Connecting Through Chinese Cookery: A Conversation with James Beard-nominated author Carolyn Phillips

I hope to not only encourage people to remember the foods and to cook them, but also to appreciate them. You can have a great chef, but chefs need to have a clientele with sophisticated understandings of what is being served to them.

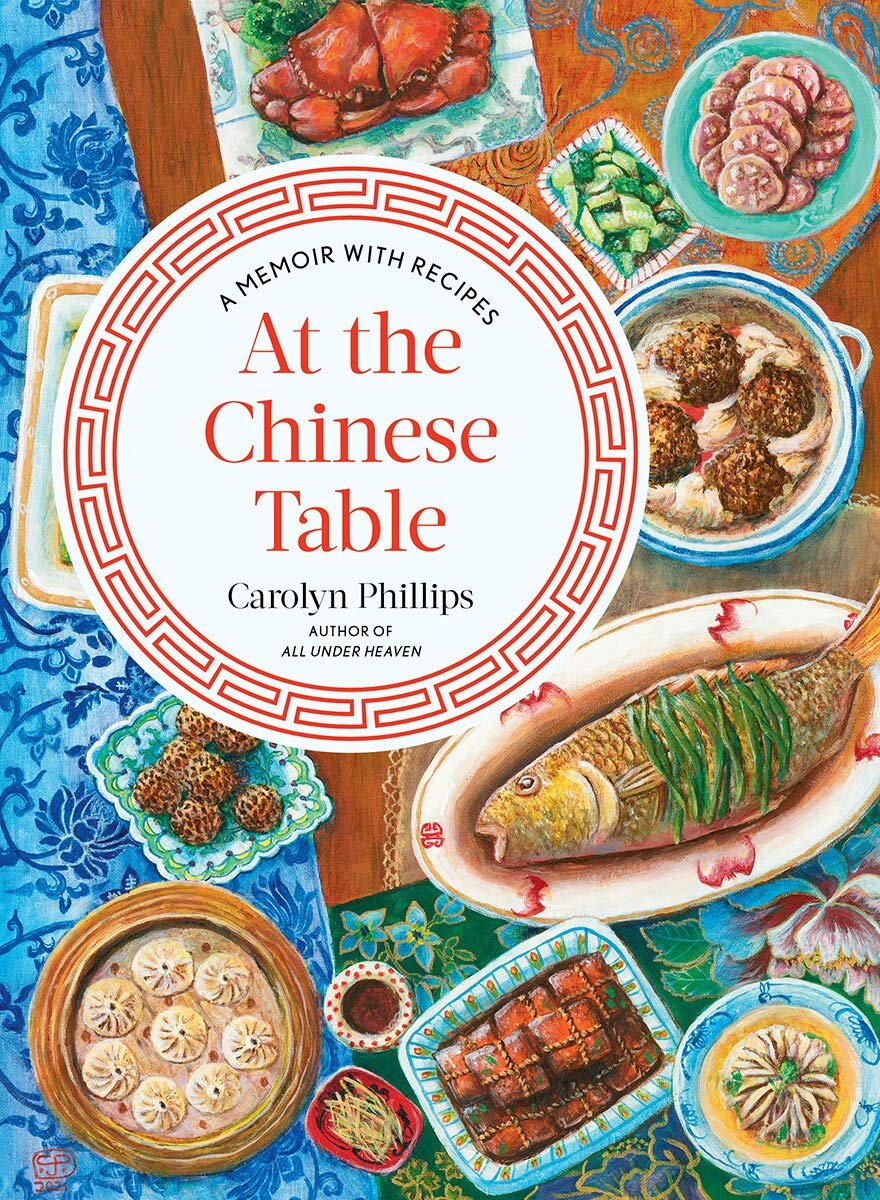

Forty years after she moved to Taiwan, Carolyn Phillips’s first book, All Under Heaven, was a finalist for the James Beard Foundation’s International Cookbook Award and her second book, The Dim Sum Field Guide: A Taxonomy of Dumplings, Buns, Meats, Sweets, and Other Specialties of the Chinese Teahouse, also came out that year. Drawn to her background and the story of her cross-cultural marriage to author and epicurean J.H. Huang, which she discusses in her latest book, At the Chinese Table: A Memoir with Recipes, I recently sat down to speak with Phillips over Zoom.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: When you first landed in Taipei in 1976, Taiwan was at a crossroads. Longtime leader Chiang Kai-shek had just passed away a year earlier and across the Taiwan Strait, the decade-long Cultural Revolution came to a close as Chiang’s nemesis, Mao Zedong, also died. When you got to Taiwan, what did you know about the politics of the region and did you understand what a pivotal time it was?

Carolyn Phillips: I was an oblivious kid. I was just out of college and had no idea what I was doing. I didn't even know why I was really there. I wanted to learn Chinese, but I didn't know what to do with my life. I was like a headless fly with no sense of direction, as my mother-in-law used to say. So, no, I really didn't understand anything and was slowly figuring out what the world was about.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: This was at a time when the United States was in the Equal Rights Amendment era and women were no longer expected to marry, have kids, and stay home right after finishing school. What was your biggest surprise in Taiwan when it came to women's equality? Certainly your mother-in-law was very strong and you learned a lot about the women in J.H.’s family, but was there something else that showed we are all much more alike than we are different?

Carolyn Phillips: At that time it was at the very tail end of the Confucian era and still very much a stratified society where men had all the power. Women had very little say, even over their own children. As I mentioned in the book, if you got divorced your children belonged to your husband. Lots of women suffered and were expected to work for their in-laws.

So I had to modify my behavior because it would be very easy for people to assume I was a “bad girl”. I had to stop smoking and came to never drink. But I’ve always been a feminist. Going to Taiwan was like jumping back into my mother's generation where it was all a one-way street. Men could do what they wanted and women had to toe the line. But in Taiwan I learned not be judgmental and realized I couldn’t impose my views on others. I made good friends with women in Taiwan, though, and they'd tell me their sides of the story.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: Did you see changes in the time you were there?

