eyes were alert and bright, not like the day I found her in the dining room crying. “What did you think of The Awakening?” she asked.

The first thing that came to mind was how much I identified with Edna. But that felt much too personal to share, especially since I knew Eleanor was the type of person who always asked why. I didn’t want to have to explain why I thought being married was the same whether you’re colored or white. A woman is a woman. The only difference is a white woman has the luxury of her race and money.

“It made me think about how unfair life can be,” I said.

“I know exactly what you mean. Men get to make their own choices. Why should a woman have to live a prescribed life because of her sex?” she asked.

Or a Negro because of the color of his or her skin, I thought. She went on about the roles and expectations society places on women.

I thought about the place in Genesis 3, where God says to the woman, “Your desire shall be for your husband, and he shall rule over you.”

“God gave men dominion over women,” I said.

Eleanor considered the idea, but then suggested it wasn’t God’s intention for women to be so unhappy. “Why would He have given women thoughts and ideas, if all He wanted us to do was service the men in our lives? We were made to experience life, too. To find contentment. Peace. Don’t you want to experience life, Cora?”

“Where I come from women are supposed to find a husband and have children. Folks have a name for women who try to experience life. But men are supposed to get out and see the world. When my brother jumped on a cargo ship to Africa, my father practically threw a party to celebrate his independence. If I had done that, I wouldn’t have been able to ever show my face in town again.”

“But you came here. Isn’t that your way of experiencing the world?”

“I didn’t come here. My father sent me. He wanted me to get a good education.”

Eleanor sat back, her eyes losing some of their earlier glimmer. “Many decisions have been made for me, too. I often wonder what my life would be like if I’d had a real say.”

Earlier this morning I heard Mr. Fitzgerald scolding her like one of the children. He didn’t like what she was wearing and instructed her to change before she left the house. “Spend that healthy allowance of yours on a decent dress, for God’s sake,” he said. For some reason it reminded me of how Bud talks to Agnes as if she is the stupidest person in the world.

I wanted to ask what she would have done differently, but that was prying. Besides, folks, especially white folks, are only going to tell you what they want you to know. There’s plenty they don’t want you to know, but the biggest secrets tend to be the most obvious.

“If I had more of Edna’s resolve, I wouldn’t be afraid to do what I want to do,” she said.

“Edna ended up walking into the ocean,” I said.

“I know. But if we are too afraid to step out of our comfortable lives, we risk dying, too,” she said.

I wanted to laugh. I step on the trolley at 6 a.m. in order to make it to their house by 6:30 to make coffee. And before I worked at her house, I’d have to be at the library by 7:30. Comfortable is how I might describe my shoes, but never my life. “I’m not as worried about living as I am about surviving,” I said.

Eleanor picked her hat up and tapped it lightly against the table. “Life can be so frustrating. But I refuse to accept that there is no hope. I want more. Don’t you?”

I glanced around her spacious kitchen. Small puffs of steam seeped around the edges of the white enamel of the oven door. The copper faucet glistened as sunlight reflected off the hammered surface. How could I explain that if I had what I wanted I wouldn’t feel envious of her porcelain cast iron sink with the attached drainboard? My house would be quiet during the day, but especially at night because I wouldn’t live in a crowded building with more families than apartments. Or pay twice as much rent. Or worry about my son walking to the store even though, thank God, we don’t live in the South. My husband would be able to play at Orchestra Hall with world-class musicians instead of Rueben’s rundown nightclub. And I would be in my own kitchen, cooking my own supper.

“Of course,” I said.

“What stops you?’” she asked.

My thoughts run through all the reasons why it’s hard for Negroes to accomplish anything. But I could almost hear my father’s voice saying that’s just an excuse.

“I don’t know,” I said.

Eleanor nodded and stood up, the lines in her forehead visible for the first time. She picked up her hat and left the room. I sat there for a few minutes, replaying our conversation.

Even now, as I lay here unable to sleep, I wonder why I let myself run on so. It’s so easy to talk to her. I forget that she’s not my friend. Tomorrow, I’m going to keep my mouth shut no matter what she says.