Carolyn Phillips: Yes. I became fascinated by the feminist movement in China, particularly around the 1911 Revolution. Women began to finally gain certain freedoms and I talk about that a little in my book with my husband's maternal grandmother. Before then, women were absolutely uneducated and had zero rights.

And so I started talking to elderly women in Taiwan. In chapter two of my memoir, I talk to Professor Gao, a feminist. I read many books and tried to figure out what was going on in Taiwan, because they, too, were on the cusp of change. The courage and strength of these women is absolutely phenomenal. Women are now increasingly not marrying in Taiwan, and it's also like that in Korea, Japan, and Hong Kong, where women don't need to be somebody else's daughter-in-law and don’t need to have children in order to be fulfilled.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: Another thing I loved about your memoir is that you include gorgeous illustrations you drew yourself, along with recipes you learned from your time in Taiwan, your travels in China, and from J.H.’s family. It's really a multifaceted book, and it's going to be difficult for me to read more traditional memoirs after being so spoiled by yours. Did you plan to include illustrations from the beginning? You'd already illustrated your two other books, The Dim Sum Field Guide and All Under Heaven.

Carolyn Phillips: My publisher really wanted to have illustrations. I had originally started out with illustrations in my first book, All Under Heaven, because McSweeney's, my publisher at the time, had asked if I wanted to have photographs or illustrations. I asked about the difference between the two, and he said the cost of illustrations was much less, so I could have more recipes. So I said let’s do illustrations. And because I’m a total control freak, I did the illustrations myself.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: Were you trained in art? Your illustrations are so beautiful.

Carolyn Phillips: No, I was never trained in art, officially, although I did take lessons in painting and so forth in Taiwan. I worked at the National Museum of History for five years and we had some of the greatest artists in Taiwan. So I would watch them paint and learned from them. I always loved to draw, although my mom discouraged it. I had my Rapidographs when I was in high school and thought they were the best thing ever. I guess this sort of carried over.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: So with your memoir, it was just kind of a given that you would illustrate it?

Carolyn Phillips: Yes. They really wanted to have illustrations and I think that was part of the sell. They liked the idea that it’s unique. Not too many people illustrate their own books.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: Dim sum is one of my favorite meals. It's also that whole experience you write about: sitting for hours in large dim sum stadiums, sipping tea and chatting with friends or family. Can you talk about how you came to write The Dim Sum Field Guide?

Carolyn Phillips: I had my first great dim sum meal in Hong Kong on Nathan Road not too far from the Star Ferry. I knew this American nun who was living in Hong Kong, and she and her sister nun invited a couple of my friends and me to have dim sum. At the end, we got into a huge tussle over the bill, which of course is very Chinese. So these two white women are duking it out in the middle of the dim sum parlor and everybody's practically taking bets.

I was thrilled by the whole concept of dim sum. When you get an American breakfast with waffles, eggs, and bacon, it's delicious, but after two or three bites you wonder if you want to have forty more bites of the same thing. With dim sum you can slowly go through steamed, pan fried, deep fried, and baked, and everything is totally luscious, and I'm drooling as I speak.

The seed for the book came when I first got that contract with McSweeney’s for All Under Heaven. My editor was Rachel Khong, and she was also an editor at Lucky Peach. She asked if I wanted to write something for their upcoming Chinatown issue. And so we came up with the idea of a field guide—like a bird guide book—with sixteen different dishes. When Lucky Peach had the MAD symposium in Copenhagen, they turned the article into a little pamphlet to pass out. While I was waiting for All Under Heaven to finally get published, I wrote to Aaron Wehner, the editor at Ten Speed Press, and told him what I’d done at Lucky Peach and asked if he’d like to do a whole book on this. And he said, “Sounds cool.”

Susan Blumberg-Kason: That came out the same year as All Under Heaven?

Carolyn Phillips: It came out the same day! Only Prince and I have done that. I’m in a good company with The Purple One. It was a thrill. Ten Speed Press took over the publishing of All Under Heaven because McSweeney’s was going through some issues so they did it in cooperation with Ten Speed.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: So I have to ask this because I'm sure readers will wonder about it. Have you ever been questioned on your authority of Chinese food?

Carolyn Phillips: I've really never gotten any pushback, knock on wood. What I have received is a whole lot of love, especially from the Chinese American community. For example, there was a lady who lived in Central Valley in California and she described these cookies that her grandma used to make. But she didn’t know the name. I went through the many cookbooks I have in Chinese. When I finally found a couple of recipes, I asked her if they sounded like it. After several tries, she finally said that’s it. So if I can help somebody like that reconnect with their family, I just feel like I’m doing something right. As long as you're not approaching it as cultural imperialism and if you're doing it with respect and with love and with humility, I think it’s okay.

My role model has always been Diana Kennedy. I think she’s one of the very few white women who has actually become an expert in her field. Even the Mexican government has recognized her contributions, and she’s received the Order of the Eagle.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: It's good to think about all these things because there are so many benefits to having these recipes and these methods of cooking.

Carolyn Phillips: The reason I wrote All Under Heaven was because the foods that my husband and I loved eating in Taipei during the 1970s and 80s were classical cuisines of China—and there are many cuisines in China—that had come to Taipei. We were the beneficiaries of this and ate like kings and queens many times a week. But when we came to the States, they didn't exist. When we went back to Taipei to eat, these places no longer existed either, because the chefs were passing away or retiring. The younger people didn't know what it was they had had. I hope to not only encourage people to remember the foods and to cook them, but also to appreciate them. You can have a great chef, but chefs need to have a clientele with sophisticated understandings of what is being served to them.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: I think Americans have gotten more interested in food in the last ten to fifteen years. It’s a slow process and books seem a good way to bridge that and to get people interested.

Carolyn Phillips: It's a good beginning. Television is also a good way to go. Anthony Bourdain was marvelous in that way. He had that humility and curiosity I think we all aspire to, where he would eat every part of a warthog, or go into a village and eat whatever they served him, which is absolutely the correct attitude.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: You did everything that Bourdain was known for, but decades before, and one of the things you write about in your memoir is cooking a pig head. Anthony Bourdain would have made that glamorous but you did that for your family and friends.

Carolyn Phillips: A lot of it was to just win over my future mother-in-law because she was a real hard nut to crack. But she did love to eat, so I learned to cook the foods that opened her up and warmed her to me. That was a great stimulus, winning your mother-in-law over, especially when she was a warlord lieutenant’s daughter.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: Did any books or authors inspire you to write At the Chinese Table? And do you have plans for a fourth book?

Carolyn Phillips: I’m actually finishing up my next cookbook. I can’t talk about it now because I don’t have the contract yet. As for food biographies, there are so many wonderful memoirs out there. My first influence was M.F.K Fisher. She writes more sensually about food than anyone I know. Some men don’t like her. I don’t know why, but to me she always spoke to my heart. Even now I can remember her peeling a mandarin orange and placing the segments on a radiator so that the skins would slightly crisp up before she took a bite. That kind of depth of sensuality is phenomenal to me. Julia Child’s writings are wonderful. Han Suyin’s Love is a Many-Splendored Thing is based on her cross-cultural life. There is also Georgeanne Brennan with A Pig in Provence. I filled up my shelves with people, especially women, who went to another country and sort of lost themselves. I’m really fortunate to be on the James Beard Foundation’s Book Committee. We see a lot of really great food writing and we’re so lucky to live in this world where food writing is appreciated. Kiss a food writer!

Susan Blumberg-Kason: I just love that ending!

Carolyn Phillips: But just don’t kiss them during the pandemic.

Asking the Right Questions: The Overstory by Richard Powers

More notably, The Overstory asks the important questions. How much is enough? How long do we have? Do trees have rights? Does the end justify the means?

The best arguments in the world won’t change a person’s mind. The only thing that can do that is a good story.

The Overstory by Richard Powers, whether it changes your mind or not, is a damn good story. It is also more than just a story.

I picked up The Overstory months ago in a moment of inspiration. It is a 2019 Pulitzer Prize winner, but more importantly, Keanu Reeves had recommended it in an interview. Since I would trust John Wick with my life, I figured I could trust him with recommendations. And yet, committing to a tome of 625 pages seemed as ambitious an attempt as the book itself.

I drifted in and out of it for many weeks, eventually picking up pace with my reading once I decided it would be my April read for my monthly reading challenge. It took me another six weeks to plod through it, but once I had finished, I flipped back the volume — now extensively dog-eared and interspersed with pressed flowers — to its beginning, and I inscribed under the title the two sentences that open this review.

As I write this now, I realize how challenging it is to comment on The Overstory without resorting to blatant exhortations at people to “give a f*ck about trees”. But we’ll come back to this.

The Overstory is divided into four parts. Roots, Trunk, Crown, Seeds. Each chapter in Roots is a mini bildungsroman of one of the main characters of the novel, of which there are as many as eight/nine. They are as diverse as could be; a farmer’s son who becomes an artist, a reclusive child fascinated with ants, an IP lawyer and an amateur theatre enthusiast, a loadmaster in the Vietnam War, the engineer daughter of a Chinese immigrant, a computer nerd in a wheelchair, a hearing and speech impaired young scientist, and a carefree student living a risqué lifestyle who dies for seventy seconds and then comes back to life, serving as a bridge between the Roots and Trunk of the novel.

As I read Roots, it felt like I was reading a collection of short stories, each story coming across as objectively detached. These chapters seem as unconnected as they are different, like trees and men. But as pointed out more than once, “you and the tree in your backyard come from a common ancestor”. And so it is that the nine protagonists share a common thread. For one of them, it is stated outright, “he owes his life to a tree”. The rest, in their own strange ways, do the same. Even the one broken by a fall from an oak. Even the one to whom trees mean nothing but the stage prop forests of Birnam Wood in Macbeth.

It is only about one-third into the book — we’re barely through the understory — that Olivia, the resurrected, finds Nicholas, the tree artist. Soon, more roots come together to form the trunk. Five of them unite to form the heartwood. Much of the story hereon is focused on the battle for the Californian redwoods, waged against timber companies working their way at a suicidal pace through the country’s green cover, but a battle is a mere milepost in the trajectory of the greater war — the endless struggle of planet versus profit.

One of the key tenets of The Overstory is the delineation of this struggle and its stakes — the tree of life is on the brink of collapse. Mankind’s hunger for ‘just a little bit more’ is endless, and endless exploitation of resources within a finite system can only lead to one outcome. Climate crisis is already upon us, a pressing life-threatening reality, and deforestation alone has been a bigger factor than the carbon footprint of the world’s transportation taken together. A key character proposes damage control, “What you make from a tree should be at least as miraculous as what you cut down.”

The other is simply this — trees are the most wondrous products of four billion years, they’re sentient, they’re social, and they need our help.

Yes, The Overstory tells you why you should give a f*ck about trees, but it also narrates the story of men and women, those who are brought alive in its 600 odd pages. From failing to remember their names in the first part, to witnessing their journeys of self-discovery, to being moved to tears in the end pages by their acts of love, sacrifice, betrayal and redemption, the "best novel ever written about trees" (Ann Patchett) takes you on a tumultuous ride through the experiences and emotions of its bipedal heroes.

More than anything, The Overstory amazed me with its details. The sheer volume of minutiae — of plants and their species and their behaviours and habitats — had me constantly wondering how long and hard the research for the book must have been. It took Powers five years to write The Overstory. But Powers is known as the ‘the last generalist’ and known well for writing masterpieces in the realist tradition. The Overstory is one triumph among many.

And yet, there is such a thing as too many details. The Overstory could have been part botany text if not for the seamless way in which tree talk is interwoven into the story, but reading it can be exhausting at times. There were pages when the descriptions wore me down to the point where baobabs and their buttresses and bald cypresses and cedars all seemed to merge into one another.

The scope of the story is grandiose, even overreaching, spanning the entire lives of many of its characters. The sheer chronological scale makes it necessary for chunks of the story to be summarized, which Powers does with skill. This, however, renders some parts too simplistic, as if the writer couldn’t afford to have his readers stray in contemplation. Dilemmas are dissected, motives and actions explained, evidences clearly signposted.

Nonetheless, The Overstory has more than one trick up its sleeve. Structurally, the book is a conceit. The story unfolds like the whorls on a tree. A bunch of roots unite to feed its trunk, extending into the crown, which reaches out towards the sky and in a final act of bountiful giving, disperses its seeds into the cerulean expanse.

More notably, The Overstory asks the important questions. How much is enough? How long do we have? Do trees have rights? Does the end justify the means? It is remarkable and scary how pertinent these questions seem to be in the current times; a time of bushfires and cyclones and earthquakes and pandemics and rising temperatures and weakening magnetic fields. Even when the ideological tussle of environmentalism vs capitalism veers off into the territory of ecoterrorism, absolute censure of the acts of vandalism and arson is difficult in view of what is at stake. Violence, by all accounts, cannot be justified, but what when it’s state-sponsored? When the city’s finest are the ones pouring pepper spray into the eyes of peaceful protesters? Who do you call when the police murders?

One of my favourite modern artworks is the photographic self-portrait of Adel Abdessemed, French-Algerian contemporary artist, where he set fire to himself and struck a defiant pose in response to contemporary events like Arab Spring and Syrian Civil War. A dominant interpretation is that it represents the incitement of violence in response to the injustice existing in the world. Similar sentiments echo through The Overstory, and whether it changes your mind or not about the merit of desperate measures in desperate times, it will at the least have you acknowledge it as more than just a good story.

Some may even call it radical. Radical, a word that comes from Radix. Root.

The Analyst by Molly Peacock

The Analyst is an elegy for a living woman—at least, for the position she once held. She was the psychoanalyst the poet confided in and relied on for decades. A stroke now prevents the analyst from working in that capacity.

The Analyst is an elegy for a living woman—at least, for the position she once held. She was the psychoanalyst the poet confided in and relied on for decades. A stroke now prevents the analyst from working in that capacity. In addition, this book invokes elegies for other losses in the poet’s life: the death of her father, mother, sister, an abortion, a divorce. The therapist supported Peacock throughout that painful sequence of events. But now, as the beloved mentor succumbs to limitations imposed by the stroke, Peacock—in a role reversal—becomes more whole and vital.

She does this by looking back. For example, the broken relationship with the author’s sister was put into perspective by this remarkable therapist. Peacock writes, “Thank you for witnessing this use of the imagination: / I began to creep away from the crevasse, / it was war, away from the ocean of her heroin addiction.”

It would be an oversight not to see these poems as also mourning facets of Peacock’s self, “I believe in being killed, and I believe in poetry.” In release, in “dying,” she is liberated to create. The role(s) the analyst played through transference—as lifeline and confidant—have been manifested in the therapeutic act of writing poetry. However, healing is rarely perfect or complete. Peacock admits:

And partly healed injuries have

their own torque … Bones

(minds have bones) grow even

after they’re operated on …

human growth is complicated

As she delves into her abiding love for the analyst, she also explores how that woman has helped her to navigate and endure anguish:

Thank you for not believing me when I said I was suicidal

(my dad had died and evaporated into smoke

—that rageful man, yes, slowly I admitted I had

half his genes—bomb—vaporous beneath

the heavy gray apartment door).

Each death, or transformation, is guided by the loving perception of the titular analyst. In addition to being an elegy for the relationships and histories that have been subsumed by others, this poignant book is also a love letter to the confidant:

Thank you for that silhouette I saw

wearing your earrings and belt

as I stood at a podium before a darkened theater,

the vast audience unmoved after I failed to entertain.

Now, that stalwart mother-figure has been felled by fate and physiology. As the beloved analyst abandons speech, the tool of her métier, she learns to wield another one like a wand: the paint brush. She returns to an old love—painting. Although this actually occurred, it can also be seen as a metaphor for the growth that the analysand shared with her analyst. Indeed, this book is a tribute to the transformational power of art. While the title refers to the therapist, Peacock—her patient, student, daughter—has been reborn and redeemed through her multifaceted literary gifts: “[Y]es, each of us is many-roomed.” This is a nod to the word “stanza,” meaning “room” in Italian. Certainly, Peacock is a deft practitioner of the architectonic aspects of poetry. As such, it is worth noting the range of forms and voices that swirl with authority throughout this collection. It’s as if each poem were searching for the boundary beyond which pain ceases to exist. And yet ache (rage and fear) drives these poems. They fuse into a dissonant dirge:

Our jaws could eat cement.

Anger chomped at

the marriage wall

ate the glass windows of friendship

and bled from its stone teeth,

muttering, Oh not, I am not, at all, at allI am not at all

The elegiac focus extends to a contemplation of the poet’s own mortality, which she handles without ever being maudlin or melodramatic. We even catch a glimpse of the brutality of American history. At the New York Historical Society, the poet and her analyst catch sight of Dying Indian Chief, Contemplating the Progress of Western Civilization: “You duck beneath him with your wobbly cane / then upturn your face toward his, contemplating // his sober view of hysterical society.” This brings to mind The Dying Gaul, a sculpture that captures the anguish of conquest, the erasure of a culture, and death. How the human body is like history, with its fragility and indignities. The trope of the stroke extends its shadow. This recalls Susan Sontag’s seminal book, Illness as Metaphor and Aids and Its Metaphors. Despite lamentation, a striving to prevail permeates these varied poems:

and live the raw I am, as you do now,

relearning how to showthe few of us who stay in touch

how to twist and learn.

Variety enlivens the forms of the poems. Form, for which Peacock is prodigious and rightfully famous, has been liberated into a new, more raucous version. The effect is thrilling. Formed, yes. Formal (in the sense of solemn and constricted), no. These trenchant poems burst every seam that attempts to bind them. The result is one of luxuriantly musical phrasing. Here, Peacock employs terza rima:

Three Tibetan monks make a sand painting

(under spotlights) in a reverential hush,

the circular world before them everything:a cosmos, a brain, a divine palace lush

with lotuses and pagodas in children’s

paintbox colors. “Excuse me, my friend isrecovering from an accident …”

To enter more deeply into the world of images as words, Peacock bends her voice to a place where visual details take over. The image, like a Chinese character, carries the weight of thought and emotion. In this, she inhabits the analyst’s visual locus, where color and form have meaning, where a leaf flickering in a breeze is a poem. Simile is too tenuous. Transformation occurs; this is the realm of metaphor.

Here,

when all are there,

the sky shows through

a peephole: a leaf hole

shapes

getting nowhere

out of the blue.

Through loss upon loss, metamorphosed into the marrow of Peacock’s language, she writes, “Only when / something’s over can its shape materialize.” The losses reconstruct themselves from vapor, rise from these pages, and insert themselves into the reader’s mind, where they will not be forgotten.

A Conversation with Bonnie Jo Campbell and Andrea Scarpino

One might make the argument that two of the strongest voices in contemporary Michigan are Andrea Scarpino, representing the Upper Peninsula poetry scene, and Bonnie Jo Campbell, representing the Lower Peninsula fiction scene. The strength of their voices comes from a combination of having unique, distinctive, and passionate style and subject matter on the page, furthered by both authors willingness to tour extensively, notably to rural communities in the state.

One might make the argument that two of the strongest voices in contemporary Michigan are Andrea Scarpino, representing the Upper Peninsula poetry scene, and Bonnie Jo Campbell, representing the Lower Peninsula fiction scene. The strength of their voices comes from a combination of having unique, distinctive, and passionate style and subject matter on the page, furthered by both authors willingness to tour extensively, notably to rural communities in the state. Scarpino is the 2015-2017 U.P. Poet Laureate whose latest book is What the Willow Said as It Fell (Red Hen Press). Bonnie Jo Campbell is a previous National Book Award finalist whose current book is Mothers, Tell Your Daughters: Stories (W.W. Norton & Company).

*

RR: Both of you are brilliant with titles. I’m a big fan of the cryptic Once, Then and the best title of 2015 might be Mothers, Tell Your Daughters: Stories with its lovely double-entendre of “Mothers, tell your daughters stories.” Can you talk about your book titles?

AS: Thank you, Ron! Your compliment means a lot to me because I really struggle with titles. When I was doing my MFA, one of the recurring criticisms of my workshop submissions was that I needed a different title, and I often go through dozens before I find one I really like. They just seem so final—like naming a child.

I really like titles that simultaneously shape the reader’s expectations and withhold a little bit of information from the reader. I want the reader to be interested in opening my book, but I also don’t want to be too explicit about the book’s content. In both my poetry collections, the titles developed from lines within the book itself which I hope readers will recognize when they’re reading. In my second book, the line, “what the willow said as it fell” is followed by, “Take this body, make it whole.” So I liked What the Willow Said as It Fell as a title in part because I’m hoping the idea of wholeness, and obviously the fact of the body, shines through the poetry.

BJC: Thank you, indeed, Ron! I’m with Andrea that titles are hard. And I might even go so far as to say that a work is not finished until it has the right title on it, and for me the title is often the last element of the story or collection to come to me. That said, after I get the right title, by settling into the final understanding of my work, then I have still more work to do, adjusting the whole work slightly to the title. The titles to all three of my collections have great stories behind them, and I’ll say that I spent months coming up with Mothers, Tell Your Daughters. I had this story collection, but didn’t quite know what it was about. After trying out hundreds of other titles, arguing with my editor and agent, and stressing endlessly, I finally came upon this one. It resonates especially for me because it’s a line from the song “House of the Rising Sun” when sung by certain female artists. Once alighting on that title, my editor and I made some adjustments to the collection, leaving out a few stories that no longer fit and requiring me to write two new stories, including the title story. American Salvage has a similar story behind it, in that the title story was the last one I wrote. My novel, Once Upon a River, has a different story behind it. My agent came up with that title in the shower. We sold the book with that title, and I didn’t like it for a long while. Finally, when I saw the title allowed me to be fantastical, I embraced it, and I still like it.

RR: You both write about suffering frequently. What role does suffering play in your fiction and poetry? Do you handle it as redemptive or existential?

AS: I don’t think there is anything redemptive in suffering. It’s just suffering: it just hurts. I actually respond very negatively to suggestions that suffering makes us better people or enriches our lives in some deep way. I know some people derive meaning from their suffering and I’m glad for them when that’s the case, but the only meaning I’ve been able to derive from painful moments in my life is this sucks. I want this to end.

Suffering is an integral part of being alive and being human, which is why I so often write about it—I don’t think a single human being is spared suffering. And yet, we so often like to pretend we don’t suffer. We’re told to put on a brave face, and women especially are told we should smile no matter what is happening in our personal lives. So I think it’s incredibly important to acknowledge and sit with suffering, to understand it as a central human experience, and to appreciate the suffering of others around us. And writing and reading about suffering can help us with that.

BJC: I tend to write about what worries me, and the suffering of others worries me immensely. We fiction writers tend to write about suffering that comes about both because of circumstances and also because of the nature of one’s character—it is most interesting when a character has at least partially brought about his or her own suffering. I don’t write as a sociologist, and my main interest is in exploring the human character, but I am glad when my readers tell me that they have more sympathy for the sorts of folks they encounter in life because of my stories. Like Andrea, I see suffering as universal. Nobody’s life is easy when you come down to it—we want to pretend some people swim effortlessly through life’s waters, but life is hard for everybody a good portion of the time. And while I don’t see suffering as inherently redemptive, I do think it can sometimes spur a character into action.

RR: What religion do you identify with? What’s your religious/spiritual background?

AS: I don’t identify with any religion in all honesty. My father was Catholic so I have spent a fair amount of time in the Catholic Church, and my mother identified as Quaker for a while, so I spent time at Friends Meetings. I also grew up with dear friends who were Jewish and Muslim, and as an adult, I’ve read some about Buddhism. So I guess I have a bit of a smorgasbord religious background, which also means I don’t have a deep understanding of any one tradition.

BJC: Andrea, you and I need to have a beer! How have we never sat down together?

RR: The following is quoted from Mothers, Tell Your Daughters:

“I’m not going to hell,” he whispered. “God is leading me home. He has shone his light on the path to Him. God has forgiven me.”

“For what, Carl? What has God forgiven you for?”

“Forsaking Jesus.” He sounded exhausted, his voice a hiss.

“What else?”

There was a long pause before he whispered, “Jesus is my Lord and Savior, my light in the darkness.”

“How about forgiveness for hitting your wife? And your son? Is God forgiving you for that?”

Could you talk about this passage?

BJC: The passage is from the story, “A Multitude of Sins,” a man who has abused his wife and son finds Jesus right at the end and so figures he’s saved. When the husband is dying of cancer, the wife begins to discover the seeds of her empowerment. She finds herself furious at the notion of her husband receiving forgiveness. I enjoy seeing this woman become angry after a life of submissiveness.

RR: Andrea, in your poem “Homily,” you repeat the phrase, “She didn’t believe in God.” Why that repetition?

AS: My poem “Homily” was based on an experience I had while visiting Paris and walking into Notre Dame on Christmas Day: the priest was saying the mass in Latin, and the air was filled with incense and evergreen, and I was completely in love with being there and being present in the moment even though I don’t identify as Catholic. So I guess I tried to capture the feeling of wanting so badly to believe in something because the present moment is so special, but also knowing, deep down, that belief is just not there.

RR: Do you find you struggle with your religious beliefs through your characters?

AS: I don’t know if I struggle with my own religious belief through my poetry, but I definitely am a person who questions almost everything, including religious belief, in my life and in my poetry. I like feeling open to the world, and I like questioning, and I like hearing about other people’s beliefs, and I like learning how other people experience the world around them. And I find religious belief endlessly curious and interesting and rich with possibility.

BJC: I’m not interested in my own religiosity, but I am interested in the religious beliefs of others, and as a writer, I’m interested in seeing how those beliefs inform character.

RR: Bonnie Jo, Halloween appears in Once Upon a River and Q Road, notably in the passage on “Halloween [where], he’d soaped windows, strung toilet paper across people’s front yards, and once he’d found a veined, milky afterbirth from his sister’s horse foaling, and in the middle of the night dragged it onto a neighbor’s front porch.”

Are you attracted to what an old Religion professor of mine, Dr. Hough, called the Jungian shadow aspects of humanity?

BJC: Katherine Dunn’s novel Geek Love has an epigraph from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, a line Prospero says of the monster Caliban: “This thing of darkness I Acknowledge mine.” I, too, acknowledge mine!

RR: Earlier, we spoke of suffering. Both of you are connected to metaphorical center points in Michigan—Marquette and Grand Rapids. Grand Rapids/Kalamazoo is emerging as an economic and spiritual powerhouse of the state, as well as important for Michigan publishing with Zondervan and New Issues Press. There is also the complication of poverty in the far southwest regions that grinds up against Grand Rapids’ wealth. Hate groups are in that area and the recent Uber driver murders. Bonnie Jo, where you live is a very complicated place. Can you talk about good and evil in your writing, how it fits with the complexities of southwest Michigan?

BJC: I was just reading Plainsong by Kent Haruf, and I was noticing how he makes very clear who is good and who is evil in his stories. I am more interested in gray areas of human nature, in people who try to be good, but fail, and in people who make trouble sometimes. The person who has a decent job and a good family situation might go his or her whole life as a productive law-abiding citizen, while the same person, after losing a job and a spouse and children might become a meth-addicted criminal. What amazed me about the Uber shooter is just how ordinary and normal he was; that showed me that crimes are not committed by devils or evil people necessarily. Crimes are committed by people who make bad choices, and they make them for a variety of reasons, some of which we will never understand.

All we can do, it seems to me, is pay attention, keep our minds open to all the possibilities good and bad, and work to care for one another at all times. We can strive to never be cruel or judgmental.

RR: Who are the great spiritual writers in fiction and poetry?

AS: I love Marilynn Robinson’s writing, particularly Gilead. I first listened to that book as an audiobook on a road trip many years ago, and I remember just weeping while I was driving because I was so moved by the quiet spirituality throughout her writing. And that quietness is really the kind of spiritual or religious writing that I most appreciate: a quiet attention to those around us, a quiet attention to the world, a quiet attention to the connections that make us human.

RR: What issues of religion do writers need to talk about now?

AS: Acceptance and appreciation of different opinions, viewpoints, and religious traditions. Our country’s hate speech deeply troubles me, particularly as it is directed toward Muslims. But we’ve never been particularly good at accepting differing viewpoints and that’s something that writers and religious leaders and teachers and parents and politicians all need to address.

BJC: As a writer I spend a lot of time imagining how it feels to be in someone else’s shoes, and that helps me be more humble and generous toward my fellow human beings, even the difficult ones.

*

Interviewer Ron Riekki’s latest book is the 2016 Independent Publisher Book Award-winning Here: Women Writing on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula (Michigan State University Press), which includes writing from Bonnie Jo Campbell and Andrea Scarpino.

An Interview with Matthew Dickman

I have been writing poetry since High School. That’s about twenty years. One of the things that draws me to poetry is that through poetry (through art) I better understand myself, I better understand the world I live in. It’s also fucking awesome making something out of nothing! When we sit down (or stand up!) with a pen and a blank page it’s one of the only moments when we are absolutely free.

MATTHEW SHERLING: What is your favorite meal & why?

MATTHEW DICKMAN: One of my favorite meals is a grilled cheese sandwich and tomato soup. My twin brother, Michael Dickman, and fellow poet Carl Adamshick used to order that classic at a wonderful bar in Portland called Cassidy’s when Carl worked downtown . . . it is a perfect meal!

MS: What is currently your favorite album?

MATTHEW DICKMAN: My favorite album right now is 10,000 Maniacs “In My Tribe” (don’t judge me!).

MS: If you could wrap up your worldview in one sentence, what would it be?

MATTHEW DICKMAN: Worldview (at the moment) = “Lispector”

MS: How long have you been writing poetry and what draws you toward it?

MATTHEW DICKMAN: I have been writing poetry since High School. That’s about twenty years. One of the things that draws me to poetry is that through poetry (through art) I better understand myself, I better understand the world I live in. It’s also fucking awesome making something out of nothing! When we sit down (or stand up!) with a pen and a blank page it’s one of the only moments when we are absolutely free.

MS: That’s a powerful way to look at the practice of art. Can you describe your process when constructing a poem? How much editing / spontaneity is involved?

MATTHEW DICKMAN: Years ago, when writing poems, I would have complete control over the moment of a first draft. That is to say I would think of something to write about, do some research, and then write. Now it’s a more reckless experience. I sit down and begin to write with, often, no idea of what will be written. I’m moved to make something. I’m in love or sad or hopeful or have had too much coffee and so I want to let it out. What happens feels up to the moment. After that I redraft, I share it with friends and listen to what they have to say. Some poems go through numerous drafts. Others only one or two. The spontaneity is in deciding to build a boat. The editing is making sure the boat will actually sail. Though sinking sometimes feels good too!

Are there any poets who particularly inspire(d) you now or when you first got into the craft?

MATTHEW DICKMAN: YES!

Andre Breton

Dorianne Laux

Joseph Millar

Marie Howe

Yusef Komunyakaa

Dorothea Lasky

Pedro Mir

Diane Wakoski

Eileen Myles

Frank O’Hara

Bob Kaufman

Anthony McCann

Dunya Mikhail (sp?)

…to name only a couple that comes to mind today while the sun falls and night walks into Portland, Oregon…

MS: Cool! Your work seems to be considerably accessible. Is this something you shoot for? also, what is it that draws you to more ‘surrealist’ writers Breton and Haufman?

MATTHEW DICKMAN: I think the only thing I shoot for when writing is something that engages me. Of course it might not engage anyone else! Also, I believe all art is accessible, expecially if you accept a certain amount of mystery in your life…Writers like Breton and Kaufman remind me that the landscape of poetry is not the landscape of earth with fences and continents but outer space… way outer space!

MS: Can you say a bit more about your use of ‘landscape’? Also, how do you feel about ‘Objectivist’ or ‘Imagist’ poets who place heightened emphasis on the ‘thing itself’ // the “real”?

MATTHEW DICKMAN: Landscapes, for millions of years, have been both inner and outer (like belly buttons!) and our inner-landscapes affect the outer-landscapes we walk around on–as does our physical environment affect our emotional environment. Sometimes I can’t tell the two apart. The “thing itself” is never, of course, actually the “thing itself” once it’s placed into a poem or another piece of art. It has been translated, managed, slightly tuned to another frequency. A choice has been made by an entity outside of the “thing” or the “real” object removing that object from it’s (let’s say) first truth and placing it in another truth… the truth of the meaning-making artist using it or applying it in some way or another to her work.

MS: Can you tell us about your current project?

MATTHEW DICKMAN: I have a new book out this month, Mayakovsky’s Revolver, and am working on a chapbook with the poet Julia Cohen. The poems in the chapbook came out of seven days of writing together in Brooklyn. The writing based on questions we asked each other and random words.

Consider This My Warm-up Lap

In I Was The Jukebox, the orchid speaks, the eggplant waddles, and the piano shimmies through seaweed like salamander. These are the sorts of characters you’ll meet. They’ll crowd and shove and step on feet trying to get your attention, some more patient thanpeople in line at the DMV and others all aclammer to be heard.

My first encounter with Sandra Beasley was last summer. I was teaching finance to high school kids, in class six or more hours a day and prepping for countless more, yet it was poetry not numbers that was most on my mind. On exam days, I would ever so discreetly read from my computer while the students penciled away and the TA thought me busy with the next week’s lesson plans. This was how I came across Beasley’s “Unit of Measure,” the unit there being the capybara. Do you know of the capybara?

Everyone barks more than or less than the capybara,

who also whistles, clicks, grunts, and emits what is known

as his alarm squeal.

At these lines I let out a laugh, a chortle more like. The others looked up with faces unsettled between amused and annoyed. I kept my secret.

Fast forward to the colder months. A package arrived from the opposite coast, from a poet friend who was the first (and one of few) to know of my secret love for verse, and inside was a copy of I Was The Jukebox with a note that read: “Sandra Beasley is hilarious, and I think you’ll have fun with this collection.” Scanning the contents page, I spotted the title “Unit of Measure” and gasped. How did she know?

In I Was The Jukebox, the orchid speaks, the eggplant waddles, and the piano shimmies through seaweed like salamander. These are the sorts of characters you’ll meet. They’ll crowd and shove and step on feet trying to get your attention, some more patient thanpeople in line at the DMV and others all aclammer to be heard. When the sand speaks, it’s with command:

. . .Draw

a line, make it my mouth: I’ll name

your country. I’m a Yes-man at heart.

But inanimate objects aren’t the only ones present. Osiris and Beauty make an appearance. There are poems on music and the Greeks and love poems for college, Wednesday, and Los Angeles (my favorite). In “Cast of Thousands” the speaker takes us to war, explaining how “They buried my village a house at a time, / unable to sort a body holding from a body held,” and when we turn the page, it is the World War’s turn to speak.

The gifting of books is a dangerous practice and an art I aspire to master. I’ve given novels and children’s literature and even coloring books, each one with a few thought-out lines on why it was chosen for that particular person. But recommending poetry? And to readers at large? That is a habit I have yet to adopt. Consider this my warm-up lap.

An Interview with Lydia Millet

I met Lydia Millet in 2009, in a writing workshop at the University of Alabama. I remember grabbing a beer and talking about graphic novels and Friday Night Lights at our local pub, about having children and a job and still finding time to write, and about how nice it was to get away for a weekend. I didn’t even know she liked animals — until I picked up the first book of a trilogy she’s currently working on.

I met Lydia Millet in 2009, in a writing workshop at the University of Alabama. I remember grabbing a beer and talking about graphic novels and Friday Night Lights at our local pub, about having children and a job and still finding time to write, and about how nice it was to get away for a weekend. I didn’t even know she liked animals — until I picked up the first book of a trilogy she’s currently working on.

Lydia Millet is the author of many novels as well as a story collection called Love in Infant Monkeys (2009), which was one of three fiction finalists for the Pulitzer Prize. 2011 saw the publication by W.W. Norton of a novel called Ghost Lights, named a New York Times Notable Book, as well as Millet’s first book for middle readers, called The Fires Beneath the Sea. Millet works as an editor and writer at a nonprofit in Tucson, Arizona, where she lives with her two small children.

* * *

Megan Paonessa: First off, how do you like being compared to Kurt Vonnegut on the cover of How the Dead Dream? I like Vonnegut, don’t get me wrong (he’s a Hoosier!), but that sort of blurb obviously colors expectations — and one can’t help but judge a book by its cover.

Lydia Millet: I’m always a bit perplexed by that comparison, owing to the fact that I haven’t read Vonnegut since my teens. Clearly I need some reeducation. In general though, comparisons to other writers are simultaneously flattering and insulting. I don’t know why it’s so necessary to go the Hollywood pitch route to describe literary books. “It’s Writer Brand X crossed with Writer Brand Y.” If I’m doing my job it’s not X crossed with Y at all.

MP: How do you feel about stereotypes? The IRS man. The real estate man. The office affair. The gay Air Force man. The breast-obsessed business types. These are all stereotypical character traits found in your novels, but as I found myself identifying them, I still thought these characters were uniquely interesting.

LM: I love stereotypes — types in general. I’m guessing that’s pretty clear. They are fascinating. Hey, stereotypes don’t kill people. Bad writing kills people.

MP: True! I guess what I’m trying to ask is, do you use stereotypes in order to say something . . . broader (?) . . . about life, the world, people? You mentioned in an interview with Willow Springs that one of the things you react against is the preoccupation with the personal in contemporary literary fiction.

LM: Well stereotypes are mostly just obvious objectifications of people, right? Partly I want to objectify fictional people because it’s funny; partly I want to objectify them because I like to play with distance — the distance between the reader and the characters, the narrator and the characters, the author and the characters.

MP: Many of your reviewers describe your writing as deeply satirical. How important to you is the insertion of a political / ecological / moral / social stance?

LM: All this talk of insertion! It sounds rude. I don’t think of inserting things.

Not all my writing has a satirical tone. The trilogy of novels doesn’t, for example. But I can never leave the comic aside for too long.

MP: What do you mean by the comic?

LM: The comedic. I always end up returning to what’s funny to me, whether it’s marginal in a book or central. So while I don’t know that my most recently published books are particularly satirical, I do have a book I’m working on that’s more so, if only because I need to get away from the heavy sometimes.

MP: Writing drama carries the hazard of falling into melodrama — as Hal points out at the end of Ghost Lights. From what I’ve read about your work, Hal’s sort of soul pouring wasn’t always common in your characters. Was this trait specific to Hal, or has your writing been influenced in a new direction?

LM: Well, I don’t know that it’s not common — I’ve always been a sucker for internal monologue and so I think there’s a fair amount of soul pouring throughout my books. Ghost Lights is less a new direction than How the Dead Dream was.

MP: Do you think there’s a move in contemporary literary fiction to steer clear of emotional narratives?

LM: I think the pretense that writing without emotion can exist is funny. You don’t want to go the direction of maudlin, you don’t want to overwrite, but underwriting emotion is a bore too, finally — safe and easy.

MP: So there has to be a balance.

LM: I wouldn’t say balance. Balance implies equilibrium, and I’m not sure how helpful that is in fiction. But I’d say emotion and cerebration are both important and compelling, and either without the other is a bit dull to me.

MP: Lastly, can you give us a glimpse into the last book of the trilogy? Perhaps (!!) which character’s point of view the narration will come through?

LM: My pleasure! The last book will come out next fall from Norton, it’s called Magnificence, and it’s written from the perspective of Susan, Hal’s wife. She inherits a house full of taxidermy in Pasadena.

MP: Taxidermy? Fantastic. I wonder how T. will react to that. I can’t wait to read it! Thanks, Lydia.